Carbon and Its Compounds: A Complete Chemistry Resource

Introduction to Organic Chemistry

Organic chemistry represents one of the most fascinating branches of chemical science, focusing exclusively on compounds containing carbon. Historically, organic compounds were those isolated from living organisms including substances like urea, sugars, fats, oils, proteins, and vitamins derived from plants and animals. Modern organic chemistry has expanded this definition to encompass the study of hydrocarbons and their derivatives, recognizing carbon's unique ability to form an extraordinary variety of stable compounds.

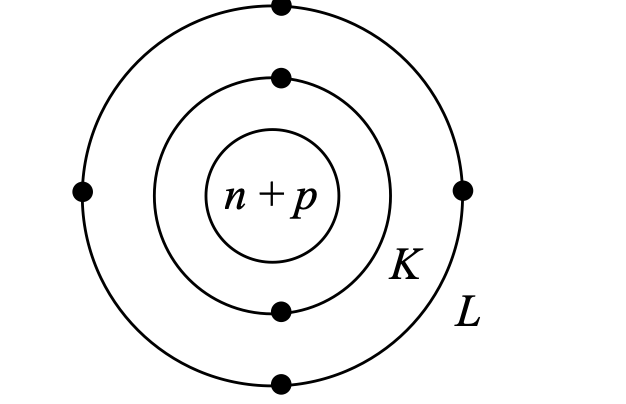

The significance of carbon in chemistry cannot be overstated. This non-metallic element with atomic number 6 and atomic mass 12 possesses four valence electrons in its outermost shell, giving it a valency of four. This tetravalency enables carbon to form four covalent bonds with other atoms, creating the structural foundation for millions of known organic compounds far exceeding the number of compounds formed by all other elements combined.

The Unique Properties of Carbon

Electronic Configuration and Bonding Capacity

Carbon's electronic configuration (K=2, L=4) places it in a unique position on the periodic table. With four valence electrons, carbon requires four additional electrons to achieve the stable octet configuration of the nearest noble gas. Rather than gaining or losing four electrons—which would require prohibitive amounts of energy carbon achieves stability through electron sharing, forming covalent bonds.

This bonding strategy offers several advantages. Forming a C⁴⁺ cation would require removing four electrons against strong nuclear attraction, while forming a C⁴⁻ anion would challenge the nucleus to hold ten electrons with only six protons. Instead, carbon's covalent bonding mechanism allows for stable, energetically favorable molecular structures.

Catenation: The Self-Linking Property

One of carbon's most remarkable properties is catenation the ability to form stable bonds with other carbon atoms, creating chains and rings of virtually unlimited length. This property results from three key factors:

- Small atomic size: Carbon's compact atomic radius allows for effective orbital overlap

- Optimal electronic configuration: Four valence electrons provide maximum bonding versatility

- Strong C-C bonds: Carbon-carbon single bonds possess exceptional strength (348 kJ/mol)

Carbon chains can be straight, branched, or cyclic, and may contain single, double, or triple bonds. This structural diversity forms the basis for the vast array of organic compounds, from simple methane (CH₄) to complex biological macromolecules like proteins and DNA

Chemical Bonding in Carbon Compounds

Covalent Bond Formation

Carbon compounds predominantly feature covalent bonding, where atoms share electron pairs to achieve stable electronic configurations. This bonding type contrasts sharply with ionic bonding, where complete electron transfer occurs between atoms.

Key characteristics of covalent compounds:

- Consist of discrete molecules rather than ionic lattices

- Generally exhibit low melting and boiling points due to weak intermolecular forces

- Poor electrical conductors (no free ions or electrons)

- Soluble in non-polar solvents; insoluble in polar solvents like water

- React through molecular mechanisms, typically slower than ionic reactions

Types of Covalent Bonds

Carbon forms three types of covalent bonds based on electron pair sharing:

Single bonds (C–C): One pair of electrons shared between atoms (bond length: 154 pm; bond energy: 348 kJ/mol)

Double bonds (C=C): Two pairs of electrons shared (bond length: 134 pm; bond energy: 599 kJ/mol)

Triple bonds (C≡C): Three pairs of electrons shared (bond length: 120 pm; bond energy: 823 kJ/mol)

As the number of shared electron pairs increases, bond length decreases and bond strength increases, significantly affecting molecular properties and reactivity.

Allotropes of Carbon

Carbon exists in three primary crystalline allotropic forms, each with distinct physical properties resulting from different atomic arrangements:

Diamond

Diamond features a three-dimensional tetrahedral network where each carbon atom bonds to four others through strong covalent bonds extending throughout the crystal. This rigid structure makes diamond the hardest naturally occurring substance, with exceptional properties:

- Extreme hardness: Used in cutting tools, drilling equipment, and abrasives

- High melting point: 3930°C (4203 K) due to strong covalent bonding

- Electrical insulator: All valence electrons participate in bonding; none remain free

- High thermal conductivity: Despite being an electrical insulator

- Optical properties: High refractive index (2.42) creates brilliant light dispersion

Graphite

Graphite's structure consists of parallel layers of hexagonally arranged carbon atoms. Within each layer, carbon atoms form strong covalent bonds with three neighbors, while the fourth valence electron delocalizes across the layer. Weak van der Waals forces hold the layers together, conferring unique properties:

- Softness and lubricity: Layers slide easily over one another

- Electrical conductivity: Delocalized electrons move freely within layers

- Lower density: Wide interlayer spacing (340 pm) compared to diamond

- High melting point: Strong in-plane bonding requires substantial energy to break

Applications include: Lubricants for high-temperature machinery, pencil leads, electrodes in batteries, and moderators in nuclear reactors.

Fullerenes

Discovered in 1985, fullerenes represent the newest carbon allotrope family. The most famous member, Buckminsterfullerene (C₆₀), contains 60 carbon atoms arranged in a soccer ball-like structure with 20 hexagonal and 12 pentagonal faces. These molecules offer exciting technological possibilities:

- Superconducting materials

- Semiconductor applications

- High-strength construction fibers

- Potential drug delivery systems

- Catalytic applications

Hydrocarbons: The Foundation of Organic Chemistry

Hydrocarbons compounds containing only carbon and hydrogen serve as parent compounds for all other organic molecules. They classify into two major categories:

Saturated Hydrocarbons (Alkanes)

Alkanes contain only single carbon-carbon and carbon-hydrogen bonds, represented by the general formula CₙH₂ₙ₊₂. The prefix indicates carbon atom count (meth- for 1, eth- for 2, prop- for 3), while the suffix "-ane" denotes saturation.

Examples:

- Methane (CH₄): Natural gas component, simplest alkane

- Ethane (C₂H₆): Found in petroleum gas

- Propane (C₃H₈): LPG component

- Butane (C₄H₁₀): Lighter fuel and aerosol propellant

Alkanes exhibit relatively low reactivity due to stable C-C and C-H bonds, though they undergo substitution reactions under specific conditions (e.g., halogenation in sunlight).

Unsaturated Hydrocarbons

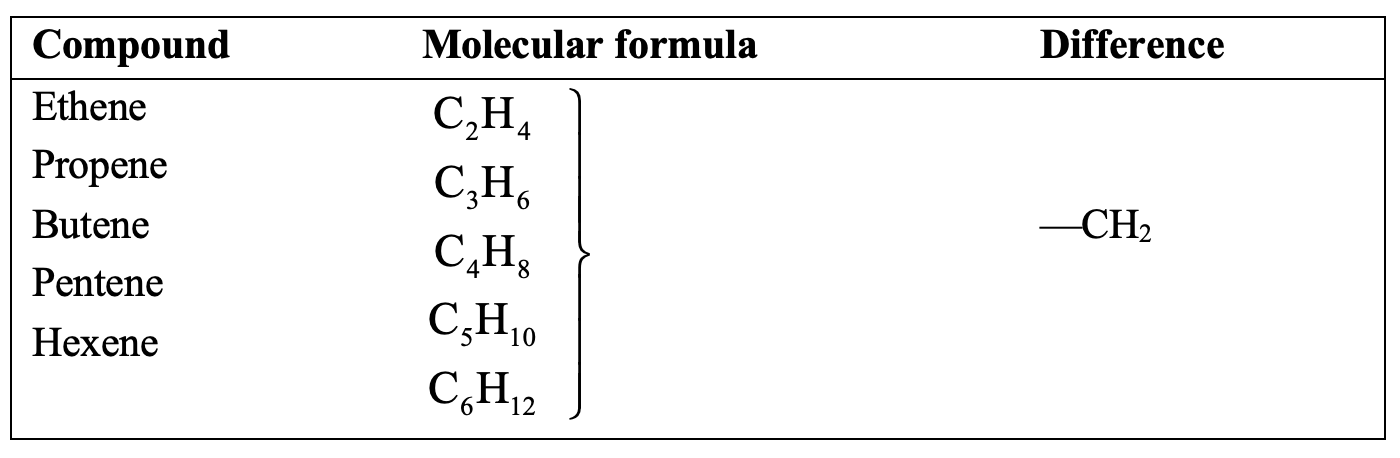

Alkenes (CₙH₂ₙ) contain at least one carbon-carbon double bond, indicated by the suffix "-ene." The presence of π bonds makes alkenes more reactive than alkanes, readily undergoing addition reactions.

Alkynes (CₙH₂ₙ₋₂) feature at least one carbon-carbon triple bond, designated by the suffix "-yne." These compounds exhibit even greater reactivity than alkenes due to multiple π bonds.

The degree of unsaturation significantly impacts physical properties, chemical reactivity, and practical applications. Unsaturated hydrocarbons serve as important industrial starting materials for polymer production, pharmaceuticals, and various chemical syntheses.

Nomenclature of Organic Compounds

Systematic naming follows IUPAC (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry) conventions, ensuring universal chemical communication. The system comprises three components:

IUPAC Naming Rules

1. Word Root: Indicates the number of carbon atoms in the longest continuous chain

- Meth- (1 carbon)

- Eth- (2 carbons)

- Prop- (3 carbons)

- But- (4 carbons)

- Pent- (5 carbons)

- Hex- (6 carbons)

2. Primary Suffix: Denotes saturation or unsaturation

- "-ane" for single bonds (saturated)

- "-ene" for double bonds (unsaturated)

- "-yne" for triple bonds (unsaturated)

3. Secondary Suffix: Indicates functional groups

- "-ol" for alcohols (–OH)

- "-al" for aldehydes (–CHO)

- "-one" for ketones (–CO–)

- "-oic acid" for carboxylic acids (–COOH)

Naming Branched Compounds

For branched hydrocarbons:

- Identify the longest continuous carbon chain

- Number carbon atoms to give substituents the lowest possible numbers

- Name substituents as alkyl groups (methyl-, ethyl-, propyl-)

- Use prefixes di-, tri-, tetra- for multiple identical substituents

- Arrange different substituents alphabetically

Example: 2,4-dimethylhexane indicates a six-carbon chain with methyl groups at positions 2 and 4.

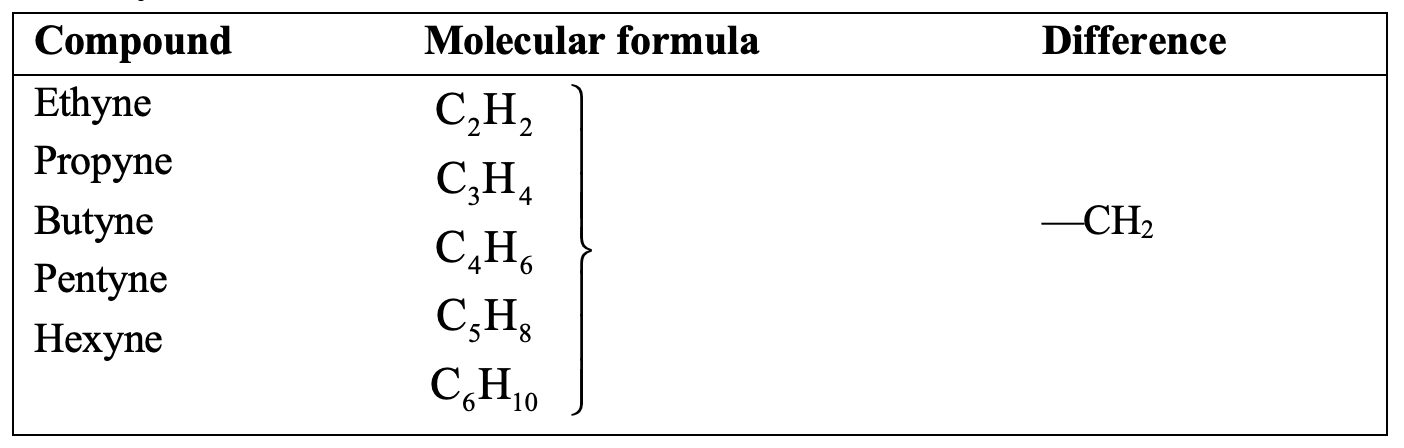

Functional Groups: The Reactive Centers

Functional groups are specific atoms or groups of atoms that determine an organic compound's characteristic chemical properties. These groups represent the reactive portion of molecules, while the carbon skeleton remains relatively inert.

Common Functional Groups

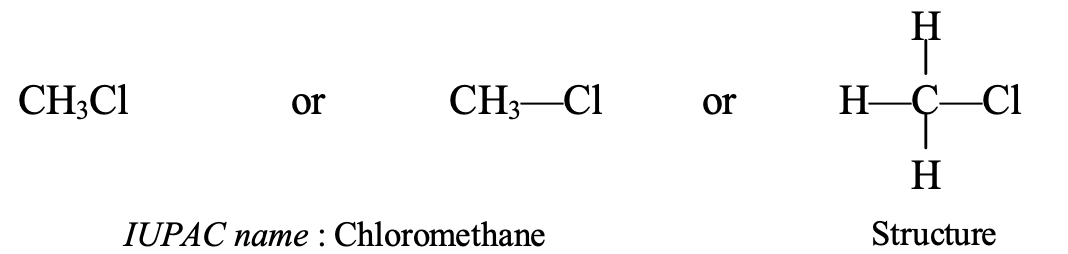

Haloalkanes (R–X): Halogen atoms (F, Cl, Br, I) replace hydrogen

- Example: Chloromethane (CH₃Cl)

- Applications: Solvents, refrigerants, chemical intermediates

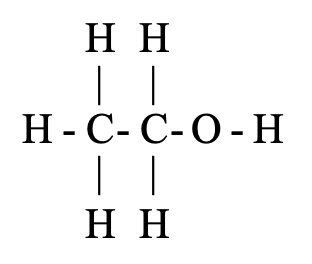

Alcohols (R–OH): Hydroxyl group attached to saturated carbon

- Example: Ethanol (C₂H₅OH)

- Properties: Hydrogen bonding increases boiling point and water solubility

Aldehydes (R–CHO): Carbonyl group at terminal carbon

- Example: Methanal (formaldehyde, HCHO)

- Characteristics: Easily oxidized to carboxylic acids

Ketones (R–CO–R'): Carbonyl group between two carbon atoms

- Example: Propanone (acetone, CH₃COCH₃)

- Minimum three carbons required

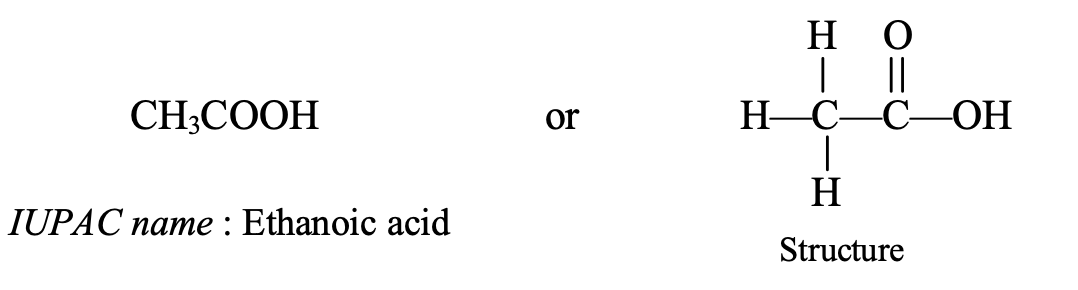

Carboxylic Acids (R–COOH): Carboxyl group combining carbonyl and hydroxyl

- Example: Ethanoic acid (acetic acid, CH₃COOH)

- Properties: Acidic, forms salts with bases

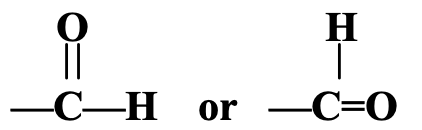

Homologous Series

A homologous series consists of compounds with the same functional group and general formula, where successive members differ by a –CH₂– unit. Members exhibit:

- Similar chemical properties (same functional group)

- Gradual variation in physical properties (melting point, boiling point, density)

- Consistent difference of 14 u (atomic mass units) between adjacent members

- Representation by a common general formula

This systematic organization allows prediction of properties and simplifies the study of organic chemistry's vast compound diversity.

Chemical Reactions of Carbon Compounds

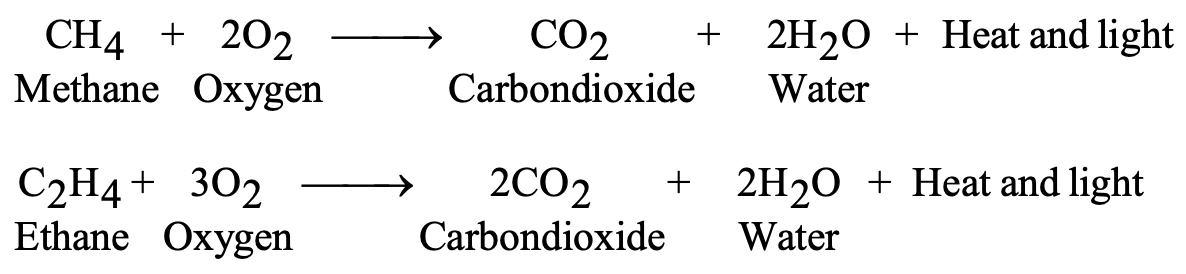

Combustion

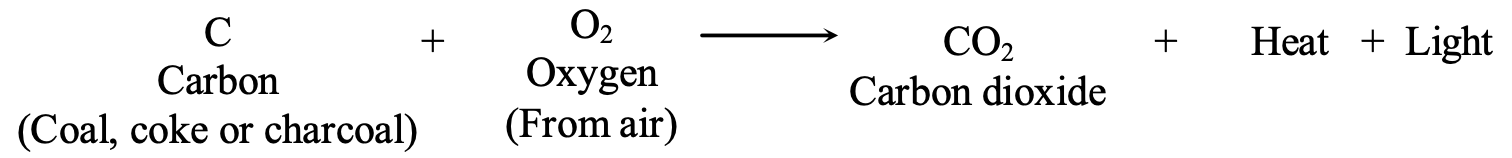

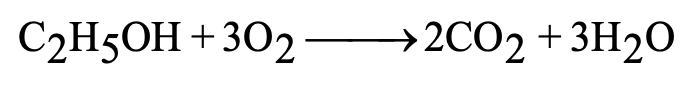

Carbon and its compounds oxidize in oxygen, releasing substantial energy:

Complete combustion produces carbon dioxide and water:

- C + O₂ → CO₂ + Heat + Light

- C₂H₆ + 7/2 O₂ → 2CO₂ + 3H₂O

Incomplete combustion (insufficient oxygen) yields carbon monoxide and soot:

- 2C₂H₆ + 5O₂ → 4CO + 6H₂O

Complete combustion is desired for maximum energy release and minimal pollution. Incomplete combustion wastes fuel, produces toxic carbon monoxide, and generates particulate pollutants.

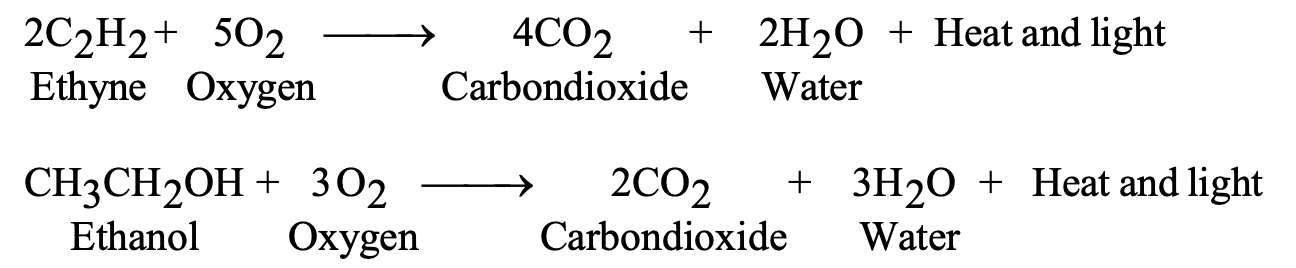

Oxidation

Oxidation involves oxygen addition or hydrogen removal. Strong oxidizing agents like alkaline potassium permanganate (KMnO₄) or acidified potassium dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇) convert:

Alcohols to carboxylic acids: C₂H₅OH + 2[O] → CH₃COOH + H₂O

This reaction demonstrates functional group interconversion, fundamental to organic synthesis.

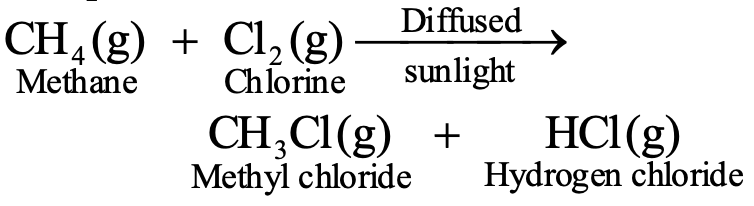

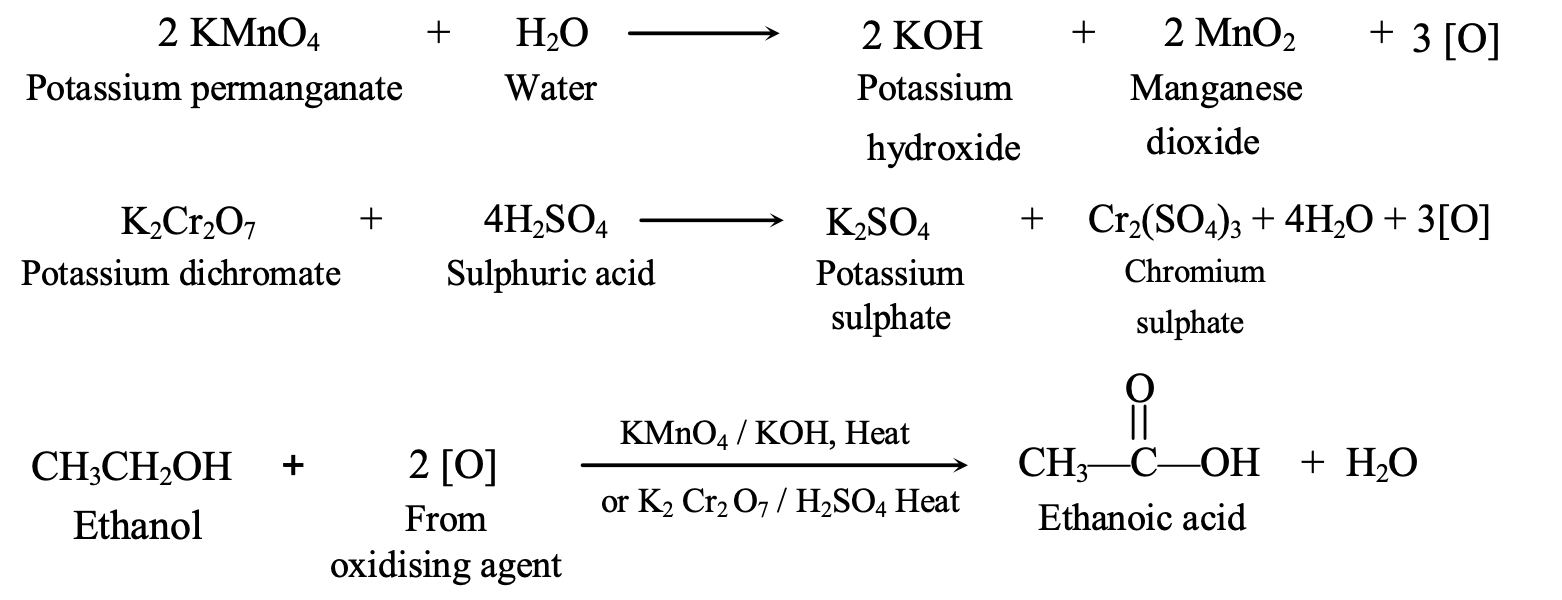

Substitution Reactions

Saturated compounds undergo substitution, where one atom/group replaces another:

Halogenation of methane (requires sunlight): CH₄ + Cl₂ → CH₃Cl + HCl

Successive substitution can replace all hydrogen atoms: CH₃Cl + Cl₂ → CH₂Cl₂ + HCl → CHCl₃ + HCl → CCl₄ + HCl

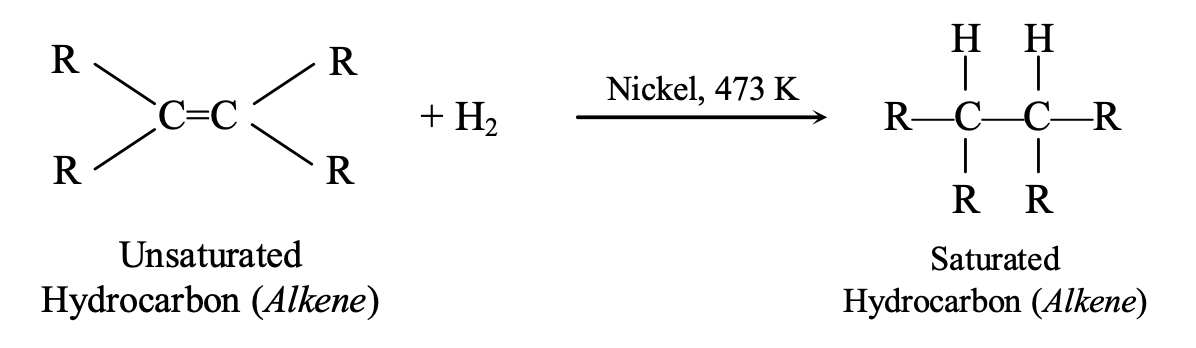

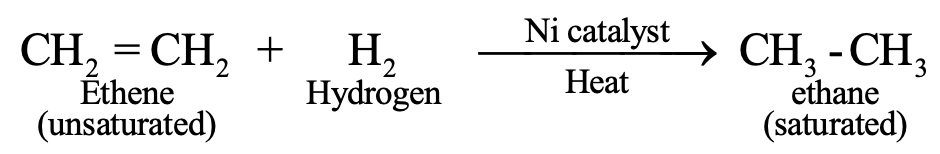

Addition Reactions

Unsaturated compounds add atoms across multiple bonds:

Hydrogenation (catalytic addition of hydrogen): C₂H₄ + H₂ → C₂H₆ (with Ni catalyst at 473 K)

This process converts unsaturated vegetable oils into saturated fats (vanaspati ghee), though excessive consumption of saturated fats poses health risks.

Halogen addition: C₂H₄ + Br₂ → C₂H₄Br₂

These reactions test for unsaturation, as addition causes bromine's brown color to disappear.

Important Carbon Compounds

Ethanol (C₂H₅OH)

Ethanol, the second member of the alcohol homologous series, plays crucial roles in industry, medicine, and daily life.

Physical Properties:

- Colorless liquid with pleasant odor

- Boiling point: 351 K (78°C)

- Miscible with water in all proportions

- Neutral to litmus

Chemical Reactions:

Combustion: C₂H₅OH + 3O₂ → 2CO₂ + 3H₂O + Heat

Oxidation: C₂H₅OH + [O] → CH₃CHO + [O] → CH₃COOH

Reaction with sodium: 2C₂H₅OH + 2Na → 2C₂H₅ONa + H₂

Esterification: CH₃COOH + C₂H₅OH ⇌ CH₃COOC₂H₅ + H₂O

Uses:

- Alcoholic beverages (beer ~4%, wine ~12%, whisky ~40%)

- Medical sterilization and antiseptics

- Solvent in pharmaceutical tinctures

- Antifreeze solutions

- Chemical manufacturing (plastics, perfumes, medicines)

Safety Note: Consuming methanol-contaminated ethanol causes severe poisoning, blindness, and potentially death. Industrial alcohol is denatured with toxic additives to prevent misuse.

Ethanoic Acid (CH₃COOH)

Commonly known as acetic acid or vinegar (5-8% solution), ethanoic acid is a fundamental carboxylic acid.

Physical Properties:

- Colorless, viscous liquid

- Pungent, irritating odor

- Boiling point: 391 K (118°C)

- Melting point: 290 K (17°C)—freezes in winter (glacial acetic acid)

- Miscible with water, alcohol, ether

Chemical Properties:

Acid-base reactions: CH₃COOH + NaOH → CH₃COONa + H₂O 2CH₃COOH + Na₂CO₃ → 2CH₃COONa + H₂O + CO₂

Metal reactions: 2CH₃COOH + 2Na → 2CH₃COONa + H₂

Esterification: CH₃COOH + C₂H₅OH ⇌ CH₃COOC₂H₅ + H₂O (with conc. H₂SO₄ catalyst)

Uses:

- Food preservation (pickles, sauces)

- Manufacturing cellulose acetate (photographic film, rayon)

- Synthetic fiber production

- Paint and dye industries

- Chemical synthesis intermediate

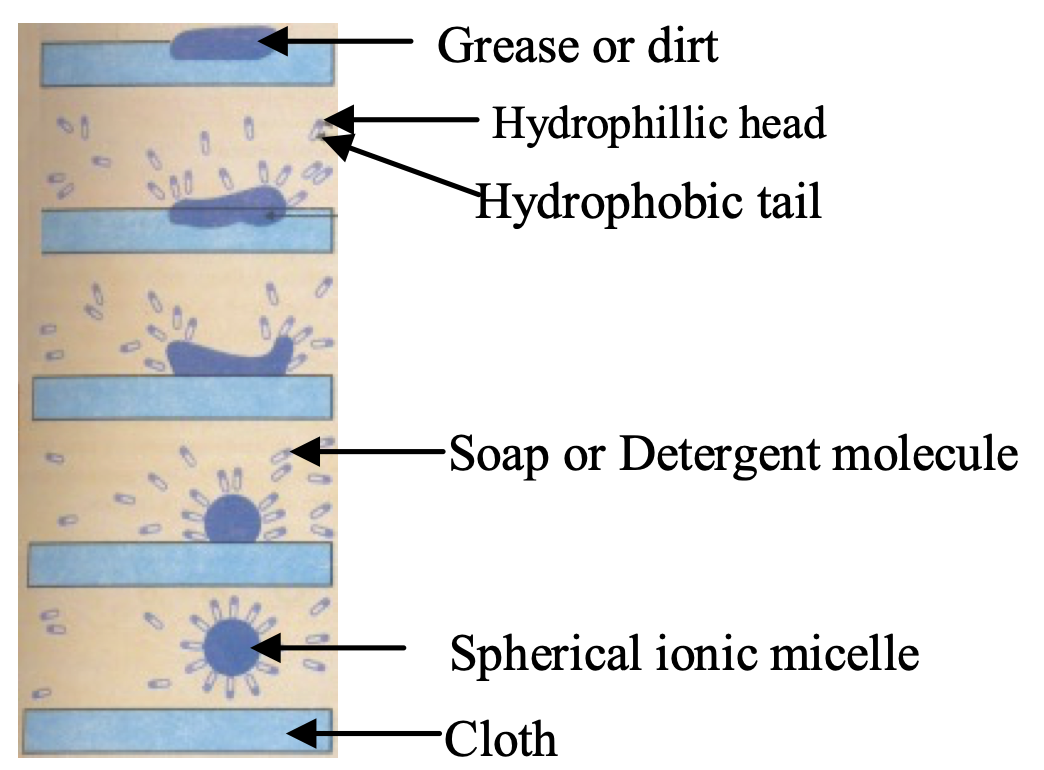

Soaps and Detergents

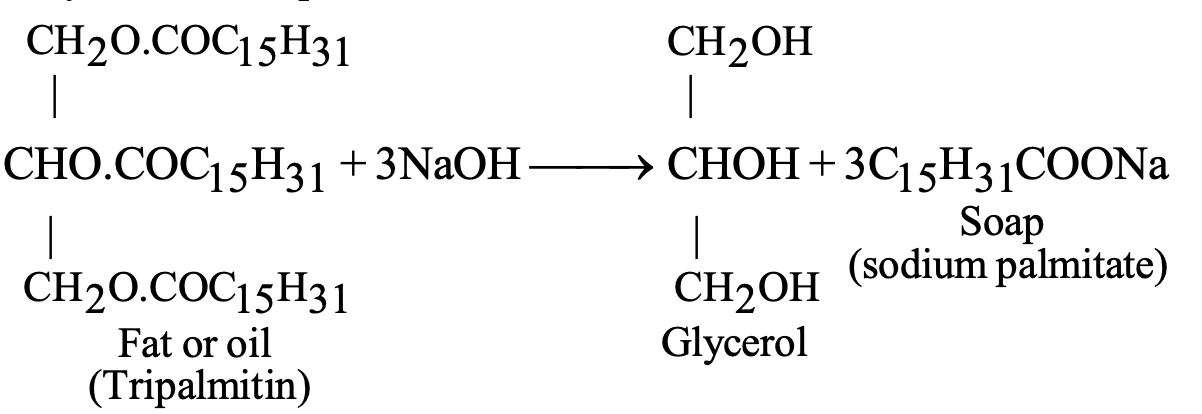

Soaps are sodium or potassium salts of long-chain fatty acids (carboxylic acids), prepared through saponification alkaline hydrolysis of fats:

Fat + 3NaOH → Glycerol + 3(Soap molecules)

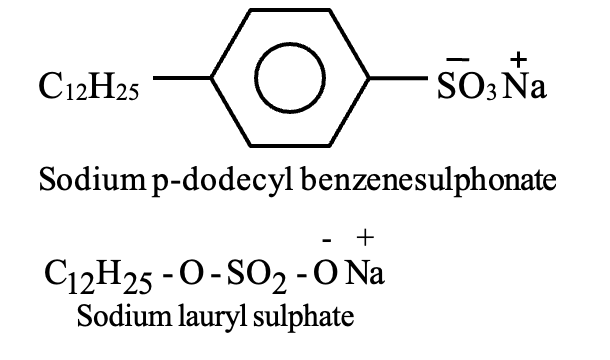

Soap molecules contain:

- Hydrophobic tail: Long hydrocarbon chain (water-repelling)

- Hydrophilic head: Ionic –COO⁻Na⁺ group (water-attracting)

This dual nature enables soaps to emulsify oils and grease, allowing removal by water.

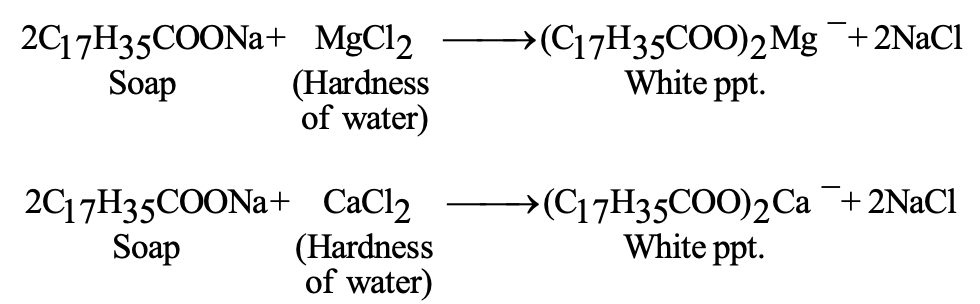

Limitation: Soaps form insoluble precipitates with calcium and magnesium ions in hard water: 2C₁₇H₃₅COONa + CaCl₂ → (C₁₇H₃₅COO)₂Ca + 2NaCl

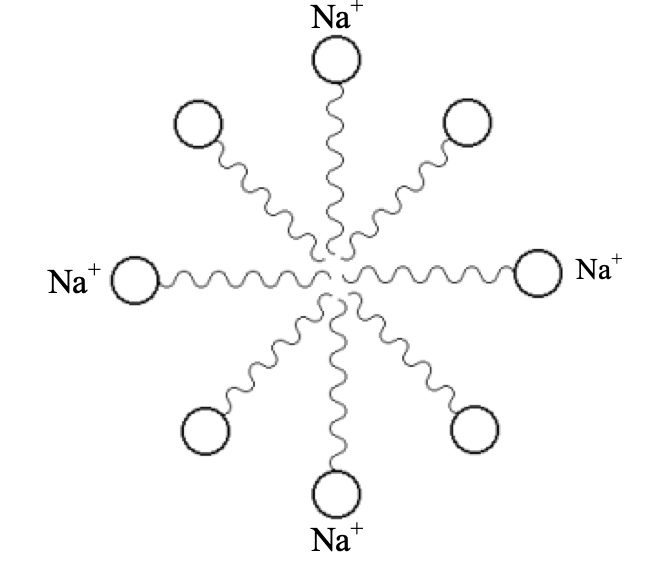

Detergents (synthetic soaps) are sodium salts of long-chain benzene sulfonic acids or alkyl hydrogen sulfates. They offer advantages over traditional soaps:

- Effective in hard water (form soluble calcium/magnesium salts)

- Superior cleaning in acidic conditions

- Better solubility across temperature ranges

However, early detergents caused environmental problems due to non-biodegradable components. Modern detergents use biodegradable alkyl chains to minimize ecological impact.

Key Chemical Formulas Reference Table

| Compound Type | General Formula | Example | IUPAC Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkanes (saturated) | CₙH₂ₙ₊₂ | CH₄ | Methane |

| Alkenes (one C=C) | CₙH₂ₙ | C₂H₄ | Ethene |

| Alkynes (one C≡C) | CₙH₂ₙ₋₂ | C₂H₂ | Ethyne |

| Alcohols | R–OH | C₂H₅OH | Ethanol |

| Aldehydes | R–CHO | CH₃CHO | Ethanal |

| Ketones | R–CO–R' | CH₃COCH₃ | Propanone |

| Carboxylic Acids | R–COOH | CH₃COOH | Ethanoic acid |

| Haloalkanes | R–X | CH₃Cl | Chloromethane |

Important Reaction Equations

| Reaction Type | Equation | Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Complete combustion | C₂H₆ + 7/2 O₂ → 2CO₂ + 3H₂O | Sufficient oxygen |

| Alcohol oxidation | C₂H₅OH + 2[O] → CH₃COOH + H₂O | KMnO₄ or K₂Cr₂O₇ |

| Esterification | CH₃COOH + C₂H₅OH ⇌ CH₃COOC₂H₅ + H₂O | Conc. H₂SO₄, heat |

| Saponification | Fat + 3NaOH → Glycerol + 3RCOONa | Heat, alkaline medium |

| Hydrogenation | C₂H₄ + H₂ → C₂H₆ | Ni catalyst, 473 K |

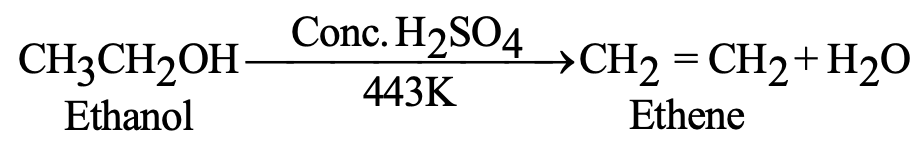

| Dehydration | C₂H₅OH → C₂H₄ + H₂O | Conc. H₂SO₄, 443 K |

Fossil Fuels: Coal and Petroleum

Fossil fuels coal, petroleum, and natural gas represent prehistoric biological materials transformed under heat and pressure over millions of years.

Coal Formation

Coal originated from land plants and trees buried beneath Earth's surface approximately 300 million years ago. Geological processes (high temperature, pressure, absence of oxygen) converted organic matter through stages:

Peat → Lignite → Bituminous coal → Anthracite

Each stage increases carbon content while decreasing volatile matter and moisture.

Petroleum Formation

Petroleum formed from microscopic marine organisms (plankton) that died and settled on ancient sea floors. Sediment layers buried these remains, and anaerobic decomposition under specific temperature-pressure conditions produced crude oil and natural gas.

Petroleum composition: Complex mixture of hydrocarbons (alkanes, cycloalkanes, aromatic compounds)

Refining process: Fractional distillation separates petroleum into useful fractions:

- Petroleum gas (C₁–C₄): LPG, fuel

- Petrol/gasoline (C₅–C₉): Vehicle fuel

- Kerosene (C₁₀–C₁₆): Jet fuel, heating

- Diesel (C₁₅–C₁₈): Heavy vehicle fuel

- Lubricating oil (C₁₉–C₃₅): Machinery lubrication

- Bitumen (>C₃₅): Road surfacing

Environmental Considerations

Burning fossil fuels releases carbon dioxide (greenhouse gas) and other pollutants (sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, particulates), contributing to climate change, acid rain, and respiratory problems. Sustainable alternatives—renewable energy sources—increasingly supplement or replace fossil fuels.

Conclusion

Carbon's unique properties tetravalency, catenation, and versatile bonding—underpin the extraordinary diversity of organic chemistry. From simple hydrocarbons to complex biological macromolecules, carbon compounds form the molecular foundation of life and modern technology. Understanding carbon compound nomenclature, structure, properties, and reactions provides essential knowledge for students pursuing chemistry and related sciences. This comprehensive treatment aligns with NTSE curriculum requirements while offering practical insights into carbon chemistry's role in daily life, industry, and environmental science.

For NTSE aspirants: Master the systematic nomenclature, functional group recognition, reaction mechanisms, and key compound properties. Practice structure-property correlations and equation balancing. Remember that organic chemistry builds systematically—each concept connects to previous learning, creating an integrated understanding essential for competitive examinations and future scientific study.

ORGANIC COMPOUNDS

The compounds like urea, sugars, fats, oils, dyes, proteins, vitamins etc., which were isolated directly or indirectly from living organisms such as animals and plants were called organic compounds. The branch of chemistry which deals with the study of these compounds is called Organic Chemistry.

CARBON

|

Carbon is a non-metallic element. Chemical symbol : C Symbolic Representation : 126C Where, atomic number is 6 and atomic mass is 12 Therefore, it has Number of protons = 6 Number of neutrons = 6 Number of electrons = 6 Electronic configuration : K = 2 L = 4 Valence electrons = 4 Valency = 4 |

|

TYPES OF CHEMICAL BONDS

There are two types of chemical bonds:

(i) Ionic bond

(ii) Covalent bond.

IONIC BOND:

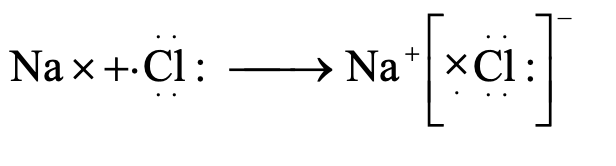

The chemical bond formed by the complete transfer of electrons from one atom to another is known as an ionic bond. The transfer of electrons takes place in such a way that the ions formed have the stable electron arrangement of an inert gas i.e. 8 electrons in the outermost shell (octet). The ionic bond is called so because it is a chemical bond between oppositely charged ions i.e. one positive and one negative ion.

When a metal reacts with a non-metal, transfer of electrons takes place from metal atoms to the non-metal atoms, and an ionic bond is formed.

The compounds containing ionic bonds are called ionic compounds. Ionic compounds are made up of ions. Lets understand it with the help of an example.

Formation of Sodium Chloride:

Atomic number of sodium (Na) = 11

∴ Its electronic configuration is 2, 8, 1.

It has only one electron in the valence shell. It loses this electron to acquire the stable electronic configuration 2, 8 (similar to that of neon) and form sodium ion (Na+).

Na^× → Na^+ + e^−

Sodium atom → Sodium ion

(2, 8, 1) → (2, 8)

Atomic number of chlorine (Cl) = 17

∴ Its electronic configuration is 2, 8, 7.

It has seven electrons in the valence shell. It gains one electron to acquire the stable electronic configuration 2, 8, 8 (similar to that of argon) and form chloride ion (Cl^−).

:Ċl: + e^− → [:Ċl:]^−

Chlorine atom → Chloride ion

(2, 8, 7) → (2, 8, 8)

Thus, when a sodium atom and a chlorine atom approach each other, an electron is transferred from sodium atom to chlorine atom. In other words, sodium loses one electron to form Na+ ion and chlorine gains that electron to form Cl− ion. As a result, both acquire the stable nearest noble gas configuration. These oppositely charged ions are then held together by electrostatic forces of attraction forming the compound Na+Cl− or simply written as NaCl. The transfer of electron may be represented in one step as follows:

Na+ + :Ċl: → Na+ [:Ċl:]− or NaCl

Sodium atom Chlorine atom → Sodium chloride

(2, 8, 1) + (2, 8, 7) → (2, 8, 7)

Note: The dots (·) and crosses (×) in the image represent electrons from different atoms, and the curved arrow shows the transfer of an electron from sodium to chlorine.

THE COVALENT BOND:

Most carbon compounds are poor conductors of electricity. The boiling and melting points of the carbon compounds are low. Forces of attraction between these molecules of organic compounds are not very strong. As these compounds are largely non conductors of electricity hence the bonding in these compounds does not give rise to any ions.

The reactivity of elements is explained as their tendency to attain a completely filled outer shell, that is, attain noble gas configuration. Element forming ionic compounds achieve this by either gaining or losing electrons from the outermost shell. In the case of carbon, it has four electrons in its outermost shell and needs to gain or lose four electrons to attain noble gas configuration. If it were to gain or lose electrons-

(i) It could gain four electrons forming C4– anion. But it would be difficult for the nucleus with six protons to hold on to ten electrons, that is, four extra electrons.

(ii) It could lose four electrons forming C4+ cation. But it would require a large amount of energy to remove four electrons leaving behind a carbon cation with six protons in its nucleus holding on to just two electrons.

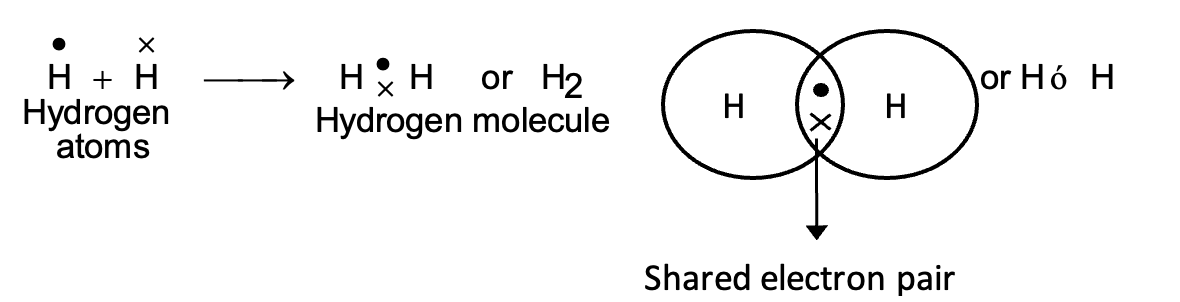

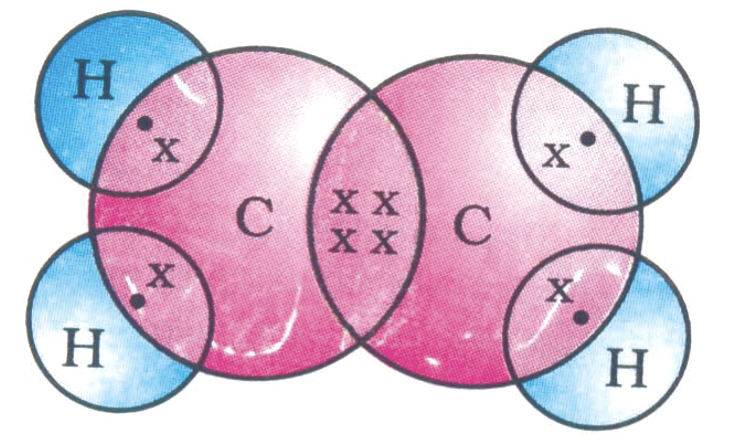

Carbon overcomes this problem by sharing its valence electrons with other atoms of carbon or with atoms of other elements. The shared electrons belong to the outer shell of both the atoms and lead to both atoms attaining the noble gas configuration.

Some simple molecules formed by the sharing of Valence electrons are as follows-

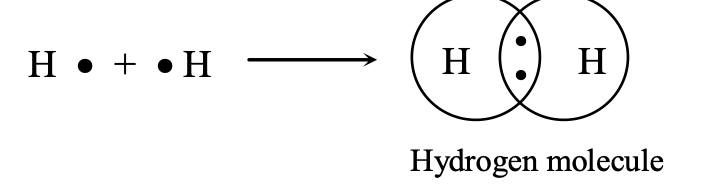

(i) Hydrogen Molecule:

This is the simplest molecule formed by sharing of electrons. The atomic number of hydrogen is 1 and it has only one electron in its outermost K shell. It requires only one more electron to complete the K shell. So, when two hydrogen atoms approach each other, the single electron of both the atoms forms a shared pair. This may be represented as:

According to Lewis notation, the electrons in the valence shell are represented by dots and crosses. This method was proposed by G.N. Lewis and is known as Lewis representation or Lewis structure. The shared pair of electron (shown x) is said to constitute a single bond between the two hydrogen atoms and is represented by a line between the two atoms. Pictorially, the molecule can be represented by drawing two overlapping circles around the symbols of the atoms and showing the shared pair of electrons in the overlapping part.

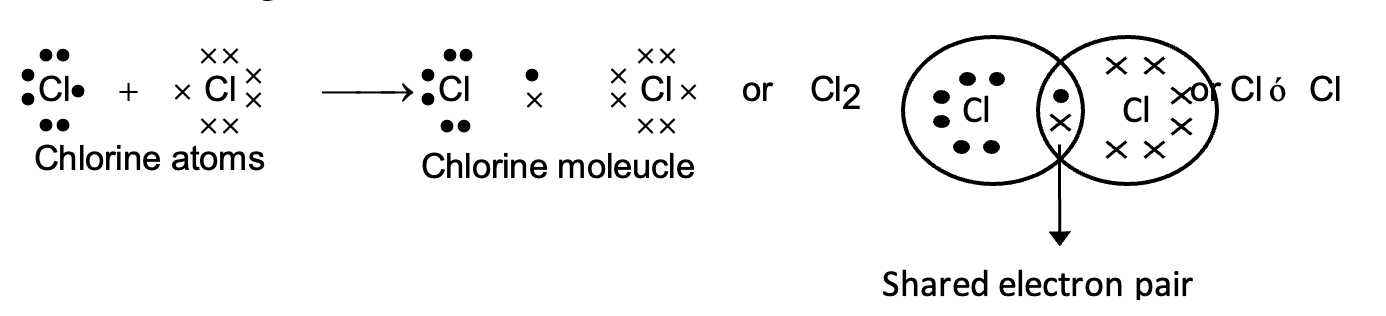

(ii) Chlorine molecule:

Each chlorine atom has seven electrons its outermost shell. When the two chlorine atoms come close together, an electron of both the atoms is shared between them.

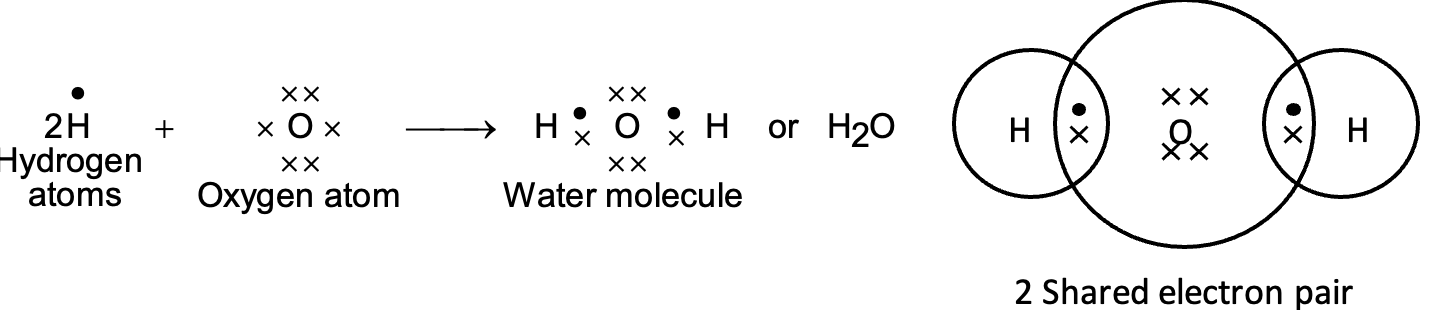

(iii) Formation of water molecule (H2O):

Each hydrogen atom has only one electron in its outermost shell. Therefore, each hydrogen atom requires one more electron to achieve the stable configuration of helium (nearest noble gas). The oxygen atom has the electronic configuration (2, 6) and has six electrons in its outermost shell. It needs two electrons to complete its octet. Therefore, one atom of oxygen shares its electron with two hydrogen atoms.

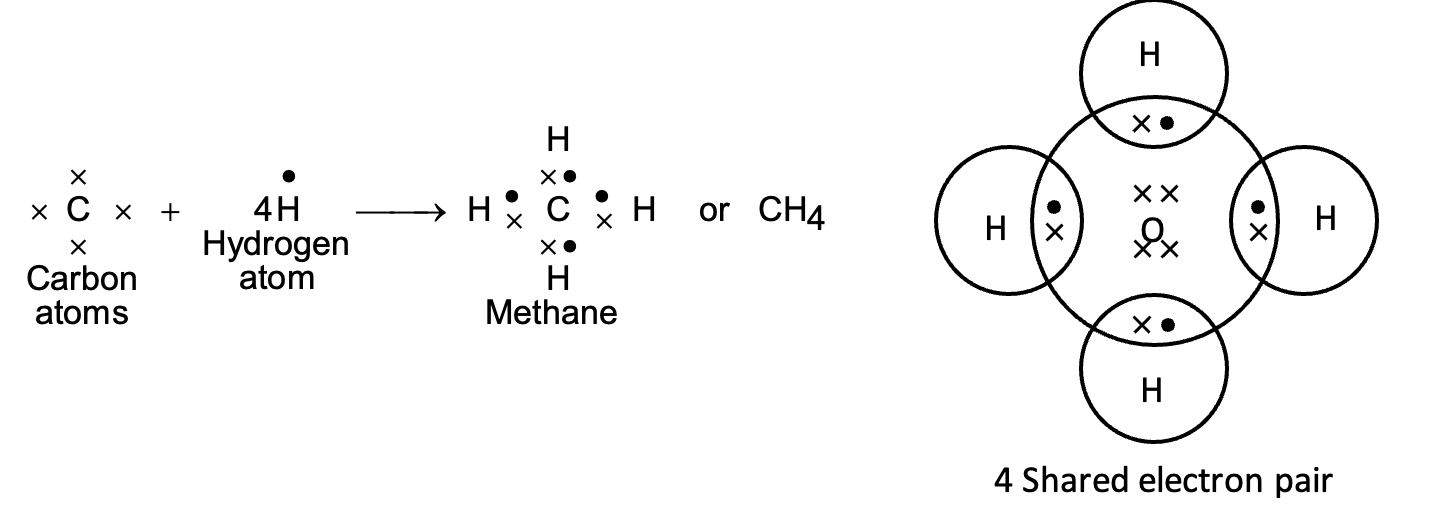

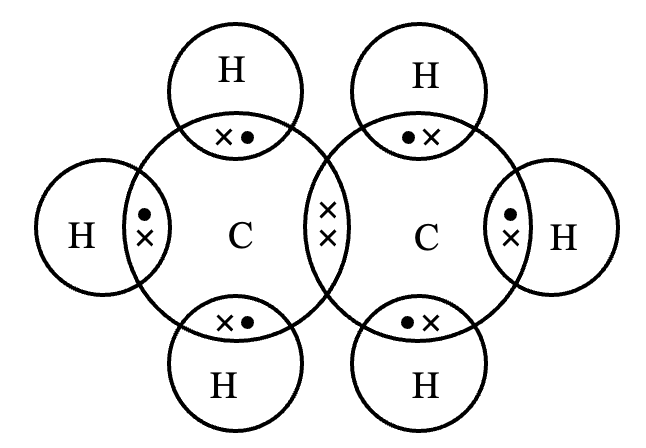

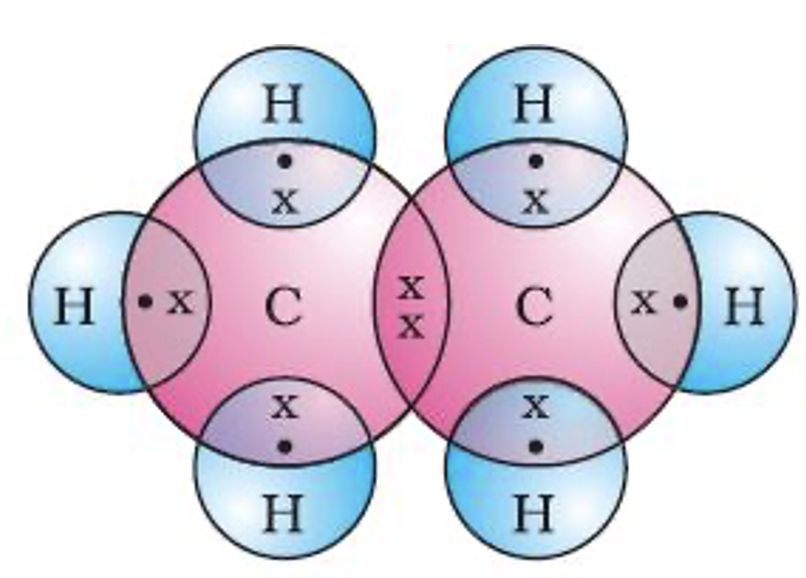

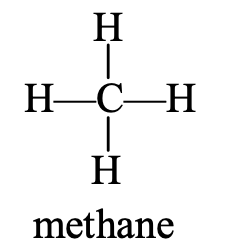

(iv) Formation of methane molecule (CH4):

Methane (CH4) is a covalent compound containing covalent bonds. Carbon atom has atomic number 6. Its electronic configuration is (2, 4). It has four electrons in its valence shell and needs 4 more electrons to get the stable noble gas configuration. Hydrogen atom has one electron and needs one more electron to get stable electronic configuration of nearest noble gas, helium. Therefore, one atom of carbon shares its four electrons with four atoms of hydrogen to form four covalent bonds.

Different kinds of Covalent Bonds:

Electron pair shared between two atoms results in the formation of a covalent bond. This shared pair is also called bonding pair of electron.

- If two atoms share one electron pair, bond is known as single covalent bond and is represented by one dash (-).

- If two atoms share two electron pairs, bond is known as double covalent bond and is represented by two dashes (- -).

- If two atoms share three electron pairs, bond is known as triple covalent bond and is represented by three dashes (- - -).

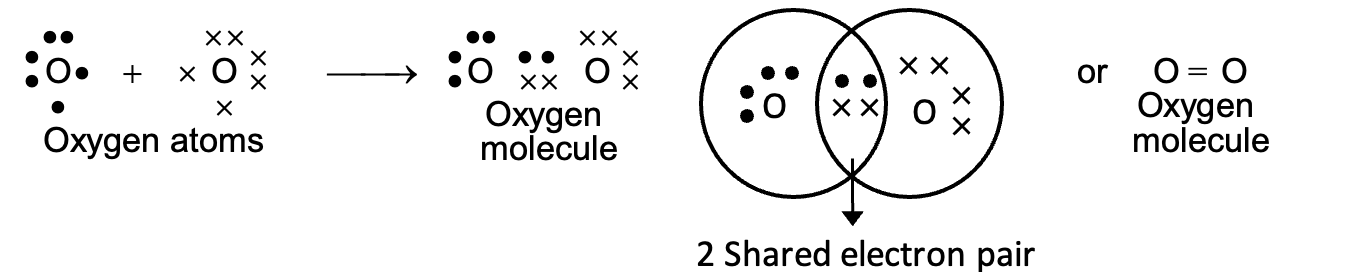

(i) Formation of double bond (oxygen molecule):

Two oxygen atoms combine to form oxygen molecule by sharing two electron pairs. Each oxygen atom (2, 6) has six electrons in the valence shell. It requires two electrons to acquire nearest noble gas configuration. Therefore, both the atoms contribute two electrons each for sharing to form oxygen molecule. In the molecule, two electron pairs are shared and hence there is a double bond between the oxygen atoms.

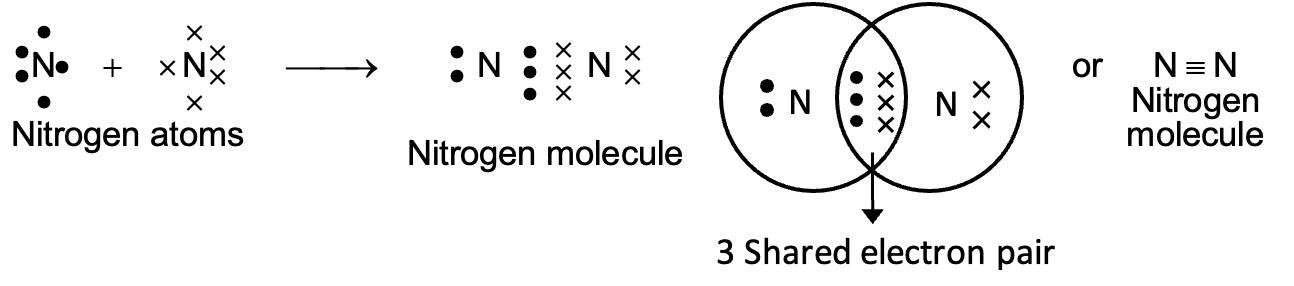

(ii) Formation of triple bond (Nitrogen molecule):

Nitrogen atom has five electrons in its valence shell. In the formation of a nitrogen molecule, each of the following atoms provides three electrons to form three electron pairs for sharing. Thus, a triple bond is formed between two nitrogen atoms.

Characteristic Properties of Covalent Compounds:

The important characteristic properties of covalent compounds are:

(i) Covalent compounds consist of molecules:

The covalent compounds consist of molecules. They do not have ions. For example – hydrogen gas, oxygen gas, nitrogen gas etc. consist of H2, O2 and N2 molecules respectively.

(ii) Physical state:

Weak Vanderwaal forces are present between the molecules of covalent compounds. So, covalent compounds are in gaseous or liquid state at normal temperature and pressure. For example: Hydrogen, chlorine, methane, oxygen, nitrogen are gases while carbon tetrachloride, ethyl alcohol, ether, bromine etc. are liquids. Glucose, sugar, urea, iodine etc. are some solid covalent compounds.

(iii) Crystal structure

Covalent compounds exhibit both crystalline and non crystalline structure.

(iv) Melting point and Boiling point:

Energy required to break the crystal is less due to the presence of weak Vanderwaal force, so their melting and boiling points are less.

(v) Electrical conductivity:

Covalent compounds are bad conductors of electricity due to the absence of free electrons or free ions.

(vi) Solubility:

Due to the non - polar nature of covalent compounds they are soluble in non - polar solvents like benzene, carbon tetrachloride etc. and insoluble in polar solvents like water etc.

COMPARISON OF PROPERTIES OF IONIC AND COVALENT COMPOUNDS:

Some main points of difference are given in the following table:

|

1.Mode of formation. They are formed by complete transfer of electrons from one atom to the other. For example,

Thus, electrovalent compounds consist of ions. |

1. Mode of formation. They are formed by mutual sharing of electrons between the two atoms. For example.

Thus, covalent compounds consist of molecules. |

|

2. Physical state. Ionic compounds are generally solids. For example, NaCl (Sodium chloride), MgO (Magnesium oxide), Na2O (Sodium oxide), MgCl2 (Magnesium chloride), etc. |

2.Physical state. These compounds may be solids, liquids and gases. For example, Cl2 (chlorine) is a gas, Br2 (bromine) is a liquid while I2 (iodine) is a solid. |

|

3. Melting points and boiling points. Due to strong inter molecular forces of attraction between positive and negative ions, the melting points and boiling points of ionic compounds are quite high. |

3. Melting points and boiling points. Due to weak intermolecular forces of attraction, covalent compounds generally have low melting and boiling points. |

|

4. Solubility. ‘Like dissolves like’ is the general rule of solubility. Thus, ionic compounds being polar are more soluble in polar solvents like water but are insoluble in non-polar or organic solvents such as alcohol, benzene, petrol, ether, chloroform, etc. |

4. Solubility. Covalent compounds being non-polar are generally insoluble in polar solvents like water but are soluble in non-polar or organic solvents like alcohol, benzene, petrol, ether, chloroform, etc. |

|

5. Electrical conductivity. Ionic compounds do not conduct electricity in the solid state but do so in the molten state or in their aqueous solutions. For example, solid sodium chloride does not conduct electricity because Na+ and Cl– ions are strongly attracted by each other. However, In molten state NaCl splits to form Na+ and Cl– ions. Similarly, In water, sodium chloride ionizes to form Na+ (aq) and Cl– (aq). Since ions carry current, therefore, sodium chloride conducts electricity both in the molten state as well as in the aqueous solution. |

5. Electrical conductivity. Covalent compounds do not contain ions and hence are generally bad conductors of electricity. |

|

6. Nature of reactions. Ionic compounds undergo ionic reactions which are very fast, almost instantaneous and always proceed to completion. For example, AgNO3 (aq) + NaCl (aq) Silver nitrate Sodium chloride AgCl (s) + NaNO3 (aq) Silver chloride Sodium nitrate (white ppt.) |

6. Nature of reactions. Covalent compounds undergo molecular reactions which are slow and never proceed to completion. For example, |

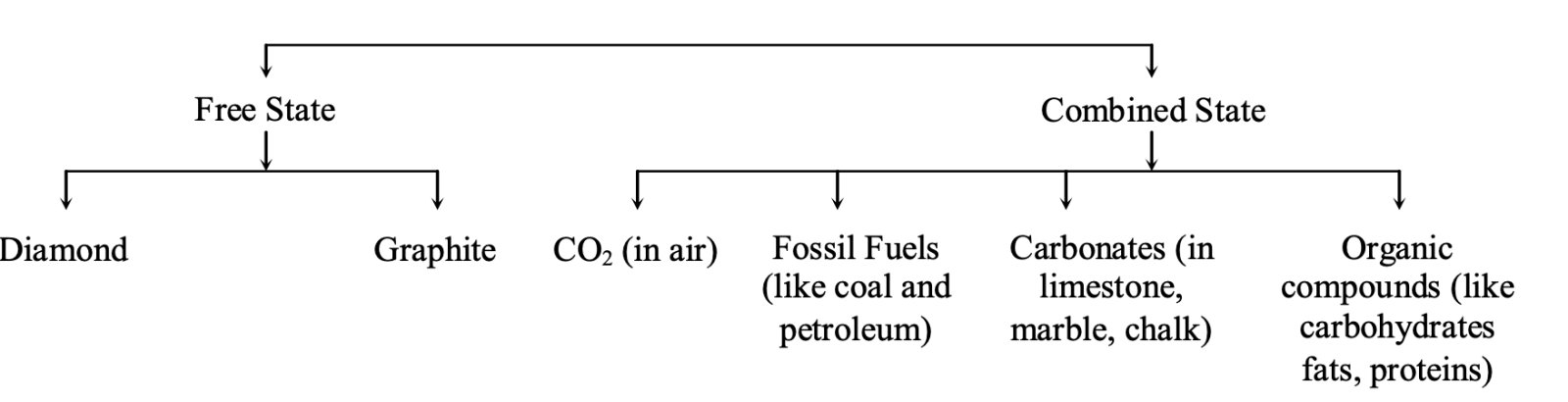

Occurance of Carbon

Allotropes of Carbon

The phenomenon of existence of an element in two or more forms which have different physical properties but identical chemical properties is called allotropy and the different forms are called allotropic forms or simply allotropes.

Carbon occurs in three crystalline allotropic forms. These are :

- Diamond

- Graphite

- Fullerenes

Note: The physical properties of these three allotropes of carbon are, however, different due to different arrangement of carbon atoms in them.

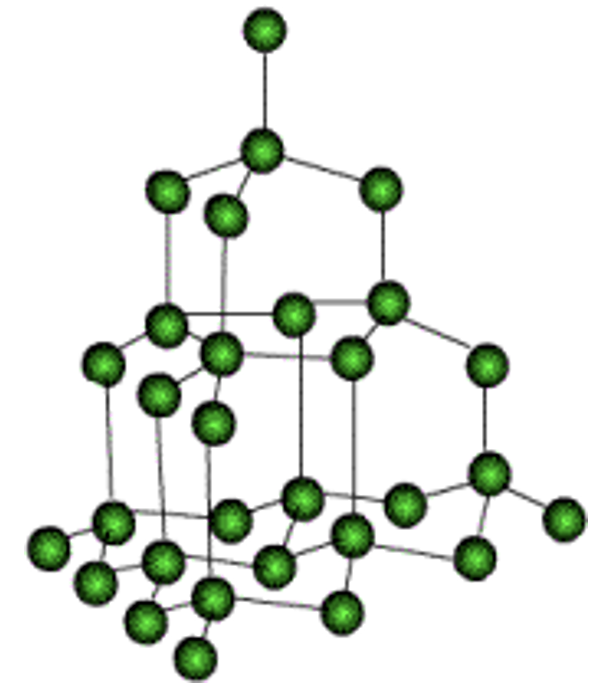

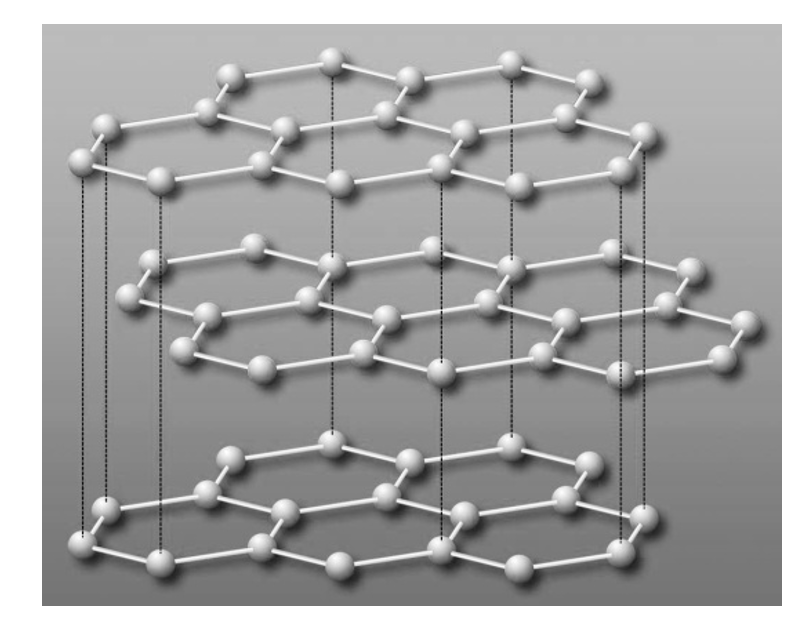

Diamond:

Occurrence: Although diamonds occur in nature, They have also been synthesized by subjecting pure carbon to very high pressure (50,000 – 60,000 atmospheres) and high temperature (1873 K). The synthetic diamonds are small in size but are otherwise indistinguishable from natural diamonds.

Structure of Diamond:

Diamond crystals found in nature are generally octahedral (eight faced). In the structure of diamond, each carbon is linked to four other carbon atoms forming a regular and tetrahedral arrangement and this network of carbon atoms extends in three dimensions and is very rigid. This strong bonding is the cause of its hardness and its high density. This regular, symmetrical arrangement makes the structure very difficult to break. To separate one carbon atom from the structure, we have to break four strong covalent bonds.

Elements in which atoms are bonded covalently found in solid state.

e.g. diamond, graphite, sulphur etc.

Physical Properties:

(i) Hardness: The three-dimensional network structure of diamond makes it the hardest natural substance known. It is because of this hardness, diamond is used for drilling, grinding and polishing equipments like rock borers, glass cutters, dies, etc.

(ii) High density: Due to network structure, the carbon atoms in diamond are closely packed and hence diamond has a high density.

(iii) High melting point: A large amount of energy is needed to break the network structure of diamond. Therefore, the melting point of diamond is quite high (3930°C or 4203 K).

(iv) Electrical and Thermal conductivity: Since all the four valence electrons are firmly held in carbon-carbon single bonds, there are no free electrons in a diamond crystal. Therefore, diamond is a bad conductor of electricity.

(v) Transparency: Because of high refractive index (2.42), diamonds can reflect and refract light. As a result, diamonds are transparent substances.

Uses of Diamond:

(a) They are used in jewellery because of their ability to reflect and refract light.

(b) Diamonds are used in cutting glass and drilling rocks.

(c) Diamond has an extraordinary sensitivity to hot rays and due to this reason, it is used for making high precision thermometers.

(d) Diamond has the ability to cut out harmful radiations and due to this reason it is used for making protective windows for space probes.

(e) Diamond dies are used for drawing thin wires. Very thin tungsten wires of diameter less than one-sixth of the diameter of human hair have been drawn using diamond dies.

(f) Surgeons use diamond knives for performing delicate operations.

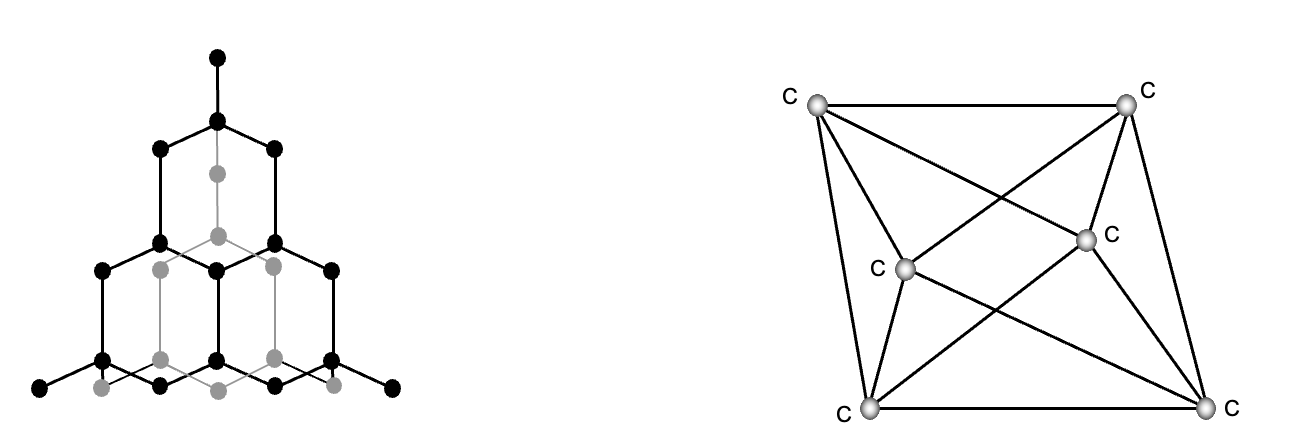

Graphite:

Occurrence: Graphite is a grayish black substance. It occurs in nature mixed with mica, quartz and silica. It is also prepared artificially from carbon in an electric furnace at 2273–2773 K.

Structure of Graphite:

Each carbon is bonded to only three neighboring carbon atoms in the same plane forming layers of hexagonal networks separated by comparatively larger distance. The different layers are held together by weak forces, called vanderwaal forces. The layers can therefore, easily slide over one another. This makes graphite lubricating, soft and greasy to touch.

Within each layer of graphite, every carbon atom is joined to three others by strong covalent bonds. This forms a pattern of interlocking hexagonal rings. The carbon atoms are difficult to separate from one another. So graphite also has a high melting point.

However, the bonds between the layers are weak. The layers are able to slide easily over one another, rather like pack of cards. This makes graphite soft and slippery. When we write with a pencil, layers of graphite flake off and stick to the paper.

Physical properties:

(i) Low density: Due to wide spacing (340 pm) between the two layers, the carbon atoms in graphite are less closely packed and hence the density of graphite (2.22 g cm–3) is much lower than that of diamond.

(ii) Softness: The various layers of carbon atoms in graphite are held together by weak van der Waals forces of attraction. Therefore, one layer can easily slide over the other. This makes graphite soft and hence a useful dry (solid) lubricant for heavy machinery.

(iii) Electrical and thermal conductivity: Carbon has four valence electrons. But in a graphite crystal, each carbon atom is joined to three other carbon atoms by covalent bonds to form hexagonal rings. Thus, only three valence electrons are used for bond formation and hence the fourth valence electron is free to move. As a result, graphite is a good conductor of heat and electricity.

Use:

(i) Due to its softness, powdered graphite is used either as a solid or dry lubricant or mixed with petroleum jelly as graphite grease. Since graphite is non-volatile, it can also be used as a lubricant for heavy machinery operating at very high temperatures.

(ii) Graphite is soft and black in colour and marks paper black. Mixed with desired quantity of wax or clay, graphite is used for making the cores of lead pencils.

(iii) Being a good conductor of electricity, graphite is used for making electrodes for dry cells and electric accessories. The carbon brushes of electric motors are also made up of graphite.

DIFFERENCE BETWEEN DIAMOND AND GRAPHITE:

Some main points of difference between the properties of diamond and graphite are given below:

|

1. Diamond has a three-dimensional network structure. |

1. Graphite has a two-dimensional sheet like structure consisting of a number of benzene rings fused together. |

|

2. It is the hardest natural substance known. |

2. Graphite is soft and greasy and is used as solid lubricant for heavy machinery operating at high temperatures. |

|

3. It is a bad conductor of electricity but is a very good conductor of heat. Because of hardness and high thermal conductivity, diamond tipped tools do not overheat and hence are extensively used for cutting and drilling purposes. |

3. It is a good conductor of both heat and electricity. Because of high electrical conductivity, graphite is used for making electrodes of battery and arcs. |

|

4. It is a transparent substance with high refractive index. Therefore, it is used for making gemstones and jewellery. |

4. It is an opaque grayish black substance. |

FULLERENES:

Structure:

Fullerene is naturally occurring allotrope of carbon in which 60 carbon atoms are linked to form a stable structure. Previously, only two forms of carbon (diamond and graphite) were known. The third allotrope of carbon, called fullerene, was discovered in 1985 by Robert Curl, Herald Kroto and Richard Smalley.

They correctly suggested the cage structure as shown in the figure and named the molecule Buckminster fullerene after the architect Buckminster Fuller, the inventor of the Geodesic dome, which resembles the molecular structure of C60. Molecules of C60 have a highly symmetrical structure in which 60 carbon atoms are arranged in a closed net with 20 hexagonal faces and 12 pentagonal faces. The pattern is exactly like the design on the surface of a soccer ball. C60 has been found to form in sooting flames when hydrocarbons are burned.

All the fullerenes have even number of atoms, with formulae ranging upto C400 and higher. These materials offer exciting prospects for technical application. For example, because C60 readily accepts and donates electrons, it has possible application in batteries.

Uses of Fullerenes:

It is hoped fullerenes or their compounds may find uses as-

(a) Superconductors

(b) Semiconductors

(c) Lubricants

(d) Catalysts

(e) As highly tensile fibres for construction industry.

(f) Inhibiting agents in the activity of the AIDS virus.

VERSATILE NATURE OF CARBON:

The number of carbon compounds whose formulae are known to chemists was recently estimated to be about three million. This out numbers by a large margin the compounds formed by all the other elements put together. Why is it that this property is seen in carbon and no other elements?

It is due to its following unique properties:

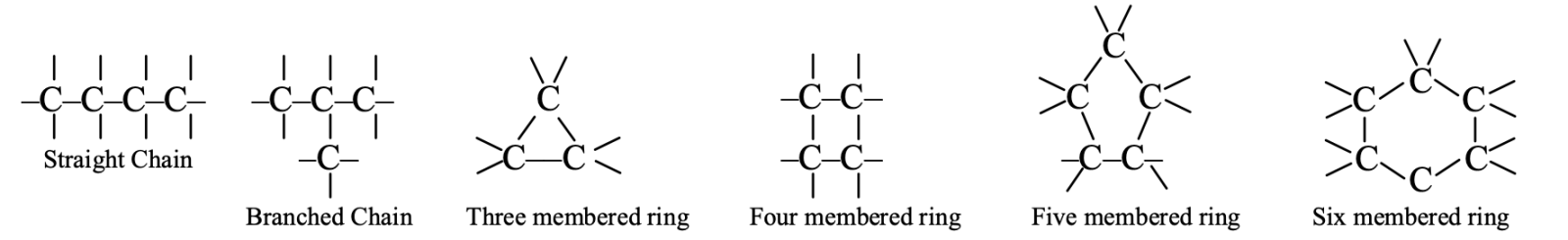

Catenation:

Carbon atoms have a unique ability to combine with one another to form chains. This property is called catenation. The valency of each carbon atom can be satisfied by combining with other carbon atoms. In this way, an indefinite number of carbon atoms can unite with one another to form molecules.

This property of catenation is due to

(a) Small size

(b) Unique electronic configuration

(c) Great strength of carbon-carbon bonds.

The chains formed by carbon-carbon bonding may be straight or branched of varying lengths or cyclic (ring) of different sizes.

Note: Both carbon and silicon have similar electronic configuration but carbon shows catenation to a much greater extent than silicon.

For example, carbon forms compounds with hydrogen in which hundreds of carbon atoms can be joined together. These compounds of carbon and hydrogen called hydrocarbons are very stable. On the other hand, silicon also forms compounds with hydrogen which contain chains only upto seven or eight silicon atoms. These compounds of silicon and hydrogen called silanes are, however, very reactive. This is mainly due to the reason that carbon-carbon bonds are much stronger than silicon-silicon bonds.

Tetracovalency of carbon:

Carbon has a valency of four. Therefore, it is capable of bonding with four other atoms of carbon or atoms of some other monovalent elements. Further, due to small size, the nucleus of carbon atom can hold its shared pairs of electrons strongly. As a result, the bonds that carbon forms with most of the other elements such as hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, sulphur, chlorine, etc. are very strong thereby making these compounds exceptionally stable. This further increases the number of carbon compounds.

Tendency to form multiple bonds:

Due to small size, carbon also forms multiple (double and triple) bonds with other carbon atoms, oxygen, and nitrogen. This multiplicity of carbon-carbon, carbon-oxygen and carbon-nitrogen bonds further increases the number of carbon compounds.

Isomerism:

Another reason for huge number of carbon compounds is the phenomenon of isomerism.

If a given molecular formula represents two or more structures having different properties, the phenomenon is called isomerism and the different structures are called isomers.

For example, the formula C4H10 represents two structures, the formula C5H12 represents three structures and the formula C6H14 represents five structures. The number of different structures with the same molecular formula further increases the number of carbon compounds.

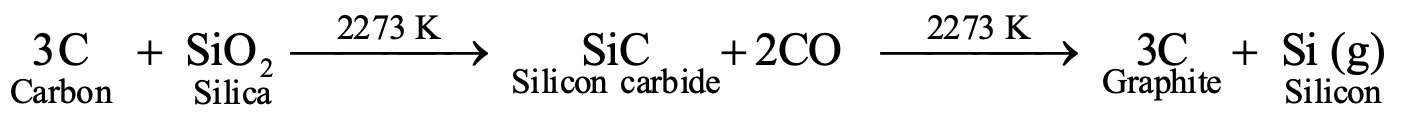

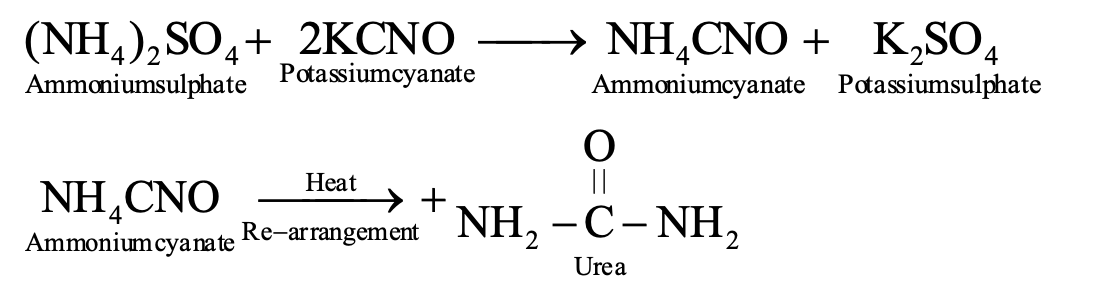

VITAL FORCE THEORY OR BERZELIUS HYPOTHESIS:

Organic compounds cannot be synthesized in the laboratory because they require the presence of a mysterious force (called vital force) which exists only in living organisms.

WOHLER’S SYNTHESIS:

In 1828, Friedrich Wohler synthesized urea (a well known organic compound) in the laboratory by heating ammonium cyanate. Urea is the first organic compound synthesized in the laboratory.

Orgnic Compounds

Since ancient times, minerals, plants and animals are the three major sources of naturally occurring substances. But it was only in the eighteenth century that these compounds were divided into two classes namely, Organic and Inorganic. Compounds like urea, sugar, oils, fats, dyes, proteins, vitamins, etc. which were isolated directly or indirectly from living organisms, such as animals and plants, were called Organic Compounds and the branch of chemistry which dealt with the study of these compounds was called Organic Chemistry.

Compounds like common salt, marble, alum, potassium nitrate, copper sulphate (blue vitriol), ferrous sulphate (green vitriol), zinc sulphate (white vitriol), etc., which were isolated from non-living sources, such as rocks and minerals, were called Inorganic Compounds and the branch of chemistry which dealt with the study of these compounds was called Inorganic Chemistry.

Note: Carbon compounds such as oxides of carbon (carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide), carbonates, bicarbonates, cyanides, etc. are not called organic compounds and hence are still studied under inorganic compounds. Organic Chemistry may be defined as the chemistry of hydrocarbons and their derivatives.

TYPES OF ORGANIC COMPOUNDS:

Some common types of organic compounds are:

- Hydrocarbons

- Haloalkanes

- Alcohols

- Aldehydes

- Ketones

- Carboxylic acids

- Esters

HYDROCARBONS

The organic compounds containing only carbon and hydrogen are called hydrocarbons. These are the simplest organic compounds and are regarded as parent organic compounds. All other compounds are considered to be derived from them by the replacement of one or more hydrogen atoms by other atoms or groups of atoms. The major source of hydrocarbons is petroleum.

TYPES OF HYDROCARBONS:

The hydrocarbons can be classified as:

Saturated Hydrocarbons:

(a) Alkanes: Alkanes are saturated hydrocarbons containing only carbon – carbon and carbon - hydrogen single covalent bonds.

General formula: CnH2n+2.

For eg.: CH4 (Methane)

C2H6 (Ethane)

Unsaturated Hydrocarbons:

(a) Alkenes: These are unsaturated hydrocarbons which contain carbon – carbon double bond. They contain two hydrogen atoms less than the corresponding alkanes.

General formula: CnH2n.

For eg.: C2H4 (Ethene)

C3H6 (Propene)

(b) Alkynes: They are also unsaturated hydrocarbons which contain carbon – carbon triple bond. They contain four hydrogen atoms less than the corresponding alkanes.

General formula: CnH2n–2.

For eg.: C2H2 (Ethyne)

C3H4 (Propyne)

STRUCTURE OF SATURATED AND UNSATURATED HYDROCARBONS

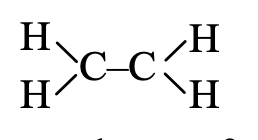

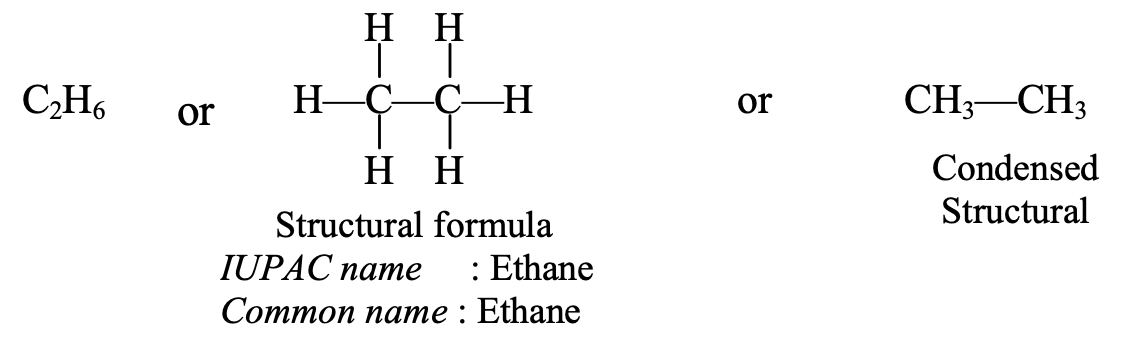

(a) Structure of ethane (C2H6). To derive the structure of ethane, the following steps are followed.

Step 1. Link the two carbon atoms through a single bond, we have

C - C

Step 2. Satisfy the tetracovalency of each carbon by connecting the required number of hydrogen atoms to each carbon. Since in ethane, one valency of each carbon is satisfied by connecting the two carbon atoms together, therefore, attach three hydrogen atoms to each carbon, to satisfy the tetracovalency of carbon. Thus, the structure of ethane is

Such structures in which the bonds between different atoms are shown by dashes are called complete structural formulae or graphic formulae or displayed formulae. These structural formulae can be further abbreviated by omitting some or all the covalent bonds. For example, ethane may be written as CH3––CH3 or CH3CH3. These are called condensed structural formulae. The electron dot structure of ethane is shown in figure.

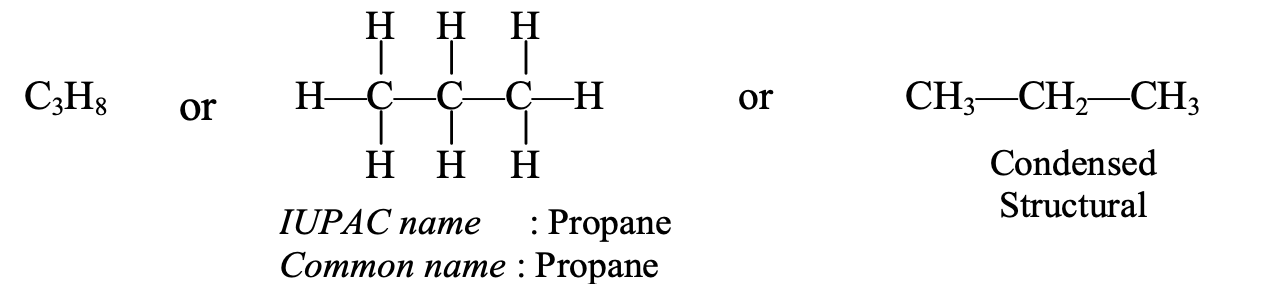

In a similar way, we can derive the structure of propane with the molecular formula, C3H8, C4H10 (Butane), C5H12 (Pentane) and so on.

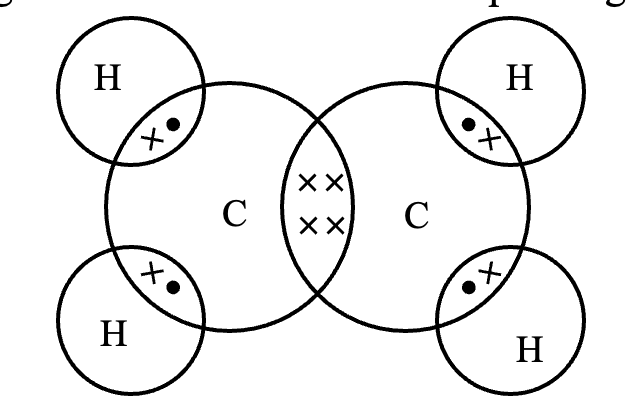

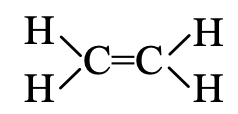

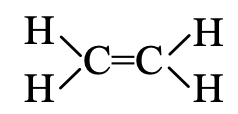

(b) Structure of ethene (C2H4). Another compound of carbon has the molecular formula, C2H4. It is called ethene (ethylene). Its structure can be derived by following the steps :

Step 1. Link the two carbon atoms together by a single bond, we have,

C - C

Step 2. Since there are a total of four hydrogen atoms, attach two hydrogen atoms to each carbon, we have,

Step 3. In the above formula, one valency of each carbon is free or unsatisfied. This can be satisfied if there is a double bond between the two carbon atoms. Thus, the graphic formula of ethene is

The electron dot structure of ethene is given in figure.

In ethene, the carbon atoms are held together by two pairs of electrons, therefore, a carbon-carbon double bond is shorter (134 pm) and stronger (599 kJ mol–1) than a carbon-carbon single bond in ethane (bond length = 154 pm and bond strength = 348 kJ mol–1).

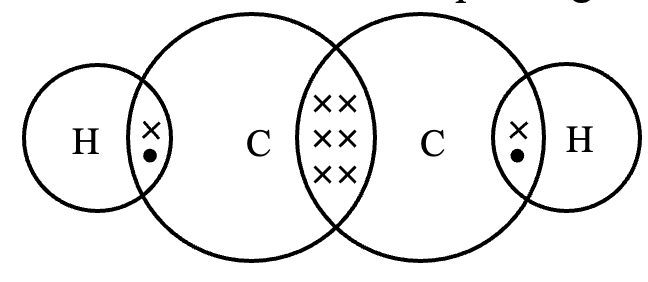

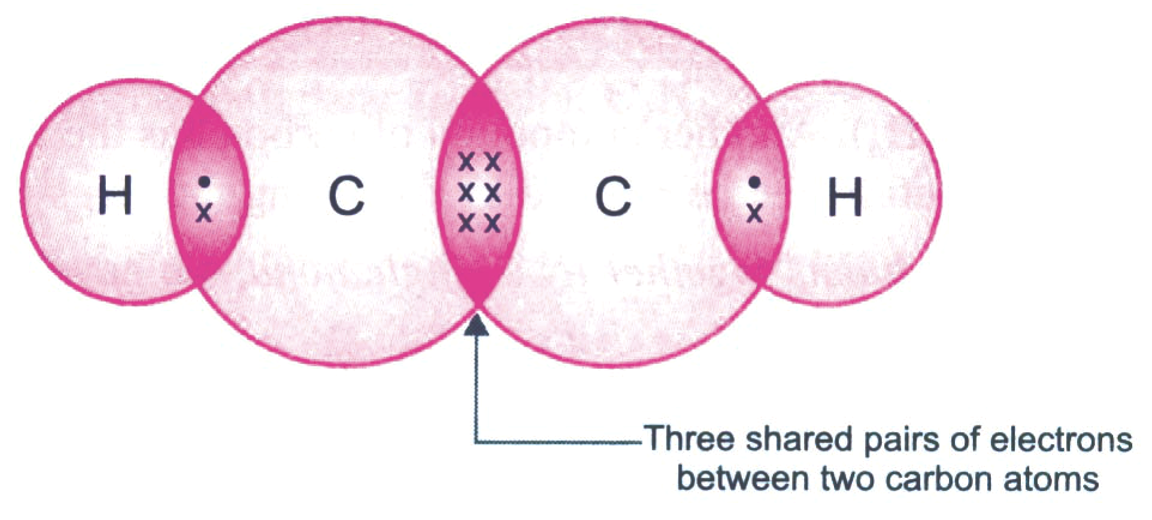

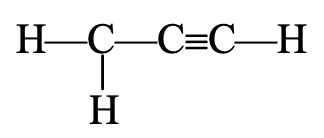

(c) Structure of ethyne (C2H2). There is yet another compound of carbon and hydrogen having the molecular formula, C2H2. It is called ethyne (acetylene). Its structure can be derived following the steps :

Step 1. Link the two carbon atoms by a single bond, we have,

C – C

Step 2. Since there are only two hydrogen atom, each attach to each carbon, we have,

H – C – C – H

Step 3. Now, two of the four valencies of each carbon are satisfied. In order to satisfy the remaining two valencies of each carbon, connect the two carbon atoms by a triple bond. Thus, the graphic formula of ethyne is

H – C ≡ C – H

The electron dot structure of ethyne is shown in figure below:

In ethyne, the carbon atoms are held together by three pairs of electrons, therefore a carbon-carbon triple bond is even shorter (120 pm) and stronger (823 kJ mol–1) than a carbon-carbon double bond.

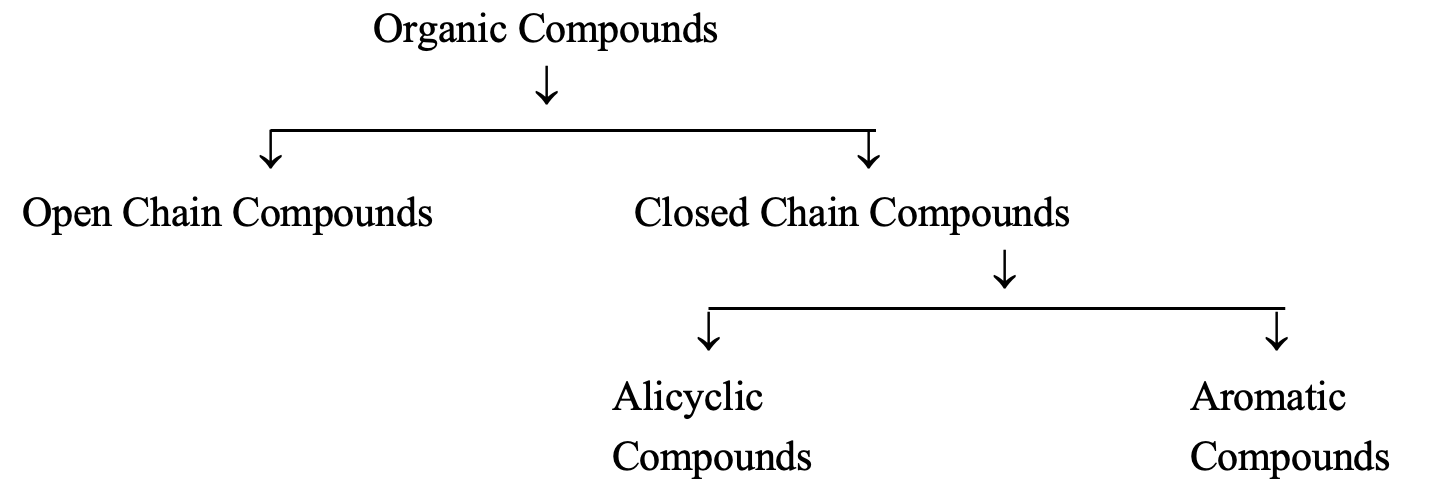

CLASSIFICATION OF ORGANIC COMPOUNDS:

The organic compounds are very large in number on account of the self -linking property of carbon called catenation. These compounds have been further classified as open chain and cyclic compounds.

OPEN CHAIN COMPOUNDS:

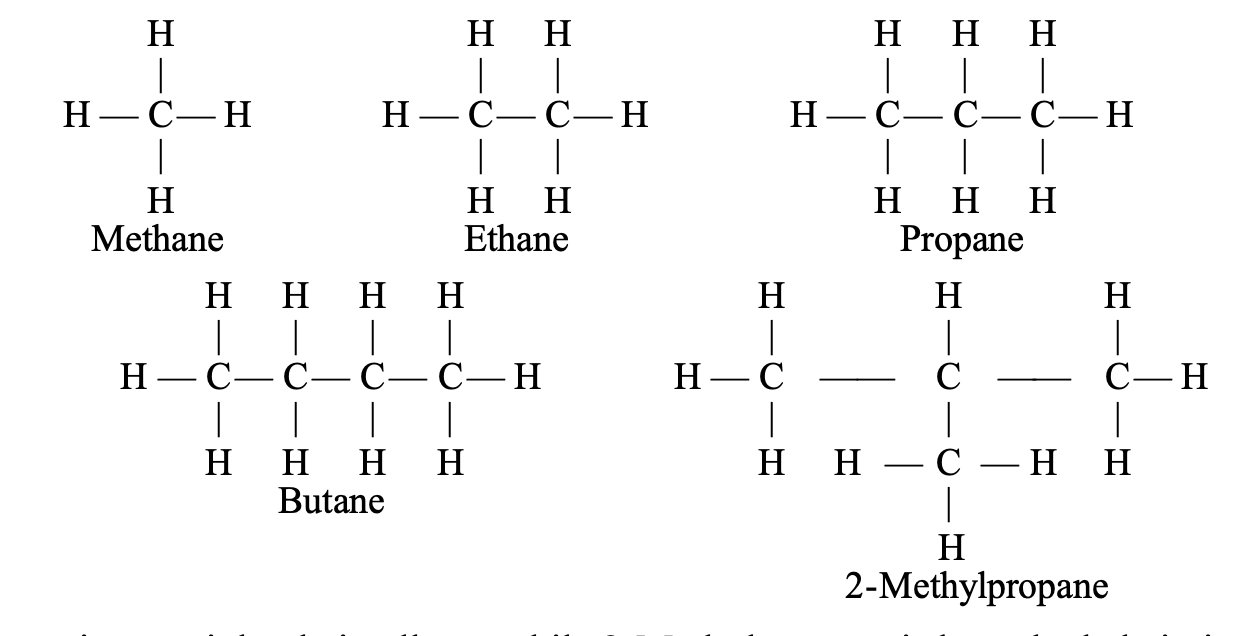

These compounds contain an open chain of carbon atoms which may be either straight chain or branched chain in nature. Apart from that, they may also be saturated or unsaturated based upon the nature of bonding in the carbon atoms. For example:

Butane is a straight chain alkane while 2-Methylpropane is branched chain in nature.

CLOSED CHAIN COMPOUNDS:

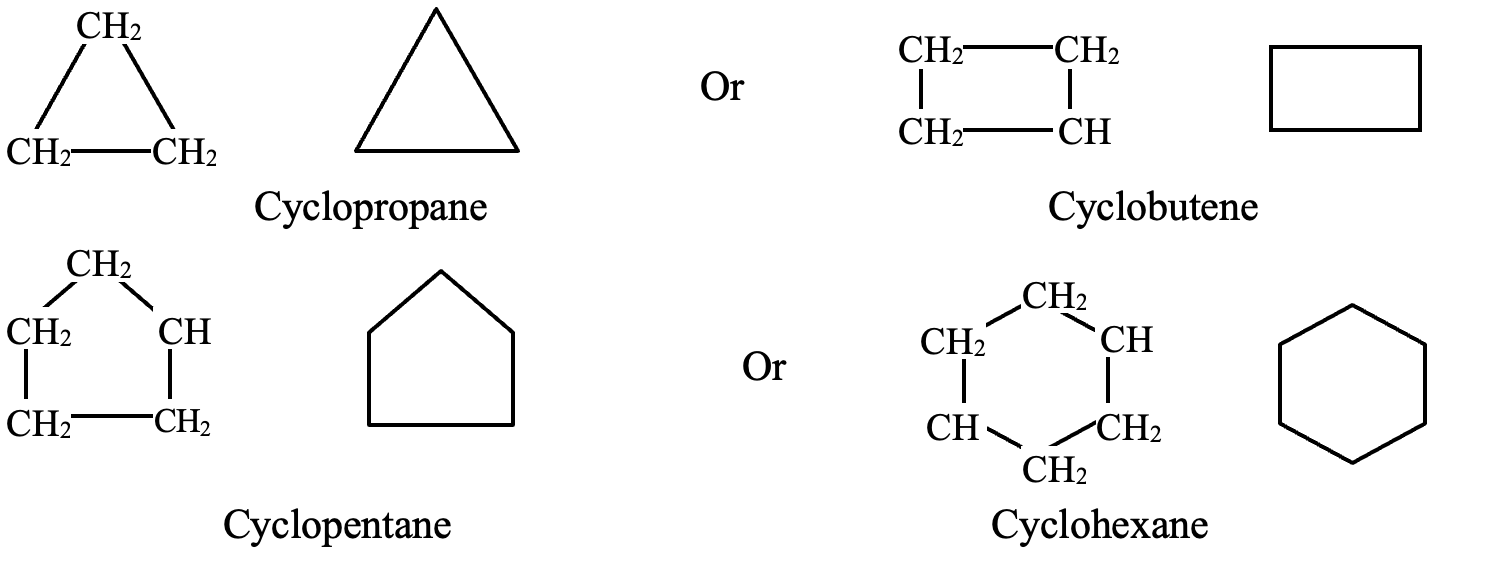

Apart from the open chains, the organic compounds can have cyclic or ring structures. A minimum of three atoms are needed to form a ring. These compounds have been further classified into following types.

Alicyclic Compounds:

Those carbocyclic compounds which resemble aliphatic compounds in their properties are called alicyclic compounds.

For e.g.,

Cyclopentane Cyclohexane

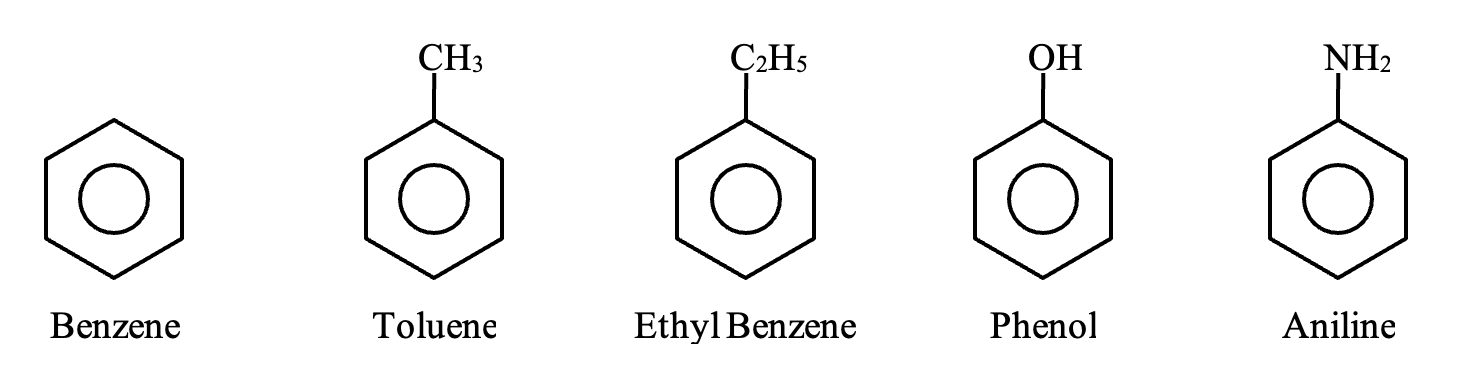

Aromatic Compounds:

Organic compounds which contain one or more fused or isolated benzene rings are called aromatic compounds.

NOMENCLATURE OF ORGANIC COMPOUNDS:

Nomenclature means the assignment of names to organic compounds. There are two main systems of nomenclature of organic compounds –

- Trivial system

- IUPAC system (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry)

Basic Rules of Nomenclature or Compounds in IUPAC System:

For naming simple aliphatic compounds, the normal saturated hydrocarbons have been considered as the parent compounds and the other compounds as their derivatives obtained by the replacement of one or more hydrogen atoms with various functional groups.

Each systematic name has first two or all three of the following parts:

(i) Word Root:

The basic unit is a series of word root which indicate linear or continuous number of carbon atoms.

(ii) Primary Suffix:

Primary suffixes are added to the word root to show saturation or unsaturation in a carbon chain.

(iii) Secondary Suffix:

Suffixes added after the primary suffix to indicate the presence of a particular functional group in the carbon chain are known as secondary suffixes.

Naming straight-chain saturated hydrocarbons:

- A compound is named after the longest straight carbon chain in the molecule of the compound.

- The prefix of a name indicates the number of carbon atoms present in the chain.

According to the number of carbon-atoms in a hydrocarbon the naming is done as:

| Number of carbon atoms | Names as Prefix | Number of carbon atoms | Names as Prefix |

| 1 | meth- | 6 | hex- |

| 2 | eth- | 7 | hept- |

| 3 | prop- | 8 | oct- |

| 4 | but- | 9 | non- |

| 5 | pent- | 10 | dec- |

- For saturated hydrocarbons, the suffix-ane is added to these prefixes as shown below:

| Hydrocarbon | Number of carbon atoms | Prefix | Suffix | Name |

| CH4 | 1 | meth- | -ane | methane |

| C2H6 | 2 | eth- | -ane | ethane |

| C3H8 | 3 | prop- | -ane | propane |

| C4H10 | 4 | but- | -ane | butane |

| C5H12 | 5 | pent- | -ane | pentane |

| C6H14 | 6 | hex- | -ane | hexane |

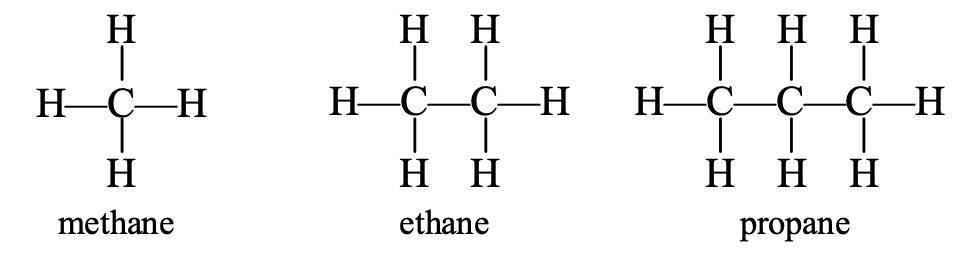

For example,

- Naming of CH4: The structure of CH4 is

This compound contains 1 carbon atom which is indicated by writing ‘meth’. This compound has all single bonds, so it is saturated. The saturated hydrocarbon is indicated by the ending ‘ane’. On joining ‘meth’ and ‘ane’, the IUPAC name of this compound becomes ‘methane’ (meth + ane = methane).

- Naming of C2H6 : The structural formula of C2H6 is given below :

This hydrocarbon contains 2 carbon atoms which are indicated by writing ‘eth’. This hydrocarbon has all single bonds, so it is saturated. The saturated hydrocarbon is indicated by using the suffix or ending ‘ane’. Now, by joining ‘eth’ and ‘ane’, the IUPAC name of the above hydrocarbon becomes ‘ethane’ (eth + ane = ethane).

- Naming of C3H8 : The structural formula of the C3H8 hydrocarbon is given below :

This hydrocarbon contains 3 carbon atoms which are indicated by the word ‘prop’. This hydrocarbon has all single bonds, so it is saturated. The saturated hydrocarbon is indicated by using the ending ‘ane’. On joining ‘prop’ and ‘ane’, the IUPAC name of the above hydrocarbon becomes ‘propane’ (prop + ane = propane).

- Naming of C4H10: One of the structural formula of C4H10 hydrocarbon is given below :

This hydrocarbon has 4 carbon atoms in one continuous chain which are represented by the word ‘but’. This hydrocarbon has all single bonds, so it is saturated. A saturated hydrocarbon is represented by using the ending ‘ane’. So, joining ‘but’ and ‘ane’, IUPAC name of the above given hydrocarbon structure becomes ‘butane’ (but + ane = butane).

Note The above structure has 4 carbon atoms in one continuous chain. Such straight chain compounds are termed ‘normal’ in the common names. So, the common name of the hydrocarbon having the above structure is ‘normal-butane’ which is written in short as ‘n-butane’ (n for normal). Thus, the IUPAC name of the above hydrocarbon is butane but its common name is n-butane.

Naming of C5H12: This hydrocarbon can have three possible structures. The simplest one is given below:

-

This hydrocarbon has 5 carbon atoms in one continuous chain which are indicated by the word ‘pent’. This hydrocarbon has all single bonds, so it is saturated. A saturated hydrocarbon is indicated by using the ending ‘ane’. Now, by joining pent and ane, the IUPAC name of the above given hydrocarbon structure becomes pentane (pent + ane = pentane). The common name of this hydrocarbon is normal-pentane (which is written in short as n-pentane). Thus, the IUPAC name of the above hydrocarbon is pentane but its common name is n-pentane.

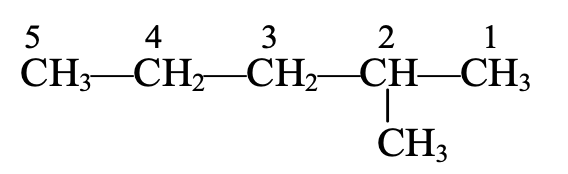

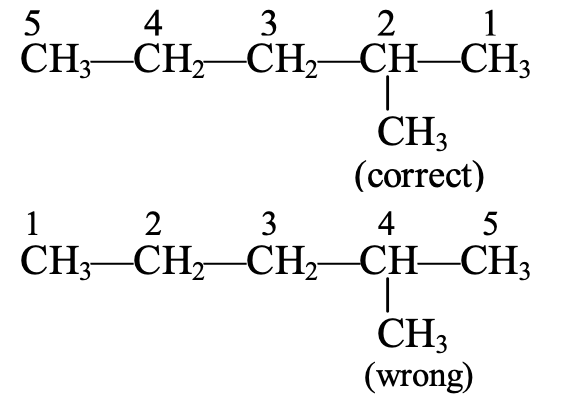

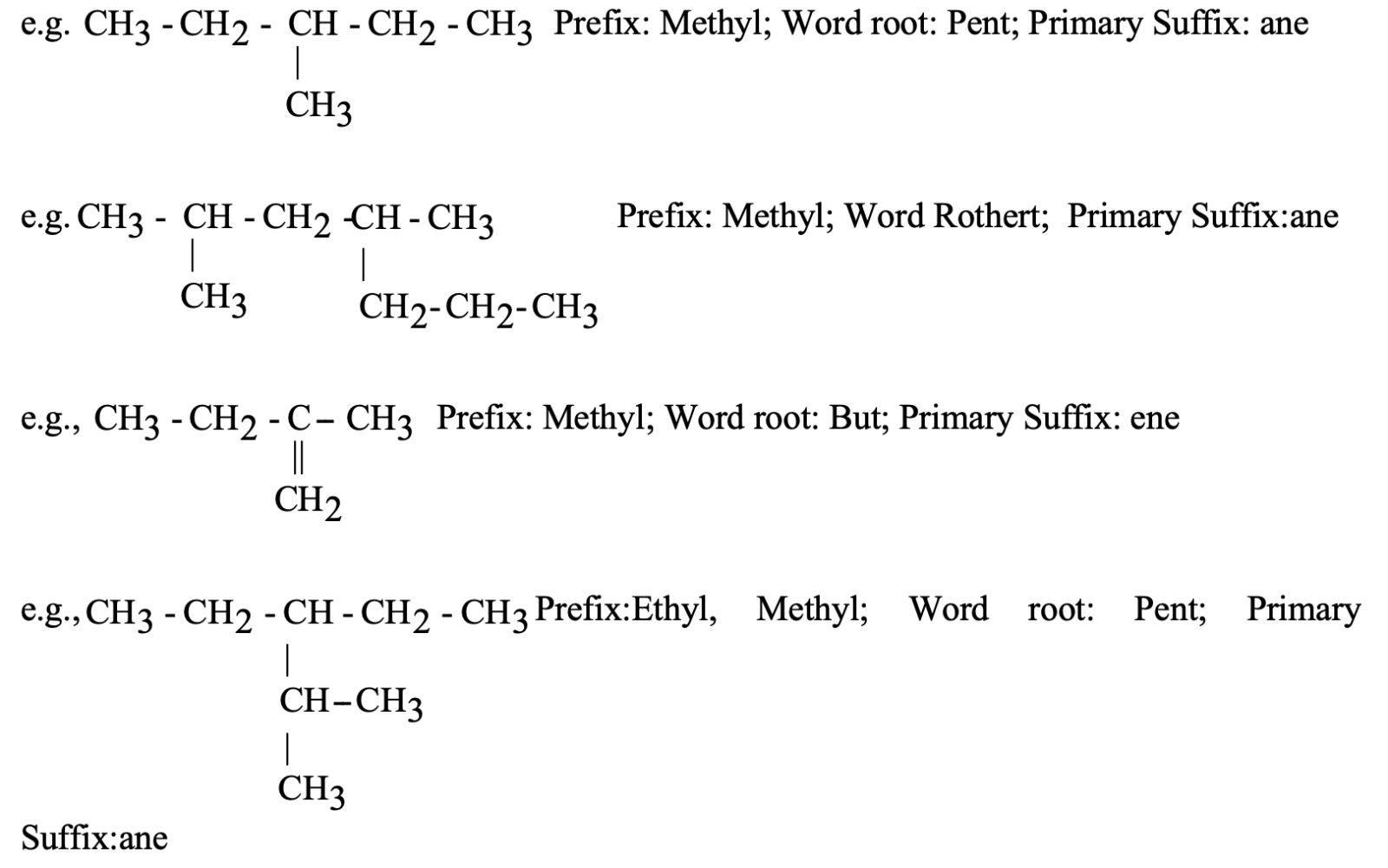

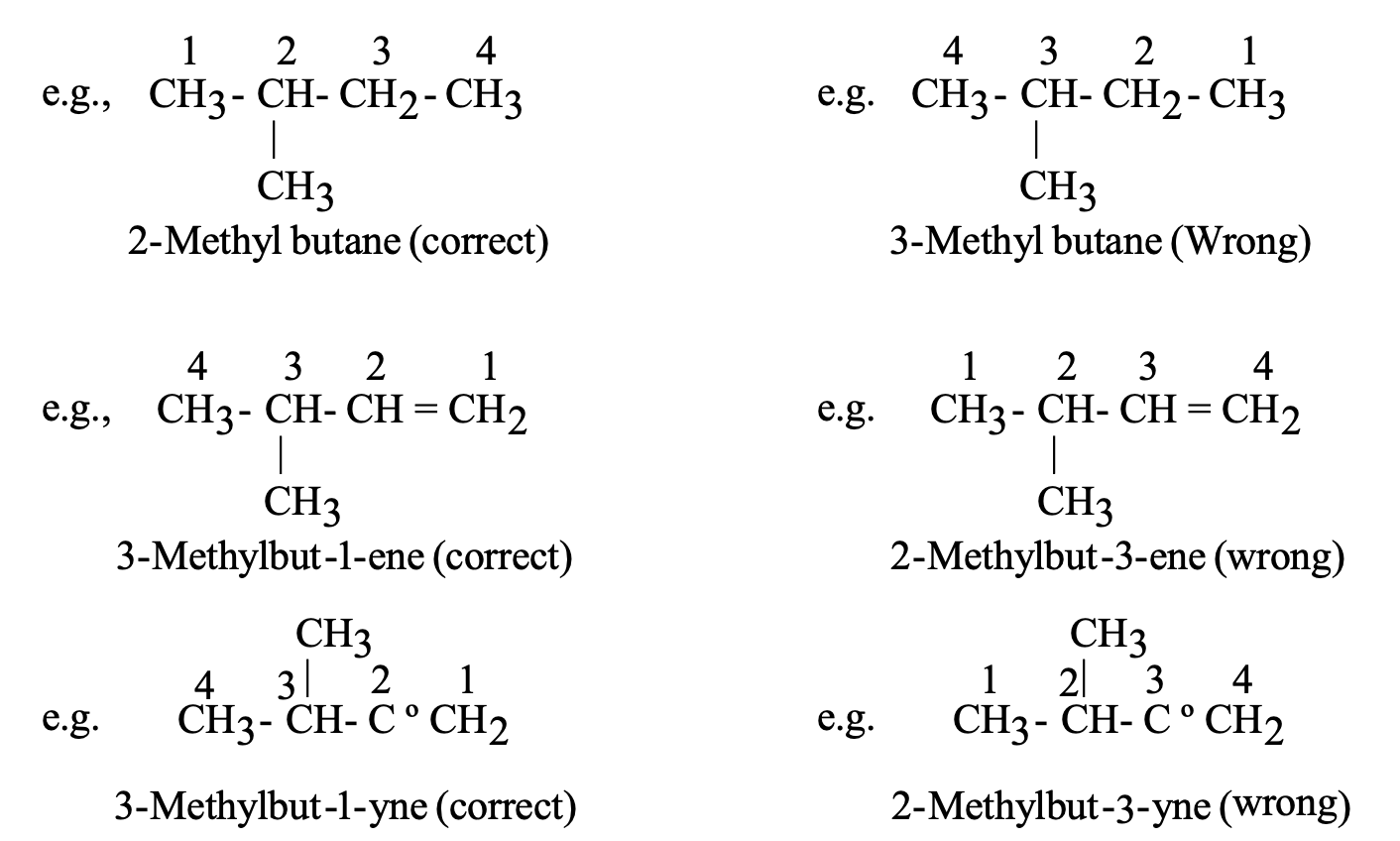

Naming branched-chain, saturated hydrocarbons:

In order to name the saturated hydrocarbons having branched chains by the IUPAC method, we should remember the following rules :

- The longest chain of carbon atoms in the structure of the compound (to be named) is selected first. The compound is then named as a derivative of the alkane hydrocarbon which corresponds to the longest chain of carbon atoms (This is called parent hydrocarbon).

- The alkyl groups present as side chains (branches) are considered as functional groups and named separately as methyl (CH3—) or ethyl (C2H5—) groups.

- The carbon atoms of the longest carbon chain are numbered in such a way that the alkyl groups (substituents) get the lowest possible number (smallest possible number).

- The position of alkyl group is indicated by writing the number of carbon atom to which it is attached.

- Thus, IUPAC name is given as

Position and name of alkyl group + parent hydrocarbon

- If two or three same alkyl derivatives are present on same carbon atom, then prefix ‘di’ or ‘tri’ can be used respectively.

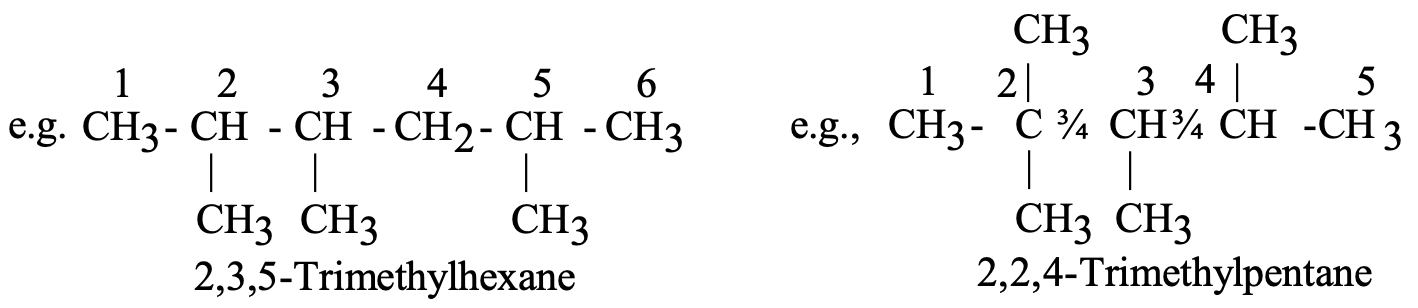

Lets understand with the help of few examples:

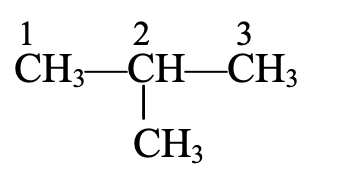

Ex.

The longest chain contains three C-atoms. The saturated hydrocarbon containing three carbon atoms is propane.

The methyl group (CH3- is attached to C-atom number 2 (numbering from either side gives number 2 to the C-atom to which the methyl group is attached).

Thus, the name of the compound is 2-methyl propane.

Ex.

The longest chain contains five C-atoms. The saturated hydrocarbon containing five C-atoms is pentane.

The numbering of C-atoms in the longest chain is done from the C-atom that is nearest to the methyl group which is present as the branched chain. Thus,

Hence, the correct name will be 2-methyl pentane (and not 4-methylpentane).

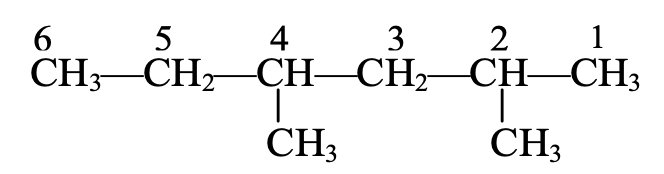

Ex.

The longest chain contains six C-atoms. The saturated hydrocarbon containing six C-atoms is hexane.

The methyl groups are attached to C-atom numbers 2 and 4. Hence, the name of this compound will be 2, 4-dimethyl hexane.

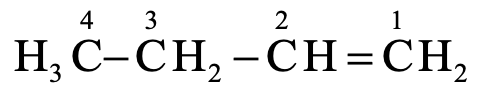

Naming unsaturated hydrocarbons containing a double bond:

- An unsaturated hydrocarbon containing a double bond between two adjacent carbon atoms is named by taking the prefix of the name of the corresponding saturated hydrocarbon and by replacing the suffix –ane by –ene.

- The position of the double bond is indicated by a numerical prefix. This numerical prefix indicates the number of the carbon atom preceding the double bond.

Lets understand with the help of examples :

- Naming of C2H4 : The saturated hydrocarbon corresponding to two carbon atoms is ethane. C2H4 contains a double bond. Hence, the IUPAC name of this hydrocarbon will be ethene.

- Naming of C4H8: This unsaturated hydrocarbon is structurally represented as :

It has four carbon atoms in its molecule. The saturated hydrocarbon corresponding to four carbon atoms in butane. Since the molecule has a double bond, the IUPAC name of the compound is butene. As the double bond is preceded by carbon atom numbered 1, the IUPAC name of the compound will be 1-butene.

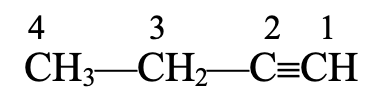

Naming unsaturated hydrocarbons containing a triple bond:

An unsaturated hydrocarbon containing a triple bond between two adjacent carbon atoms is named by taking the prefix of the name of the corresponding saturated hydrocarbon and by replacing the suffix-ane by the suffix –yne.

For example,

- Naming of C2H2 The structure of this hydrocarbon is

H–C C–H

It contains two carbon atoms. The saturated hydrocarbon corresponding to two carbon atoms is ethane.

As it contains a triple bond, the suffix-ane of ethane is replaced by –yne.

Thus, the IUPAC name is ethyne.

- Naming of C3H4 The structure of this hydrocarbon is

This hydrocarbon contains three carbon atoms. The saturated hydrocarbon corresponding to three carbon atoms is propane. As it contains a triple bond, the suffix –ane of propane is replaced by –yne. Hence, the IUPAC name is propyne.

- Naming of C4H6 The structural representation of this unsaturated hydrocarbon is,

There are four carbon atoms in the molecule. The saturated hydrocarbon with the same number of carbon atoms is butane. There is a triple bond, so the IUPAC name of this hydrocarbon will be 1-butyne.

A BRANCHED CHAIN HYDROCARBON IS NAMED USING THE FOLLOWING GENERAL IUPAC RULES:

Rule-I: Longest chain rule:

Select the longest possible continuous chain of carbon atoms. If some multiple bond is present, the chain selected must contain the multiple bond.

(i) The number of carbon atoms in the selected chain determines the word root.

(ii) Saturation or unsaturation determines the primary suffix (P. suffix).

(iii) Alkyl substituents are indicated by prefixes.

Rule-II: Lowest Number rule:

The chain selected is numbered in terms of Arabic numerals and the position of the alkyl groups are indicated by the number of the carbon atom to which alkyl group is attached.

(i) The numbering is done in such a way that the substituent carbon atom has the lowest possible number.

The name of the compound, in general, is written in the following sequence.

(Position of substituents) – (prefixes) (word root) (p – suffix)

Rule-III: Use of prefixes di, tri etc.:

If the compound contains more than one similar alkyl groups, their positions are indicated separately and an appropriate numerical prefix, di, tri, etc., is attached to the name of the substituents. The positions of the substituents are separated by commas.

Rule-IV: Alphabetical arrangement of prefixes:

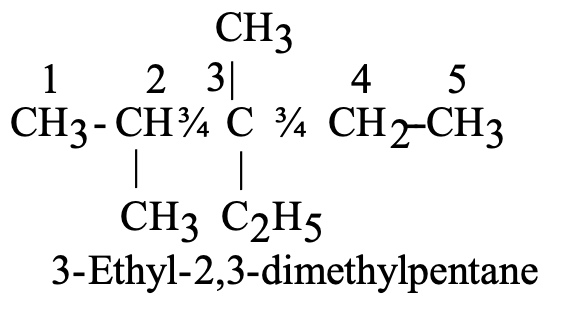

If there are different alkyl substituents present in the compound their names are written in the alphabetical order. However, the numerical prefixes such as di, tri etc. are not considered for the alphabetical order. For eg.:

Rule-V: Naming of different alkyl substituents at the equivalent positions:

If two alkyl substituents are present at the equivalent position then numbering of the chain is done in such a way that the alkyl group which comes first in alphabetical order gets the lower position.

Isomers

Let us consider the structural formulae of the first three members of the alkane series, i.e., the structural formulae of methane, ethane and propane.

If the positions of carbon and hydrogen atoms in these molecules are rearranged, the same structural formulae are obtained. This means that the structural formulae of the first three members of the alkane series remain unchanged, even if the carbon and hydrogen atoms in them are rearranged.

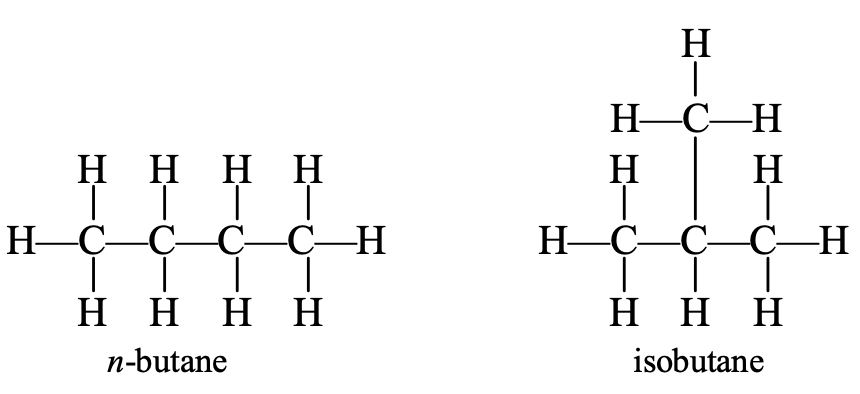

Now consider the fourth member of the alkane series, i.e., butane. In butane, carbon and hydrogen atoms may be arranged differently to give different structures and, hence, different compounds.

Both n-butane and isobutane have the same molecular formula (C4H10) but their structures are different. In n-butane, the carbon atoms form a longer straight chain, while in isobutene, there is a shorter straight chain and a branch. In the straight chain (n-butane), no carbon atom is bonded to more than two carbon atoms, but in the branched chain (isobutene), one carbon atom is bonded to three other carbon atoms n-butane and isobutene are called isomers.

CHARACTERISTICS OF ISOMERS:

- All the isomers of a compound have the same molecular formula.

- The isomers of a compound have different structures.

- The physical and chemical properties of all the isomers of a compound differ from one another.

Note: The different structures of isomers arise due to different arrangements of carbon atoms in their molecules. Due to the different structures of isomers their properties are different.

For example,

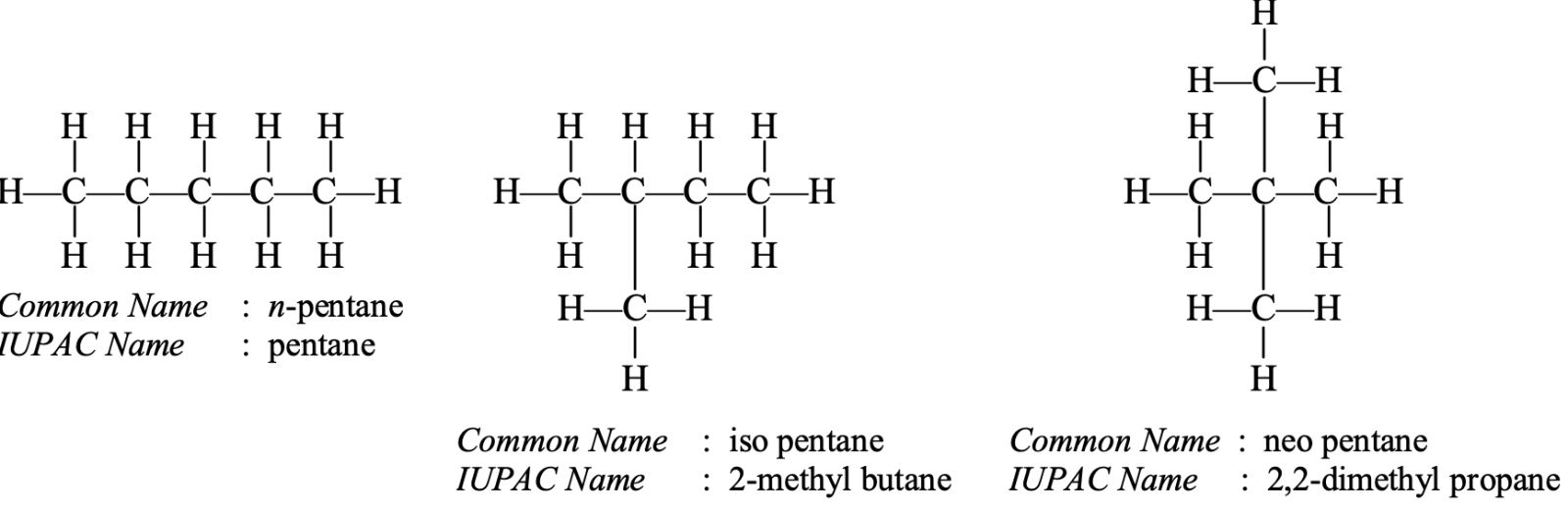

- Isomers of pentane: The molecular formula of pentane is C5H12. Three isomers corresponding to this formula are possible.

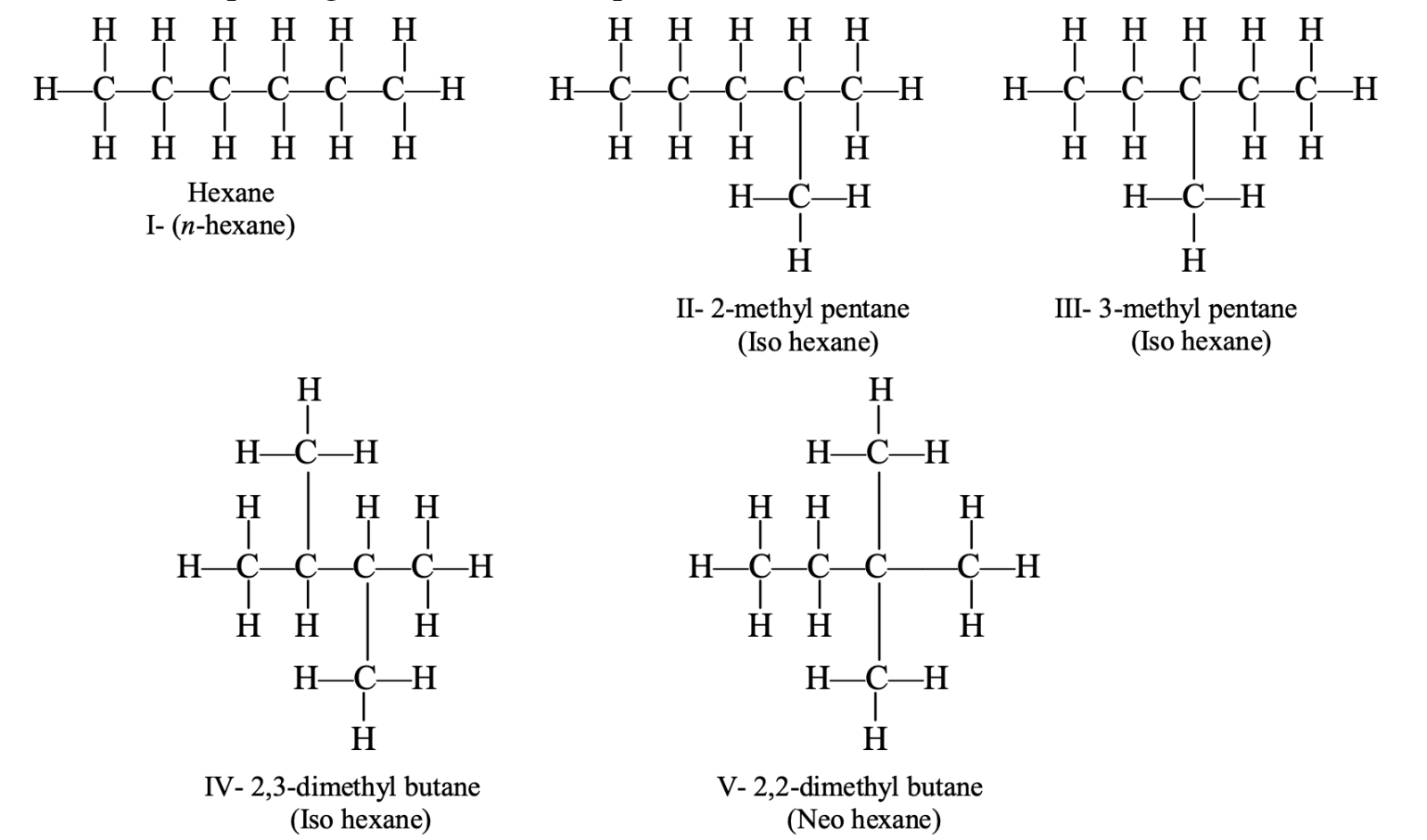

- Isomers of hexane: The molecular formula of hexane is C6H14. Five isomers corresponding to this formula are possible.

HOMOLOGOUS SERIES:

All the organic compounds having similar structures show similar properties and they are put together in the same group or series. In doing so, the organic compounds are arranged in the order of increasing molecular masses.

A homologous series is a group of organic compounds having same general formula, similar structures and similar chemical properties in which the successive compounds differ by CH2 group. The various organic compounds of a homologous series are called homologues.

For example:

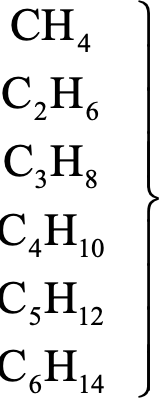

The homologues of alkanes are represented by the general formula CnH2n+2. The homologues of alkanes are shown in table.

Homologues of alkanes:

|

Compound |

Molecular formula |

Difference |

|

Methane Ethane Propane Butane Pentane Hexane |

|

—CH2 |

The homologous series of alkenes and alkynes are shown in tables below:

Homologues of alkenes:

Homologues of alkenes:

Characteristics of a Homologous Series

- All the members of a homologous series can be represented by the same general formula. For example, all the members of the alkane series can be represented by the general formula CnH2n+2.

- Any two adjacent homologues differ by 1 carbon atom and 2 hydrogen atoms in their molecular formulae. That is, any two adjacent homologues differ by a CH2 group. For example, the first two adjacent homologues of the alkane series, methane (CH4) and ethane (C2H6) differ by 1 carbon atom and 2 hydrogen atoms. The difference between CH4 and C2H6 is CH2.

- The difference in the molecular masses of any two adjacent homologues is 14 u. For example, the molecular mass of methane (CH4) is 16 u, and that of its next higher homologue ethane (C2H6) is 30 u. So, the difference in the molecular masses of ethane and methane is 30 – 16 = 14 u.

- All the compounds of a homologous series show similar chemical properties. For example, all the compounds of alkane series like methane, ethane, propane, etc., undergo substitution reactions with chlorine.

- The members of a homologous series show a gradual change in their physical properties with increase in molecular mass. For example, in the alkane series as the number of carbon atoms per molecule increases, the melting points, boiling points and densities of its members increase gradually as shown in the table below:

| Alkanes | Formula | m.p. (°C) | b.p. (°C) | Density g.cm–3(20°C) |

| Methane | CH4 | –183 | –164 | Gas |

| Ethane | C2H6 | –172 | –89 | Gas |

| Propane | C3H8 | –188 | –45 | Gas |

| Butane | C4H10 | –135 | –0.6 | Gas |

| Pentane | C5H12 | –130 | 36 | 0.625 |

| Hexane | C6H14 | –95 | 69 | 0.659 |

COMPOUNDS CONTAINING C, H AND O

We have studied earlier about the compounds containing C and H only are called hydrocarbons. Now, we will study about the compounds where carbon forms bonds with other elements such as halogens, oxygen, nitrogen, sulphur and phosphorus.

Organic molecules except hydrocarbons can be broadly divided into two parts :

FUNCTIONAL GROUP:

An atom or a group of atoms in an organic molecule that is responsible for the compound’s characteristic reactions and determines its properties is known as a functional group.

(i) The functional group in an organic molecule is the most reactive part of the molecule.

(ii) The chemical properties of an organic compound are determined by the functional group of its molecule while the physical properties of the compounds are determined by the remaining part of the molecule.

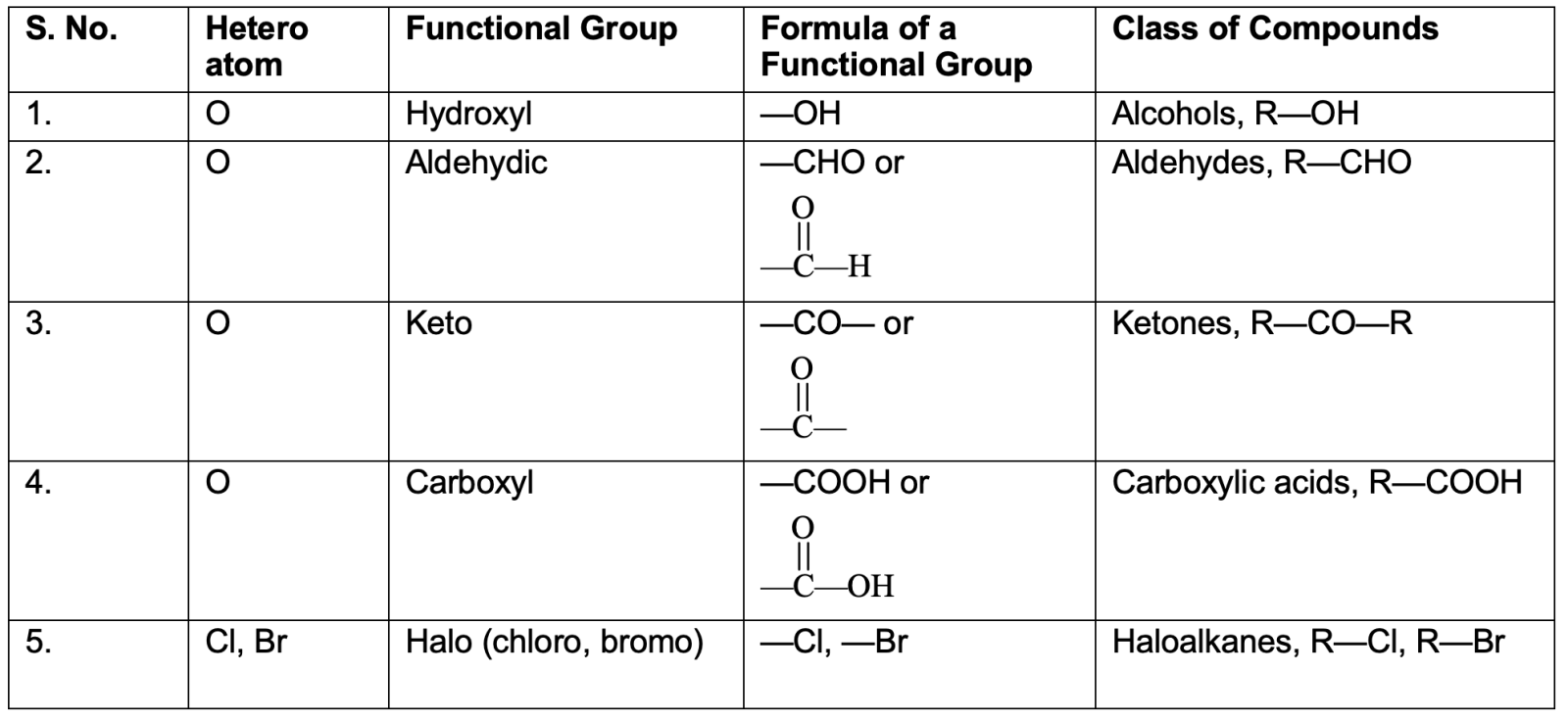

Some of the important functional groups and their corresponding compounds are discussed below:

- Halo Group : –X (X can be Cl, Br or I)

The halo group can be chloro, —Cl; bromo, —Br ; or iodo, —I, depending upon whether a chlorine, bromine or iodine atom is linked to a carbon atom of the organic compound.

The elements chlorine, bromine and iodine are collectively known as halogens, so the chloro group, bromo group and iodo group are called halo groups and represented by the general symbol —X. The halo group is present in chloromethane (CH3—Cl), bromomethane (CH3—Br) and iodomethane (CH3—I). Halo group is also known as halogen group. The haloalkanes can be written as R—X (where R is an alkyl group and X is the halogen atom).

- Alcohol Group: —OH

The alcohol group is made up of one oxygen atom and one hydrogen atom joined together. The alcohol group is also known as alcoholic group or hydroxyl group. The compounds containing alcohol group are known as alcohols. The examples of compounds containing alcohol group are : methanol, CH3OH, and ethanol, C2H5OH. The general formula of an alcohol can be written as R—OH (where R is an alkyl group like CH3, C2H5, etc., and OH is the alcohol group).

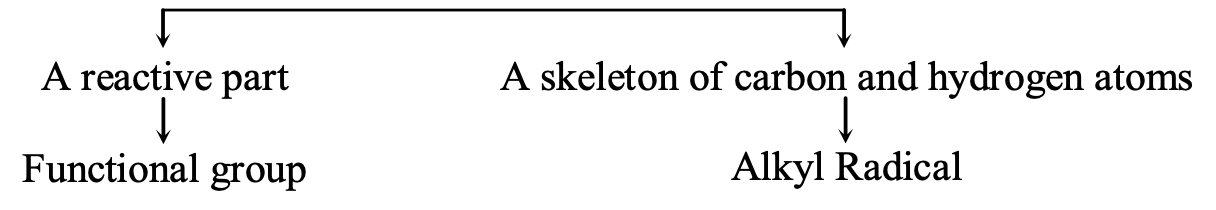

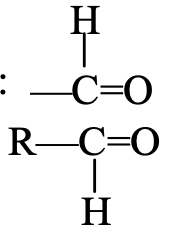

- Aldehyde Group : -CHO or

The aldehyde group consists of one carbon atom, one hydrogen atom and one oxygen atom joined together. The oxygen atom of the aldehyde group is attached to the carbon atom. The carbon atom of the aldehyde group is attached to either a hydrogen atom or an alkyl group. The aldehyde group is sometimes called aldehydic group. The compounds containing aldehyde group are known as aldehydes. The examples of compounds containing an aldehyde group are : methanal, HCHO, and ethanal, CH3CHO. The aldehydes can be represented by the general formula R—CHO (where R is an alkyl group).

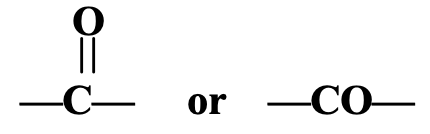

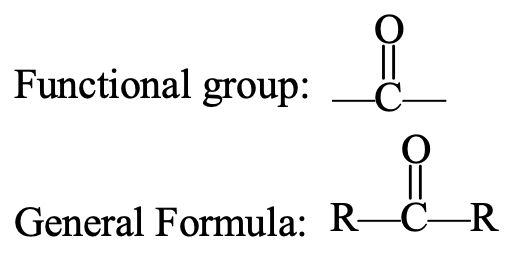

- Ketone Group: C = O or

The ketone group consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom. The oxygen atom of the ketone group is joined to the carbon atom by a double bond. The carbon atom of the ketone group is attached to two alkyl groups (which may be same or different). The ketone group is sometimes called a ketonic group. The compounds containing ketone group are known as ketones. The examples of compounds containing ketone group are : propanone, CH3COCH3, and butanone, CH3COCH2CH3.

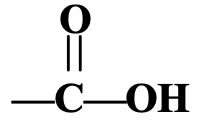

- Carboxylic Acid Group: - COOH or

Carboxylic acid group is present in methanoic acid, H—COOH and ethanoic acid, CH3—COOH. The carboxylic acid group is also called just carboxylic group or carboxyl group. The organic compounds containing carboxylic acid group (—COOH group) are called carboxylic acids or organic acids.

The functional groups are summarized in the table below:

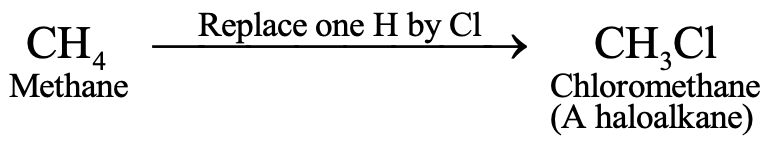

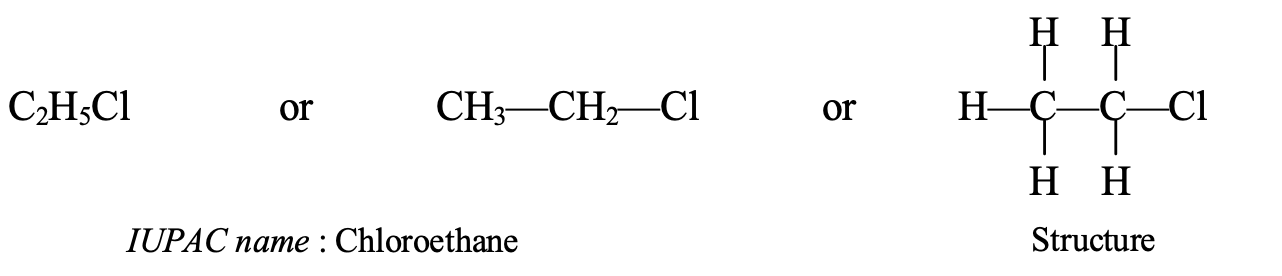

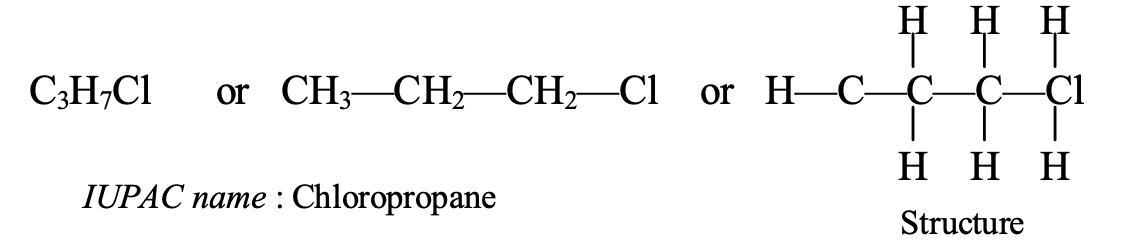

HALOALKANES

When one hydrogen atom of an alkane is replaced by a halogen atom, we get haloalkane (also called halogenoalkane). For example, when one hydrogen atom of methane is replaced by a chlorine atom, we get chloromethane :

Chloromethane is a haloalkane. The general formula of haloalkanes is CnH2n+1X (where X represents Cl, Br or I).

Naming of Haloalkanes:

There are two methods :

- The common method: In this method the name of the parent alkyl group is combined with the word halide. For example, the common name of CH3Cl is methyl chloride.

- The IUPAC System: According to this system, haloalkanes are named after the parent alkane by using a prefix to show the presence of the halo group such as chloro (–Cl), bromo (–Br) or iodo (–I) group.

For example,

- Naming of CH3Cl: This compound contains 1 carbon atom so its parent alkane is methane, CH4. This compound contains a chloro group (—Cl group) which is to be indicated by the prefix ‘chloro’. So, by combining chloro and methane we get the name chloromethane.

The common name of chloromethane (CH3Cl) is methyl chloride. Please note that CH3Br will be bromomethane (or methyl bromide).

- Naming of C2H5Cl: This compound contains 2 carbon atoms so its parent alkane is ethane. It also contains a chloro group. So, the IUPAC name of C2H5Cl becomes chloroethane.

- Naming of C3H7Cl: This compound contains 3 carbon atoms so its parent alkane is propane. It also has a chloro group. So, the IUPAC name of C3H7Cl becomes chloropropane.

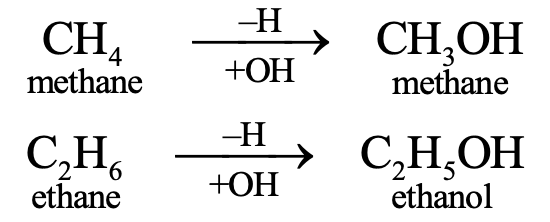

Alcohols

Alcohols are a class of compounds which contain carbon, hydrogen and oxygen. Alcohol is obtained by the replacement of one hydrogen atom in an alkane by a hydroxyl group. For example, replacement of one hydrogen atom in methane by a hydroxyl group produces a new compound called methanol. Similarly, if one hydrogen atom in ethane is replaced by a hydroxyl group, we get ethanol.

Functional group : —OH

General formula : R—OH

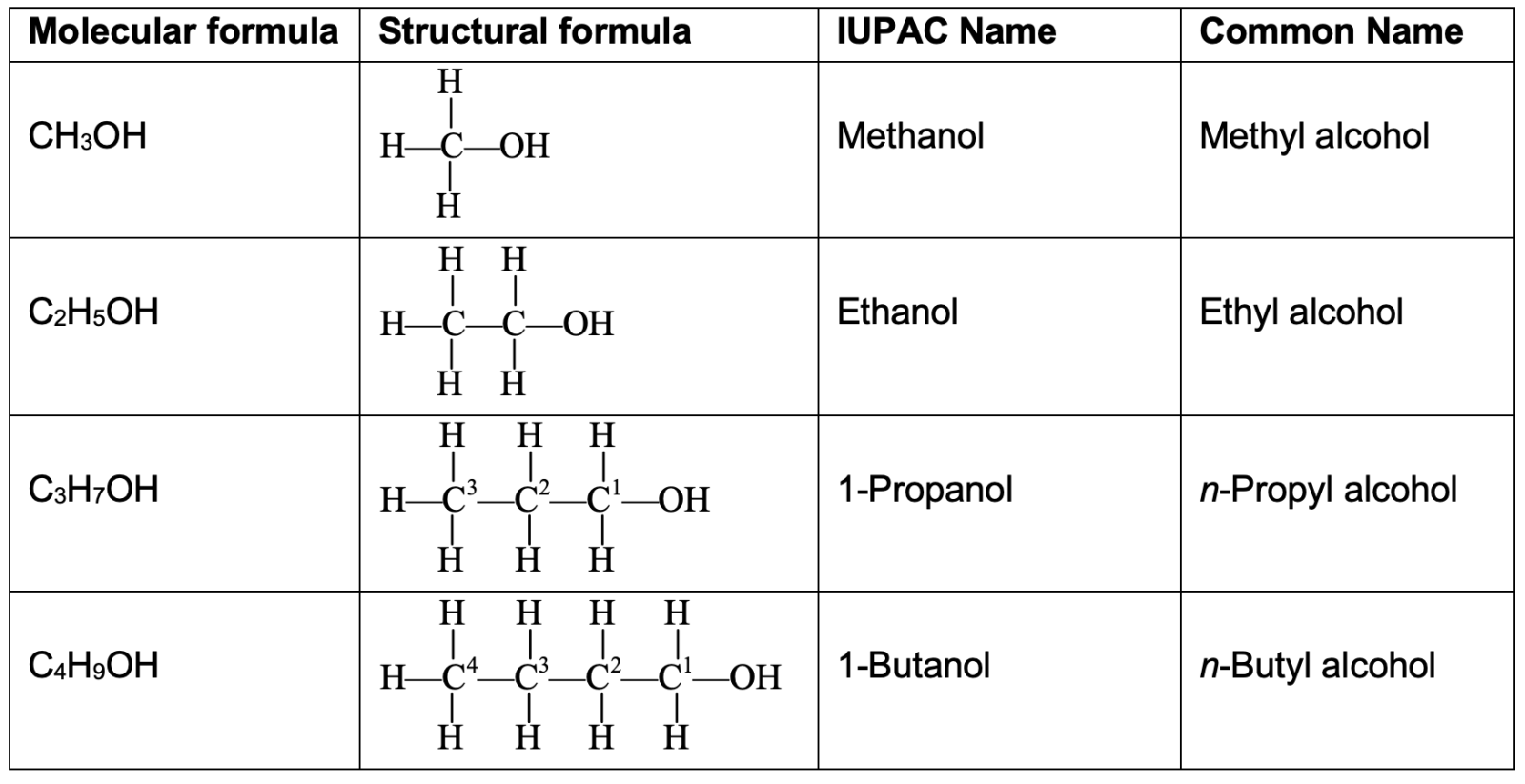

Naming of Alcohols:

There are two methods of naming alcohols:

- Common method: Name of the alkyl group + alcohol

- IUPAC system: According to this system :

(a) Always start numbering from carbon atom of –OH group if it is the end carbon atom in the chain. If the hydroxyl group is not attached to the end carbon atom in the chain, the numbering starts from the end carbon atom in such a way that the carbon atom carrying the hydroxyl group gets the smallest possible number.

(b) ‘e’ of parent alkane is replaced by ‘ol’.

i.e. Alkane –e + ol = Alkanol

For example

CH3OH It contains 1 carbon atom, so its parent alkane is methane, CH4. It also contains an alcohol group (OH group) which is indicated by using ‘ol’ as a suffix or ending. Now, replacing the last ‘e’ of methane by ‘ol’, we get the name methanol (methan + ol = methanol). So, the IUPAC name of CH3OH is methanol.

The common name of methanol is methyl alcohol.

The name and structure of alcohols are summarized in the table below:

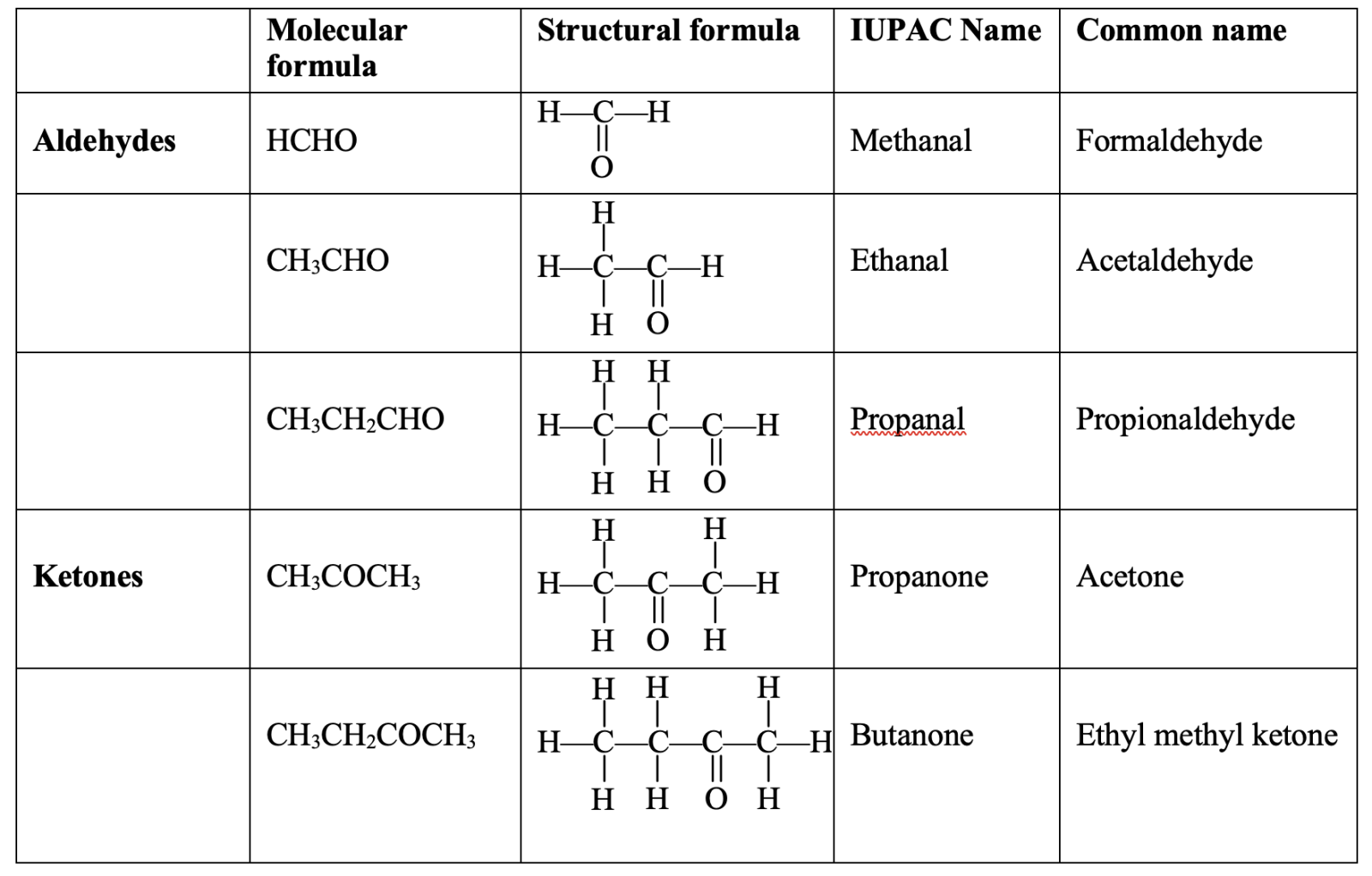

Aldehydes:

Aldehydes are the organic compounds containing an aldehyde group (—CHO group) attached to a carbon atom. The two simple aldehydes are formaldehyde, HCHO (which is also called methanal) and acetaldehyde, CH3CHO (which is also called ethanal). General molecular formula of aldehydes is CnH2nO (where n is the number of carbon atoms in one molecule of the aldehyde). For example, if the number of carbon atoms in an aldehyde is 1, then

n = 1, and its molecular formula will be C1H2×1O or CH2O. This aldehyde must contain an aldehyde group, —CHO, so its chemical formula will be HCHO.

Functional group:

General formula:

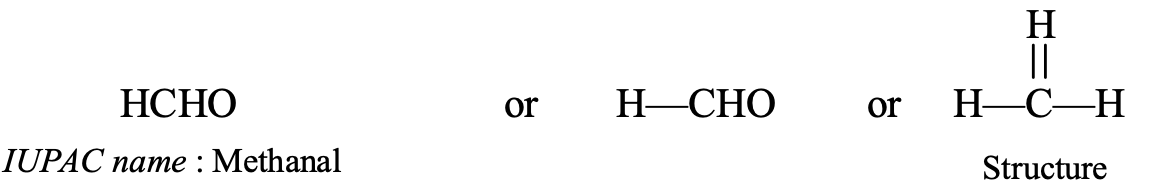

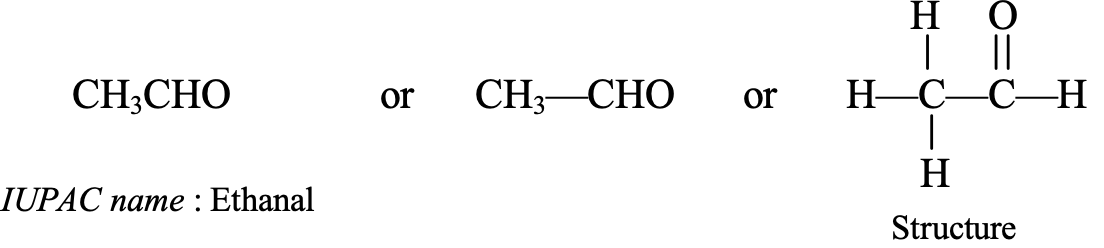

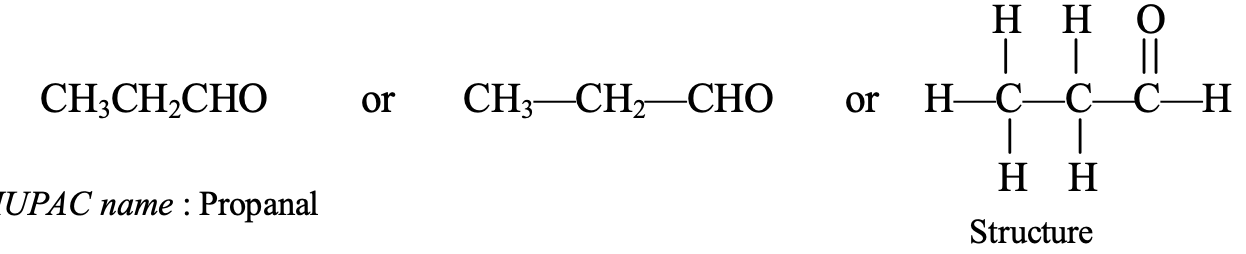

IUPAC Naming of aldehydes:

- Always start numbering from carbon atom of –CHO group.

- ‘e’ of parent alkane is replaced by ‘al’.

i.e. Alkane –e + al = Alkanal

For Example,

- HCHO : It contains 1 carbon atom, so its parent alkane is methane, HCHO also contains an aldehyde group (–CHO group) which is indicated by using ‘al ‘ as suffix or ending. So, replacing the last ‘e’ of methane by ‘al’ we get the name methanal (methan + al = methanal). Thus, the IUPAC name of HCHO is methanal.

The common name of methanal (HCHO) is formaldehyde.

- CH3CHO : It contains two carbon atoms, so its parent hydrocarbon is ethane. Thus, the IUPAC name of CH3CHO is ethanal.

The common name of ethanal (CH3CHO) is acetaldehyde.

- CH3CH2CHO: It contains three carbon atoms, so its parent alkane is propane. Thus, the IUPAC name of CH3CH2CHO is propanal.

The common name of propanal (CH3CH2CHO) is propionaldehyde.

The name and structure of aldehydes are summarized in the table below:

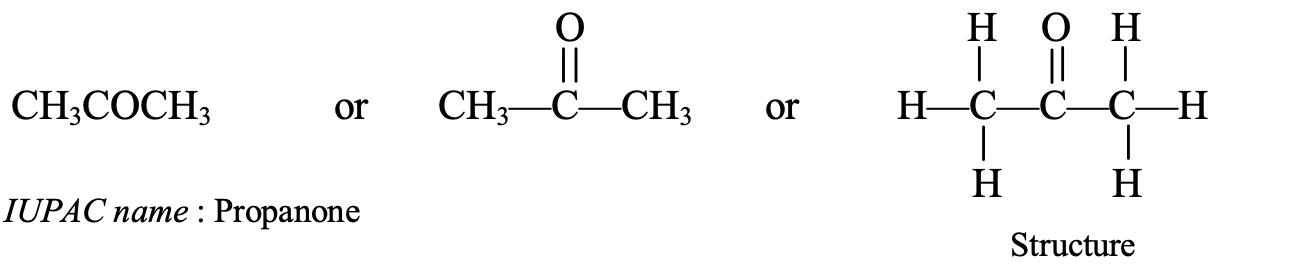

Ketones:

Ketones are the carbon compounds (or organic compounds) containing the ketone group, —CO— group. Ketone group always occurs in the middle of a carbon chain, so a ketone must contain at least three carbon atoms in its molecule, one carbon atom of the ketone group and two carbon atoms on its two sides. There can be no ketone with less than three carbon atoms in it. The simplest ketone is acetone, CH3COCH3 (which is also known as propanone).

IUPAC Naming

- ‘e’ of the parent alkane is replaced by ‘one’.

So, IUPAC Name : Alkane –e + one = Alkanone

- Minimum numbering is given to the carbonyl group.

For Example,

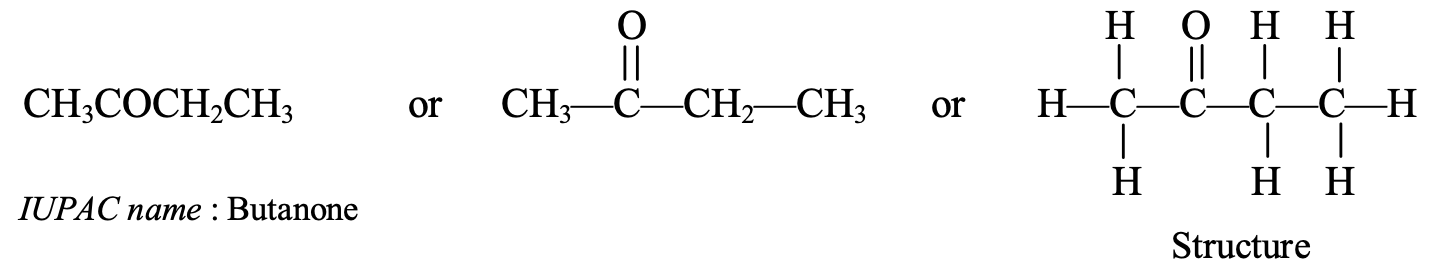

- CH3COCH3: This contains three carbon atoms, so its parent alkane is propane. Thus, its IUPAC name is propanone. Its common name is acetone. Propanone is the simplest ketone.

- CH3COCH2CH3: This compound contains 4 carbon atoms, so its parent alkane is butane. Thus, the IUPAC name of the compound CH3COCH2CH3 is butanone.

The common name of butanone is ethyl methyl ketone.

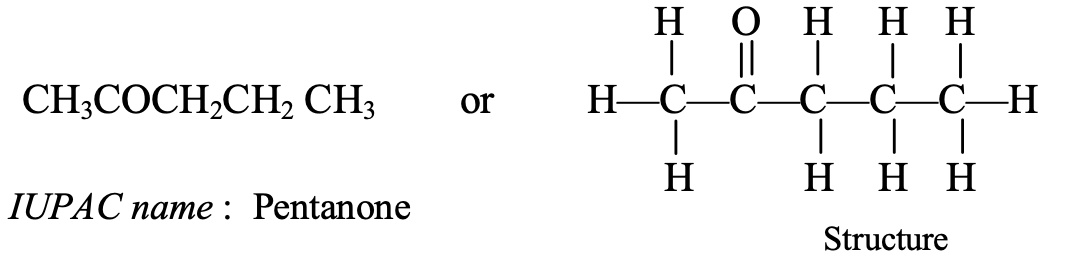

- CH3COCH2CH2CH3: This compound contains 5 carbon atoms, so its parent alkane is pentane. Thus, the IUPAC name of the compound CH3COCH2CH2CH3 is pentanone.

The common name of pentanone is methyl propyl ketone.

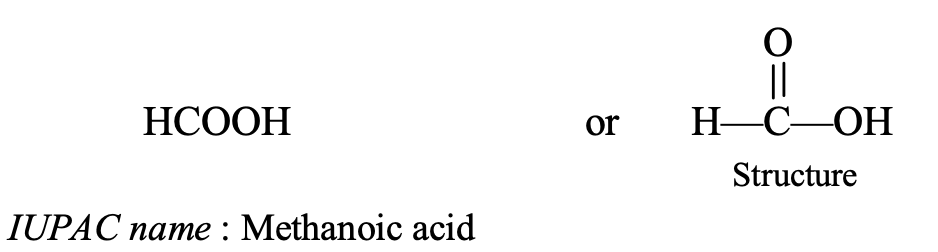

CARBOXYLIC ACIDS:

Carboxylic acids are a class of organic compounds which contain carboxyl group (—COOH) as the functional group. This group is structurally represented as - C = O - OH . Thus, carboxyl group is a combination of the carbonyl ( -C = O -) and the hydroxyl (–OH) groups.

Formerly, higher members of the carboxylic acids were obtained from fats. Hence, these acids are also called fatty acids.

Functional group: —COOH

General formula: R—COOH

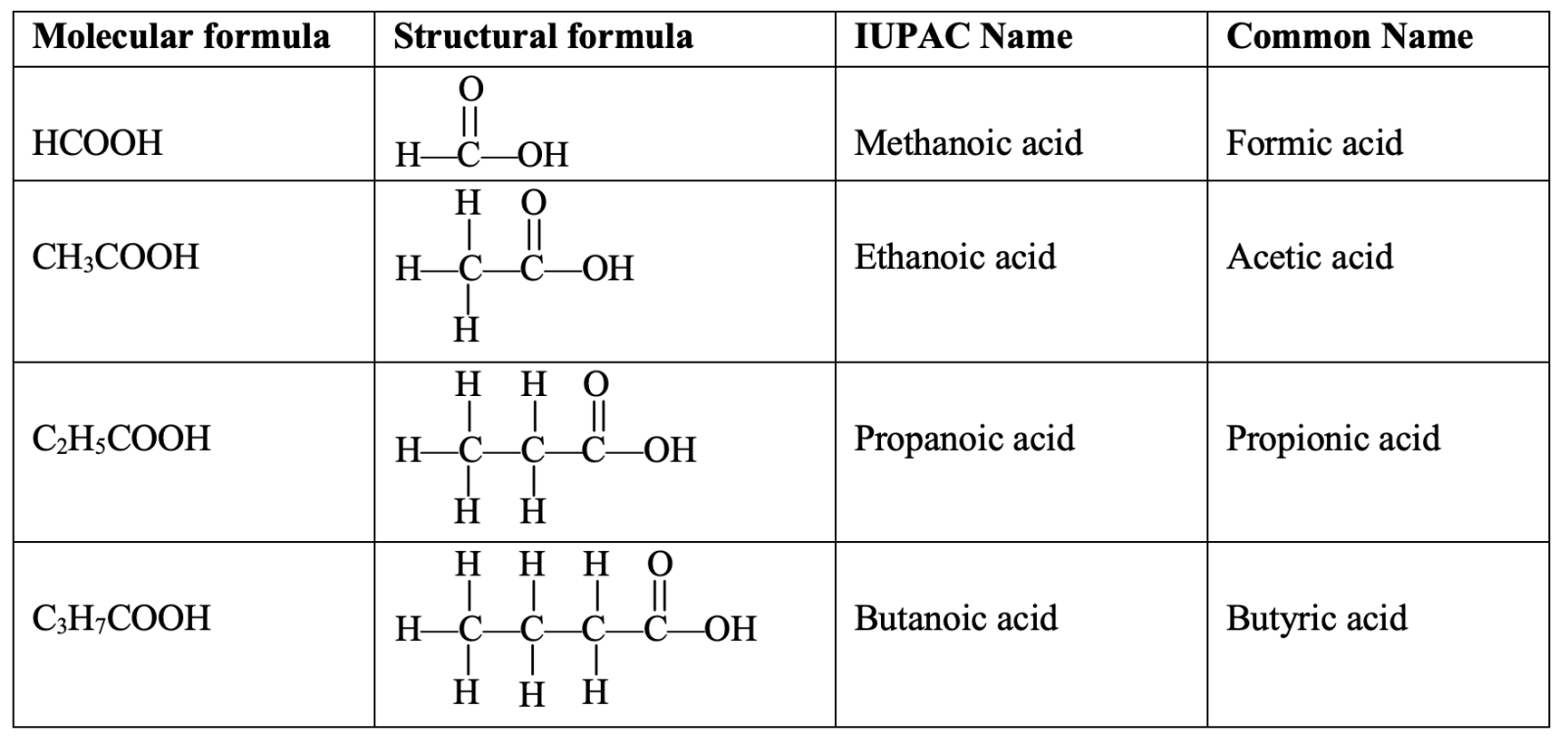

Nomenclature of carboxylic Acids

- Common names

Common names of carboxylic acids have originated from the Latin or the Greek names of the sources from which the acids are obtained.

| Formula | Occurrence | Latin or Greek names of the source | Name of acid |

| 1. HCOOH | Ants | Ants are called formica in Latin | Formic acid |

| 2. CH3COOH | Vinegar | Vinegar is called acetum in Latin | Acetic acid |

| 3. CH3CH2COOH | Butter | Butter is called butyrum in Latin | Butyric acid |

- IUPAC names

In IUPAC system, naming of carboxylic acids is done by replacing the end –e of the corresponding hydrocarbon by –oic acid. The first four acids with the corresponding hydro carbons are given below in the table :

|

Formula of acid |

Number of carbon atoms | Corresponding hydrocarbon | IUPAC name |

| 1. HCOOH | 1 | Methane (CH4) | Methanoic acid |

| 2. CH3COOH | 2 | Ethane (C2H6) | Ethanoic acid |

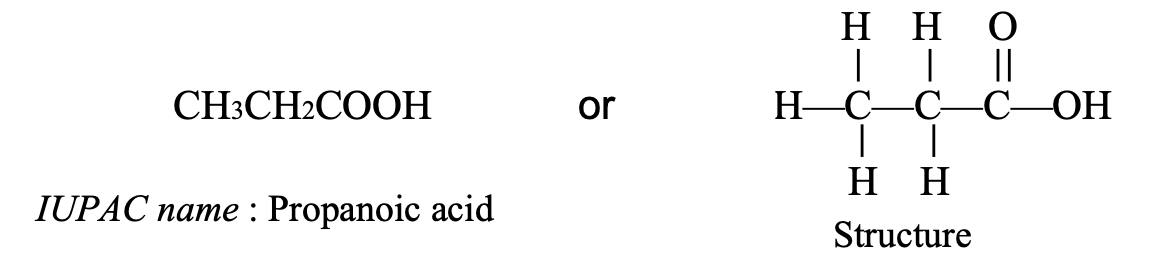

| 3. CH3CH2COOH | 3 | Propane (C3H8) | Propanoic acid |

| 4. CH3CH2CH2COOH | 4 | Butane (C4H10) | Butanoic acid |

So, IUPAC Name : Alkane –e + oic acid = Alkanoic acid

The positions of the substituents are shown by allotting numbers to the carbon atoms to which the substituted groups are linked. The numbering of carbon atoms starts from the carbon atom of the carboxyl group.

For example,

- HCOOH : This compound contains 1 carbon atom so its parent alkane is methane. It also contains a carboxylic acid group (—COOH group). The name of this compound can be obtained by replacing the last ‘e’ of methane by ‘oic acid’ so it becomes methanoic acid (methan + oic acid = methanoic acid). Thus, the IUPAC name of HCOOH is methanoic acid.

- CH3COOH : This compound contains 2 carbon atoms so its parent alkane is ethane.

Thus, the IUPAC name of CH3COOH is ethanoic acid.

The common name of ethanoic acid (CH3COOH) is acetic acid.

- CH3CH2COOH: This compound contains 3 carbon atoms, so its parent alkane is propane. So, the IUPAC name of CH3CH2COOH is propanoic acid.

The structure and IUPAC names of carboxylic acids are summarized below in the table:

COAL AND PETROLEUM

A fuel is a material that has energy stored inside it. When a fuel is burned, the energy is released mainly as heat (and some light). This heat energy can be used for various purposes like cooking food, heating water, and for running generators in thermal power stations, machines in factories and engines of motor cars. Most of the common fuels are either free carbon or carbon compounds. For example, the fuels such as coal, coke and charcoal contain free carbon whereas the fuels such as kerosene, petrol, LPG and natural gas, are all carbon compounds.

When carbon in any form (coal, coke, charcoal, etc.) is burned in the oxygen (of air), it forms carbon dioxide gas and releases a large amount of heat and some light: