About Chapter 1: Acids and Bases Notes – Class 10 Chemistry

Acids and bases form the foundation of Chemistry at the Class 10 level, as they are used in everyday life, industries, laboratories, and nature. Acids are substances that produce hydrogen ions in aqueous solution, while bases release hydroxide ions. The study of their properties, reactions, and uses makes this chapter highly significant for board exams and competitive preparation. Acids are categorised as strong acids like hydrochloric acid and sulphuric acid, and weak acids like acetic acid and carbonic acid. Their strength depends on the extent of ionisation in water. Bases are also classified into strong bases, such as sodium hydroxide and potassium hydroxide, and weak bases like ammonium hydroxide. Indicators such as litmus, phenolphthalein, and methyl orange are commonly used to distinguish between acids and bases. One must go through the NCERT textbook for class 10 and solve the questions with the help of the NCERT solutions for class 10 science.

The chemical properties of acids include their reaction with metals producing hydrogen gas, with bases forming salt and water neutralisation, and with carbonates releasing carbon dioxide. Bases, on the other hand, react with oils and fats to form soap in a process called saponification. Neutralisation reaction between acid and base is an essential concept, as it helps explain the maintenance of pH balance in the human body, soil, and environment. The pH scale ranges from 0 to 14, where values less than 7 indicate acidic solutions, greater than 7 indicate basic solutions, and 7 represents neutral substances. The importance of pH can be seen in agriculture (soil treatment with lime to reduce acidity), medicine (antacids to relieve acidity), and daily life (shampoos and detergents designed for suitable pH levels). Natural indicators such as turmeric and red cabbage juice change colour depending on acidity or basicity, making them effective alternatives to chemical indicators. Industrial uses of acids include the manufacture of fertilisers, explosives, and dyes, while bases are used in soap, detergent, and paper industries.

Environmental concerns also connect to this topic, with acid rain caused by oxides of sulphur and nitrogen lowering the pH of soil and water bodies, affecting aquatic life and vegetation. Proper control of industrial emissions is necessary to reduce their harmful effects. In summary, the chapter Acids and Bases develops conceptual clarity about chemical behaviour, reactions, pH significance, industrial applications, and environmental impact, making it a vital topic for board preparation.

What Are Acids?

Acids are substances that release hydrogen ions (H⁺) when dissolved in aqueous solution. The sour taste of lemon juice, vinegar, and spoiled milk results from their acidic nature. According to the modern definition, an acid is characterized by its ability to donate protons (H⁺ ions) in water.

Acids are classified into two main categories based on their source:

Mineral Acids are derived from rocks and minerals. Examples include hydrochloric acid (HCl), sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄), and nitric acid (HNO₃). These acids find extensive use in industrial applications, from manufacturing fertilizers to petroleum refining.

Organic Acids occur naturally in plants and animals. Acetic acid in vinegar, citric acid in citrus fruits, and lactic acid in curd are common examples. These acids typically have weaker acidic properties compared to mineral acids.

Physical and Chemical Properties of Acids

Acids exhibit distinctive physical properties: they turn blue litmus paper red, change methyl orange to pink, and keep phenolphthalein colorless. Their aqueous solutions conduct electricity due to the presence of ions, and most possess corrosive properties that can damage skin and other materials.

The chemical behavior of acids becomes evident through several characteristic reactions. When acids react with metals, they produce salts and hydrogen gas a displacement reaction where more active metals displace hydrogen from the acid. For instance, zinc reacting with dilute sulfuric acid produces zinc sulfate and hydrogen gas, which burns with a characteristic "pop" sound.

Understanding Bases and Their Properties

Bases are substances that release hydroxide ions (OH⁻) in aqueous solution. They typically have a bitter taste and slippery, soapy feel. Water-soluble bases are specifically called alkalies, such as sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and potassium hydroxide (KOH).

Bases demonstrate opposite indicator behaviors to acids: they turn red litmus paper blue, change methyl orange to yellow, and turn phenolphthalein pink. Like acids, base solutions conduct electricity due to ionic dissociation.

Acid Strength and Ionization

The strength of an acid depends on its degree of ionization in water.

- Strong acids like HCl, HNO₃, and H₂SO₄ ionize completely, producing large concentrations of H⁺ ions.

- Weak acids such as acetic acid (CH₃COOH) and carbonic acid (H₂CO₃) only partially ionize, resulting in lower H⁺ concentrations.

This distinction is crucial: higher H⁺ concentration corresponds to greater acidic strength. Diluting an acid decreases its H⁺ concentration and reduces its strength—a principle important for safe laboratory practices.

The pH Scale: Measuring Acidity and Basicity

The pH scale provides a quantitative measure of hydrogen ion concentration in solutions. Developed by S.P.L. Sorensen, pH stands for "power of hydrogen" and ranges from 0 to 14.

The mathematical definition of pH is:

pH = -log[H⁺] or pH = -log[H₃O⁺]

This logarithmic scale means:

- pH < 7: Acidic solution

- pH = 7: Neutral solution (pure water)

- pH 7: Basic/alkaline solution

Each pH unit represents a tenfold change in hydrogen ion concentration. A solution with pH 3 is 1,000 times more acidic than one with pH 6. This logarithmic relationship makes the pH scale particularly useful for expressing the wide range of acidity and basicity found in everyday substances.

pH in Daily Life

The pH concept has practical significance across multiple domains. Human blood maintains a narrow pH range of 7.36-7.42, regulated by bicarbonates and carbonic acid acting as buffers. Gastric juice in the stomach has pH 1.0-3.0, enabling food digestion while potentially causing discomfort when produced in excess.

Tooth enamel, composed of calcium phosphate, remains stable at normal pH but corrodes when mouth pH drops below 5.5 typically due to bacterial acid production from sugar. This explains why dentists recommend limiting sugary foods and using basic toothpastes to neutralize acid.

Neutralization Reactions

Neutralization occurs when an acid reacts with a base to produce salt and water:

Acid + Base → Salt + Water

At the ionic level, this represents the combination of hydrogen ions from the acid with hydroxide ions from the base:

H⁺(aq) + OH⁻(aq) → H₂O(l)

These reactions are exothermic, releasing approximately 57.1 kJ of energy when strong acids react with strong bases. Neutralization has practical applications from treating acid indigestion with antacids to neutralizing insect stings.

Important Chemical Compounds

Sodium Chloride (Common Salt)

Sodium chloride (NaCl) serves as a fundamental compound beyond its culinary uses. Extracted from seawater through evaporation or mined as rock salt from underground deposits, it functions as the starting material for numerous chemicals including sodium hydroxide, washing soda, and baking soda.

Sodium Carbonate (Washing Soda)

Washing soda (Na₂CO₃·10H₂O) is manufactured through the Solvay process, starting with sodium chloride. The decahydrate form contains ten water molecules of crystallization. Upon air exposure, it effloresces, losing nine water molecules to form the monohydrate (Na₂CO₃ H₂O).

This compound finds use in glass manufacturing, water softening, and as a cleaning agent due to its basic properties.

Sodium Hydrogen Carbonate (Baking Soda)

Baking soda (NaHCO₃) is produced in the Solvay process by reacting sodium chloride with ammonia and carbon dioxide. When heated, it decomposes to form sodium carbonate, water, and carbon dioxide:

2NaHCO₃→ Na₂CO₃ + H₂O + CO₂

This carbon dioxide release makes baking soda essential in baking powder, where it causes dough to rise. It also serves as an antacid, neutralizing excess stomach acid.

Calcium Oxychloride (Bleaching Powder)

Bleaching powder (CaOCl₂) is prepared by passing chlorine gas over slaked lime at 313 K. Its bleaching action results from chlorine release. Applications include textile and paper bleaching, water disinfection, and chloroform manufacture.

Calcium Sulfate (Gypsum and Plaster of Paris)

Gypsum (CaSO₄ 2H₂O) contains two water molecules of crystallization. When heated to 373 K, it loses 1.5 water molecules to form Plaster of Paris (CaSO₄ 1/2 H₂O):

CaSO₄·2H₂O → CaSO₄ ½ H₂O + 1½H₂O

Plaster of Paris, when mixed with water, sets into a hard mass by rehydrating back to gypsum. This property makes it invaluable for medical casts, sculptural molds, and construction applications.

Formulas Reference Table

| Formula Name | Mathematical Expression | Explanation |

| pH Definition | pH = -log [H+] | Measures hydrogen ion concentration on logarithmic scale |

| Alternate pH | pH = -log[H3O+] | Equivalent expression using hydronium ion |

| Water Ionization | [H+][OH-] =10-4 at 298K | Ion product of water at standard temperature |

| Neutralization (Ionic) | H+(aq) + OH-(aq) → H2O(l) | Essential reaction between acid and base |

| Acid-Metal Reaction | Metal + Acid → Salt + H2 | General displacement reaction pattern |

| Acid-Carbonate Reaction | Carbonate + Acid → Salt + H2O + CO2 | Produces characteristic carbon dioxide gas |

| Gypsum Dehydration | CaSO4 . 2H2O → CaSO4 1/2 H2O + 1 1/2 H2O | Converts gypsum to Plaster of Paris |

| Baking Soda Decomposition | 2NaHCO3 → Na2CO3 + H2O + CO2 | Thermal decomposition releasing CO2 |

Indicators: Detecting Acids and Bases

Chemical indicators change color in response to pH changes, making them essential tools for identifying acidic or basic solutions.

- Litmus (extracted from lichens) turns red in acids and blue in bases.

- Phenolphthalein remains colorless in acids but turns pink in bases.

- Methyl orange appears pink in acids and yellow in bases.

- Universal indicators contain multiple dyes that produce different colors across the entire pH range (0-14), allowing quantitative pH determination through color comparison.

- Olfactory indicators represent an interesting category that distinguishes acids from bases through smell changes. Onion and vanilla extracts maintain their odor in acidic solutions but lose it in basic solutions, demonstrating the chemical interaction between bases and aromatic compounds.

Safe Handling and Dilution

Acid dilution requires careful technique due to the highly exothermic nature of the process. The cardinal rule: always add acid to water, never water to acid. Adding water to concentrated acid can cause violent boiling and splashing due to rapid heat generation, potentially causing severe burns.

When properly diluted by adding acid slowly to water with stirring, the heat dissipates safely into the larger water volume, preventing dangerous temperature spikes.

This comprehensive understanding of acids, bases, and salts forms the foundation for advanced chemistry studies and practical applications in industry, medicine, and everyday life. The concepts presented here from pH measurement to neutralization reactions demonstrate the systematic, predictable nature of chemical behavior governed by well-established principles.

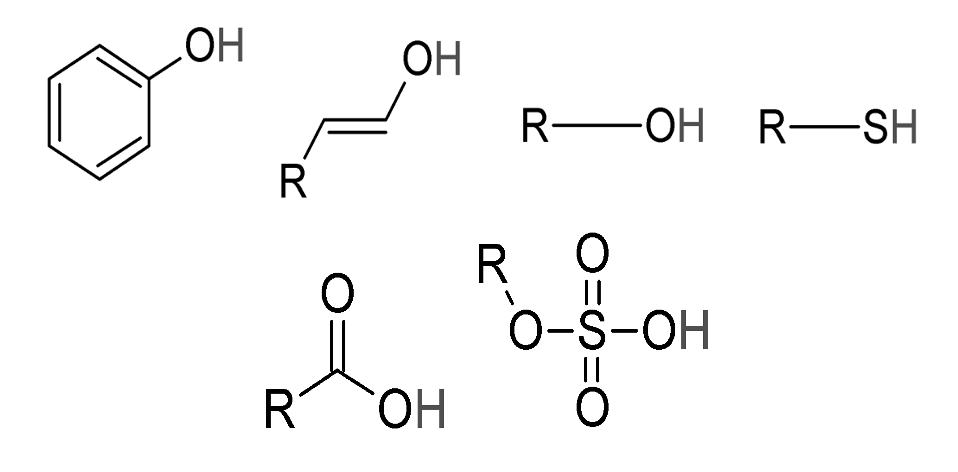

Acids

Substances with sour taste are regarded as acids. Lemon juice, vinegar, grape fruit juice and spoilt milk etc. taste sour since they are acidic. Many substances can be identified as acids based on their taste but some of the acids like Sulphuric acid have very strong action on the skin which means that they are corrosive in nature. In such cases it would be according to modern definition

An acid may be defined as a substance which releases one or more H+ ions in aqueous solution.

Acids are mostly obtained from natural sources. On the basis of their source acids are of two types

(a) Mineral acids

(b) Organic acids

Mineral Acids:

Acids which are obtained from rocks and minerals are called mineral acids.

Organic Acids:

Acids which are present in animals and plants are known as organic acids. A list of commonly used acids along with their chemical formula and typical uses, is given below

| Name | Type | Chemical Formula | Where found or used |

| Carbonic acid | Mineral acid | H2CO3 | In soft drinks and lends fizz, In stomach as gastric juice, used in tanning industry |

| Nitric acid | Mineral acid | HNO3 | Used in the manufacture of explosives (TNT, Nitroglycerine) and fertilizers (Ammonium nitrate, Calcium nitrate, Purification of Au, Ag. |

| Hydrochloric acid | Mineral acid | HCl | In purification of common salt, in textile industry as bleaching agent, to make aqua regia. |

| Sulphuric acid | Mineral acid | H2SO4 | Commonly used in car batteries, in the manufacture of fertilizers (Ammonium sulphate, super phosphate) detergents etc, in paints, plastics, drugs, in manufacture of artificial silk, in petroleum refining. |

| Phosphoric acid | Mineral acid | H3PO4 | Used in antirust paints and in fertilizers. |

| Formic acid | Organic acid | HCOOH(CH2O2) | Found in the stings of ants and bees, used in tanning leather, in medicines for treating gout. |

| Acetic acid | Organic acid | CH3COOH(C2H4O2) | Found in vinegar, used as solvent in the manufacture of dyes and perfumes. |

| Lactic acid | Organic acid | CH3CH(OH)COOH(C3H6O3) | Responsible for souring of milk in curd. |

| Benzoic acid | Organic acid | C6H5COOH | Used as a food preservative. |

| Citric acid | Organic acid | C7H6O2 | Present in lemons, oranges and citrus fruits. |

Physical Propeties of Acids

(i) Sour taste: Almost all acidic substances have a sour taste.

(ii) Action on litmus solution: Acids turn blue litmus solution red.

(iii) Action on methyl orange: Acids turn methyl orange pink.

(iv) Action on phenolphthalein: Phenolphthalein remains colourless in acid.

(v) Conduction of electricity: The aqueous solution of acid conducts electricity.

(vi) Corrosive nature: Most acids are corrosive in nature. They produce a burning sensation on the skin and make holes on surfaces on which they fall.

Chemical Properties of Acids

Reaction of Acids with Metals:

When acid reacts with a metal, then a salt and hydrogen gas are formed.

i.e. Metal + Acid → Salt + Hydrogen gas

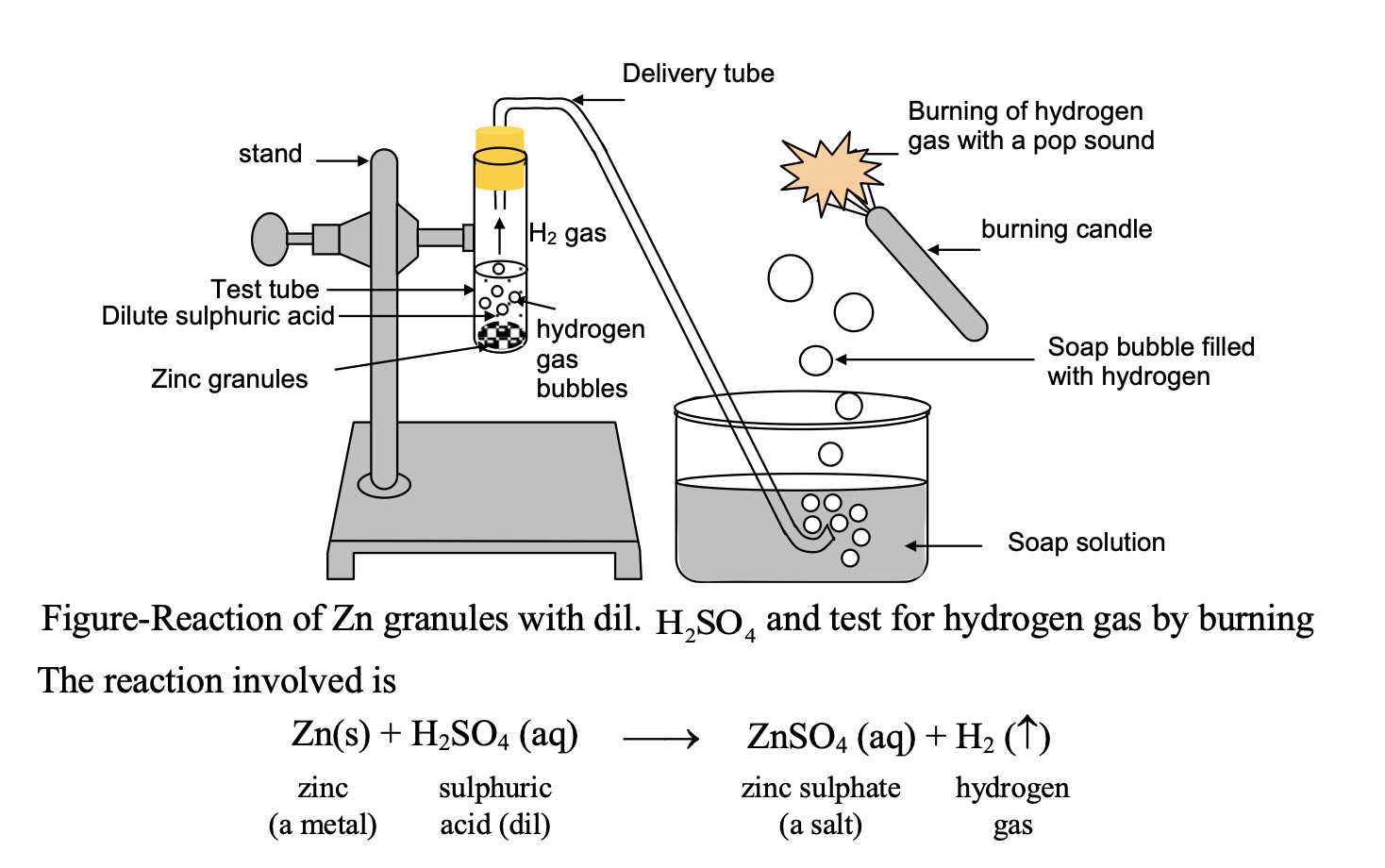

⇒ Reaction of dil with zinc metal.

Experiment: Take about 5 ml of dil H2SO4 in a test tube and add a few pieces of zinc granules in it. Pass the gas evolved through soap solution. The soap bubbles filled with gas rise.

Test for gas: Bring a burning candle near the gas filled soap bubble.

Observation: The gas present in soap bubble burns with pop sound which shows the gas evolved during reaction is hydrogen gas.

In this reaction more active metal zinc displaces less active hydrogen from H2SO4 and this hydrogen is evolved as gas.

Thus it is an example of displacement reaction. Some more examples of reaction of different metals with a particular acid:

Ex.:

Mg(s) + 2HCl(aq) → MgCl2(aq) + H2(g)

Magnesium + hydrochloric acid → magnesium chloride + hydrogen

(a metal) + (dil) → (a salt) + gas

Ex.:

Zn(s) + 2HCl(aq) → ZnCl2(aq) + H2(g)

zinc + hydrochloric acid → zinc chloride + hydrogen

(a metal) + (dil)→ (a salt) + gas

Ex.:

Fe(s) + 2HCl(aq) → FeCl2(aq) + H2(g)

iron + hydrochloric acid → iron(II) chloride + hydrogen

(a metal) + (dil) → (a salt) + gas

Ex.:

Cu + 2HCl(aq)→ no reaction

copper + hydrochloric acid

(a metal) + (dil)

The order of reactivities of above metals with same acid (dil HCl) is Mg > Zn > Fe > Cu i.e. these metals do not react with same acid with same vigour.

It is observed that at room temperature

(i) Mg reacts most vigorously

(ii) Zn reacts less vigorously than Mg

(iii) Fe reacts slowly

(iv) Cu does not react at all

Conclusion: From above reactions we reach to a conclusion that all metals do not react with same acid with same vigour.

The reason is the different reactivities or activities of metals towards acid.

In the above reactions we observe that metals like Mg, Fe, Zn being more active than hydrogen, displaces hydrogen from acid HCl and release H2 gas. Thus above reactions are displacement reactions, Cu being less reactive than hydrogen, cannot displace hydrogen from dil HCl. Thus no reaction takes place.

REACTION OF ACID WITH METAL CARBONATES AND METAL HYDROGEN CARBONATE (OR METAL BICARBONATES):

When an acid reacts with a metal carbonate or metal hydrogen carbonate (metal bicarbonate), then a salt, CO2 gas and H2O are formed.

i.e. Metal carbonate + Acid → Metal Salt + CO2 + H2O

Metal hydrogen carbonate (or metal bicarbonate) + Acid → Metal Salt + CO2 + H2O

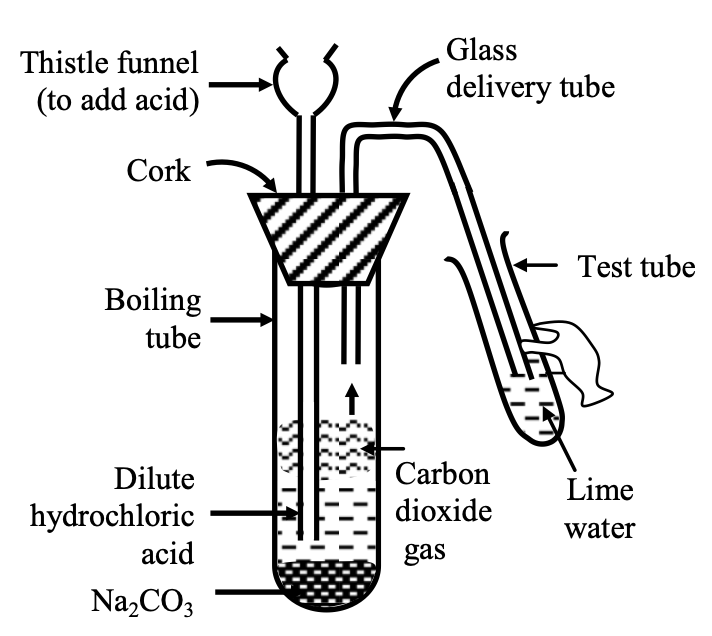

⇒ Reaction of sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) or sodium hydrogen carbonate (NaHCO3) with dil HCl.

Experiment: Take about 0.5g of Na2CO3 or NaHCO3 in a test tube and add about 2 ml of dil HCl acid to it. Pass the gas evolved through lime water (taken in another test tube).

Observation: The lime water turns milky, showing that the gas evolved is CO2 gas.

Figure-Carbon dioxide gas (formed by the action of dil. HCl and Na2CO3) being passed through lime water

The reactions taking place are

Na2CO3(s) + 2HCl(aq) → 2NaCl(aq) + H2O(l) + CO2(g)

sodium carbonate hydrochloric acid sodium chloride water carbondioxide

(dil) (a salt)

Ca(OH2) (aq) + CO2(g) → CaCO3(s) + H2O(l)

lime water carbondioxide calcium carbonate water

(white ppt) (milky suspension)

Note:

(i) The lime water on passing CO2 gas turns milky due to formation of white ppt. of CaCO3 (insoluble in water) having milky appearance.

(ii) On passing excess of CO2 gas through lime water, milkiness disappears due to dissolution of white ppt of CaCO3 and clear solution is formed due to formation of soluble calcium bicarbonate [Ca(HCO3)2]

CaCO3(s) + H2O(l) + CO2(g) → Ca(HCO3)2(aq)

calcium carbonte water carbondioxide calcium bicarbonate

(white ppt)

(soluble in water) (insoluble in water) colourless

Ex.: MgCO3 (s) + 2HCl (aq) → MgCl2 (aq) + H2O (l) + CO2

(dil)

Mg(HCO3)2 (aq) + 2HCl (aq) → MgCl2 (aq) + 2H2O (l) + 2CO2

(dil)

Ex.: CaCO3 (s) + H2SO4(aq) → CaSO4(aq) + H2O (l) + CO2(g)

(dil)

Ca(HCO3)2(aq) + H2SO4(aq) → CaSO4(aq) + 2 H2O (l) + 2CO2(g)

(dil)

Ex.: ZnCO3 (s) + 2HCl (aq) → ZnCl2(aq) + H2O (l) + CO2(g)

(dil)

Zn(HCO3)2 (aq) + 2HCl(aq)→ ZnCl2(aq) + 2H2O (l) + 2CO2(g)

(dil)

REACTION OF ACIDS WITH BASES (NEUTRALIZATION REACTION)

When an acid reacts with a base then a salt and water are formed, i.e

Acid + Base → Salt + water

This reaction is called neutralization reaction, because when acid and base react with each other, they neutralize each other’s effect (i.e base destroys the acidic property of acid and acid destroys the basic property of base).

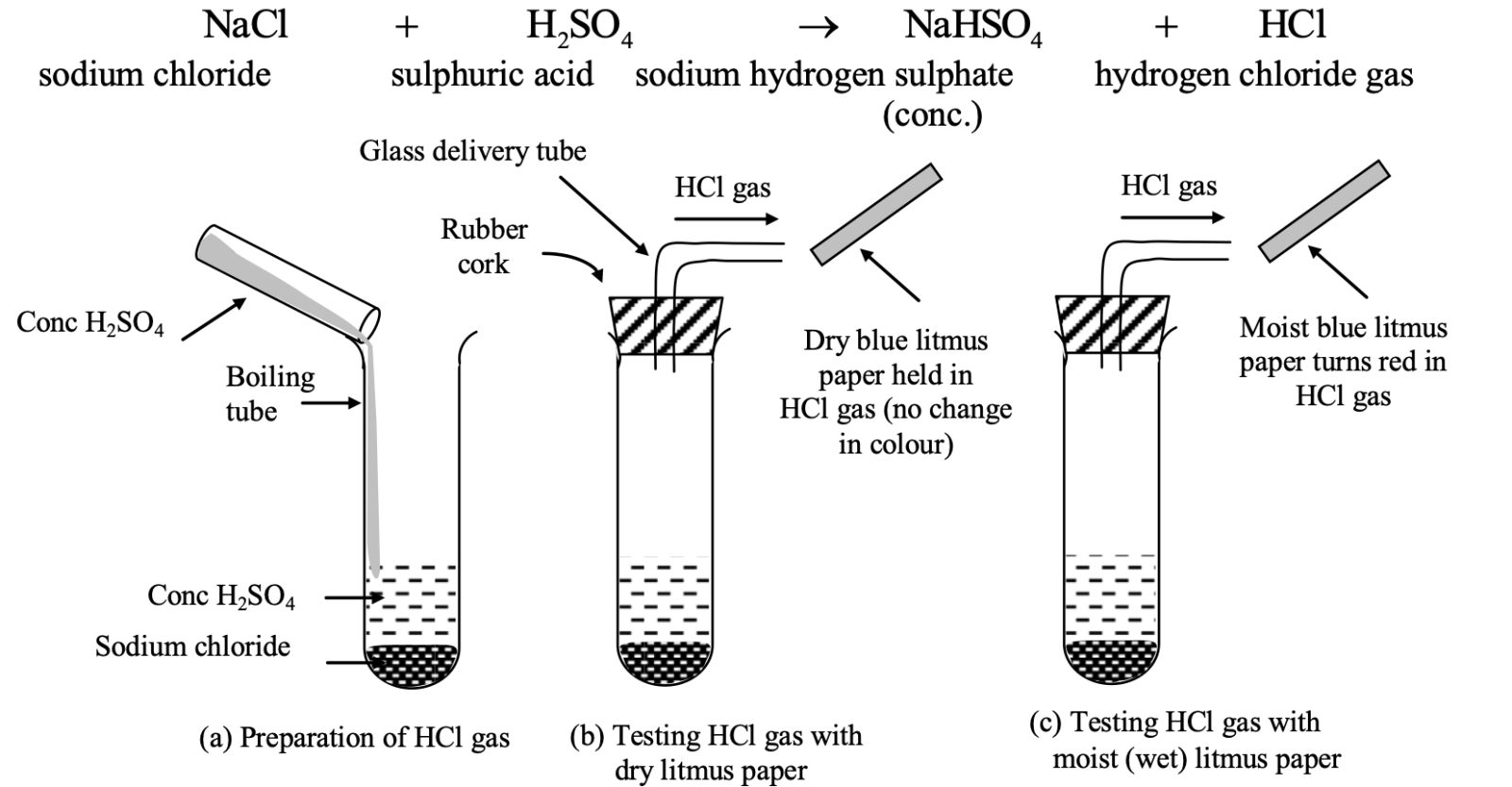

⇒ Reaction of hydrochloric acid (HCl) with sodium hydroxide (NaOH).

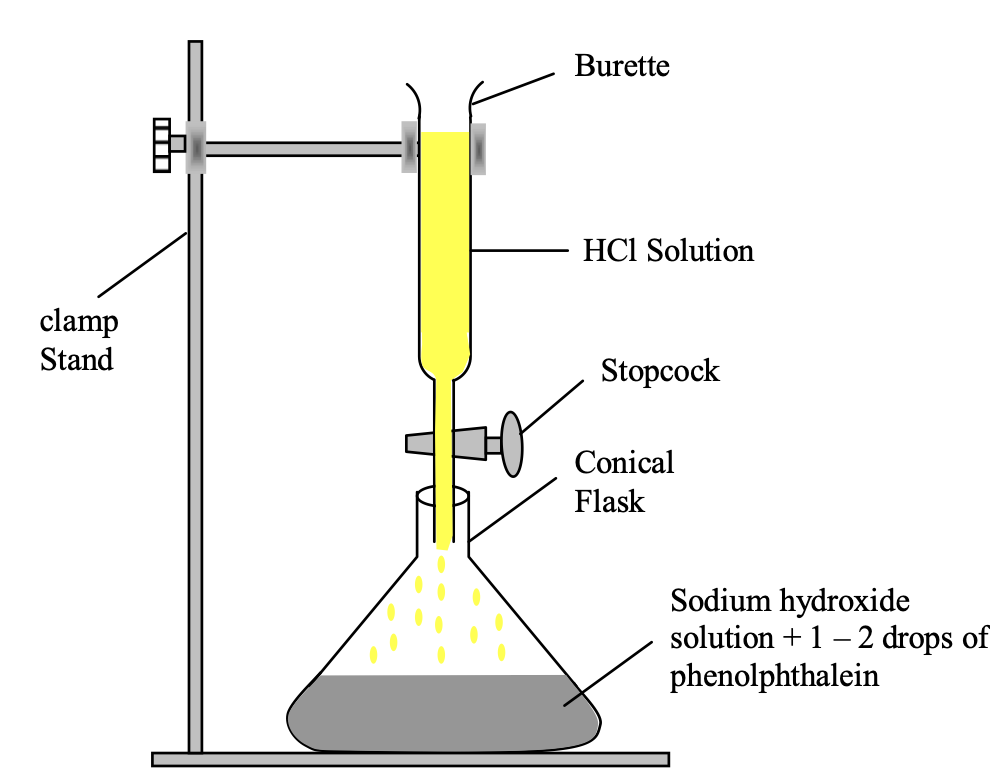

Experiment: Take about 10 ml of dil NaOH solution in a conical flask and add 2-3 drops of phenolphthalein indicator to it. The solution will turn pink (showing that it is basic in nature). Now add dil HCl solution from burette into flask slowly till the pink colour in the solution disappears.

Observation: This point (at which pink colour disappear) is called end point.

At end point:

(i) The dil NaOH solution in flask has been completely neutralised by dil HCl solution added from burette, dil NaOH has completely reacted with dil HCl.

(ii) [H+] = [OH–] (in case of NaOH & HCl)

(from acid) (from base)

The chemical reaction can be written as

NaOH (aq) + HCl (aq) → NaCl(aq) + H2O(l)

sodium hydroxide hydrochloric acid sodium chloride water

(base) (acid) (salt)

This reaction of acid and base to form salt and water is called neutralization reaction or neutralization of base by an acid

Figure-Neutralization of NaOH solution by HCl solution using phenolphthalein indicator

In the solution, NaOH, HCl and NaCl ionize completely into ions, so the above reaction can be written as:

Here's the text conversion with all mathematical symbols and expressions:

Na+ + OH- + H+ + Cl- → Na+ + Cl- + H2O

Canceling out the common ions on both sides, we get:

OH- + H+ →(neutralisation/Reaction)→ H2O

hydroxide ion hydrogen ion water (from base) (from acid)

Hence, neutralization may also be defined as the reaction between H+ ions given by acid with the OH- ions given by base to form water.

REACTION OF ACIDS WITH METALLIC OXIDES:

Acid react with metal oxide to form salt and water.

i.e. Metal oxide + Acid → Salt + Water

This reaction is similar to the neutralization reaction between acid and a base to form salt and water. Thus, the reaction between acids and metal oxides is a kind of neutralization reaction and shows that metallic oxides are basic oxides.

⇒ Reaction of copper (II) oxide with dilute hydrochloric acid:

Experiment: Take about 1- 2g of copper (II) oxide (black in colour) in a beaker. Add dil HCl slowly with constant stirring.

Observation: Black CuO dissolves in dil HCl and a bluish green solution is formed due to formation of copper (II) chloride (CuCl2) as salt.

The reaction taking place is:

Here is the text conversion of the chemical equation from the image:

CuO(s) + 2HCl(aq) → CuCl2(aq) + H2O

copper (II) oxide + hydrochloric acid → copper (II)chloride + water (black) (salt)

This represents a chemical reaction where solid copper (II) oxide reacts with aqueous hydrochloric acid to produce aqueous copper (II) chloride and water.

Note: In general Mineral Acids are Strong Acids while Organic Acids are Weak acids.

WHAT DO ALL ACIDS HAVE IN COMMON OR CHEMICAL NATURE OF ACIDS

⇒ To see what is common in all acids, let us perform the following experiment with different acids:

Experiment to illustrate chemical nature of acids or what do all acids have in common:

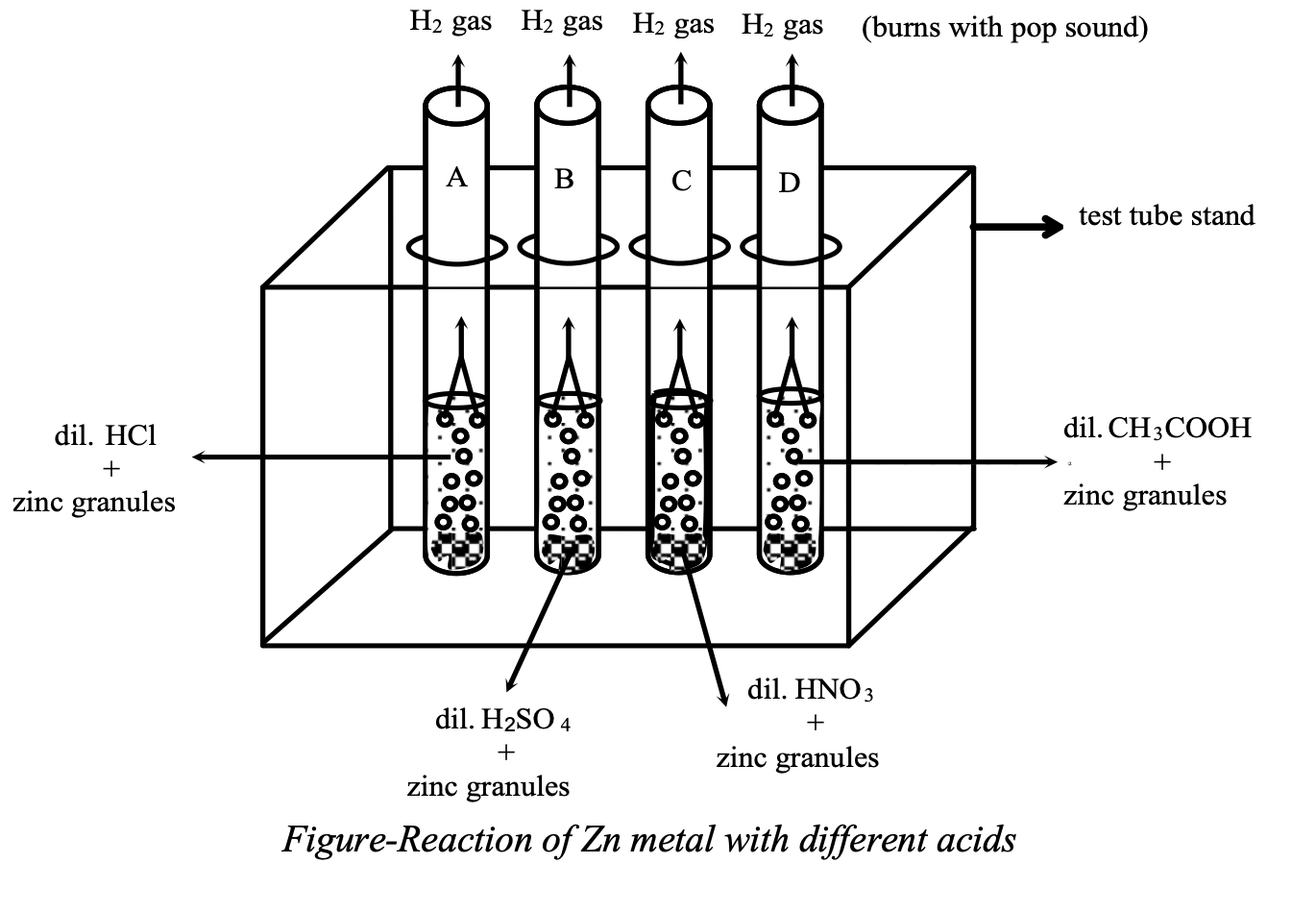

Take four test tubes and label them as A, B, C and D. Place them in a test tube stand. Take about 2 ml of each dil HCl, dil , dil and dil CH3COOH in test tubes A, B, C and D respectively. Now add few pieces of zinc granules in each test tube.

Observation: There is evolution of hydrogen gas (H2) in each test tube which burns with a pop sound on bringing a burning candle near the mouth of tubes.

Conclusion: Hydrogen is common in all acids i.e. all acids contain hydrogen which they liberate when they react with active metals.

Thus we can say that acids are the substances which contain hydrogen ion, which they liberate when they react with active metals.

All acids contain hydrogen but all hydrogen containing compounds are not acids, for example, glucose (C6H12O6) and alcohol (C2H5OH) contain hydrogen but they are not acids.

It can be explained more clearly by following experiment.

Experimentto show that all compounds containing hydrogen are not acids: The experiment is based on the fact that acids conduct electricity through their aqueous solutions.

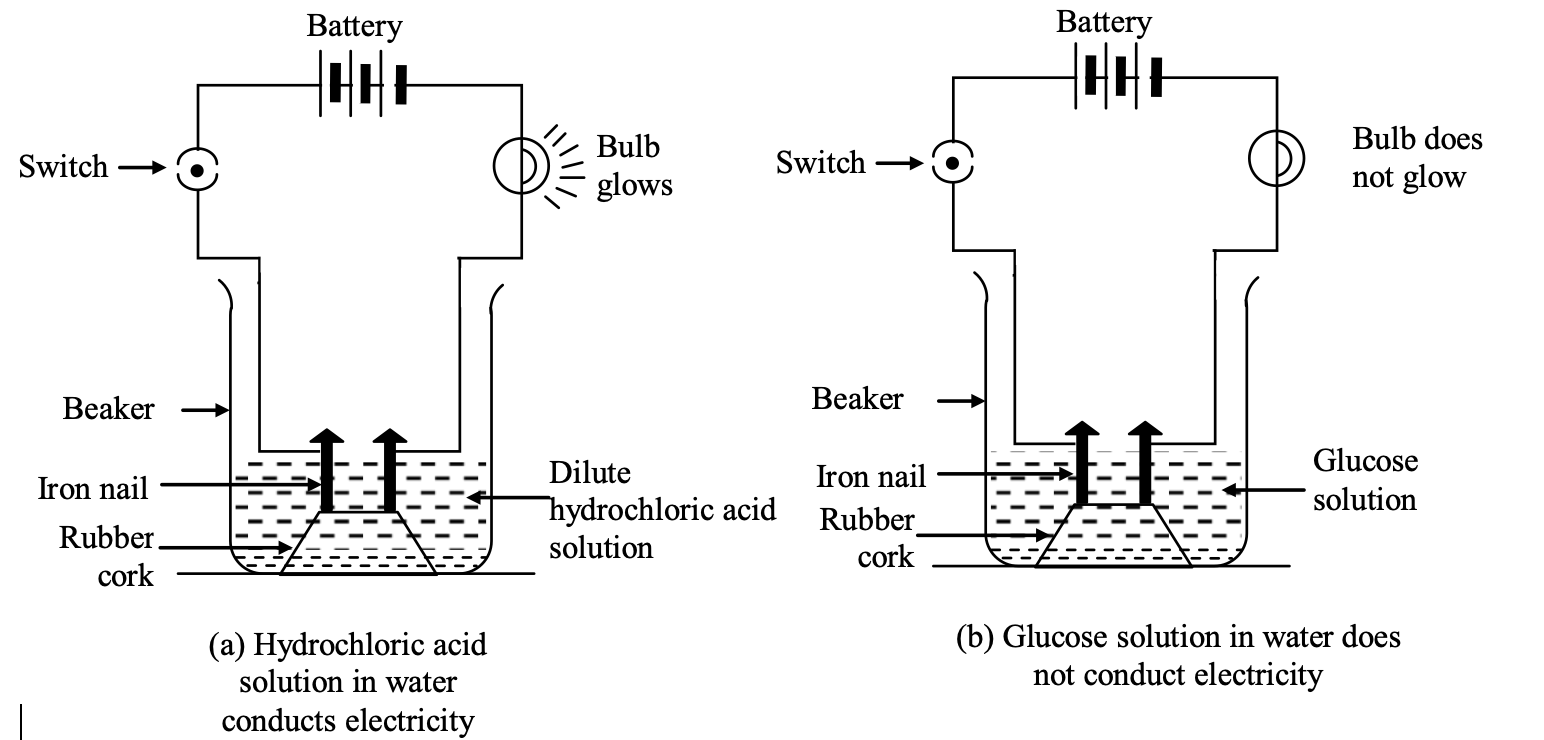

(i) Take aqueous solutions of hydrogen containing compounds like hydrochloric acid (HCl), sulphuric acid , glucose and alcohol in 4 beakers respectively.

(ii) Fix two iron nails on the rubber cork and place the cork in each beaker

(iii) Connect the nails to the two terminals of a 6 volt battery through a switch and a bulb in each beaker as shown in the following figures.

(iv) Switch on the current in each case

Observation:

(i) Bulb starts glowing in arrangements (a) and (c) containing aqueous solutions of HCl and acids respectively.

It shows aqueous solutions of hydrochloric acid (HCl) and sulphuric acid (H2SO4) conduct electricity.

(ii) Aqueous solutions of glucose (C6H12O6) and alcohol (C2H5OH) do not conduct electricity (i.e. they do not allow electricity to pass through them) as bulb does not glow in arrangements b and d containing aqueous solutions of glucose and alcohol.

Explanation: Conduction of electricity through the aqueous solutions of acids (HCl and H2SO4) is due to the ions present in them. For example, aqueous solution of H2SO4 contains H+ and SO2-4 ions. These ions can carry electric current and thus are responsible for conduction of electricity through HCl and H2SO4 solutions. On the other hand aqueous solutions of glucose and alcohol (hydrogen containing compounds) do not contain H+ ions or any other ions. Due to absence of ions, aqueous solutions of glucose and alcohol do not conduct electricity.

Conclusion: From the above experiment, we lead to a conclusion that only those hydrogen containing compounds are acidic which when dissolved in water give H+ ions in the solution. Thus the definition of acid is modified as:

Acids are the substances which contain hydrogen and which when dissolved in water give H+ ions in the solution. This is called Arrhenius definition of acids given by Arrhenius in 1884.

WHAT HAPPENS TO AN ACID IN WATER SOLUTION?

It is observed that acidic behaviour of acids is due to the presence of H+ ions in them, which they give only in presence of water. So in the absence of water, a substance will not form ions and hence will not show its acidic behavior. It can be explained more clearly by following experiments:

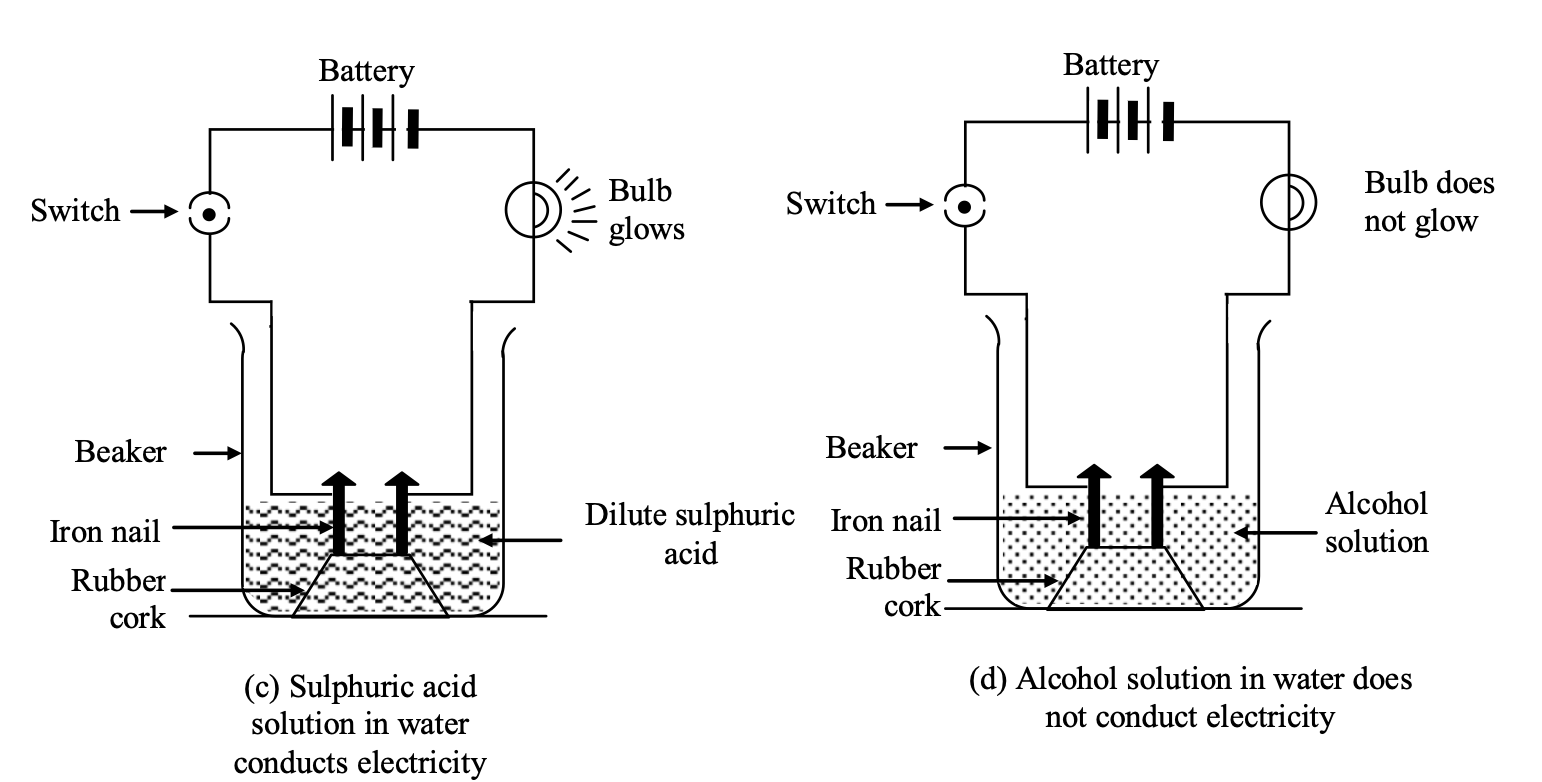

Experiment: Take about 1–2 g of NaCl in a dry test tube. Add some concentrated into the test tube. Following reaction takes place producing hydrogen chloride (HCl) gas

Now bring a dry blue litmus paper and a wet (or moist) blue litmus paper near the mouth of test tube (which contains HCl gas)

Observation:

(i) The dry litmus paper does not turn red. It shows that HCl gas does not behave as an acid in absence of water (since there is no water in dry litmus paper).

(ii) The wet (or moist) litmus paper turns red. It shows that HCl gas acts as an acid only in presence of water (which is present in moist or wet litmus paper).

Explanation:

(i) When HCl gas come in contact with dry litmus paper, then HCl does not dissociate into ions (i.e H+ and Cl⁻ ions) due to absence of water in dry litmus paper.

Since H+ ions are responsible for acidic behaviour of acids, HCl gas does not show acidic behaviour with dry litmus paper and thus it does not turn the blue litmus red (due to absence of H+ ion in dry HCl gas).

HCl(g) in absence of water → Dissociation does not occur. (acts as gas)

(ii) When HCl gas comes in contact with wet litmus paper, then HCl dissociates into H⁺ and Cl⁻ ions due to dissociation of HCl in water present in wet litmus paper.

Since H+ ions are responsible for acidic behaviour of acids, HCl gas shows acidic behaviour with wet litmus paper and thus it turns it into red (due to presence of H+ ions in wet HCl gas) i.e.

HCl(g) in presence of water→ H+(aq) + Cl-(aq)

(acts as acid) (dissociation occurs)

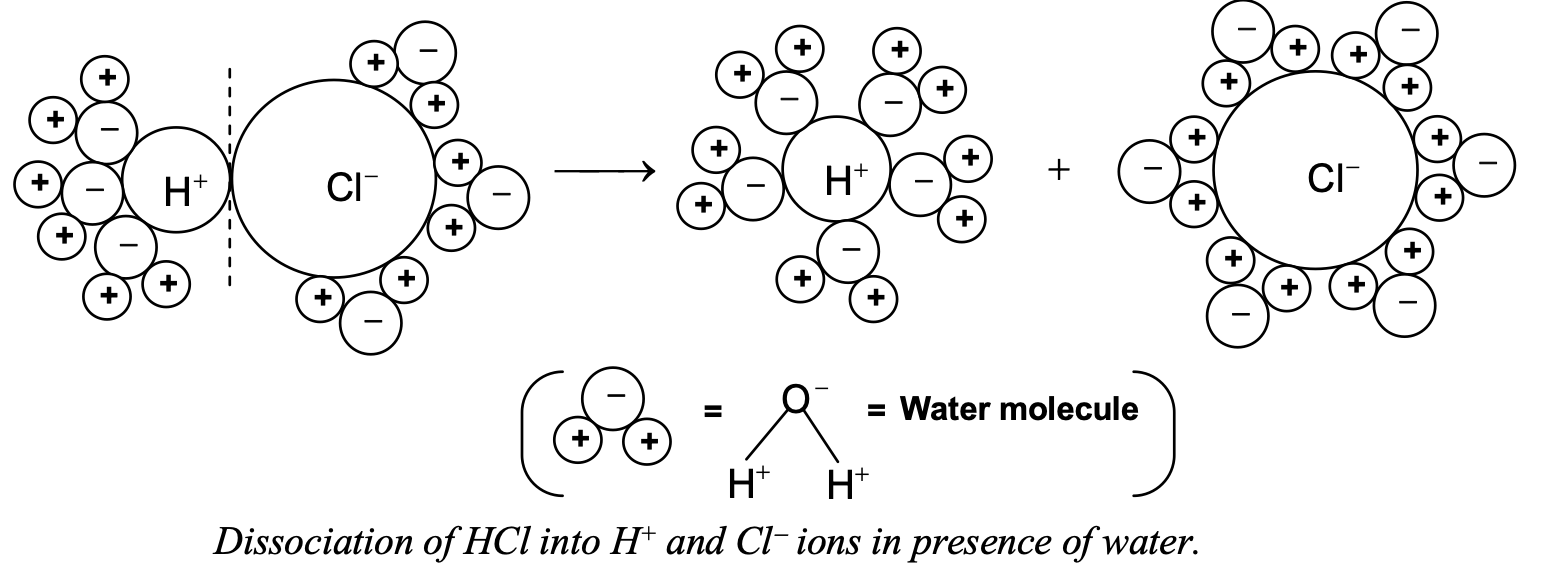

Such dissociation of a covalent molecule like HCl into ions in the presence of water is called ionization. The ionization of HCl is shown more clearly as follows:

It is clear from the figure that, after dissociation of HCl, a number of water molecules remain attached to H+ and Cl-. Hence they are represented as H+(aq) and Cl-(aq) (aq indicating water molecules)

Alternatively, H+ ions combine with water molecule to form an ion called hydronium ion.

H+ + H2O → H3O+

hydrogen ion water molecule hydronium ion

Thus H+ does not exist freely in water, but exist in combination with water molecules. Hence, we represent it as H+(aq) or H3O+.

Conclusion: The properties of an acid is due to H+(aq) ions or hydronium ions (H3O+) which it gives in the aqueous solution.

or

Acidic properties of acids are due to presence of H+(aq) ions or H3O+ ions which they produce only in presence of water.

or

In absence of water, a substance will not form H+(aq) ions or H3O+ ions and hence will not show its acidic behaviour.

Classification of Acids on the Basis of Degree of Ionization or Strenght of Acids on the basis of degree of ionization

The acids are classified into two categories on the basis of the degree of ionization as follows:

- Strong acids

- Weak acids

STRONG ACID:

An acid which is completely ionized in water and thus produces a large amount of H+(aq) ions is called a strong acid e.g. acids like hydrochloric acid (HCl), nitric acid (HNO3) and sulphuric acid (H2SO4) are completely ionized in water and thus produce large amounts of H⁺(aq)ions in the solution. So these are called strong acids. The ionization of these acids are represented as follows:

(i) HCl + water→ H+(aq) + Cl-(aq) hydrochloric acid hydrogen ion chloride ion

or

HCl (aq) → H+ (aq) + Cl- (aq)

(ii) HNO3 + water → H+ (aq) + NO-3 (aq) nitric acid hydrogen ion nitrate ion

or

HNO3 (aq) → H+ (aq) + No3- (aq)

(iii) H2SO4 + water → 2H+(aq) + SO2-4 (aq) sulphuric acid hydrogen ion sulphate ion

or

H2SO4 (aq) → 2H+ (aq) + SO42- (aq)

Characteristics of strong acids:

Due to large amounts of H+(aq) ions in the solutions of strong acids,

(i) They react rapidly with other substances (such as metals, metal carbonates and metal hydrogen carbonates or metal bicarbonates).

(ii) They have a high electrical conductivity.

(iii) They are strong electrolytes.

Weak Acids:

An acid which is partially ionized in water and thus produces small amount of H+(aq) ions is called a weak acid. e.g. Acids like Acetic acid (CH3COOH) Formic acid (HCOOH), Carbonic acid (H2CO3) and Phosphoric acid (H3PO4) etc, are partially ionised in water and thus produce small amounts of H⁺(aq) ions in the solution, so these are called weak acids. The ionization of these acids are represented as follows:

(i) CH3COOH + water ⇌ CH3COO-(aq) + H+(aq)

Acetic acid Acetate ion Hydrogen ion

or

CH3COOH(aq) ⇌ CH3COO⁻(aq) + H+(aq)

(ii) H2CO3 + water ⇌ 2H+(aq) + CO32-(aq)

Carbonic acid Hydrogen ion Carbonate ion

or

H2CO3 (aq) ⇌ 2H+(aq) + CO32-(aq)

(iii) H3PO4 + water ⇌ 3H+(aq) + PO43-(aq)

phosphoric acid hydrogen ion phosphate ion

or

H3PO4 (aq) ⇌ 3H+(aq) + PO43-(aq)

(iv) HCOOH + water ⇌ HCOO⁻(aq) + H+(aq)

formic acid formate ion hydrogen ion

or

HCOOH(aq) ⇌ HCOO⁻(aq) + H+(aq)

Characteristics of weak acids:

Due to small amounts of H+ (aq) ions in the solutions of weak acids,

(i) They react quite slowly with other substances (such as metals, metal carbonates and metal bicarbonates etc).

(ii) They have low electrical conductivity.

(iii) They are weak electrolytes.

Conclusion:

Greater the degree of ionization, greater is the amount of H+ (aq) ions produced in solution and stronger is the acid (or greater is strength of acid).

Smaller the degree of ionization, smaller is the amount of H+ (aq) ions produced in the solution and weaker is the acid (or lesser is the strength of acid).

Thus, strength of an acid is directly proportional to the degree of ionization.

Dilution of Concentrated Acids an Exothermic Reaction

Concentrated acid:

Pure acid is generally known as the concentrated acid.

Dilute acid:

A concentrated acid mixed with water is called a dilute acid and this process of mixing of water to a concentrated acid is called dilution.

Note: The dilution of an acid with water is an exothermic reaction i.e. on mixing water to an acid, heat is produced.

Experiment to verify that dilution of a concentrated acid is exothermic

Take a small amount of water in a beaker. Note its temperature. Now put a few drops of conc. H2SO4 or conc. HNO3 acid into it and note the temperature of beaker again.

Observation:

There is rise in temperature in each case.

Thus dilution of conc. acid is an exothermic reaction and is accompanied by ionization of acid as follows:

Chemical reactions:

Reaction 1:

H2SO4(l) + 2H2O → 2H3O+(aq) + SO42-(aq) + Heat

sulphuric acid (conc) water hydronium ion sulphate ion released

Reaction 2:

HNO3(l) + H2O(l) → H3O+(aq) + NO3-(aq) + Heat

nitric acid (conc.) water hydronium ion nitrate ion released

Conclusion:

From the above experiment we lead to a conclusion that dilution of concentrated acid in water is an exothermic (or heat releasing) reaction.

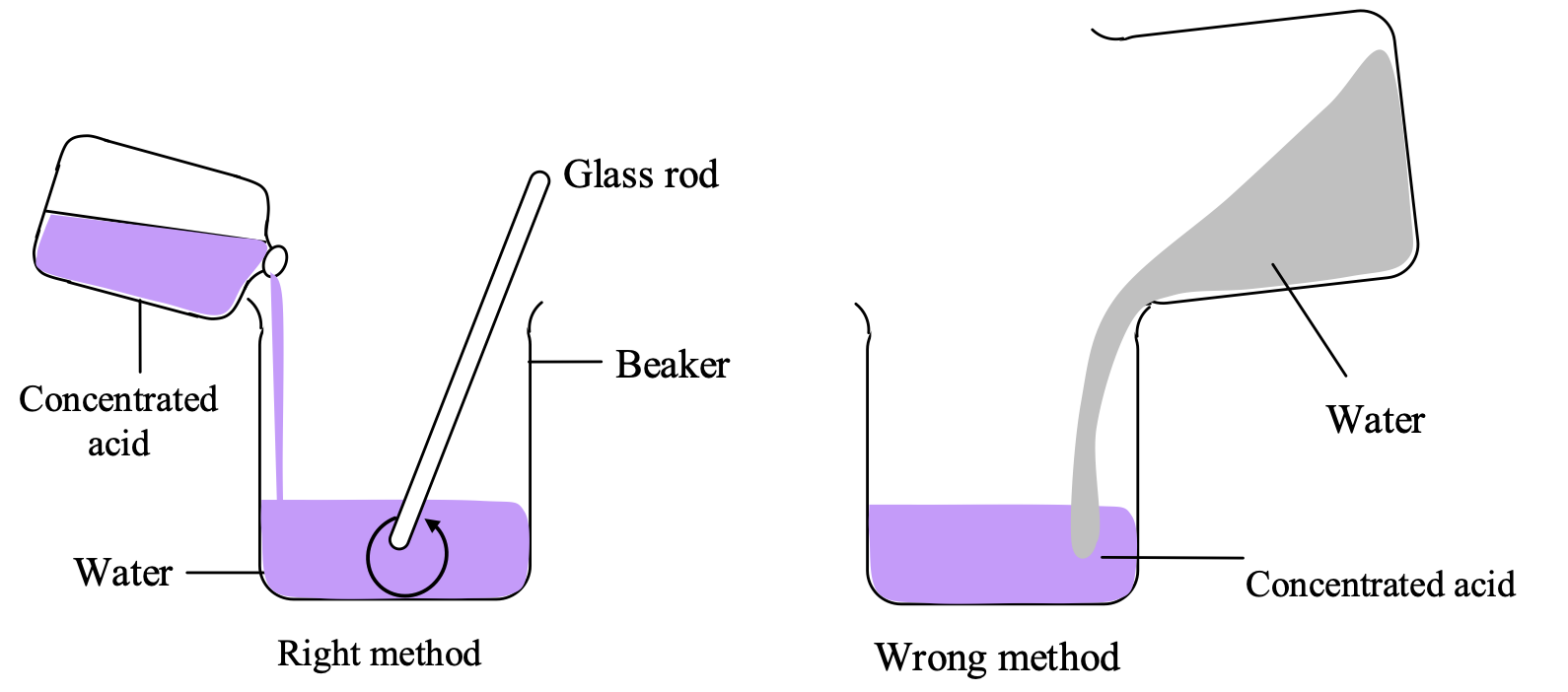

How to dilute a concentrated acid?

Since dilution of a concentrated acid is highly exothermic reaction, the heat produced is so large that the solution may splash out or glass beaker may break in which dilution is carried out due to excessive heating. Hence to slow down the exothermic process, dilution of a concentrated acid is always done by adding acid into water and not water into acid as shown in figure.

Conclusion:

We should dilute an acid by mixing acid into water and not water into acid.

Effect of dilution on [H+] of an acid:

On dilution, the [H+] in the solution decreases and the solution become less acidic (or strength of acid decreases). This can be verified by the following experiment

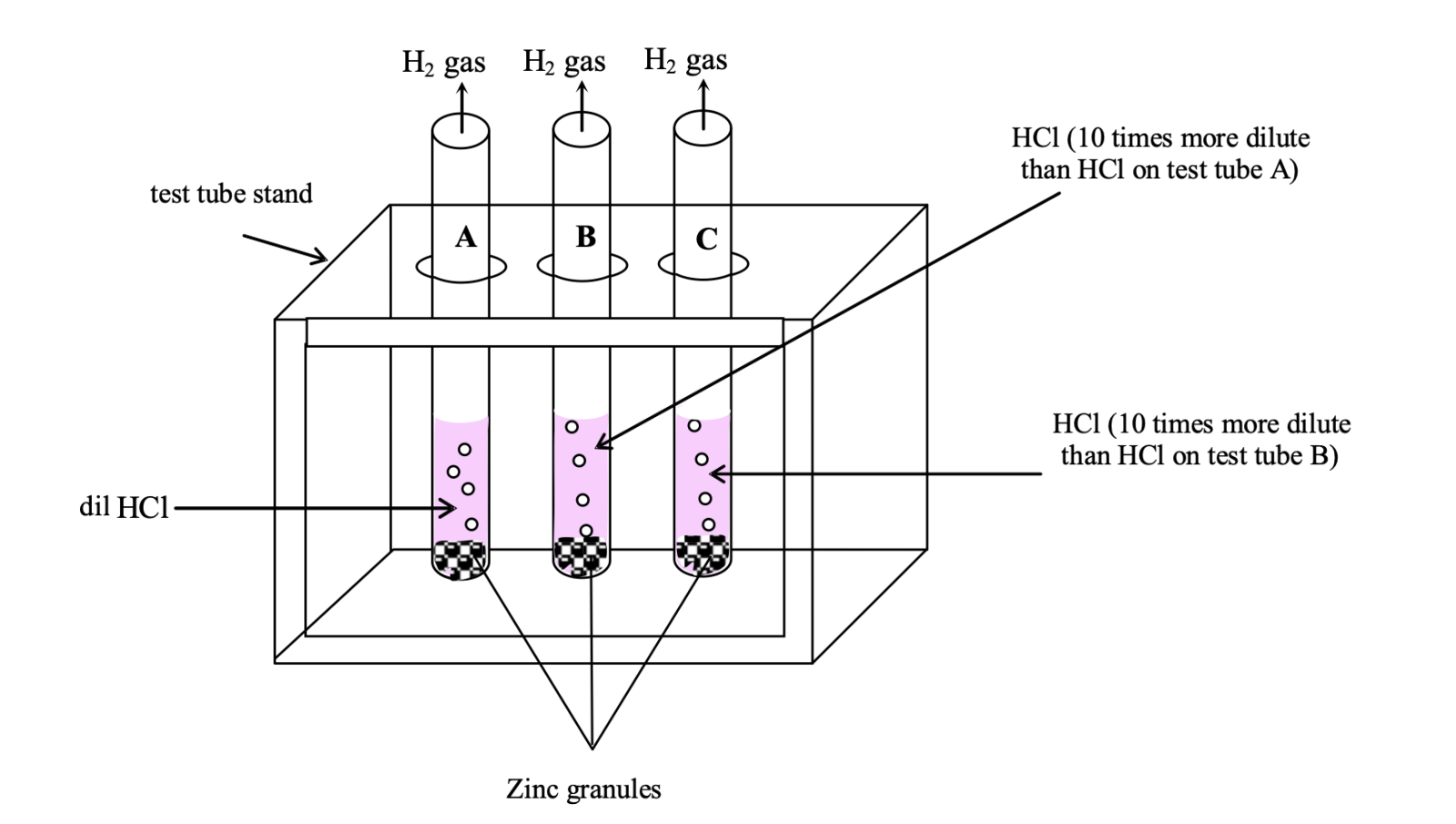

Experiment to verify that strength of an acid decreases on dilution

Take about 5 ml of dilute HCl acid in test tube A. In another test tube B, take 5 ml of more diluted HCl (10 times more dilute than HCl in test tube A). Similarly take about 5 ml of more diluted HCl (10 times more dilute than HCl in test tube B) in test tube C.

Now add few pieces of zinc granules in each of the test tubes.

Observation:

There is evolution of hydrogen (H2) gas in each case. According to the reaction:

Zn + 2HCl → ZnCl2 + H2(g)

zinc hydrochloric acid zinc chloride hydrogen

It is observed that the rate of evolution of H2 gas is fastest in test tube A (having small dilution) and lowest in test tube C (having large dilution) and moderate in test tube B.

Conclusion:

From the above experiment we lead to a conclusion that on dilution, [H+] in solution decreases. Thus acidic strength of an acid decreases on dilution (since strength of an acid is due to the presence of [H+] in solution).

Important Note: Acidic strength of an acid is affected by two factors:

(i) Degree of ionization of an acid:

i.e. strength of an acid ∝ degree of ionization

Greater the degree of ionization, greater will be [H+] in the solution and thus greater will be the strength of an acid (or stronger will be an acid). Similarly, smaller the degree of ionization smaller will be [H+] in solution and thus lesser will be the strength of an acid (or weaker will be the acid).

(ii) Dilution of an acid:

Strength of an acid is inversely proportional to the dilution of an acid, greater the dilution of an acid, greater the dilution of an acid, lesser will be [H+] in the solution and thus lesser will be the strength of an acid (or weaker will be the acid)

i.e strength of an acid ∝ 1/(dilution of an acid)

Similarly smaller the dilution of an acid, greater will be [H+] in solution and thus greater will be the strength of an acid (or stronger will be the acid).

MORE ABOUT ACIDS:

(i) Some naturally occurring acids: A few naturally occurring sources of acids and the acids present in them are given in table below:

| S. No. | Natural source | Acid Present |

| 1. | Oranges, lemons | Citric acid |

| 2. | Apples | Malic acid |

| 3. | Tomatoes | Oxalic acid |

| 4. | Tamarind (Imli) | Tartaric acid |

| 5. | Sour milk or curd | Lactic acid |

| 6. | Vinegar | Acetic acid |

| 7. | Proteins | Amino acids |

(ii) Handling acidic food stuff in the household : In traditional kitchens, copper and brass vessels are used even today. Hence, if curd or other sour substances which are acidic in nature are kept in these vessels, they react to form toxic compounds(since acids react with metals) and make the food stuff unfit for consumption.

Therefore, to protect them from such a reaction, these vessels have to be coated with a thin layer of tin(kalai) from time to time.

USEFULNESS OF CERTAIN ACIDS:

(i) Hydrochloric acid (HCl) produced in the stomach kills the harmful bacteria that may enter into the stomach along with the food we eat.

(ii) Vinegar (acetic acid) is used in the pickling of food as a method of preservation of food.

Base

Substances with bitter taste and soapy touch are regarded as bases. Since many bases like sodium hydroxide and potassium hydroxide have corrosive action on the skin and can even harm the body, so according to the modern definition a base may be defined as a substance capable of releasing one or more OH- ions in aqueous solution.

Alkalies:

Some bases like sodium hydroxide and potassium hydroxide are water soluble. These are known as alkalies. Therefore water soluble bases are known as alkalies eg. KOH, NaOH. A list of a few typical bases along with their chemical formulae and uses is given below:

| Name | Commercial Name | Chemical Formula | Uses |

| Sodium hydroxide | Caustic Soda | NaOH | In manufacture of soap, paper, pulp, rayon, refining of petroleum etc. |

| Potassium hydroxide | Caustic Sba | KHO | In alkaline storage batteries, manufacture of soap, absorbing CO2 gas etc. |

| Calcium hydroxide | Slaked lime | Ca(OH)2 | In manufacture of bleaching powder softening of hard water etc. |

| Magnesium hydroxide | Milk of Magnesia | Mg(OH)2 | As an antacid to remove acidity from stomach |

| Aluminum hydroxide | – | Al(OH)3 | As foaming agent in fire extinguishers. |

| Ammonium hydroxide | – | NH4OH | In removing greases stains from cloths and in cleaning window panes. |

PHYSICAL PROPERTIES OF BASES

(i) Bitter taste: Almost all basic substances have a bitter taste.

(ii) Action on litmus solution: Bases turn red litmus solution into blue.

(iii) Action on methyl orange: Bases turn methyl orange into yellow.

(iv) Action on phenolphthalein: Bases turn phenolphthalein into pink.

(v) Conduction of electricity: Like acid, the aqueous solution of a base also conducts electricity.

CHEMICAL PROPERTIES OF BASES

REACTION OF BASES WITH METALS:

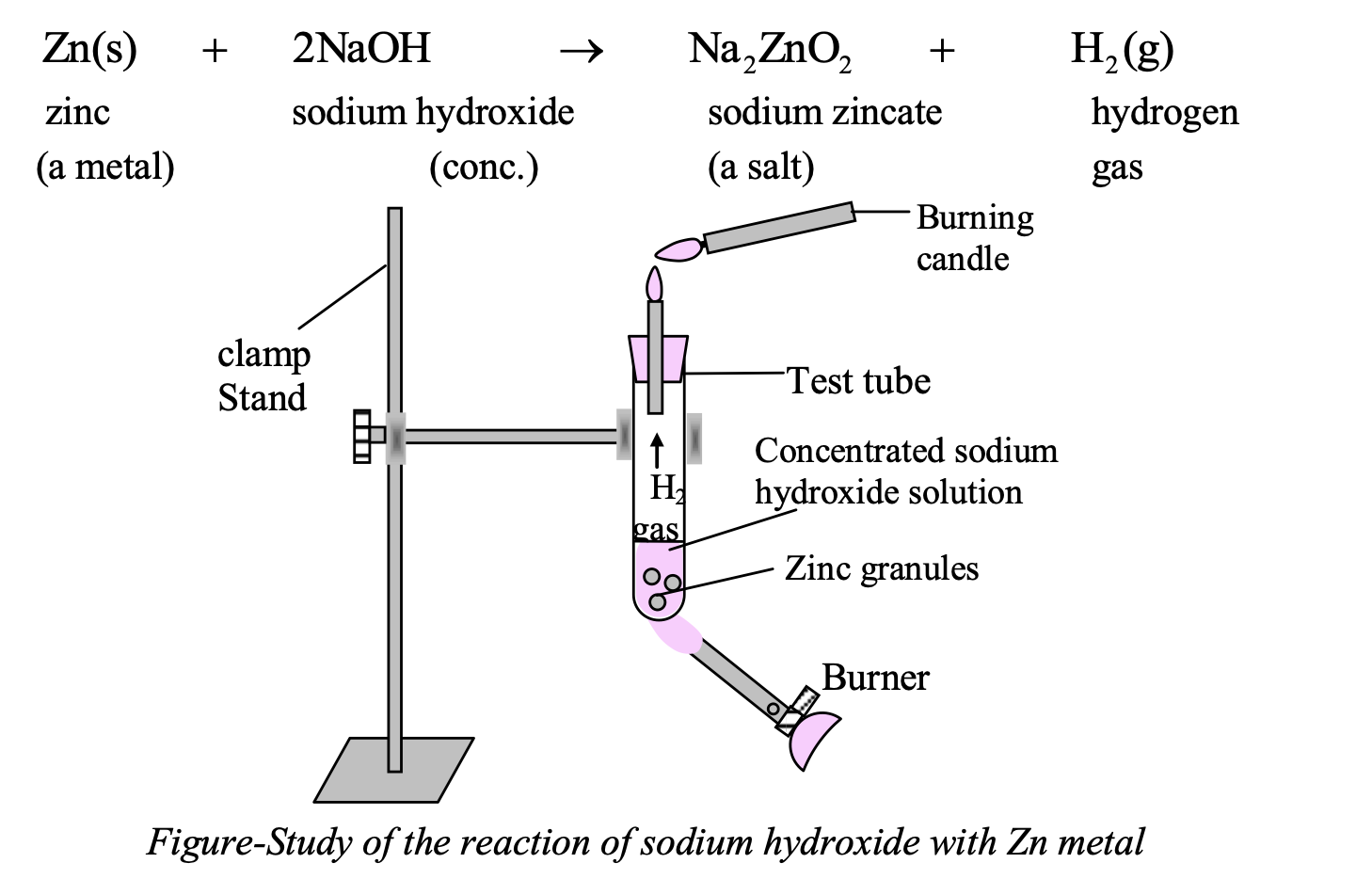

Metals like zinc, tin and aluminum react with strong alkalies like NaOH (caustic soda), KOH (caustic potash) to evolve hydrogen gas.

Zn(s) + 2NaOH(aq) → Na2ZnO2 (aq) + H2 (g)

Sodium zincate

Sn(s) + 2NaOH(aq) → Na2SnO2 (aq) + H2 (g)

Sodium stannite

2Al(s) + 2NaOH + 2H2O → 2NaAlO2 (aq) + 3H2 (g)

Sodium meta aluminate

Experiment: Take 2-3 pieces of zinc granules in a test tube and add about 2-3 ml of conc. NaOH solution in to it and warm the contents.

Observation: There is evolution of H2 gas which burns with a pop sound (on bringing a burning candle near the mouth of tube).

The reaction involved is:

REACTION OF BASES WITH ACIDS (NEUTRALIZATION REACTION)

When a base reacts with an acid then salt and water are formed

i.e. Base + Acid → Salt + Water

This reaction is called neutralization reaction, because when base and acid react with each other, they neutralize each other's effect (i.e. acid destroys the basic property of a base and a base destroys the acidic property of an acid)

(i) NaOH(aq) + HCl(aq)→ NaCl(aq) + H2O(l) sodium hydroxide hydrochloric acid sodium chloride water (base) (acid) (salt)

(ii) 2NaOH(aq) + H2SO4(aq) → Na2SO4(aq) + 2H2O(l) sodium hydroxide sulphuric acid sodium sulphate water (base) (acid) (salt)

Conclusion: Reaction of a base with an acid is a neutralization of an acid by base

REACTION OF BASE WITH NON-METAL OXIDE:

Bases react with non-metal oxide to form salt and water

i.e. Non-metal oxide + Base Salt + water

This reaction is similar to the neutralization reaction between acid and base to form salt and water. Thus, the reaction between bases and non-metal oxides is a kind of neutralization reaction and shows that non-metal oxides are acidic oxides.

Reaction of calcium hydroxide (lime water) with carbon dioxide.

Calcium hydroxide (lime water) is a base and carbon dioxide (CO2) is a non-metal oxide, so when they react with each other, salt and water are produced according to the reaction:

Ca(OH)2 (aq) + CO2(g) → CaCO3(g) + H2O(l)

calcium hydroxide carbondioxide calcium water (lime water) (non-metal oxide) carbonate (base) (salt)

2NaOH(aq) + CO2(g) → Na2 CO3(aq) + H2O(l)

Ca(OH)2 (s) + SO2(g) → CaSO3(aq) + H2O(l)

Conclusion: Reactions of bases with non-metal oxides are neutralization reactions which show the acidic nature of non-metal oxide.

CLASSIFICATION OF BASES ON THE BASIS OF DEGREE OF IONIZATION

The bases are classified into two categories on the basis of degree of ionization as follows:

(i) Strong bases

(ii) Weak bases

Strong base: A base contains one or more hydroxyl (OH) groups which it releases in aqueous solution upon ionisation. Bases which are almost completely ionised in water, are known as strong bases.

e.g. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH), potassium hydroxide (OH) groups which it releases in aqueous solution upon ionisation. Bases which are almost completely ionised in water, are known as strong bases.

NaOH(s) + Water → Na+(aq) + OH-(aq)

KOH(s) + Water → K+(aq) + OH-(aq)

Both NaOH and KOH are deliquescent in nature which means that they absorb moisture from air and get liquefied.

Weak bases:

Bases that are feebly ionised on dissolving in water and reduce a low concentration of hydroxyl ions are called weak bases.

eg. Ca(OH)2, NH4OH

(i) NH4OH + H2O ⇌ NH4+ (aq) + OH⁻(aq) Ammonium hydroxide Water Ammonium ion hydroxide ion

or

NH4OH (aq) ⇌ NH4+ (aq) + OH-(aq)

(ii) Ca(OH)2 + H2O ⇌ Ca2+(aq) + 2OH-(aq) calcium hydroxide Water calcium ion hydroxide ion (lime water)

or

Ca(OH)2(aq) ⇌ Ca2+(aq) + 2OH-(aq)

(iii) Mg(OH)2 + H2O ⇌ Mg2+(aq) + 2OH⁻(aq) magnesium hydroxide Water magnesium ion hydroxide ion

or

Mg(OH)2(aq) ⇌ Mg2+(aq) + 2OH-(aq)

Conclusion:

Greater the degree of ionization, greater is the amount of OH-(aq) ions produced in the solution and thus stronger is the base (or greater is the strength of base).

Smaller the degree of ionization, smaller is the amount ofOH- (aq) ions produced in the solution and thus weaker is the base (or lesser is the strength of base). Thus, strength of base is directly proportional to the degree of ionization.

Strength of base μ Degree of ionization.

Dilution of base: an exothermic reaction

Like acids, dilution of bases with water or mixing of bases with water is an exothermic process e.g. if we dissolve bases like NaOH, KOH in water, the solution is found to be hotter. This shows that dissolution of bases in water is an exothermic process.

Effect of dilution on strength of a base:

Like acids, on dilution of base with water, [OH-] in the solution decrease and thus, solution becomes less basic (or strength of base decrease)

Important Note: Basic strength of a base is affected by two factors:

(i) Degree of ionization of a base i.e. strength of base ∝ degree of ionization. Greater the degree of ionization, greater will be [OH-] in the solution and thus greater will be the strength of a base (or stronger will be a base).

Similarly, smaller the degree of ionization, smaller will be [OH-] in the solution and thus, lesser will be the strength of the base (or weaker will be the base).

(ii) Dilution of a base: Strength of a base ∝ 1/(dilution of a base). Greater the dilution of a base, lesser will be [OH-] in the solution and thus, lesser will be the strength of the base (or weaker will be the base).

Similarly, smaller the dilution of a base, greater will [OH-] in the solution and thus, greater will be the strength of the base (or stronger will be the base).

Comparison Between properties of acids and bases:

| Acids | Bases |

| 1. Sour in taste. | 1. Bitterness in taste. |

| 2. Change colours of indicators e.g. Litmus turns from blue to red, phenolphthalein remains colourless. | 2. Change colours of indicators e.g., litmus turns from red to blue, phenolphthalein turns from colourless to pink. |

| 3. Shows electrolytic conductivity in aqueous solution. | 3. Shows electrolytic conductivity in aqueous solutions. |

| 4. Acidic properties disappear when reacts with bases (Neutralisation). | 4. Basic properties disappear when reacts with acids (Neutralisation). |

| 5. Acids decompose carbonate salts. | 5. No decomposition of carbonate salts by bases. |

INDICATORS

Indicator indicates the nature of particular solution whether acidic, basic or neutral. Apart from this, indicator also represents the change in nature of the solution from acidic to basic and vice versa. Indicators are basically coloured organic substances extracted from different plants.

INDICATORS SHOWING DIFFERENT COLOURS IN ACIDIC AND BASIC MEDIUM

LITMUS SOLUTION:

Litmus solution is a purple coloured dye extracted from the lichen plant. It is very interesting to note that litmus solution (purple colour) itself is neither acidic nor basic. To use it as an indicator, it is made acidic or alkaline.

The alkaline form of litmus solution is blue in colour and called blue litmus solution.

The acidic form of litmus solution is red in colour and called red litmus solution.

Blue litmus solution (blue in colour): It is obtained by making the purple litmus extract alkaline. Thus, it is basic in nature and acts as an acid-indicator by giving a characteristic change in its colour in acids.

Red litmus solution (red in colour): It is obtained by making the purple litmus extract acidic. Thus it is acidic in nature and acts as a base-indicator by giving a characteristic change in its colour in bases.

Now questions arise:

(i) How do they (litmus solutions) act as acid –base indicators?

(ii) How do they change their colours in acids and bases?

(iii) How do they test whether the given substance is acidic or basic?

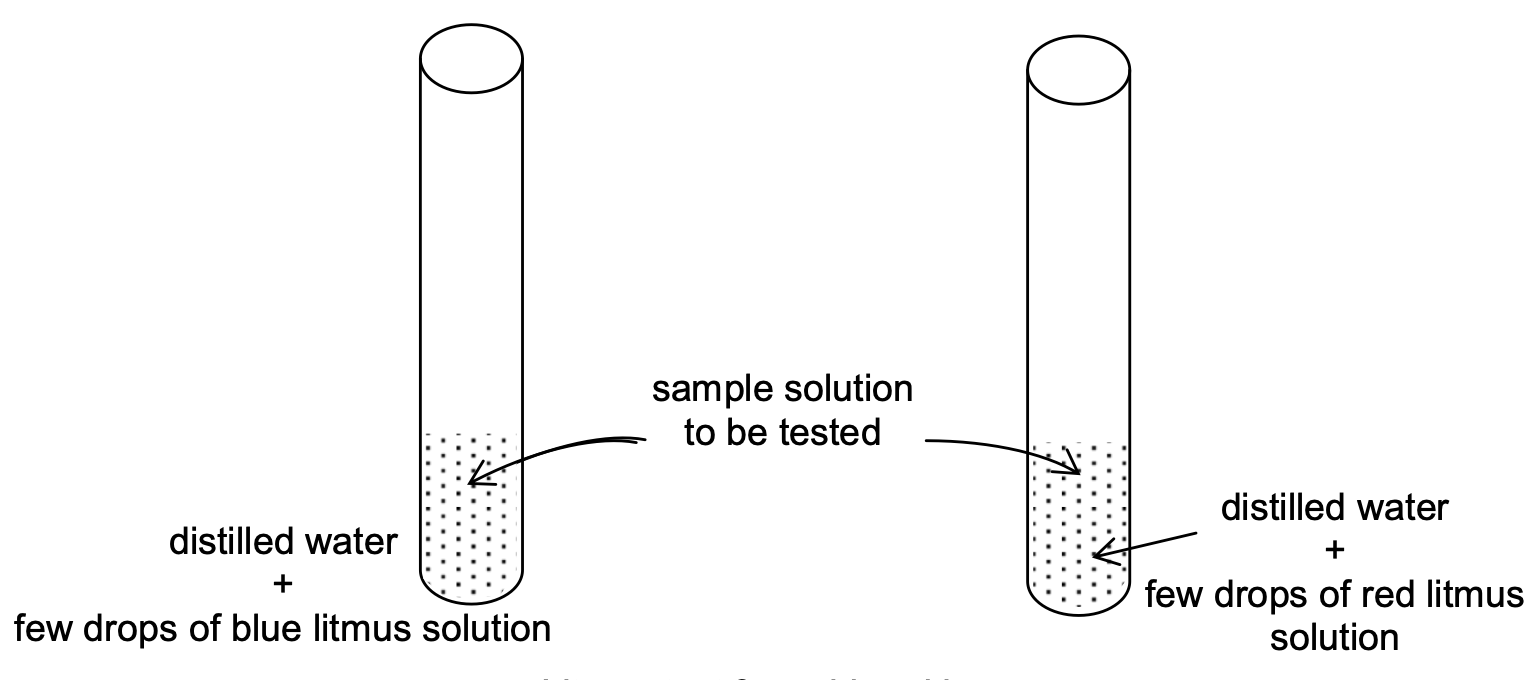

Experiment to test: Take about 2 - 4 ml of distilled water in two test tubes and add 1-2 drops of blue litmus solution in one test tube and red litmus in another test tube. Now add the sample solution of the substance to be tested in both test tubes (fig.)

Observation:

(i) Blue litmus solution turns red in acidic medium i.e. blue litmus solution changes into red if the sample solution (to be tested) is acidic.

(ii) Red litmus solution turns blue in basic medium i.e red litmus solution changes into blue

if the sample solution (to be tested) is basic.

The above observation can be shown more clearly by taking examples of some commonly used substance as follows.

Table 2

| Acidic substance turning blue litmus solution into red | Basic substance turning red litmus solution into blue |

|

Vinegar Lemon Juice Tamarind (imli) Sour milk or curd Proteins Tomatoes Apples Oranges Juice of unripe mangoes |

Baking soda solution Washing soda solution Bitter gourd (karela) extract Cucumber (kheera) extract |

It is clear from the above that blue litmus solution acts as acid indicator by giving red colour in acidic medium and red litmus solution acts as base indicator by giving blue colour in basic medium.

Thus litmus solution acts as an acid-base indicator.

TURMERIC (HALDI):

Turmeric used in kitchen can also be used to test a basic solution i.e. it act as base indicator by giving brown colour in basic medium. In other words yellow colour of haldi turns into brown in basic substances (due to base present in them) and thus distinguishes between acids and bases.

e.g. While eating food, if curry falls on the white clothes, a yellow stain is produced in the clothes. When we apply soap solution (basic in nature) on the cloth, the yellow stain becomes brown due to base present in soap solution.

This example shows that turmeric (haldi) act as base indicator by giving brown colour in basic substances.

SYNTHETIC INDICATORS:

The synthetic chemical substances which change their colour in acids and bases and thus distinguish between them are called synthetic indicators. Since they distinguish between acids and bases, so they are also called synthetic acid base indicators. The two most common synthetic indicators are

(a) Phenolphthalein and

(b) Methyl orange.

Now questions arise

(i) How do they (synthetic indicators) act as acid-base indicators?

(ii) How do they change their colour in acids and bases?

(iii) How do they test whether the given substance is acidic or basic?

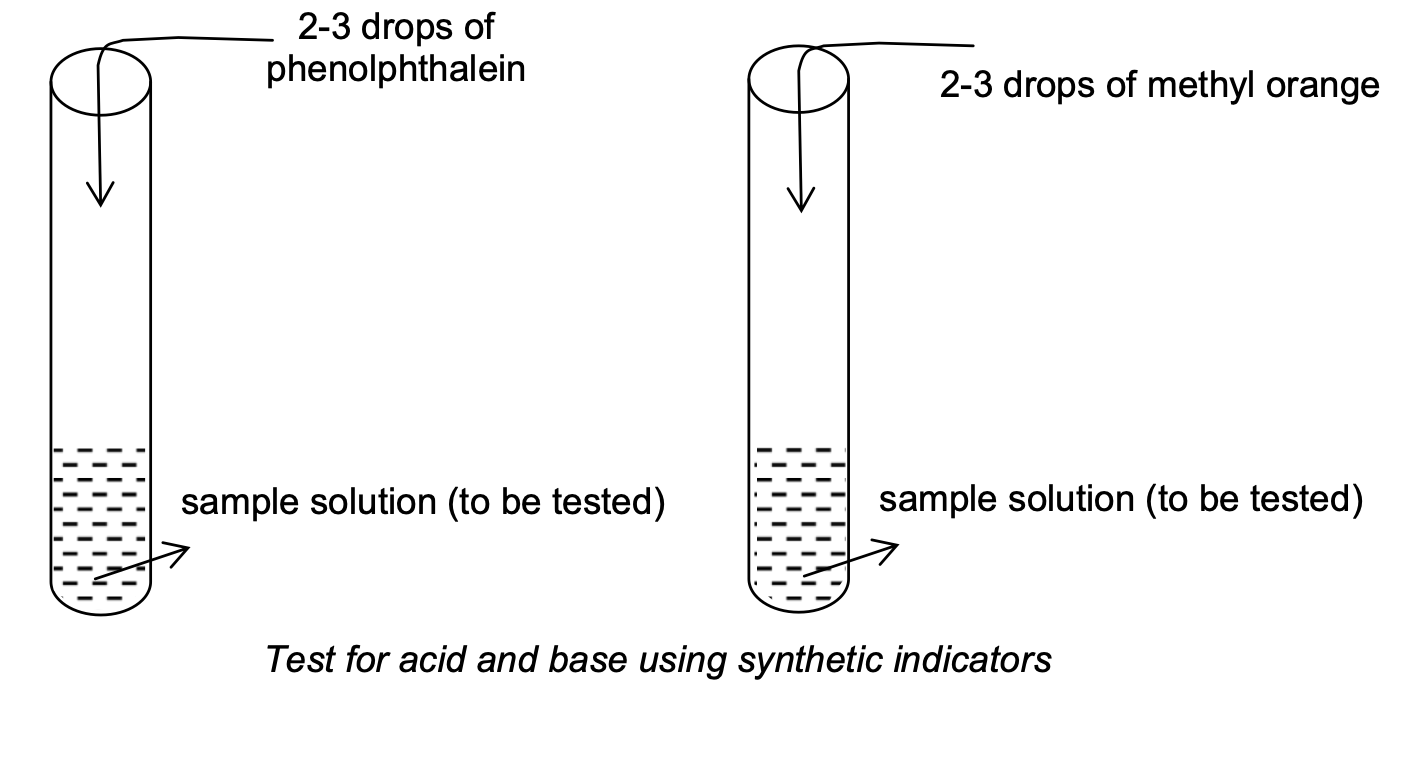

Experiment to test: Take about 2 ml of sample solution (substance to be tested) in two test tubes and add 2-3 drops of phenolphthalein and methyl orange (synthetic acid-base indicators) to then as shown in figure.

Observation:

(a) Colour changes which take place in phenolphthalein are

(i) Phenolphthalein (whose natural colour is colourless) is colourless in acidic medium.

(ii) Phenolphthalein gives pink colour in basic medium or solution.

(b) Colour changes which take place in methyl orange are

(i) Methyl orange (whose natural colour is orange) gives pink colour in acidic medium or solution.

(ii) Methyl orange gives yellow colour in basic medium or solution.

The above observation can be shown clearly by taking examples of some commonly used substances as follows:

Table - 3

| Acidic substances turning methyl orange into pink and phenolphthalein remaining colourless | Basic substances turning methyl orange into yellow and phenolphthalein into pink |

|

Vinegar Lemon Juice Tamarind (imli) Sour milk or curd Proteins Tomatoes Oranges Juice of unripe mangoes |

Baking soda solution Washing soda solution Bitter gourd (karela) extract Cucumber (kheera) extract |

Now, if we see table 2 and table 3 observations, then we conclude that acid – base indicators like (litmus solution i.e. blue litmus solution and red litmus solution), phenolphthalein and methyl orange distinguishes between acids and bases by giving different colours (table 4)

Table – 4

| Sample solution | Red litmussolution | Blue litmussolution | Phenolphthalein indicator | Methyl orange indicator |

|

Vinegar |

No colour change |

Red |

Colourless |

Pink |

|

Lemon juice |

No colour change |

Red |

Colourless |

Pink |

|

Washing soda solution |

Blue |

No colour change |

Pink |

Yellow |

|

Baking soda solution |

Blue |

No colour change |

Pink |

Yellow |

|

Tamarind (imli) |

No colour change |

Red |

Colourless |

Pink |

|

Sour milk or curd |

No colour change |

Red |

Colourless |

Pink |

|

Proteins |

No colour change |

Red |

Colourless |

Pink |

|

Bitter gourd (karela) extract |

Blue |

No colour change |

Pink |

Yellow |

|

Oranges |

No colour change |

Red |

Colourless |

Pink |

|

Cucumber (kheera) Extract |

Blue |

No colour change |

Pink |

Yellow |

|

Tomatoes |

No colour change |

Red |

Colourless |

Pink |

|

Juice of unripe mangoes |

No colour change |

Red |

Colourless |

Pink |

The above observation can be shown more clearly as follows

Table – 5

| Indicator | Colour in acidic solution | Colour in basic solution |

|

Blue litmus solution Red litmus solution Phenolphthalein Methyl orange |

Red No colour change Colourless Pink |

No colour change Blue Pink Yellow |

It is clear from the above table that to test whether a substance is acidic or basic we can use any one of the above indicators. The change in colour with these indicators for the substance taken, shows its acidic or basic nature.

INDICATORS GIVING DIFFERENT ODOURS IN ACIDIC AND BASIC MEDIUM

(Olfactory Indicators)

There is another type of acid-base indicator which distinguishes between acids and base by giving different odour or smell in acidic and basic medium i.e. they give one type of odour or smell in acidic medium and a different odour or smell in basic medium and thus it can distinguish between acids and bases.

These indicators which give different odours or smells in acidic and basic medium are called olfactory indicators.

A few of these are given below:

(a) onion odoured cloth strip

(b) vanilla extract

(c) clove oil

Test with onion odoured cloth strip:

Take 1-2 ml of dil HCl in a test tube and add 1-2 ml of a basic solution like dil NaOH solution in another test tube. Add a small cloth strip treated with onion extract in each test tube and shake well.

Observation:

(i) acidic solution like dil HCl does not destroy the smell of onion.

(ii) basic solution like dil NaOH destroy the smell of onion.

Thus onion odoured cloth strip can be used as a test for acids and bases.

Test with vanilla extract:

Take 1-2 ml of acidic solution like dil HCl in one test tube and 1-2 ml of dil NaOH (basic solution) in another test tube. Add a few drops of vanilla extract (having characteristic pleasant smell) in each test tube and shake well.

Observation:

(i) Acidic solution like dil HCl does not destroy the characteristic smell of vanilla extract.

(ii) Basic solution like dilute NaOH destroy the smell of vanilla extract.

Thus vanilla extract can be used to test for acids and bases.

Test with clove oil:

Take about 1-2 ml of dil HCl in one test tube and 1-2 ml of dil NaOH in another test tube. Add a few drops of clove oil extract (having a characteristic smell or odour) in each test tube and shake well.

Observation:

(i) Acidic solution like dil HCl does not destroy the characteristic smell or odour of clove oil.

(ii) Basic solution like dil NaOH destroy the odour or smell of clove oil.

Thus clove oil can be used to test for acids and bases.

The above observations can be shown more clearly as follows:

Table - 6

|

Indicator |

Odour or smell in acidic solution |

Odour or smell in basic solution |

|

Onion Odoured cloth strip Clove oil Vanilla extract |

No change No change No change |

Cannot be detected Cannot be detected Cannot be detected |

It is clear from the above table that the olfactory indicators like clove oil, vanilla extract, onion odoured cloth strip, etc. can distinguish between acids and bases by giving different odours or smells in acidic and basic medium.

NEUTRALISATION:

It may be defined as a reaction between acid and base present in aqueous solution to form salt and water.

HCl (aq) + NaOH (aq) → NaCl (aq) + H2O (l)

Basically neutralisation is the combination between H+ ions of the acid with OH- ions of the base to form H2O.

For e.g. H+(aq) + Cl-(aq) + Na+(aq) + OH-(aq) → Na+(aq) + Cl-(aq) + H2O(l)

H+(aq) + OH-(aq) → H2O(l)

Neutralisation reaction involving an acid and base is of exothermic nature. Heat is evolved in all neutralisation reactions. If both acid and base are strong, the value of heat energy evolved remains same irrespective of their nature.

For e.g.

HCl(aq)+ NaOH(aq) → NaCl(aq) + H2O(l) + 57.1kJ Strong acid Strong Base

HNO3(aq)+ KOH(aq) → KNO3(aq) + H2O(l) + 57.1kJ Strong acid Strong Base

Strong acids and strong bases are completely ionised of their own in the solution, No energy is needed for their ionisation. Since the cation of base and anion of acid on both sides of the equation cancels out completely, the heat evolved is given by the following reaction

H+(aq) + OH-(aq) → H2O(l) + 57.1 kJ

Reaction of strong acid and strong base evolves 57.14 J.

APPLICATIONS OF NEUTRALISATION:

(i) People particularly of old age suffer from acidity problems in the stomach which is caused mainly due to release of excessive gastric juices containing HCI. The acidity is neutralised by antacid tablets which contain sodium hydrogen carbonate (baking soda), magnesium hydroxide etc.

(ii) The stings of bees and ants contain formic acid. Its corrosive and poisonous effect can be neutralised by rubbing soap which contains NaOH (an alkali).

(iii) The stings of wasps contain an alkali and its poisonous effect can be neutralised by an acid like acetic acid (present in vinegar).

(iv) Farmers generally neutralise the effect of acidity in the soil caused by acid rain by adding slaked lime (Calcium hydroxide) to the soil.

Strength of Acid and Base Solution: pH Scale

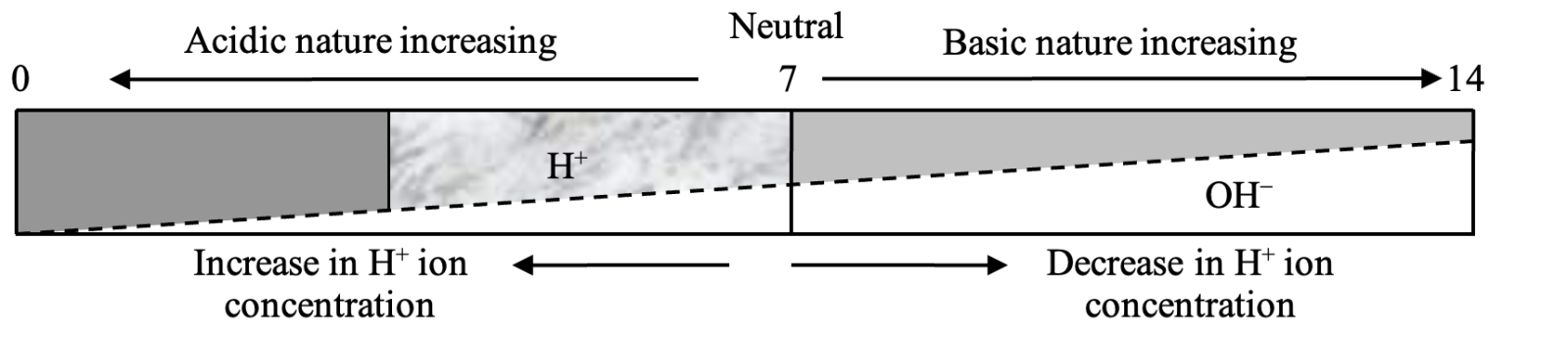

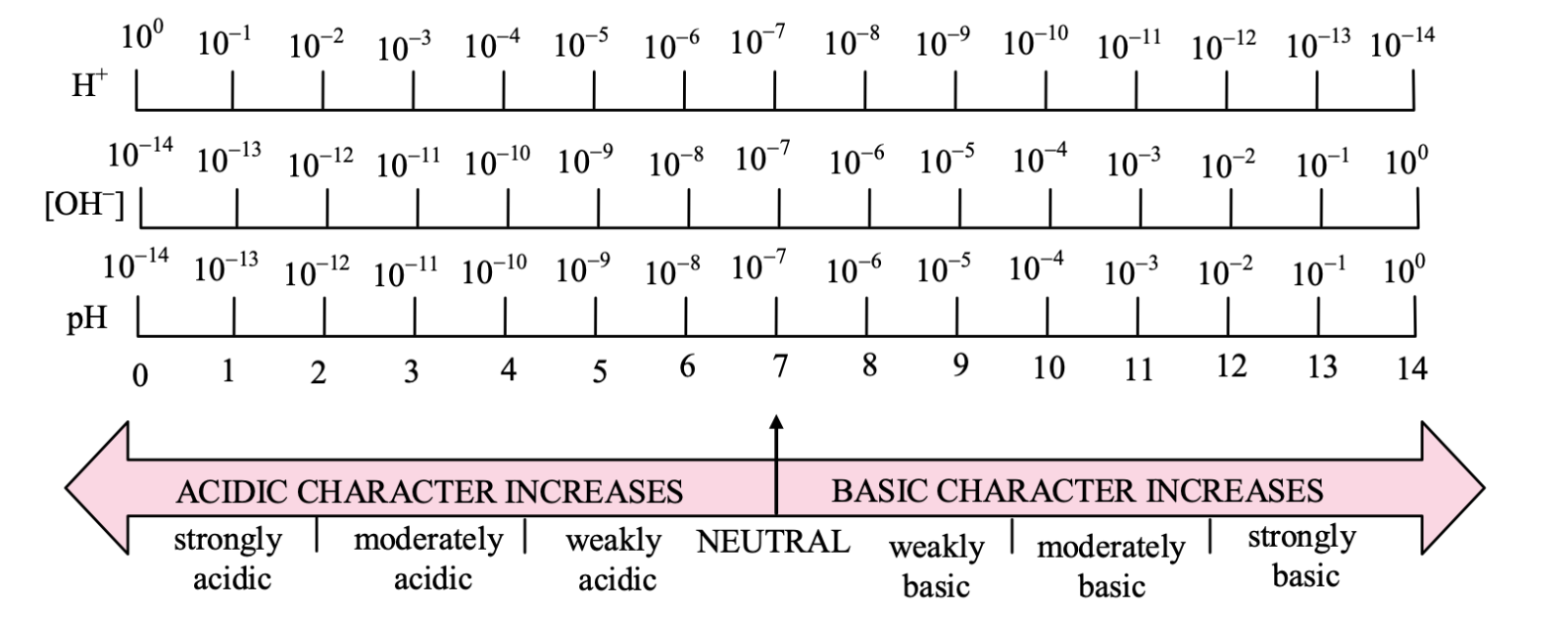

pH scale: A scale developing for measuring hydrogen ion concentration in a solution called pH scale, has been developed by S.P.L. sorrensen. The P in pH stands for 'potenz' in German power. On the pH scale we can measure pH from O (very acidic) to 14(very alkaline). pH should be thought of simply as a number which indicates the acidic or basic nature of solution. Higher the hydrogen ion concentration, Lower is the pH scale.

(i) For acidic solution, pH < 7

(ii) For alkaline solution, pH > 7

(iii) For neutral solution, pH = 7

Strength of Acid and Base Solution: pH Scale

pH scale: A scale developing for measuring hydrogen ion concentration in a solution called pH scale, has been developed by S.P.L. sorrensen. The P in pH stands for 'potenz' in German power. On the pH scale we can measure pH from O (very acidic) to 14(very alkaline). pH should be thought of simply as a number which indicates the acidic or basic nature of solution. Higher the hydrogen ion concentration, Lower is the pH scale.

(i) For acidic solution, pH < 7

(ii) For alkaline solution, pH > 7

(iii) For neutral solution, pH = 7

pH is defined as negative logarithm of [H+] or [H3O+]

i.e. pH = −log[H+] or pH = −log[H3O+]

e.g. if [H+] = 10-1 mol L-1, then pH = −log(10-1) = log10 = 1

if [H+] = 10-2 mol L-1, then pH = −log(10-2) = 2log10 = 2

It is clear from the above expression that pH of a solution is the magnitude of the negative power to which 10 must be raised to express the [H+] of the solution in mol L-1.

In other words, pH stands for power of hydrogen ions (p stands for power and H stands for hydrogen)

e.g.

If [H+] = 10⁻¹ mol L-1, then pH = 1

If [H+] = 10-2 mol L-1, then pH = 2

If [H+] = 10-6 mol L-1, then pH = 6 and so on

and If [OH-] = 10-6 mol L-1, then [H+] = 10-8 mol L-1 and pH = 8

[∵ [H+][OH-] = 10-14 mol L-1 at 298K ⇒ 10-6 × 10-8 = 10-14 mol L-1]

similarly if [OH⁻] = 10-14 mol L-1 then [H+] = 100 ∵[H+][OH-] = 10-14

so that [100 × 10⁻-14 = 10-14]

and pH = 0

if [OH-] = 100 mol L-1, [H⁺] = 10-14 [so that 10-14 × 100 = 10-14] and pH = 14 and so on

pH values for acidic or basic or neutral solution in terms of [H+] can be expressed as follows:

FOR A NEUTRAL SOLUTION (OR WATER)

[H⁺] = [OH⁻] = 10⁻⁷ mol L⁻¹

⇒ its pH = 7 (magnitude of negative power to which 10 must be raised to express [H⁺])

FOR AN ACIDIC SOLUTION

[H⁺] > [OH⁻]

or [H⁺] > 10⁻⁷ mol L⁻¹ (i.e. 10⁻⁶, 10⁻⁵, 10⁻⁴ etc.)

⇒ its pH < 7 (i.e. 6, 5, 4, ....0)

FOR A BASIC SOLUTION

[OH⁻] > [H⁺]

or [OH⁻] > 10⁻⁷ mol L⁻¹ (i.e. 10⁻⁶, 10⁻⁵, 10⁻⁴ etc.)

or [H⁺] < 10⁻⁷ mol L⁻¹ (i.e. 10⁻⁸, 10⁻⁹, 10⁻¹⁰ etc so that [H⁺][OH⁻] = 10⁻¹⁴)

⇒ its pH > 7 (i.e. 8, 9, 10, ....14)

Hence, acidic or basic strength or neutral nature of solution may be expressed on the pH scale from 0 to 14 as follows:

Conclusion: From the above figure, we lead to a conclusion that

(i) for a neutral solution, pH = 7

(ii) for a basic solution, pH > 7

(iii) for an acidic solution, pH < 7

Universal indicator papers for pH values:

Indicators like litmus, phenolphthalein and methyl orange are used in predicting the acidic and basic characters of the solutions. However universal indicator papers have been developed to predict the pH of different solutions. Such papers represent specific colours for different concentrations in terms of pH values.

The exact pH of the solution can be measured with the help of pH meter which gives instant reading and it can be relied upon.

pH values of a few common solutions are given below :

| Solution | Approximate pH | Solution |

Approximate pH |

|

Gastric Juices |

1.0 - 3.0 |

Pure water |

7.0 |

|

Lemon juices |

2.2-2.4 |

Blood |

7.36-7.42 |

|

Vinegar |

3.0 |

Baking soda solution |

8.4 |

|

Beer |

4.0-5.0 |

Sea water |

9.0 |

|

Tomato juice |

4.1 |

Washing soda solution |

10.5 |

|

Coffee |

4.5-5.5 |

Lime water |

12.0 |

|

Acid rain |

5.6 |

House hold ammonia |

11.9 |

|

Milk |

6.5 |

Sodium hydroxide |

14.0 |

|

Saliva |

6.5-7.5 |

(b) Significance of pH in daily life:

(i) pH in our digestive system: Dilute hydrochloric acid produced in our stomach helps in the digestion of food. However, excess of acid causes indigestion and leads to pain as well as irritation. The pH of the digestive system in the stomach will decrease. The excessive acid can be neutralised with the help of antacid which are recommended by the doctors. Actually, these are group of compounds (basic in nature) and have hardly any side effects. A very popular antacid is 'Milk of Magnesia' which is insoluble magnesium hydroxide. Aluminium hydroxide and sodium hydrogen carbonate can also be used for the same purpose. These antacids will bring the pH of the system back to its normal value. The pH of human blood varies from 7.36 to 7.42. It is maintained by the soluble bicarbonates and carbonic acid present in the blood. These are known as buffers.

(ii) pH change leads to tooth decay: The white enamel coating on our teeth is of insoluble calcium phosphate which is quite hard. It is not affected by water. However, when the pH in the mouth falls below 5.5 the enamel gets corroded. Water will have a direct access to the roots and decay of teeth will occur. The bacteria present in the mouth break down the sugar that we eat in one form or the other to acids; Lactic acid is one of these. The formation of these acids causes decrease in pH. It is therefore advisable to avoid eating sugary foods and also to keep the mouth clean so that sugar and food particles may not be present. The tooth pastes contain in them some basic ingredients and they help in neutralising the effect of the acids and also increasing the pH in the mouth.

(iii) Role of pH in curing stings by insects: The stings of bees and ants contain methanoic acid (or formic acid). When stung, they cause lot of pain and irritation. The cure is in rubbing the affected area with soap. Sodium hydroxide present in the soap neutralises acid injected in the body and thus brings the pH back to its original level bringing relief to the person who has been stung. Similarly, the effect of stings by wasps containing alkali is neutralised by the application of vinegar which is ethanoic acid (or acetic acid)

(iv) Soil pH and plant growth: The growth of plants in a particular soil is also related to its pH. Actually, different plants prefer different pH range for their growth. It is therefore, quite important to provide the soil with proper pH for their healthy growth. Soils with high iron minerals or with vegetation tend to become acidic. The soil pH can reach as low as 4.The acidic effect can be neutralised by 'liming the soil' which is carried by adding calcium hydroxide. These are all basic in nature and have neutralising effect. Similarly, the soil with excess of lime stone or chalk is usually alkaline. Sometimes, its pH reaches as high as 8.3 and is quite harmful for the plant growth. In order to reduce the alkaline effect, it is better to add some decaying organic matter (compost or manure). The soil pH is also affected by the acid rain and the use of fertilizers. Therefore soil treatment is quite essential.

SALTS

A substance formed by neutralization of an acid with a base is called a salt. For e.g.

Ca(OH)₂ + H₂SO₄ → CaSO₄ + H₂O

2Cu(OH)₂ + 4HNO₃ → 2Cu(NO₃)₂ + 2H₂O

NaOH + HCl → NaCl + H₂O

CLASSIFICATION OF SALTS:

Salts have been classified on the basis of chemical formulae as well as pH values.

(a) Classification Based on Chemical Formulae

(i) Normal salts: A normal salt is the one which does not contain any ionisable hydrogen atom or hydroxyl group. This means that it has been formed by the complete neutralisation of an acid by a base.

For e.g. NaCl, KCl, NaNO₃, K₂SO₄ etc.

(ii) Acidic salts: An acidic salt is that which contains some replaceable hydrogen atoms. This means that the neutralisation of acid by the base is not complete. For example, sodium hydrogen sulphate (NaHSO₄), sodium hydrogen carbonate (NaHCO₃) etc.

(iii) Basic salts: A basic salt is that which contains some replaceable hydroxyl groups. This means that the neutralisation of base by the acid is not complete. For example, basic lead nitrate Pb(OH)NO₃, Basic lead chloride, Pb(OH)Cl etc.

(b) Classification Based on pH Values:

Salts are formed by the reaction between acids and bases. Depending upon the ^nature of the acids and bases or upon the pH values, the salt solutions are of three types.

(i) Neutral salt solutions: Salt solutions of strong acids and strong bases are neutral and have pH equal to 7. They do not change the colour of litmus solution.

For e.g.: NaCl, KCl, NaNO₃, Na₂SO₄ etc.

(ii) Acidic salt solutions: Salt solutions of strong acids and weak bases are of acidic nature and have pH less than 7. They change the colour of blue litmus to red. For e.g. (NH₄)₂SO₄, NH₄Cl etc. In both these salts, the base NH₄OH is weak while the acids H₂SO₄ and HCl are strong.

(iii) Basic salt solutions: Salt solutions of strong bases and weak acids are of basic nature and have pH more than 7. They change the colour of red litmus solution to blue. For e.g. Na2CO3, K3PO4 etc.

In both the salts, bases NaOH and KOH are strong while the acids H2CO3 and H3PO4 are weak.

Uses of Salt

(i) As a table salt.

(ii) In the manufacture of butter and cheese.

(iii) In the manufacturing of washing soda and baking soda.

(iv) For the preparation of sodium hydroxide by electrolysis of brine.

(v) Rock salt is spread on ice to melt it in cold countries.

Some Important Chemical Compounds

Sodium Chloride - Common salt (table salt):

Sodium chloride (NaCI) also called common salt or table salt is the most essential part of our diet. Chemically it is formed by the reaction between solutions of sodium hydroxide and hydrochloric acid. Sea water is the major source of sodium chloride where it is present in dissolved form along with other soluble salts such as chlorides and sulphates of calcium and magnesium; It is separated by some suitable methods. Deposits of the salts are found in different parts of the world and are known as rock salt. When pure, it is a white crystalline solid, However, it is often brown due to the presence of impurities.

Occurrence and extraction of common salt:

The common salt occurs naturally in sea water, in land lakes and in rock salt. The extraction of common salt from these sources are given below:

(i) Common salt from sea water

Sea water contains many dissolved salts in it. The major salt present in sea water is common salt (or NaCl). The common salt is obtained from sea water by the process of evaporation which is done as follows:

Sea water is trapped in large shallow pools and allowed to stand there. The sun’s heat evaporates the water slowly and common salt is left behind. This salt contains impurities of MgCl2, MgSO4 etc and thus purified by removing these impurities by suitable method before it is sold in the market.

(ii) Common salt from inland lakes

Large quantities of salt are obtained by natural evaporation of water of inland lakes e.g. Sambhar lake in Rajasthan (India), Great salt lake (Utah, USA) and Lake Elton (Russia).

(iii) Common salt from underground deposits

The large crystals of common salt found in underground ellipsoids is called “Rock salt”. It is usually brown due to presence of impurities in it. Rock salt is mined from underground deposits just like coal.

Common salt is an important starting material for the production of a number of other chemicals such as

- Sodium hydroxide (caustic soda).

- Calcium oxychloride (bleaching powder).

- Sodium carbonate (washing soda) .

- Sodium hydrogen carbonate (baking soda) and many others.

Uses:

(i) Essential for life: Sodium chloride is quite essential for life. Biologically, it has a number of functions to perform such as in muscle contraction, in conduction of nerve impulse in the nervous system and is also converted in hydrochloric acid which helps in the digestion of food in the stomach. When we sweat, there is loss of sodium chloride along with water. It leads to muscle cramps. Its loss has to be compensated suitably by giving certain salt preparations to the patient. Electrol powder is an important substitute of common salt.

(ii) Raw material for chemicals: Sodium chloride is also a very useful raw material for different chemicals. A few out of these are hydrochloric acid (HCl), washing soda (Na2CO3.10H2O), baking soda (NaHCO3) etc. Upon electrolysis of a strong solution of the salt (brine), sodium hydroxide, chlorine and hydrogen are obtained. Apart from these, it is used in leather industry for the leather tanning. In severe cold, rock salt is spread on icy roads to melt ice. It is also used as a fertilizer for sugar beet.

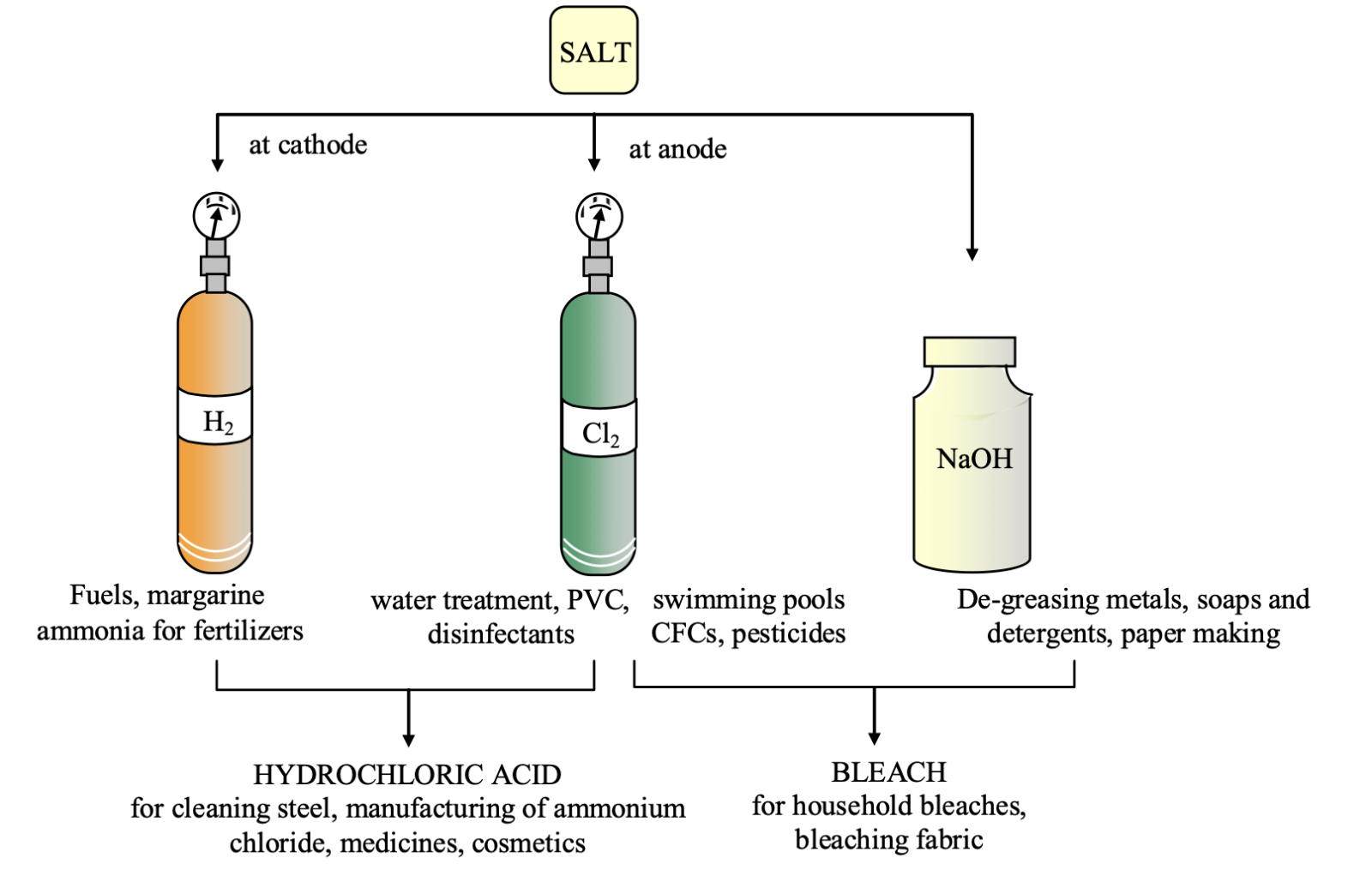

Electrolysis of aqueous solution of NaCl:

2NaCl(s) + 2H₂O(l) - electrolysis → 2NaOH(aq) + Cl₂(g) + H₂(g)

reaction takes place in two steps

(i) 2Cl⁻ → Cl₂(g) + 2e⁻ (anode reaction)

(ii) 2H₂O + 2e⁻ → H₂ + OH⁻ (cathode reaction)

WASHING SODA: (Na₂CO₃.10H₂O)

Chemical name: Sodium carbonate decahydrate

Chemical formula: Na₂CO₃. 10H₂O

Sodium carbonate is recrystallised by dissolving in water to get washing soda it is a basic salt.

Na₂CO₃ + 10H₂O → Na₂CO₃.10H₂O

(Sodium (Washing soda) Carbonate)

(i) Manufacture of washing soda

Washing soda is manufactured from sodium chloride (or common salt) in the following three steps:

Manufacture of sodium hydrogen carbonate (baking soda) by solvay process: A cold and concentrated solution of sodium chloride (brine) is reacted with ammonia and CO₂ to obtain sodium hydrogen carbonate

NaCl + H₂O + NH₃ + CO₂ → NaHCO₃ + NH₄Cl

sodium water ammonia carbondioxide sodium ammonium chloride chloride bicarbonate

Thermal decomposition of sodium hydrogen carbonate (or baking soda): On heating sodium hydrogen carbonate decomposes to form sodium carbonate.

2NaHCO₃ — heat → Na₂CO₃(s) + CO₂(l) + H₂O(g)

sod. hydrogen sod. carbonate carbon dioxide water carbonate (Anhydrous)

Re-crystallization of sodium carbonate (or soda ash):

Anhydrous sodium carbonate (or soda ash) obtained in step 2 is dissolved in water and subjected to re-crystallization. As a result, crystals of washing soda (sodium carbonate decahydrate) are obtained.

Na₂CO₃(s) + 10H₂O(l) → Na₂CO₃.10H₂O(s)

soda ash water washing soda

(ii) Properties of Washing Soda

(a) Colour and state: It is a transparent crystalline solid (when freshly prepared) containing 10 molecules of water of crystallisation.

(b) Action of air: On exposure to air, washing soda crystals lose 9 molecules of water of crystallisation to form a monohydrate which is a white powder

Na₂CO₃.10H₂O(s) - Exposed to air → Na₂CO₃.H₂O + 9H₂O

(transparent crystals)

This process is called efflorescence

(c) Action of heat: On heating, washing soda loses all the molecule of water and becomes anhydrous.

Na₂CO₃.10H₂O - Heat → Na₂CO₃ + 10H₂O

Hydrated washing soda Anhydrous sodium water carbonate (soda ash)

Uses:

(i) It is used as cleansing agent for domestic purposes.

(ii) It is used in softening hard water and controlling the pH of water.

(iii) It is used in manufacture of glass.

(iv) Due to its detergent properties, it is used as a constituent of several dry soap powders.

(v) It also finds use in photography, textile and paper industries etc.

(vi) It is used in the manufacture of borax (Na₂B₄O₇.10H₂O).

BAKING SODA (NaHCO₃)

Baking soda is sodium hydrogen carbonate or sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO₃).

(i) Manufacture of baking soda

(a) On large scale: Baking soda is produced on a large scale by reacting a cold and concentrated solution of sodium chloride (called brine) with ammonia and carbon dioxide.

NaCl + H₂O + NH₃ + CO₂ → NaHCO₃ + NH₄Cl

sodium chloride water ammonia carbon dioxide Baking soda ammonium chloride

This process is called solvay process.

(b) On small scale: On a small scale baking soda can be prepared in the laboratory by passing CO₂ gas through aqueous sodium carbonate solution.

Na₂CO₃ + H₂O + CO₂ → 2NaHCO₃

sodium carbonate water carbon dioxide baking soda

OR

Na₂CO₃(aq) + CO₂ → 2NaHCO₃

(ii) Properties of Baking soda

(a) Colour and state

It is a white crystalline solid.

(b) Alkaline nature

It is mild, non-corrosive base. The alkaline nature of baking soda is due to salt hydrolysis.

NaHCO₃ + H₂O → (hydrolysis) Na⁺(aq) + HCO₃⁻(aq)

baking soda water strong base weak acid

(sodium hydrogen carbonate)

HCO₃⁻ + H₂O ⇌ H₂CO₃ + OH⁻

Thus, salt solution is basic due to hydrolysis of HCO₃⁻ ions

(c) Action of heat

When solid baking soda (or its solution) is heated it decomposes to give sodium carbonate with the evolution of CO₂ gas.

2NaHCO₃ → (Heat) Na₂CO₃ + H₂O + CO₂

baking soda soda carbonate water carbon dioxide gas

The above reaction takes places when baking soda is heated during the cooking of food. Since baking soda gives CO₂ on heating, it is used as a constituent of baking powder.

Uses:

(i) It is used in the manufacture of baking powder. Baking powder is a mixture of potassium hydrogen tartarate and sodium bicarbonate. During the preparation of bread the evolution of carbon dioxide causes bread to rise (swell).

CH(OH)COOK CH(OH)COOK + NaHCO₃ → +CO₂ + H₂O CH(OH)COOH CH(OH)COONa(ii) It is largely used in the treatment of acid spillage and in medicine as soda bicarb, which acts as an antacid.

(iii) It is an important chemical in the textile, tanning, paper and ceramic industries.

(iv) It is also used in a particular type of fire extinguishers. The following diagram shows a fire extinguisher that uses NaHCO₃ and H₂SO₄ to produce CO₂ gas. The extinguisher consists of a conical metallic container (a) with a nozzle (Z) at one end. A strong solution of NaHCO₃ is kept in the container. A glass ampoule (P) containing H₂SO₄ is attached to a knob (K) and placed inside the NaHCO₃ solution. The ampoule can be broken by hitting the knob. As soon as the acid comes in contact with the NaHCO₃ solution, CO₃ gas is formed. When enough pressure in built up inside the container, CO₂ gas rushes out through the nozzle (Z). Since CO₂ does not support combustion, a small fire can be put out by pointing the nozzle towards the fire. The gas is produced according to the following reaction.

2NaHCO₃ (aq) + H₂SO₄(aq) → Na₂SO₄ (aq) + 2H₂O(l) + 2CO₂(g)

BLEACHING POWDER (CaOCl₂.4H₂O, CaCl₂.(OH)₂. H₂O)

Bleaching powder is commercially called 'chloride of lime' or 'chlorinated lime'. It is principally calcium oxychloride having the following formula:

Cl - Ca - OClBleaching powder is prepared by passing chlorine over slaked lime at 313 K.

Ca(OH)₂ (aq) + Cl₂ (g) - 313K → Ca(OCl)Cl(s) + H₂O (g)

Slaked lime Bleaching powder

Note: Bleaching powder is not a compound but a mixture of compounds: CaOCl₂.4H₂O, CaCl₂.Ca(OH)₂.H₂0

(i) Manufacture of bleaching powder

The bleaching powder is manufactured by the action of chlorine gas (produced as a bi-product during manufacture of caustic soda) on dry slaked lime Ca(OH)₂. The reactions involved are:

2NaCl(aq) + 2H₂O(l) electrolysis → 2NaOH(aq) + Cl₂(aq) + H₂

Ca(OH)₂ + Cl₂ → CaOCl₂ + H₂O

Slaked lime chlorine bleaching powder water

Uses:

(i) It is commonly used as a bleaching agent in paper and textile industries.

(ii) It is also used for disinfecting water to make water free from germs.

(iii) It is used to prepare chloroform.

(iv) It is also used to make wool shrink-proof.

Sodium hydroxide NaOH (caustic soda)

Sodium hydroxide is commonly known as caustic soda having chemical formula NaOH. It is a strong base.

(i) Manufacture of sodium hydroxide (NaOH)

Sodium hydroxide is manufactured by the electrolysis of a concentrated aqueous solution of sodium chloride (called brine) i.e., when electricity is passed through a concentrated aqueous solution of sodium chloride (called brine), it decomposes to form sodium hydroxide, chlorine and hydrogen.

2NaCl(aq) + 2H₂O(l) -Electrolysis → 2NaOH(aq) + Cl₂(g) + H₂(g)

sodium chloride water sodium hydroxide chlorine hydrogen (brine) (caustic soda)

This process is called correct-alkali process because of products formed: chlor for chlorine and alkali for sodium hydroxide.