Metals and Non-Metals: A Complete Scientific Guide

The classification of chemical elements into metals and non-metals forms the foundation of inorganic chemistry. Of the 118 known chemical elements, the majority are metals, with only 22 classified as non-metals. This fundamental distinction is based on physical properties, chemical behavior, and electronic configuration. Understanding these differences is crucial for students preparing for competitive examinations like NTSE and for grasping essential concepts in materials science and industrial chemistry.

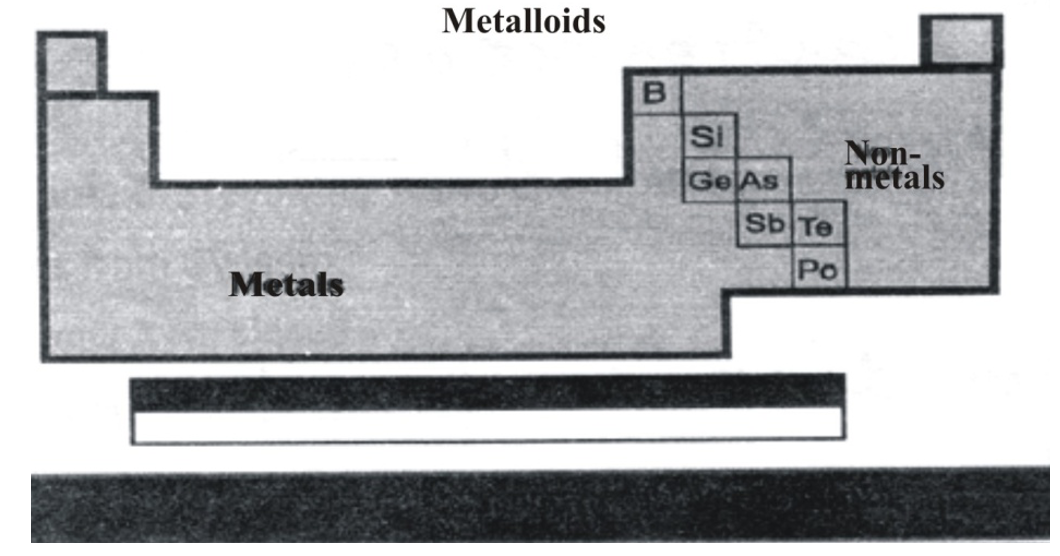

Fundamental Classification and Position in the Periodic Table

Metals occupy the left side and center of the periodic table, while non-metals are positioned on the right side. A zig-zag line separates these two categories, with elements adjacent to this boundary exhibiting properties of both groups these are called metalloids or semi-metals. Common metalloids include Boron (B), Silicon (Si), Germanium (Ge), Arsenic (As), Antimony (Sb), Tellurium (Te), and Polonium (Po).

An important trend to note is that metallic character decreases from left to right across a period, while it increases down a group. This pattern is directly related to the electronic configuration and the tendency of atoms to lose or gain electrons.

Hydrogen presents an interesting exception: though it is a non-metal, it is placed on the left side of the periodic table due to its single valence electron, similar to alkali metals.

Physical Properties of Metals: Strength, Conductivity, and Malleability

Metals exhibit a distinctive set of physical properties that make them invaluable for construction, electrical applications, and manufacturing:

State and Physical Appearance

All metals except mercury exist as solids at room temperature. Mercury (Hg) is the only liquid metal under standard conditions. Metals possess metallic luster a characteristic shine that can be enhanced through polishing. Gold, silver, and copper are particularly noted for their brilliant luster.

Malleability and Ductility

Malleability refers to the ability of metals to be hammered into thin sheets without breaking. Gold and silver are among the most malleable metals, followed by aluminum and copper. Ductility describes the capacity to be drawn into thin wires gold and silver again lead, with copper and aluminum being extensively used in electrical wiring due to their excellent ductility.

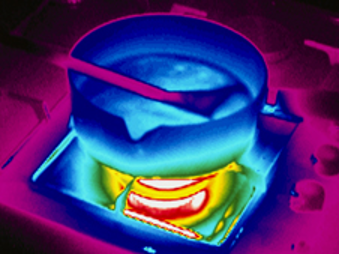

Electrical and Thermal Conductivity

Metals are excellent conductors of heat and electricity due to the presence of free electrons that can move throughout the metallic structure. Silver is the best conductor of both heat and electricity, followed by copper and aluminum. This property makes copper and aluminum the materials of choice for electrical wiring and heat transfer applications. Lead and mercury, however, are poor conductors of heat among metals.

Density and Hardness

Most metals have high densities and are relatively heavy. Mercury has an exceptionally high density of 13.6 g/cm³. Exceptions include sodium, potassium, magnesium, and aluminum, which have lower densities. Regarding hardness, most metals are hard substances—iron, copper, and aluminum cannot be cut with a knife. Sodium and potassium are notable exceptions, being soft enough to cut with a knife.

Melting and Boiling Points

Metals generally possess high melting and boiling points, requiring significant energy to change their state. Tungsten has the highest melting point among all metals at 3430°C, making it ideal for light bulb filaments. However, sodium and potassium have relatively low melting points.

Sonorous Nature

Metals are sonorous they produce a ringing sound when struck. This property is utilized in making bells and musical instruments.

Physical Properties of Non-Metals: Diversity in States and Poor Conductivity

Non-metals exhibit vastly different physical properties compared to metals:

State and Diversity

Non-metals exist in all three states at room temperature: solids (carbon, sulfur, phosphorus, iodine), liquids (bromine—the only liquid non-metal), and gases (hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, chlorine, and others). This diversity reflects the weak intermolecular forces between non-metal molecules.

Brittleness and Lack of Malleability

Non-metals are typically brittle when solid they break easily when hammered rather than forming sheets. They are neither malleable nor ductile. Diamond (a form of carbon) is an important exception, being the hardest naturally occurring substance.

Poor Conductivity

Non-metals are generally poor conductors of heat and electricity. The major exception is graphite (another form of carbon), which conducts electricity and is used in electrodes. Iodine is also an exception regarding luster, as it exhibits a metallic-like shine.

Low Density and Melting Points

Non-metals typically have low densities and are lighter than metals. They also possess low melting and boiling points, with graphite, boron, carbon, and silicon being notable exceptions. Non-metals are not sonorous and do not produce sound when struck.

Electronic Configuration and Chemical Behavior

The fundamental difference in chemical behavior between metals and non-metals stems from their electronic configuration:

Metals: Electropositive Elements

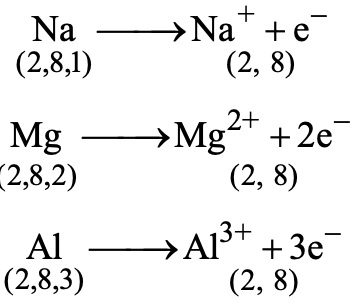

Metals typically have 1 to 3 electrons in their outermost shell (valence shell). They readily lose these electrons to form positive ions (cations) and achieve a stable noble gas configuration. For example:

- Sodium (2,8,1) loses one electron → Na⁺ (2,8)

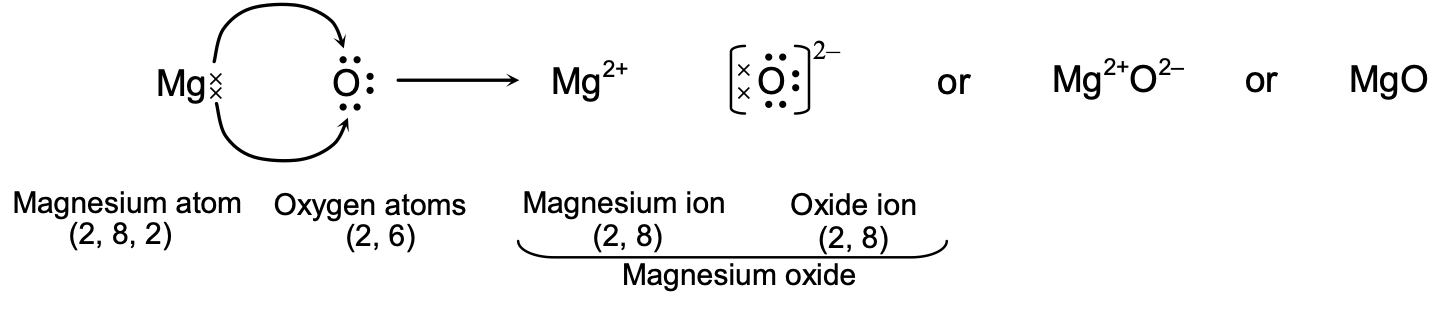

- Magnesium (2,8,2) loses two electrons → Mg²⁺ (2,8)

- Aluminum (2,8,3) loses three electrons → Al³⁺ (2,8)

This tendency to lose electrons makes metals electropositive and reducing agents in chemical reactions.

Non-Metals: Electronegative Elements

Non-metals typically have 4 to 8 electrons in their outermost shell. They gain electrons to form negative ions (anions) and complete their octet. For example:

- Chlorine (2,8,7) gains one electron → Cl⁻ (2,8,8)

- Oxygen (2,6) gains two electrons → O²⁻ (2,8)

- Nitrogen (2,5) gains three electrons → N³⁻ (2,8)

This tendency to gain electrons makes non-metals electronegative and oxidizing agents in chemical reactions.

Chemical Properties of Metals: Reactions and Activity Series

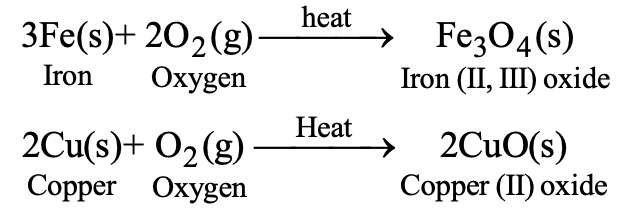

Reaction with Oxygen

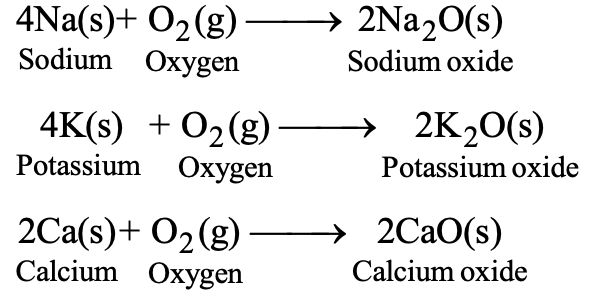

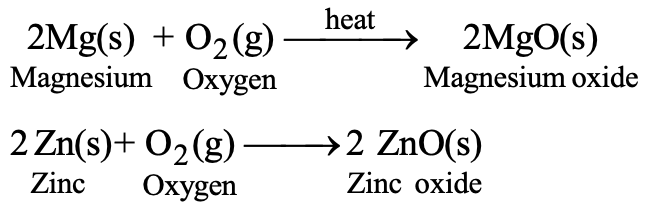

Metals react with oxygen to form metal oxides, which are generally basic in nature. The reactivity varies:

- Highly reactive metals (sodium, potassium, calcium) react with oxygen even at room temperature

- Moderately reactive metals (magnesium, zinc) require heating

- Less reactive metals (iron, copper) react only on prolonged heating

Example: 4Na(s) + O₂(g) → 2Na₂O(s)

When metal oxides dissolve in water, they form alkaline solutions that turn red litmus blue.

Reaction with Water

The reactivity of metals with water varies significantly:

- Sodium and potassium react vigorously with cold water, producing metal hydroxide and hydrogen gas

- Calcium reacts less violently with cold water

- Magnesium reacts slowly with cold water but rapidly with hot water

- Zinc and aluminum react only with steam

- Iron reacts with steam only when red hot

- Copper, silver, and gold do not react with water under any conditions

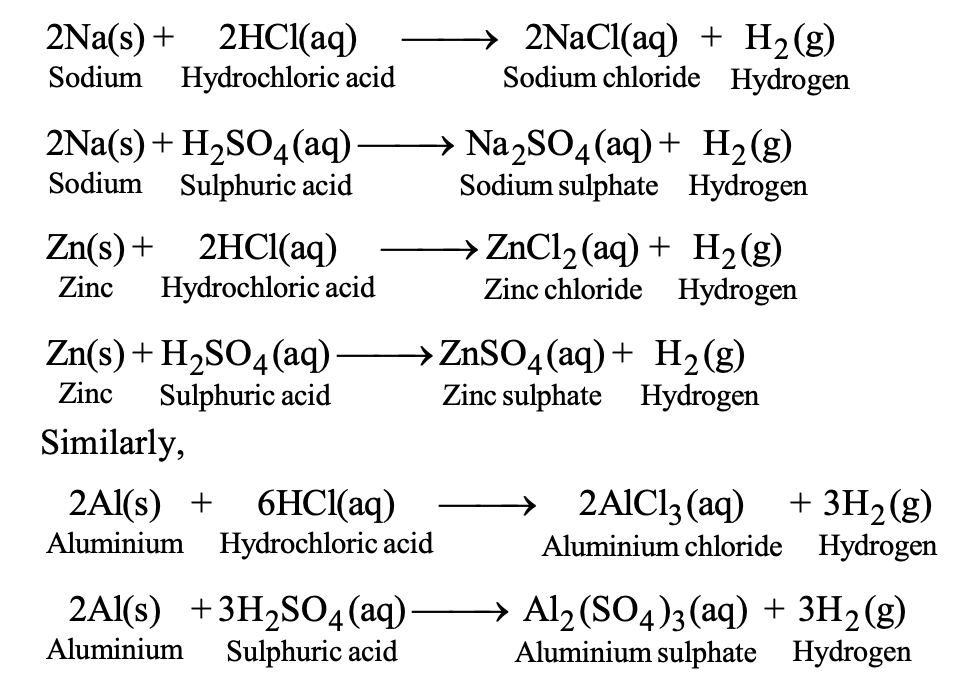

Reaction with Dilute Acids

Metals above hydrogen in the reactivity series displace hydrogen from dilute acids, producing metal salts and hydrogen gas:

Zn(s) + 2HCl(aq) → ZnCl₂(aq) + H₂(g)

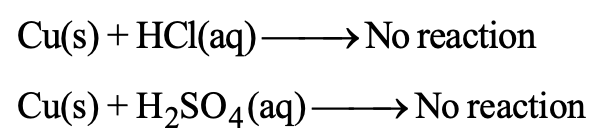

Metals below hydrogen (copper, silver, gold) do not liberate hydrogen from dilute acids.

Displacement Reactions

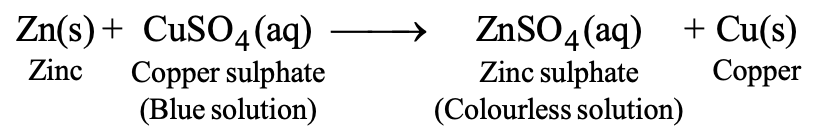

A more reactive metal can displace a less reactive metal from its salt solution.

For example:

Zn(s) + CuSO₄(aq) → ZnSO₄(aq) + Cu(s)

This principle forms the basis of the reactivity series or activity series of metals.

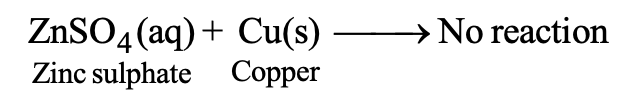

The Reactivity Series: Arranging Metals by Chemical Activity

The reactivity series arranges metals in order of decreasing reactivity:

Most Reactive:

- Lithium (Li)

- Potassium (K)

- Barium (Ba)

- Sodium (Na)

- Calcium (Ca)

- Magnesium (Mg)

- Aluminum (Al)

- Zinc (Zn)

- Iron (Fe)

- Nickel (Ni)

- Tin (Sn)

- Lead (Pb)

- Hydrogen (H) [reference point]

- Copper (Cu)

- Mercury (Hg)

- Silver (Ag)

- Gold (Au)

- Platinum (Pt)

Least Reactive

Significance of the Reactivity Series

- Metals above hydrogen are more reactive than hydrogen and can displace it from acids and water

- Metals below hydrogen are less reactive and cannot displace hydrogen

- A metal higher in the series can displace a metal lower in the series from its salt solution

- Metals at the top are very reactive and do not occur free in nature

- Metals at the bottom are least reactive and often occur in the free state (gold, platinum)

Chemical Properties of Non-Metals: Acidic Oxides and Oxidizing Nature

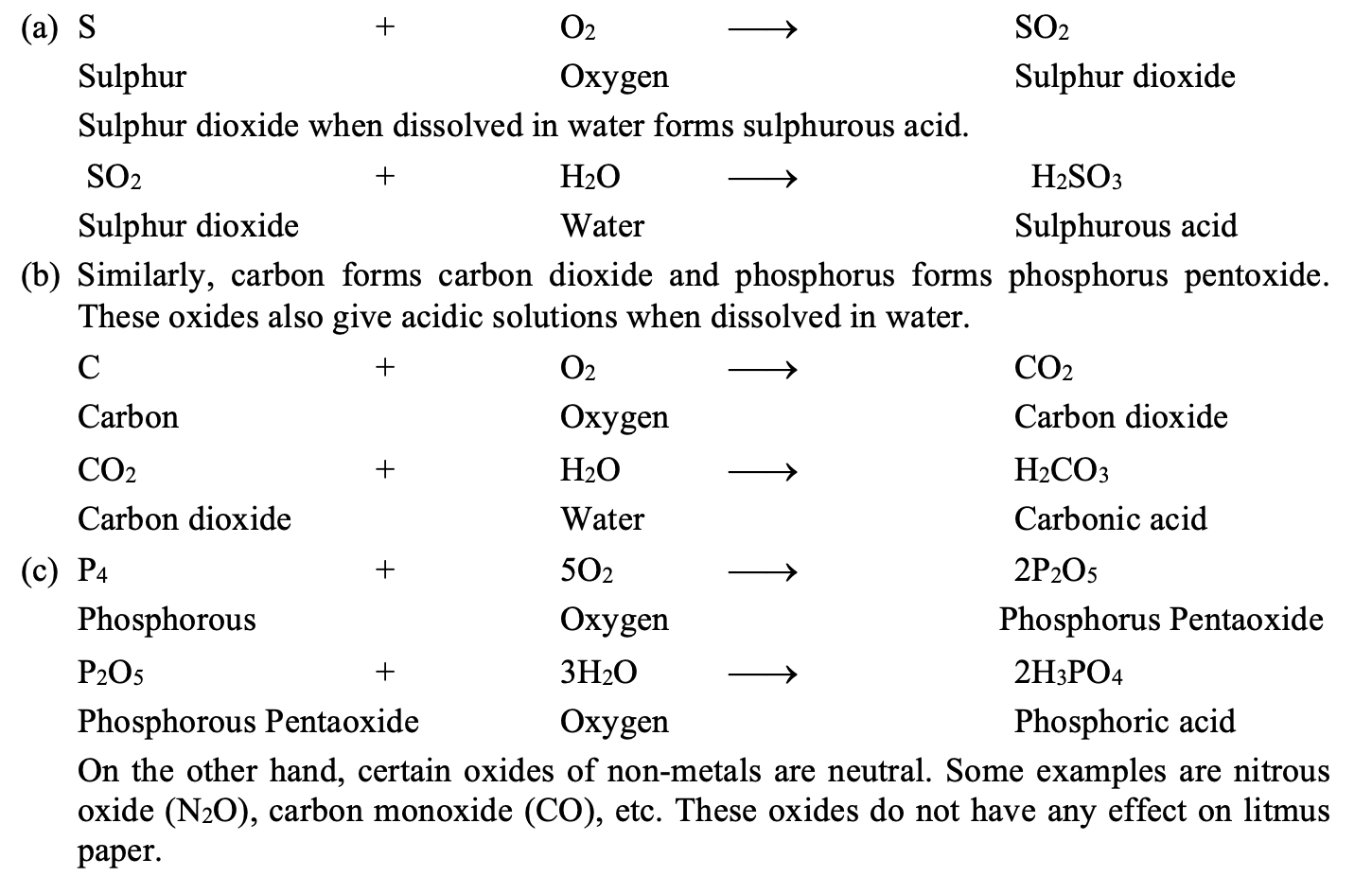

Reaction with Oxygen

Non-metals react with oxygen to form non-metal oxides, which are typically acidic in nature and covalent compounds. When dissolved in water, they form acidic solutions that turn blue litmus red.

Examples:

- S + O₂ → SO₂ (sulfur dioxide)

- SO₂ + H₂O → H₂SO₃ (sulfurous acid)

- C + O₂ → CO₂ (carbon dioxide)

- CO₂ + H₂O → H₂CO₃ (carbonic acid)

Some non-metal oxides like CO and N₂O are neutral and do not affect litmus.

Reaction with Water and Acids

Non-metals generally do not react with water or acids because they cannot lose electrons to reduce H⁺ ions to hydrogen gas. Being electronegative, non-metals tend to gain rather than donate electrons.

Reaction with Chlorine and Hydrogen

Non-metals react with chlorine to form covalent chlorides (HCl, PCl₃, PCl₅) and with hydrogen to form covalent hydrides (H₂O, NH₃, CH₄, H₂S).

Oxidizing Nature

Non-metals act as oxidizing agents due to their strong tendency to accept electrons. Fluorine is the strongest oxidizing agent among all non-metals.

Chemical Bonding: Ionic and Covalent Bonds

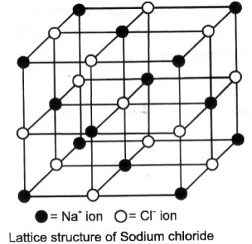

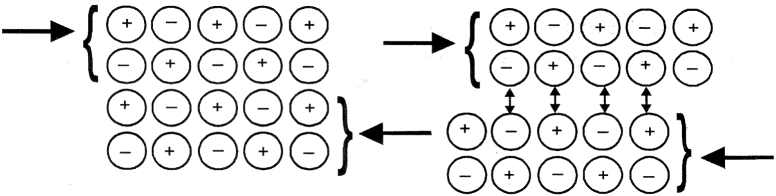

Ionic Bonds: Transfer of Electrons

An ionic bond (or electrovalent bond) forms through the complete transfer of electrons from a metal atom to a non-metal atom. The resulting oppositely charged ions are held together by strong electrostatic forces.

Formation of Sodium Chloride (NaCl):

- Na (2,8,1) loses one electron → Na⁺ (2,8)

- Cl (2,8,7) gains one electron → Cl⁻ (2,8,8)

- Na⁺ and Cl⁻ combine → NaCl

Properties of Ionic Compounds:

- Solid and hard at room temperature due to strong electrostatic forces

- High melting and boiling points requiring significant energy to break the crystal lattice

- Conduct electricity when molten or dissolved in water (free ions can move)

- Soluble in water but insoluble in organic solvents

- Brittle - break when force is applied due to repulsion between like charges

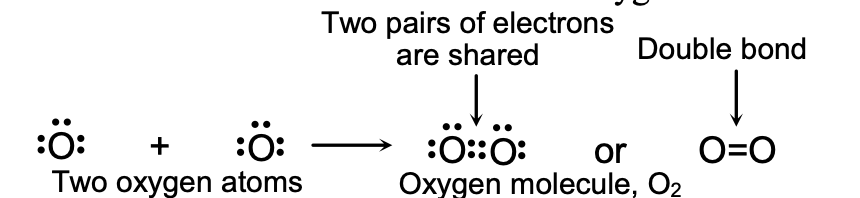

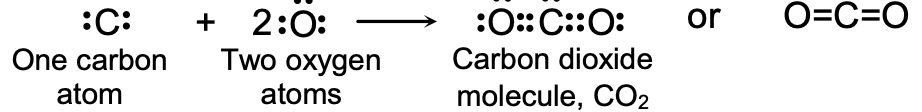

Covalent Bonds: Sharing of Electrons

A covalent bond forms through the sharing of electrons between two non-metal atoms, allowing each to achieve a stable electronic configuration.

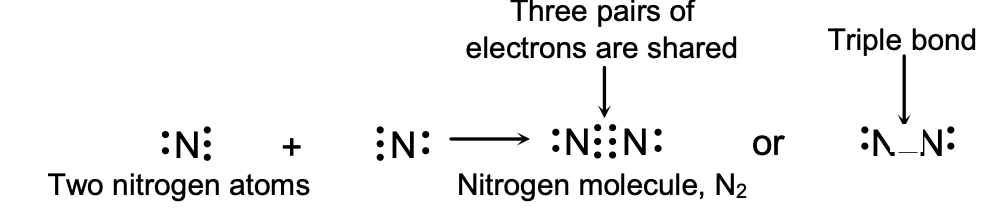

Types of Covalent Bonds:

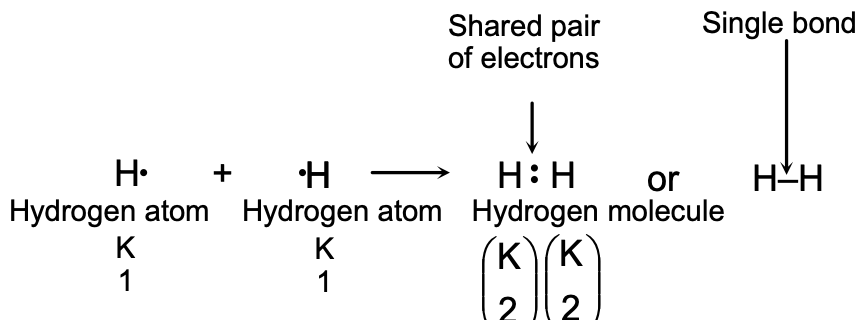

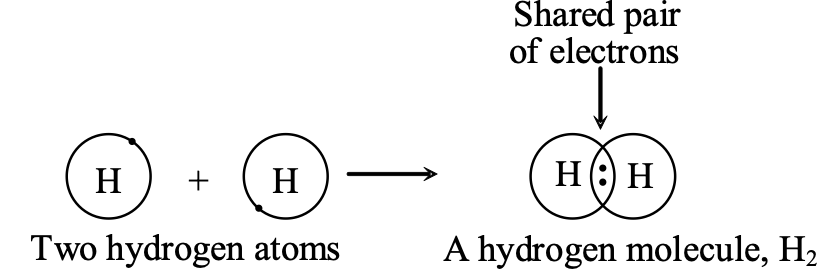

- Single Bond: Sharing of one pair of electrons (H-H in H₂)

- Double Bond: Sharing of two pairs of electrons (O=O in O₂)

- Triple Bond: Sharing of three pairs of electrons (N≡N in N₂)

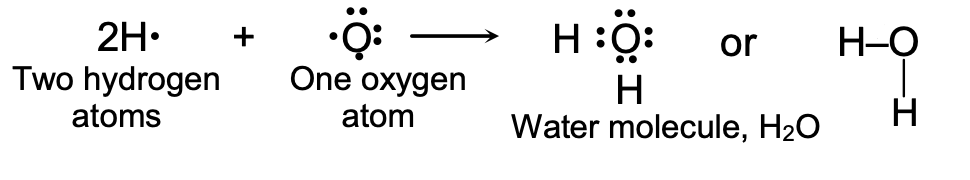

Formation of Water (H₂O):

- Each H atom (1 electron) shares its electron with O atom (2,6)

- O shares two of its electrons with two H atoms

- Result: H₂O molecule with two single covalent bonds

Properties of Covalent Compounds:

- Usually liquids or gases at room temperature (weak intermolecular forces)

- Low melting and boiling points compared to ionic compounds

- Do not conduct electricity (no ions present)

- Insoluble in water but soluble in organic solvents (with exceptions like glucose, sugar, urea)

- Soft when solid

Occurrence and Extraction of Metals: Metallurgy

Occurrence of Metals

Metals occur in Earth's crust either in free state (native state) or in combined state:

Free State: Unreactive metals like gold, silver, platinum, and sometimes copper occur in elemental form because they do not readily react with atmospheric oxygen, moisture, or carbon dioxide.

Combined State: Most metals exist as compounds—oxides, carbonates, sulfides, sulfates, silicates, or halides. Reactive metals like sodium, magnesium, calcium, aluminum, iron, and zinc always occur in combined state.

Minerals and Ores

Minerals are naturally occurring inorganic compounds in Earth's crust. Ores are minerals from which metals can be profitably extracted. All ores are minerals, but not all minerals are ores.

For example, aluminum occurs in bauxite (Al₂O₃·2H₂O) and china clay (Al₂O₃·2SiO₂·2H₂O), but bauxite is the preferred ore because extraction is more economical.

Gangue refers to the unwanted sand and rocky impurities present in ores.

Common Types of Ores

| Ore Type | Metal | Ore Name | Composition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxide | Aluminum | Bauxite | Al₂O₃·2H₂O |

| Oxide | Iron | Haematite | Fe₂O₃ |

| Oxide | Iron | Magnetite | Fe₃O₄ |

| Sulfide | Copper | Copper Pyrites | CuFeS₂ |

| Sulfide | Zinc | Zinc Blende | ZnS |

| Sulfide | Lead | Galena | PbS |

| Sulfide | Mercury | Cinnabar | HgS |

| Carbonate | Calcium | Limestone | CaCO₃ |

| Carbonate | Zinc | Calamine | ZnCO₃ |

| Halide | Sodium | Rock Salt | NaCl |

| Halide | Calcium | Fluorspar | CaF₂ |

Metallurgy: The Extraction Process

Metallurgy is the science and technology of extracting metals from ores and refining them. The process typically involves these steps:

1. Crushing and Grinding (Pulverization)

Ore lumps are crushed into smaller pieces using crushers, then ground into fine powder using ball mills or stamp mills to increase surface area for subsequent processes.

2. Concentration or Enrichment of Ore

The removal of gangue (unwanted impurities) from ore is called concentration or ore dressing. Methods include:

a) Hydraulic Washing: Based on density differences; lighter gangue particles are washed away by water, leaving heavier ore particles. Used for oxide ores.

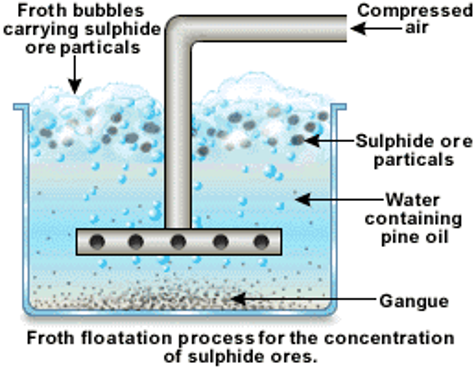

b) Froth Floatation: Used for sulfide ores (copper, zinc, lead). The powdered ore is mixed with water and pine oil. Air is blown through the mixture, creating froth that carries the sulfide ore particles to the surface (preferentially wetted by oil), while gangue sinks.

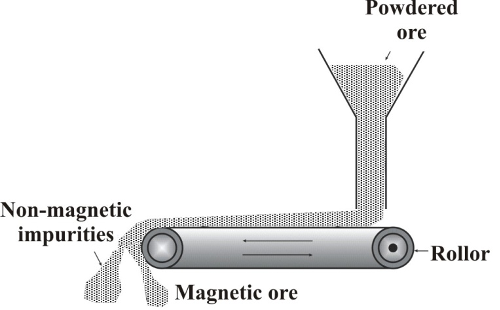

c) Magnetic Separation: Used for magnetic ores like iron. Ore powder is dropped on a moving belt passing over a magnetic roller. Magnetic ore particles are attracted and separated from non-magnetic gangue.

d) Chemical Separation: Based on chemical property differences. Example: Baeyer's method for purifying bauxite using sodium hydroxide to form soluble sodium aluminate, leaving iron oxide impurities behind.

3. Conversion to Metal Oxide

a) Calcination: Heating the concentrated ore in the absence of air to:

- Convert carbonate ores to metal oxides (ZnCO₃ → ZnO + CO₂)

- Remove water from hydrated ores (Al₂O₃·2H₂O → Al₂O₃ + 2H₂O)

- Remove volatile impurities

b) Roasting: Heating the concentrated ore in the presence of excess air to:

- Convert sulfide ores to metal oxides (2ZnS + 3O₂ → 2ZnO + 2SO₂)

- Remove moisture and volatile impurities

4. Reduction to Metal

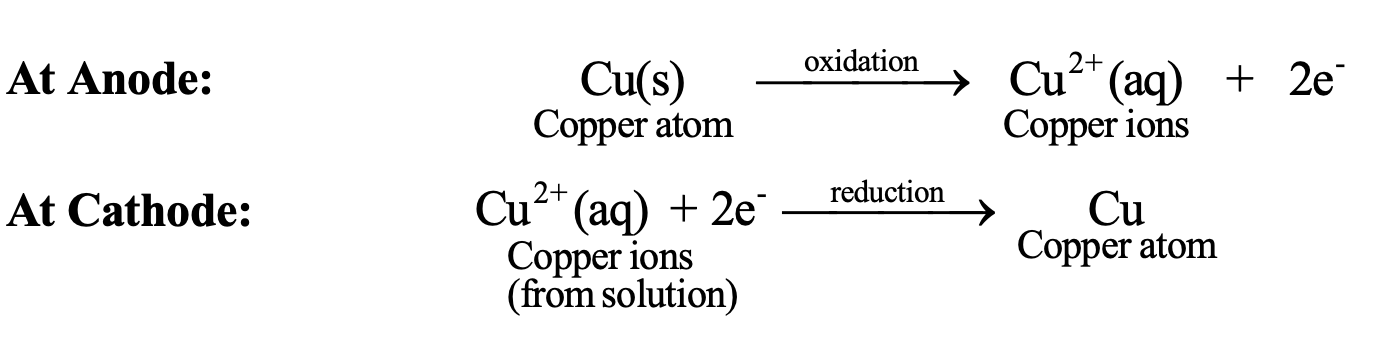

The method depends on the metal's position in the reactivity series:

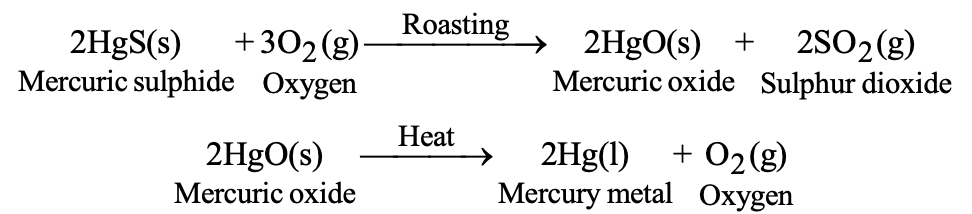

a) Reduction by Heating: For metals low in reactivity series (mercury, copper):

- 2HgO(s) → 2Hg(l) + O₂(g) (heating alone)

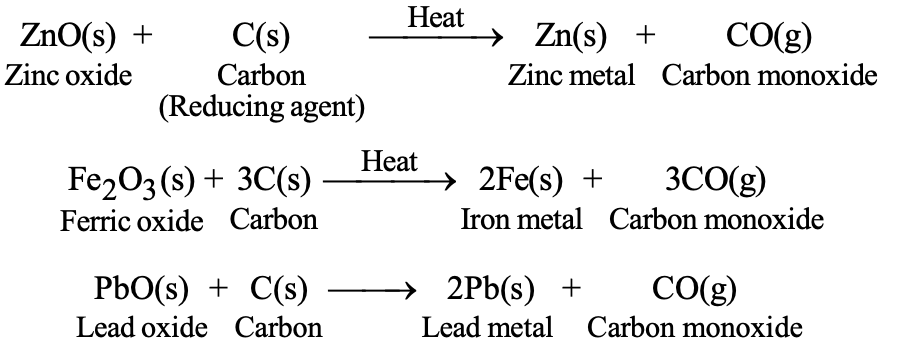

b) Reduction with Carbon: For moderately reactive metals (zinc, iron, lead, copper):

- ZnO(s) + C(s) → Zn(s) + CO(g)

- Fe₂O₃(s) + 3C(s) → 2Fe(s) + 3CO(g)

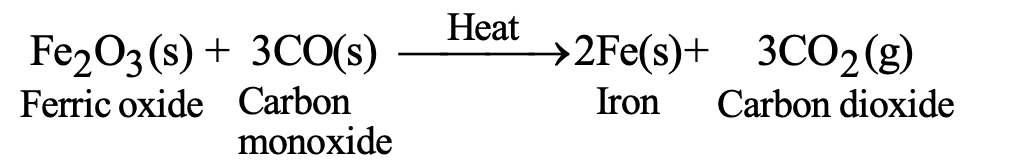

c) Reduction with Carbon Monoxide:

- Fe₃O₄(s) + 4CO(g) → 3Fe(s) + 4CO₂(g)

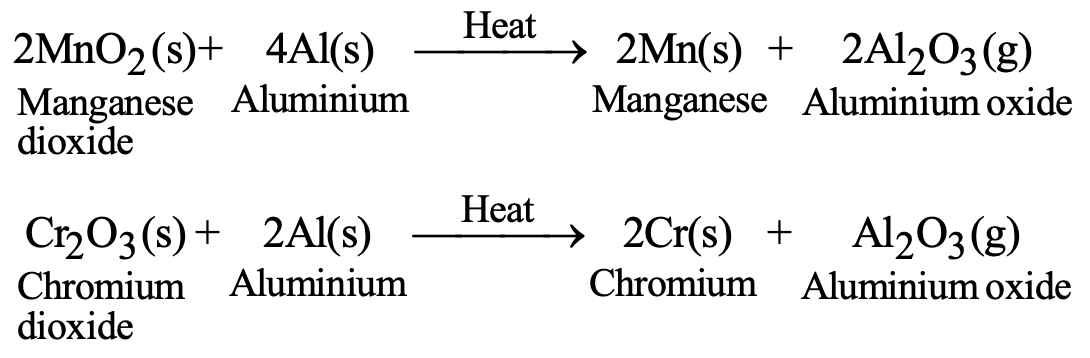

d) Reduction with Aluminum (Thermite Process): For certain metal oxides:

- Cr₂O₃(s) + 2Al(s) → 2Cr(s) + Al₂O₃(g)

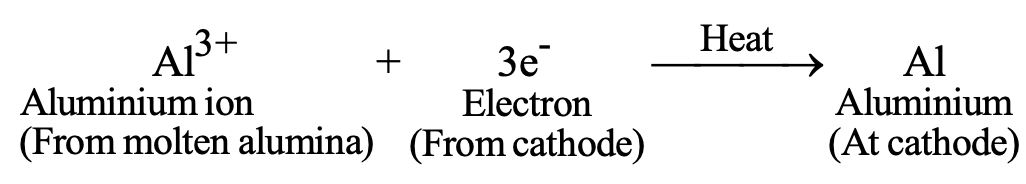

e) Electrolytic Reduction: For highly reactive metals (sodium, calcium, magnesium, aluminum):

- Al₂O₃ (molten) → 2Al (at cathode) + 3/2 O₂ (at anode)

5. Refining or Purification

The extracted metal contains impurities and must be purified:

a) Liquation: For low-melting metals (tin, lead). Impure metal is heated on a sloping hearth slightly above its melting point; pure metal flows down while impurities remain.

b) Distillation: For volatile metals (mercury, zinc). Impure metal is heated in a retort; pure metal distills over and condenses in a receiver.

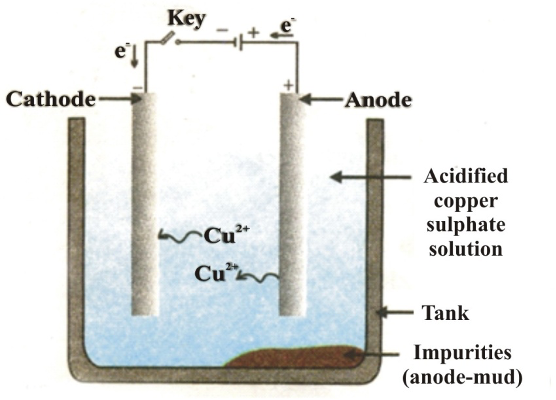

c) Electrolytic Refining: Most widely used for copper, zinc, nickel, silver, gold. Impure metal forms the anode, pure metal strip forms the cathode, and metal salt solution is the electrolyte. Pure metal deposits on the cathode while impurities collect as anode mud.

Example - Electrolytic Refining of Copper:

- Anode: Impure copper block

- Cathode: Thin strip of pure copper

- Electrolyte: Acidified copper sulfate solution

- At anode: Cu(s) → Cu²⁺(aq) + 2e⁻

- At cathode: Cu²⁺(aq) + 2e⁻ → Cu(s)

- Less reactive impurities (Ag, Au) settle as anode mud; more reactive impurities (Fe) dissolve in solution

Corrosion of Metals: Understanding and Prevention

What is Corrosion?

Corrosion is the slow destruction of metals due to their conversion into oxides, carbonates, sulfides, or other compounds through reaction with atmospheric gases (oxygen, carbon dioxide) and moisture. It weakens metal structures and causes significant economic losses.

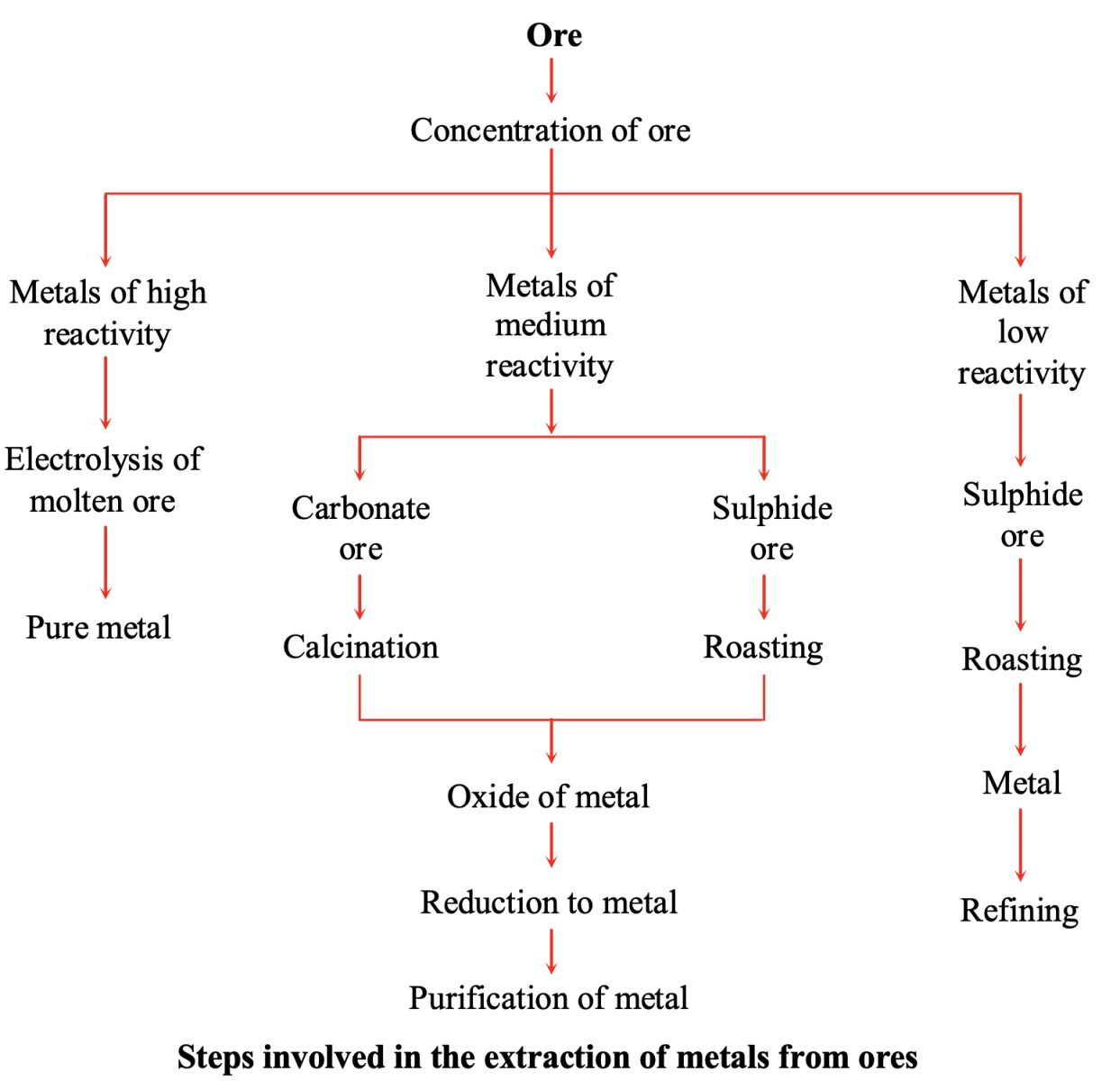

Rusting of Iron

Rusting is the corrosion of iron, producing hydrated iron(III) oxide (Fe₂O₃·xH₂O), commonly called rust—a reddish-brown flaky substance. Rusting requires both air (oxygen) and water (moisture).

Experimental Evidence:

- Iron nail in dry air (with anhydrous CaCl₂): No rust

- Iron nail in air-free boiled water: No rust

- Iron nail in presence of both air and water: Rust forms

This confirms that rusting occurs only when both oxygen and water are present simultaneously.

Prevention of Rusting

- Painting: Applying paint coats isolates iron from air and moisture. Used for railings, bridges, vehicles, and structures.

- Applying Grease or Oil: Creates a protective barrier. Used for tools and machine parts.

- Galvanization: Coating iron with a thin layer of zinc (more reactive than iron). Zinc forms a protective layer of basic zinc carbonate that prevents further corrosion. Used for buckets, water pipes, and roofing sheets.

- Tin-Plating and Chromium-Plating: Electroplating with tin (for tiffin boxes) or chromium (for bicycle parts, car bumpers) provides corrosion resistance and aesthetic appeal.

- Alloying to Make Stainless Steel: Iron alloyed with chromium and nickel produces stainless steel, which does not rust. Used for cutlery, utensils, surgical instruments, but expensive for large-scale use.

Chemical Reactions Summary

| Reaction Type | Equation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Metal + Oxygen | 4Na + O₂ → 2Na₂O | Sodium forms basic oxide |

| Metal Oxide + Water | Na₂O + H₂O → 2NaOH | Forms alkaline solution |

| Metal + Water | 2Na + 2H₂O → 2NaOH + H₂ | Sodium reacts vigorously |

| Metal + Acid | Zn + 2HCl → ZnCl₂ + H₂ | Produces hydrogen gas |

| Metal + Salt | Zn + CuSO₄ → ZnSO₄ + Cu | Displacement reaction |

| Non-metal + Oxygen | S + O₂ → SO₂ | Forms acidic oxide |

| Non-metal Oxide + Water | SO₂ + H₂O → H₂SO₃ | Forms acidic solution |

| Calcination | ZnCO₃ → ZnO + CO₂ | Heating without air |

| Roasting | 2ZnS + 3O₂ → 2ZnO + 2SO₂ | Heating with air |

| Reduction with Carbon | ZnO + C → Zn + CO | Moderately reactive metals |

| Electrolytic Reduction | 2Al₂O₃ → 4Al + 3O₂ | For highly reactive metals |

Practical Applications and Importance

Understanding metals and non-metals is essential for numerous industrial applications and everyday life. Metals like copper and aluminum are indispensable for electrical wiring due to their excellent conductivity. Iron and steel form the backbone of construction and manufacturing industries. Gold and silver serve both decorative and industrial purposes, from jewelry to electronics.

Non-metals are equally vital hydrogen for hydrogenation processes, nitrogen for fertilizers, carbon in multiple forms for various applications, and oxygen for respiration and combustion. The principles of chemical bonding explain the behavior of compounds, while metallurgy provides the methods to extract and purify metals economically.

Corrosion prevention techniques save billions in infrastructure maintenance costs annually. The reactivity series guides chemists and engineers in predicting reaction outcomes and selecting appropriate materials for specific environments.

For students preparing for NTSE and other competitive examinations, mastering these concepts requires understanding both theoretical principles and practical applications. The interplay between electronic configuration, chemical reactivity, bonding types, and physical properties forms a coherent framework that explains the behavior of matter around us.

This comprehensive understanding of metals and non-metals not only aids academic success but also cultivates scientific literacy essential for informed citizenship in our technologically advanced society.

Position of Metal and Non-Metals in The periodic Table:

The metals are placed on the left hand side and in the centre of the periodic table. On the other hand, the non-metals are placed on the right hand side of the periodic table. Hydrogen (H) is an exception because it is non-metal but is placed on the left hand side of the periodic table.

Metals and non-metals are separated from each other in the periodic table by a zig-zag line. The elements close to zig-zag line show properties of both the metals and the non metals. These are called metalloids. The common examples of metalloids are Boron (B), Silicon (Si), Germanium (Ge), Arsenic (As), Antimony (Sb), Tellurium (Te) and Polonium (Po).

In general, the metallic character decreases on going from left to right side in the periodic table. However, on going down the group, the metallic character increases.

METALS AND NON-METALS

Keeping these terms in mind, now we can define metal and non-metals.

Metals are defined as those elements which possess lusture, are malleable and ductile and good conductors of heat and electricity.

Or

Metals are the elements which form positive ions by losing electrons i.e. they are electropositive elements. For e.g. sodium, magnesium, potassium, aluminium, copper, silver, gold etc.

Non-metals are defined as those elements which do not possess lusture and are neither good conductors of heat and electricity nor malleable. They are not ductile but are brittle.

Or

Non-metals are the elements which form negative ions by gaining electrons i.e. they are electronegative elements.

For e.g. Carbon, Hydrogen, Oxygen, Nitrogen, Sulphur, Bromine etc.

GENERAL PROPERTIES OF METALS AND NON-METALS:

(a) Electronic Configuration of Metals:

The atoms of metals have 1 to 3 electrons in their outermost shells. For example, all the alkali metals have one electron in their outermost shells (Lithium 2, 1; Sodium 2, 8, 1; Potassium 2, 8, 8, 1 etc.).

Sodium, Magnesium and Aluminium are metals having 1, 2 and 3 electrons respectively in their valence shells. Similarly, other metals have 1 to 3 electrons in their outermost shell

PHYSICAL PROPERTIES OF METALS:

The important physical properties of metals are discussed below:

(i) Metals are solids at room temperature:

All metals (except mercury) are solid at room temperature. Mercury is liquid at room temperature.

(ii) Metals are malleable:

Metals are generally malleable. Malleability means that the metals can be beaten with a hammer into very thin sheets without breaking. Gold and Silver are among the best malleable metals. Aluminium and copper are also highly malleable metals.

(iii) Metals are ductile:

It means that metals can be drawn (stretched) into thin wires. Gold and Silver are the most ductile metals. Copper and Aluminium are also very ductile, and therefore, these can be drawn into thin wires which are used in electrical wiring.

(iv) Metals are good conductors of heat and electricity:

All metals are good conductors of heat. The conduction of heat is called thermal conductivity. Silver is the best conductor of heat. Copper and aluminium are also good conductors of heat and therefore, they are used for making household utensils. Lead is the poorest conductor of heat. Mercury metal is also a poor conductor of heat.

Metals are also good conductors of electricity. The electrical and thermal conductivities of metals are due to the presence of free electrons in them. Among all the metals, Silver is the best conductor of electricity. Copper and Aluminium are the next best conductors of electricity. Since Silver is expensive, therefore, Copper and Aluminium are commonly used for making electric wires.

(v) Metals are lustrous and can be polished:

Most of the metals have shine and they can be polished. The shining appearance of metals is also known as metallic lustre. For example, gold, silver and copper metals have metallic lustre.

(vi) Metals have high densities:

Most of the metals are heavy and have high densities. For example, the density of mercury metal is very high (13.6 g cm-3). However, there are some exceptions. Sodium, Potassium, Magnesium and Aluminium have low densities. Densities of metals are generally proportional to their atomic masses. The smaller the metal atom, the smaller is its density.

(vii) Metals are hard:

Most of the metals are hard. But all metals are not equally hard. Metals like Iron, Copper, Aluminium etc. are quite hard. They cannot be cut with a knife. Sodium and Potassium are common exceptions which are soft and can be easily cut with a knife

Sodium can be easily cut with a knife

(viii) Metals have high melting and boiling points:

Most of the metals (except Sodium and Potassium) have high melting and boiling points. Tungsten has highest melting point (3430°C) among all the metals.

(ix) Metals are rigid:

Most of the metals are rigid and they have high tensile strength.

(x) Metals are sonorous:

Most of the metals are sonorous i.e., they make sound when with an object.

Electronic Configuration of Non-Metals:

The atoms of non-metals have usually 4 to 8 electrons in their outermost shells. For example, Carbon (At. No. 6), Nitrogen (At. No. 7), Oxygen (At. No. 8), Fluorine (At. No. 9) and Neon (At. No. 10) have respectively 4,5,6,7,8 electrons in their outermost shells.

PHYSICAL PROPERTIES OF NON-METALS:

(i) Non-metals are non-malleable and non-ductile. Non-metals are brittle. The property of being brittle (breaking easily) when hammered is called brittleness.

(ii) Non-metals are bad conductors of heat and electricity. Carbon (graphite) is an exception. It is conductor of electricity and is used in making electrodes.

(iii) Non-metals are non-lustrous and dull except graphite and iodine.

(iv) Non-metals are generally soft except diamond, allotrope of carbon, which is the hardest natural substance.

(v) Non-metals have low tensile strength and they are not strong.

(vi) Non-metals possess low densities. They are light as compared to metals.

(vii) Non-metals are non-sonorous.

(viii) Non-metals may exist in solid, liquid or gaseous state at room temperature. For example sulphur and carbon are solid at room temperature, bromine is liquid and nitrogen, oxygen are gaseous non-metals.

Liquid non-metal : Bromine

(ix) All non-metals possess low melting and boiling points except graphite.

CHEMICAL PROPERTIES OF METALS:

The atoms of the metals have usually 1, 2 or 3 electrons in their outermost shells. These outermost electrons are loosely held by their nuclei. Therefore, the metal atoms can easily lose their outermost electrons to form positively charged ions. For example, sodium metal can lose outermost one electron to form positively charged ions, Na+. After losing the outermost electron, it gets stable electronic configuration of the noble gas (Ne: 2, 8). Similarly, magnesium can lose two outermost electrons to form Mg2+ ions and aluminium can lose its three outermost electrons to form AI3+ ions.

Some of the important chemical properties of metals are discussed below:

(i) Reaction with oxygen:

Metals react with oxygen to form oxides. These oxides are basic in nature. For example, sodium metal reacts with oxygen of the air and form sodium oxide.

4 Na(s) + O2(g) → 2Na2O (s) (Sodium oxide)

Sodium oxide reacts with water to form an alkali called sodium hydroxide. Therefore, sodium oxide is a basic oxide,

Na2O(s) + H2O(l) → 2NaOH (aq) (sodium hydroxide)

Due to the formation of sodium hydroxide (which is an alkali), the solution of sodium oxide in water turns red litmus blue (common property of all alkaline solutions).

Similarly, magnesium is a metal and it reacts with oxygen to form magnesium oxide. However, magnesium is less reactive than sodium and therefore, heat is required for the reaction.

2Mg(s) + O2(g)→ 2 MgO(s) (head)

Thus, when a metal combines with oxygen, it loses its valence electrons and forms positively charged metal ions. We can say that oxidation of metal takes place.

Reactivity of metals with oxygen:

All metals do not react with oxygen with equal ease. The reactivity of oxygen depends upon the nature of the metal. Some metals react with oxygen even at room temperature, some react on heating while still others react only on strong heating.

e.g.

(A) Metals like sodium, potassium and calcium react with oxygen even at room temperature to form their oxides.

(B) Metals like magnesium and zinc do not react with oxygen at room temperature. They burn in air only on strong heating to form corresponding oxides.

(C) Metals like iron and copper do not burn in air even on strong heating. However, they react with oxygen only, on prolonged heating.

(ii) Reaction with water: Metals react with water to form metal oxide or metal hydroxide and hydrogen. The reactivity of metals towards water depends upon the nature of the metals. Some metals react even with cold water, some react with water only on heating while there are some metals which do not react even with steam. For example,

(A) Sodium and potassium metals react vigorously with cold water to form sodium hydroxide and hydrogen gas is liberated.

(B) Calcium reacts with cold water to form calcium hydroxide and hydrogen gas. The reaction is less violent.

(C) Magnesium reacts very slowly with cold water but reacts rapidly with hot boiling water forming magnesium oxide and hydrogen.

(D) Metals like zinc and aluminium react only with steam to form zinc oxide and hydrogen.

(E) Iron metal does not react with water under ordinary conditions. The reaction occurs only when steam is passed over red hot iron and the products are iron (II,III) oxide and hydrogen.

(F) Metals like copper, silver and gold do not react with water even under strong conditions. The order of reactivities of different metals with water is:

Na > Mg > Zn > Fe > Cu

Reactivity with water decreases

(iii) Reaction with dilute acids:

Many metals react with dilute acids and liberate hydrogen gas. Only less reactive metals such as copper, silver, gold etc. do not liberate hydrogen from dilute acids. The reactions of metals with dilute hydrochloric acid (HCI) and dilute Sulphuric acid (H2S04) are similar. With dil. HCI, they give metal chlorides and hydrogen whereas with dil. H2S04, they give metal sulphates and hydrogen.

The reactivity of different metals is different with the same acid. For example:

(A) Sodium, magnesium and calcium react violently with dilute hydrochloric acid (HCI) or dilute Sulphuric acid (H2SO4) liberating hydrogen gas and corresponding metal salt.

(B) Iron reacts slowly with dilute HCl or dil. H2SO4 and therefore, it is less reactive than zinc and aluminium.

(C) Copper does not react with dil. HCl or dil. H2SO4

Therefore copper is even less reactive than iron.

The order of reactivity of different metals with dilute acid.

Na > Mg > Al > Zn > Fe > Cu

Reactivity with dil acids decreases from sodium to copper.

(iv) Reactions of metals with salt solutions:

When a more reactive metal is placed in reactive metal from its salt solution of less reactive metal, then the more reactive metal displaces the less reactive metal from its salt solution. For example, we will take a solution of copper sulphate (blue coloured solution) and put a strip of zinc metal in the solution. It is observed that the blue colour of copper sulphate fades gradually and copper metal is deposited on the zinc strip. This means that the following reaction occurs:

Here, zinc displaces copper from its salt solution.

However, if we take zinc sulphate solution and put a strip of copper metal in this solution, no reaction occurs.

This means that copper cannot displace zinc metal from its solution. Thus, we can conclude that zinc is more reactive than copper. However, if we put gold or platinum strip in the copper sulphate solution, then copper is not displaced by gold or platinum. Thus, gold and platinum are less reactive than copper.

REACTIVITY SERIES OF METALS:

(a) Introduction:

We have learnt that some metals are chemically very reactive while others are less reactive or do not react at all.

On the basis of reactivity of different metals with oxygen, water and acids as well as displacement reactions, the metals have been arranged in the decreasing order of their reactivities.

The arrangement of metals in order of decreasing, reactivities is called reactivity series or activity series of metals.

The activity series of some common metals is given in Table. In this table, the most reactive metal is placed at the top whereas the least reactive metal is placed at the bottom. As we go down the series the chemical reactivity of metals decreases.

REACTIVITY SERIES OF METALS

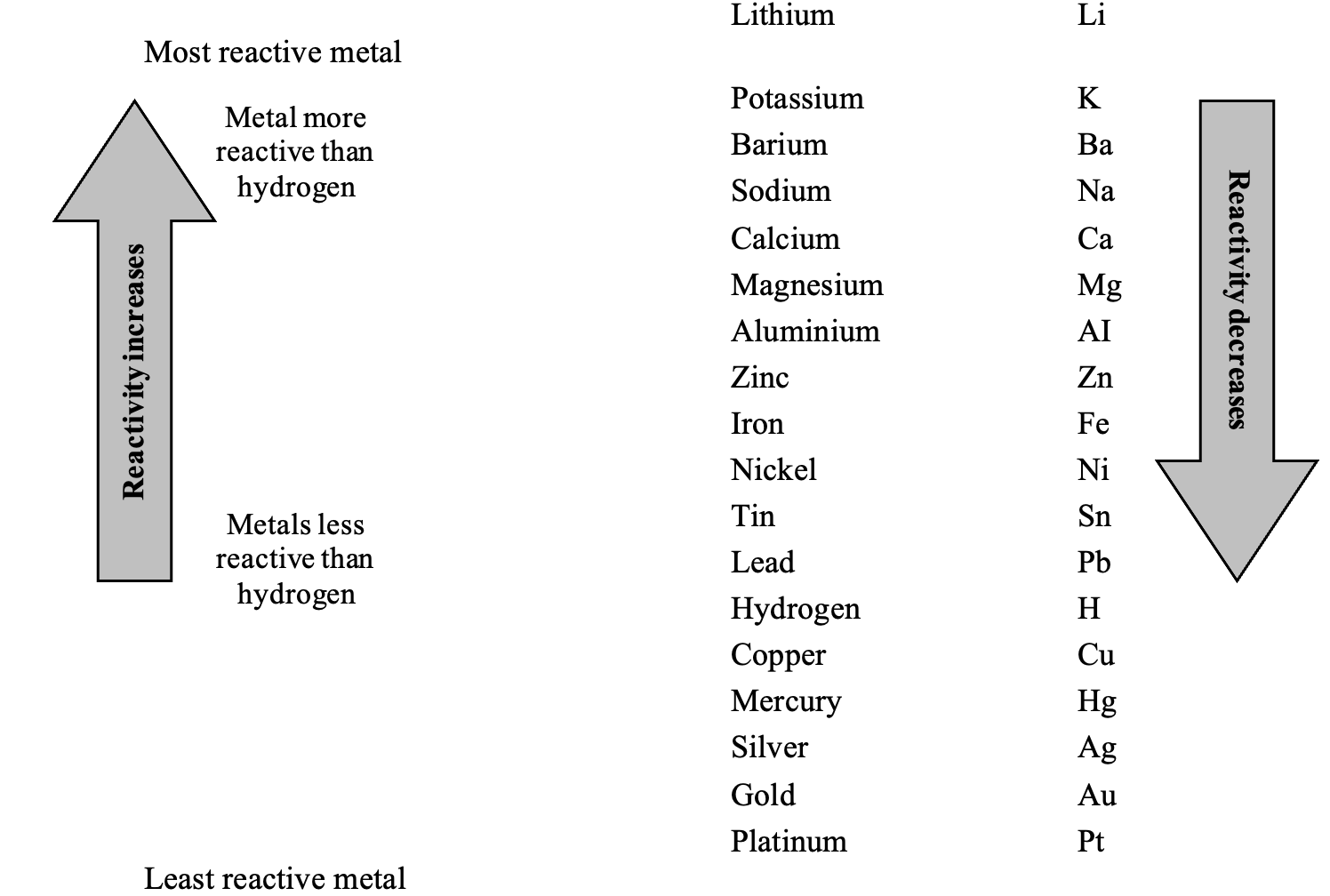

(b) Reasons for Different Reactivities:

In the activity series of metals, the basis of reactivity is the tendency of metals to lose electrons. If a metal can lose electrons easily to form positive ions, It will react readily with other substances. Therefore, it will be a reactive metal. On the other hand, if a metal loses electrons less rapidly to form a positive ion, it will react slowly with the other substances. Therefore, such a metal will be less reactive. For example, alkali metals such as sodium and potassium lose electrons very readily to form alkali- metal ions; therefore, they are very reactive.

(c) Displacement of Hydrogen from Acids by Metals:

All metals above hydrogen in the reactivity series (i.e. more active than hydrogen) like zinc, magnesium, nickel can liberate hydrogen from acids like HCI and H2SO4. These metals have greater tendency to lose electrons than hydrogen. Therefore, the H+ ions in the acids will accept electrons and give hydrogen gas as:

The metals which are below hydrogen in the reactivity series (i.e. less reactive than hydrogen) like copper, silver, gold cannot liberate hydrogen form acids like HCI, H2SO4 etc. These metals have lesser tendency to lose electrons than hydrogen. Therefore, they cannot lose electrons to H+ ions.

(d) Reactivity Series and Displacement Reactions:

The reactivity series can also explain displacement reactions. In general, a more reactive metal (placed higher in the activity series) can displace the less reactive metal from its solution. For example, zinc, displaces copper from its solution.

Zn (s) + CuSO4 (aq) ZnSO4 (aq) + Cu(s)

(e) Uses of Activity Series:

The activity series is very useful and it gives the following informations:

(i) The metal which is higher in the activity series is more reactive than the other. Lithium is the most reactive and platinum is the least reactive.

(ii) The metals which have been placed above hydrogen are more reactive than hydrogen and these can displace hydrogen from its compounds like water and acids to liberate hydrogen gas.

(iii) The metals which are placed below hydrogen are less reactive than hydrogen and these cannot displace hydrogen from its compounds like water and acids.

(iv) A more reactive metal (placed higher in the activity series) can displace the less reactive metal from its solution.

(v) Metals at the top of the series are very reactive and therefore, they do not occur free in nature. The metals at the bottom of the series are least reactive and therefore, they normally occur free in nature. For example, gold, present in the reactivity series is found in Free State in nature.

CHEMICAL PROPERTIES OF NON-METALS:

The non-metals are electronegative elements, i.e. they form negative ions by gaining electrons. In other words, non-metals have tendency to gain electrons and hence undergo reduction.

Reaction of non-metals with Oxygen:

Non-metals react with oxygen to form oxides. These oxides are covalent in nature and are generally gaseous. Most of these oxides when dissolved in water give acidic solution. These solutions turn blue litmus red. For example, sulphur when burnt in the presence of Oxygen forms Sulphur dioxide.

Reaction of non-metals with water:

Non-metals do not react with water or steam to evolve hydrogen gas because they do not lose electrons to reduce hydrogen ions (H+) into hydrogen gas.

Reaction of non-metals with acids:

Non-metals do not displace hydrogen from acids. For the liberation of hydrogen the non-metals should be able to reduce H+ ions to H2 gas by supplying electrons. However, non-metals are electronegative elements and hence have more tendency to accept electrons rather than donating. Hence, non-metals do not produce hydrogen gas on reaction with acids.

Reaction of non-metals with salt Sol:

A more reactive non-metal displaces a less reactive non-metal from its salt solution. For example:

When chlorine is passed through a solution of sodium bromide, then sodium chloride and bromine are formed.

2NaBr + Cl₂ ⟶ 2NaCl + Br₂

Sodium Bromide Chlorine Sodium Chloride Bromine

Reaction of non-metals with chlorine:

Non-metals react with chlorine to form chlorides. These chlorides are covalent in nature and are generally gaseous or liquids.

(a) Hydrogen reacts with chlorine to form covalent chloride called hydrogen chloride.

H₂ + Cl₂ ⟶ 2HCl

Hydrogen Chlorine Hydrogen chloride

(b) Phosphorus reacts with chlorine to form covalent chloride called phosphorus trichloride and phosphorus pentachloride.

P₄ + 6Cl₂ ⟶ 4PCl₃

Phosphorus Chlorine Phosphorus trichloride

P₄ + 10Cl₂ ⟶ 4PCl₅

Phosphorus Chlorine Phosphorus pentachloride

Reaction of non-metals with hydrogen:

Non-metals on reaction with hydrogen form hydrides which are covalent in nature. Most of these hydrides are gases or liquids. Some examples are:

(a) 2H₂ + O₂ → 2H₂O Hydrogen Oxygen Water

(b) N₂ + 3H₂ → 2NH₃ Nitrogen Hydrogen Ammonia

(c) H₂ + S → H₂S Hydrogen Sulphur Hydrogen sulphide

Oxidising Nature:

Since non-metals have great tendency to accept electrons, therefore, many non-metals act as good oxidizing agents. For example, fluorine is the strongest oxidizing agent among all the non-metals.

(a) Zn + S → Zn²⁺ S²⁻ Zinc + Sulphur → Zinc sulphide

(b) 2Na + Cl₂ → 2Na⁺ Cl⁻ Sodium + Chlorine → Sodium chloride

Difference Between MEtals and Non-metals:

| Properties | Metals | Non-metals |

| Physical Properties | ||

| 1. State | Metals are solids at ordinary temperature except mercury, which is a liquid. | Non-metals exist in all the three states, that is, solid, liquid and gas. |

| 2. Lustre | They possess lustre or shine. | They possess no luster except iodine and graphite. |

| 3. Malleability and Ductility | Metals are generally malleable and ductile. | Non-metals are neither malleable nor ductile. |

| 4. Hardness | Metals are generally hard. Alkali metals are exception. | Non-metals possess varying hardness. Diamond is an exception. It is the hardest substance known to occur in nature. |

| 5. Density | They have high densities. | They generally possess low densities. |

| 6. Conductivity | Metals are good conductors of heat and electricity. | Non-metals are poor conductors of heat are electricity. The only exception is graphite which is a good conductor of electricity. |

| 7. Melting and boiling point | They usually have high melting and boiling point. | Their melting and boiling point are usually low. The exceptions are boron, carbon and silicon. |

Chemical Properties

1. Action with mineral acids

Metals: Metals generally react with dilute mineral acids to liberate hydrogen gas.

Non-metals: Non-metals do not displace hydrogen on reaction with dilute minerals acids.

2. Nature of oxides

Metals: They form basic oxides. For example, Na₂O, MgO, etc. These oxides are ionic in nature.

Non-metals: Non-metals form acidic or neutral oxides. For example, SO₂, CO₂, P₂O₅, are acidic whereas CO, N₂O, are neutral. These oxides are covalent in nature.

3. Combination with hydrogen

Metals: Metals generally do not combine with hydrogen. However Li, Na, Ca, etc. form unstable hydrides. For example, LiH, NaH, CaH₂ etc. These hydrides are ionic in character.

Non-metals: Non-metals combine with hydrogen to form stable hydrides. For example, HCl, H₂S, CH₄, NH₃, PH₃, etc. These hydrides are covalent.

4. Combination with halogens

Metals: They combine with halogens to form well defined and stable crystalline solids. For example, NaCl, KBr, etc.

Non-metals: Non-metals form halides which are unstable and undergo hydrolysis readily. For example, PCl₃, PCl₅, etc.

5. Electrochemical behaviour

Metals: Metals are electropositive in character. They form cations in solution and are deposited on the cathode when electricity is passed through their solution.

Non-metals: Non-metals are electronegative in character. They form anions in solution and are liberated at the anode when their salt solutions are subjected to electrolysis. Hydrogen in an exception. It usually forms positive ions and is liberated at cathode.

6. Oxidising or reducing behaviour

Metals: Metals behave as reducing agents. This is because of their tendency to lose electrons. Na → Na⁺ + e⁻

Non-metals: Non-metals generally behave as oxidising agents since they have the tendency to gain electrons. ½Cl₂ + e⁻ → Cl⁻

USES OF METALS:

Metals are used for a large number of purposes. Some of the uses of metals are given below:

(i) Copper and aluminium metals are used to make wires to carry electric current. This is because copper and aluminium have very low electrical resistance and hence very good conductors of electricity.

(ii) Iron, copper and aluminium metals are used to make house-hold utensils and factory equipments.

(iii) Iron is used as a catalyst in the preparation of ammonia gas by Haber’s process.

(iv) Zinc is used for galvanizing iron to protect it from rusting.

(v) Chromium and nickel metals are used for electroplating and in the manufacture of stainless steel.

(vi) The aluminium foils are used in packaging of medicines, cigarettes and food materials.

(vii) Silver and gold metals are used to make jewellery. The thin foils made of silver and gold are used to decorate sweets.

(viii) The liquid metal ‘mercury’ is used in thermometers.

(ix) Sodium, titanium and zirconium metals are used in atomic energy (nuclear energy) and space science projects.

(x) Zirconium metal is used in making bullet-proof alloy steels.

USES OF NON-METALS:

The important uses of non-metals are as follows:

(i) Hydrogen is used in the hydrogenation of vegetable oils to make vegetable ghee (or vanaspati ghee).

(ii) Hydrogen is used in the manufacture of ammonia (whose compounds are used as fertilisers).

(iii) Liquid hydrogen is used as a rocket fuel.

(iv) Carbon (in the form of graphite) is used for making the electrodes of electrolytic cells and dry cells.

(v) Nitrogen is used in the manufacture of ammonia, nitric acid and fertilisers.

(vi) Due to its inertness, nitrogen is used to preserve food materials.

(vii) Compounds of nitrogen like Tri Nitro Toluene (TNT) and nitroglycerine are used as explosives.

(viii) Sulphur is used for manufacturing sulphuric acid.

(ix) Sulphur is used as a fungicide and in making gun powder.

(x) Sulphur is used to the vulcanisation of rubber.

WHY DO METALS AND NON-METALS REACT?

When metals react with non-metals, they form ionic compounds (which contain ionic bonds). On the other hand, when non-metals react with other non-metals, they form covalent compounds (which contain covalent bonds).

The force which holds a number of atoms together within the compound or the molecule is called a chemical bond.

To understand the formation of chemical bond ‘between the atoms of metals and non-metals’ or ‘between the atoms of two non-metals’, it is necessary to know the reason for the unreactive nature (or inertness) of noble gases.

There are some elements in group 18 of the periodic table which do not combine with other elements. These elements are : Helium, Neon, Argon, Krypton, Xenon and Radon. They are known as noble gases or inert gases because they do not react with other elements to form compounds. In other words, inert gases do not form chemical bonds.

That is why they are called noble gases or inert gases and exist as monatomic gases, i.e., as He, Ne, Ar, Kr, Xe and Rn.

Electronic Configurations of Noble Gases

| S.No. | Element | Symbol | Atomic No. | Electronic configuration |

| KLMNOP | ||||

| 1. | Helium | He | 2 | 2 |

| 2. | Neon | Ne | 10 | 2, 8 |

| 3. | Argon | Ar | 18 | 2, 8, 8 |

| 4. | Krypton | Kr | 36 | 2, 8, 18, 8 |

| 5. | Xenon | Xe | 54 | 2, 8, 18, 18, 8 |

| 6. | Radon | Rn | 86 | 2, 8, 18, 32, 18, 8 |

When we look at their electronic configuration, as given in the above table, we observe that except in case of helium, where there are two electrons present in the outermost shell, all other noble gases have eight electrons present in the outermost shell. The presence of two electrons in the outermost shell is called a duplet whereas the presence of eight electrons in the outermost shell is called an octet. Thus, the cause of stability of noble gases is due to presence of duplet of electrons in case of helium and presence of octet of electrons in case of other noble gases.

Electronic Configurations of some common Metals and Non-metals

|

Name of the |

Symbol |

Atomic No. |

Electronic configuration |

|||

|

K |

L |

M |

N |

|||

|

Lithium |

Li |

3 |

2 |

1 |

||

|

Sodium |

Na |

11 |

2 |

8 |

1 |

|

|

Magnesium |

Mg |

12 |

2 |

8 |

2 |

|

|

Aluminium |

Al |

13 |

2 |

8 |

3 |

|

|

Potassium |

K |

19 |

2 |

8 |

8 |

1 |

|

Calcium |

Ca |

20 |

2 |

8 |

8 |

2 |

|

Name of the |

Symbol |

Atomic No. |

Electronic configuration |

|||

|

K |

L |

M |

N |

|||

|

Nitrogen |

N |

7 |

2 |

5 |

||

|

Oxygen |

O |

8 |

2 |

6 |

||

|

Fluorine |

F |

9 |

2 |

7 |

||

|

Phosphorus |

P |

15 |

2 |

8 |

5 |

|

|

Sulphur |

S |

16 |

2 |

8 |

6 |

|

|

Chlorine |

Cl |

17 |

2 |

8 |

7 |

|

When we look at the electronic configuration of few metals and non-metals, as given in the above table, we observe that their outermost shell has less than eight electrons. So, all atoms tend to complete their octets (i.e., outermost shell with eight electrons) or duplet (i.e., outermost shell with two electrons) if K-shell is the outermost shell to acquire stability. Thus, the cause of chemical combination is the tendency of the atoms to complete their octet (i.e., outermost shell with eight electrons) or duplet (i.e., outermost shell with two electrons in case of elements having only K-shell) so that they acquire the stable nearest noble gas configuration.

Modes of Chemical combination:

As explained above, when atoms combined, they complete their octets (or duplets) by any one of the following methods:

(i) By losing one or more electrons (to another atom).

(ii) By gaining one or more electrons (from another atom).

(iii) By sharing one or more electrons (with another atom).

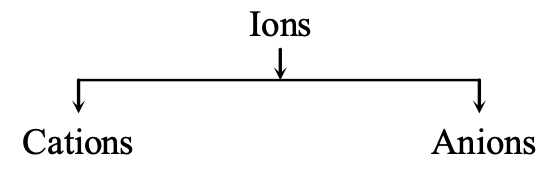

Ions:

An ion is an electrically charged atom (or group of atoms). Examples of the ions are : sodium ion, Na+, magnesium ion, Mg2+, chloride ion, Cl–, and oxide ion, O2–. An ion is formed by the loss or gain of electrons by an atom.

A positively charged ion is known as cation.

Sodium ion, Na⁺, and magnesium ion, Mg²⁺, are cations because they are positively charged ions. A cation is formed by the loss of one or more electrons by an atom. For example, sodium atom loses one electron to form a sodium ion, Na⁺, which is a cation.

Na - e⁻ ⟶ Na⁺

Sodium atom | Electron | Sodium ion Electronic K L M | | K L Configuration: 2, 8, 1 | | 2, 8

(unstable electron arrangement) | (Stable, neon gas electron arrangement)

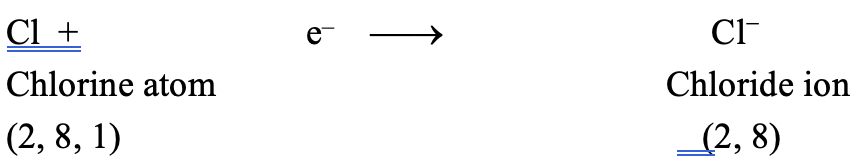

A negatively charged ion is known as anion.

Chloride ion, Cl⁻, and oxide ion, O²⁻, are anion because they are negatively charged ion. An anion is formed by the gain of one or more electrons by an atom. For example, a chlorine atom gains (accepts) one electron to form a chlorine ion, Cl⁻, which is an anion.

Cl + e⁻ ⟶ Cl⁻

Chlorine atom | Electron | Chloride ion Electronic K L M | | K L M Configuration: 2, 8, 7 | | 2, 8, 8

(unstable electron arrangement) | (stable argon gas electron arrangement)

ELECTRONIC DOT REPRESENTATION (LEWIS SYMBOLS):

In the formation of a chemical bond between two atoms, only the electrons of the outermost shell are involved (as the inner shell electrons are well protected). These electrons present in the outermost shell are called valence electrons.

G.N. Lewis introduced a simple method of representing the valence electrons by dots or small crosses around the symbol of the atom. These symbols are known as electron dot symbols or Lewis symbols. These symbols ignore the inner shell electrons.

Electron dot (Lewis symbols) of some common elements

|

Element |

Symbol |

Atomic No. |

Electronic configuration |

Valence electrons |

Lewis symbol |

|||

|

K |

L |

M |

N |

|||||

|

Hydrogen |

H |

1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

|

Helium |

He |

2 |

2 |

2 |

||||

|

Lithium |

Li |

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|||

|

Beryllium |

Be |

4 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

|||

|

Boron |

B |

5 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

|||

|

Carbon |

C |

6 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

` |

||

|

Nitrogen |

N |

7 |

2 |

5 |

5 |

|||

|

Oxygen |

O |

8 |

2 |

6 |

6 |

|||

|

Fluorine |

F |

9 |

2 |

7 |

7 |

|||

|

Neon |

Ne |

10 |

2 |

8 |

8 |

|||

|

Sodium |

Na |

11 |

2 |

8 |

1 |

1 |

||

|

Magnesium |

Mg |

12 |

2 |

8 |

2 |

2 |

||

|

Aluminium |

Al |

13 |

2 |

8 |

3 |

3 |

||

|

Chlorine |

Cl |

17 |

2 |

8 |

7 |

7 |

||

|

Potassium |

K |

19 |

2 |

8 |

8 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Calcium |

Ca |

20 |

2 |

8 |

8 |

2 |

2 |

|

Types of Chemical Bonds:

There are two types of chemical bonds:

(i) Ionic bond,

(ii) Covalent bond.

Ionic bonds are formed by the transfer of electrons from one atom to another whereas covalent bonds are formed by the sharing of electrons between two atoms. Ionic bond is also called electrovalent bond.

Concept of Ionic Bond:

Except the elements of group 18 of the periodic table all the elements of the remaining group, at normal temperature and pressure, are not stable in independent state. These elements form stable compounds either by combining with the other atoms or with their own atoms. When in gross electronic configuration of the elements there are 8 electrons present then these elements do not take part in the chemical reaction because atoms containing 8 electrons in their outermost shell are associated with extra stability and less energy. Atoms with other electronic configuration, which do not contain eight electrons in their outermost shell, are unstable and to achieve the stability they chemically combine in such a manner that they achieve eight electrons in their outermost shell.

Two or more than two types of atoms mutually combine with each other to achieve stable configuration of eight valence electrons. Attempt to achieve eight electrons in the outermost orbit of an element is the reason behind its chemical reactivity or chemical bonding.

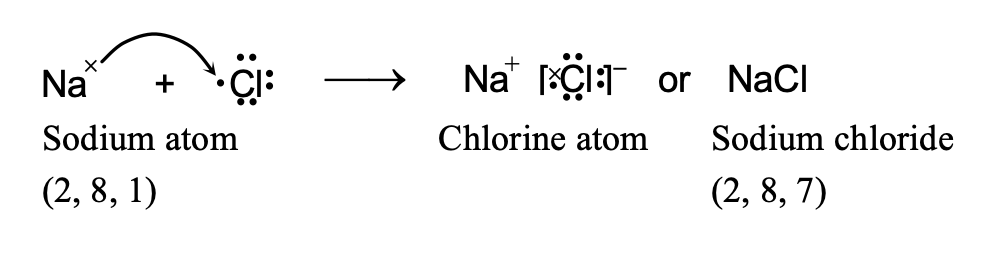

(i) Formation of Sodium Chloride.

Atomic number of sodium (Na) = 11

\ Its electronic configuration is 2, 8, 1.

It has only one electron in the valence shell. It loses this electron to acquire the stable electronic configuration 2, 8 (similar to that of neon) and forms sodium ion (Na+).

Atomic number of chlorine (Cl) = 17

Its electronic configuration is 2, 8, 7.

It has seven electrons in the valence shell. It gains one electron to acquire the stable electronic configuration 2, 8, 8 (similar to that of argon) and form chloride ion (Cl–)

Thus, when a sodium atom and a chlorine atom approach each other, an electron is transferred from sodium atom to chlorine atom. In other words, sodium loses one electron to form Na+ ion and chlorine gains that electron to form Cl– ion. As a result, both acquire the stable nearest noble gas configuration. These oppositely charged ions are then held together by electrostatic forces of attraction forming the compound Na+Cl– or simply written as NaCl. The transfer of electron may be represented in one step as follows:

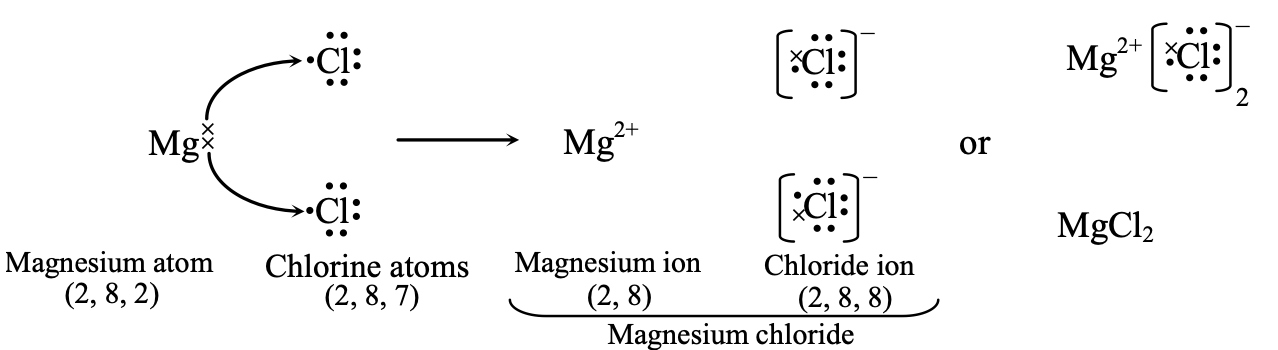

(ii) Formation of Magnesium chloride.

Atomic number of magnesium (Mg) = 12

∴ Its electronic configuration = 2, 8, 2

It loses two electrons from the valence shell to acquire the nearest noble gas configuration of neon (2, 8) and form Mg2+ ion.

Atomic number of chlorine (Cl) = 17

It electronic configuration = 2, 8, 7

It needs to gain only one electron in the valence shell to acquire the nearest noble gas configuration of argon (2, 8, 8) and form chloride ion (Cl–). Now, as magnesium atom has to lose two electrons and a chorine atom can gain only one electron, therefore, two chlorine atoms will be required to accept the two electrons, one by each chlorine atom.

Thus, the transference of two electrons from one Mg atom to two Cl atoms may be represented as follows:

Thus, here one magnesium atom combines with two chlorine atoms. Therefore, the formula of magnesium chloride is MG2+ Cl2- or MgCl2 . Here, again the oppositely charged ions are held together by electrostatic forces of attraction.

(iii) Formation of Magnesium Oxide.

Atomic number of magnesium (Mg) = 12

∴ Its electronic configuration = 2, 8, 2

It loses two electrons from the valence shell to acquire the stable configuration of neon

(2, 8) and form Mg2+ ion.

Atomic number of oxygen (O) = 8

∴ Its electronic configuration = 2, 6

It gains two electrons in the valence shell to acquire the stable configuration of neon again (2, 8) and form oxide ion (O2–).

Thus, in the formation of magnesium oxide, two electrons are transferred from magnesium atom to oxygen atom as represented below :

Covalent bond:

The chemical bond formed by the sharing of electrons between two atoms is known as a covalent bond. The sharing of electrons takes place in such a way that each atom in the resulting molecule gets the stable electron arrangement of an inert gas.

Whenever a non-metal combines with another non-metal, sharing of electrons takes place between their atoms and a covalent bond is formed. A covalent bond can also be formed between two atoms of the same non-metal.

Covalent bonds are of three types :

(i) Single covalent bond

(ii) Double covalent bond

(iii) Triple covalent bond

(i) Single Bond

Single bond is formed by the sharing of one pair of electrons between two atoms. A single covalent bond is formed by the sharing of two electrons between the atoms, each atom contributing one electron for sharing.

Ex. A hydrogen molecule H2, contains a single covalent bond and it is written as H : H, the two dots drawn between the hydrogen atoms represent a pair of shared electrons which constitutes the single bond. A single covalent bond is denoted by putting one short line (-) between the two atoms and is written as H–H.

(a) Formation of a Hydrogen Molecule, H2 : A hydrogen atom is very reactive and cannot exist free because it does not have the stable, inert gas electron arrangement. So, hydrogen gas does not consist of single atoms, it consists of more stable H2 molecules.

The atomic number of hydrogen is 1, so its electronic configuration is K 1. Hydrogen atom has only one electron in the outermost shell (which is K shell), and this is not a stable arrangement of electrons. A stable arrangement is to have two electrons in the K shell because then the helium gas electron structure will be achieved. Thus, a hydrogen atom needs one more electron to become stable. It gets this electron by sharing with another hydrogen atom. So, two hydrogen atoms share one electron each to form a hydrogen molecule.

The formation of a hydrogen molecule from two hydrogen atoms can be shown by the following diagram:

(b) Formation of a Water Molecule, H2O : Water is a covalent compound consisting of hydrogen and oxygen. It contains single covalent bonds. The formation of a water molecule from hydrogen and oxygen can be explained as follows :

The hydrogen atom has only one electron in its outermost K shell, so it needs one more electron to achieve the stable, two electrons arrangement of the inert gas helium. The oxygen atom has six electrons in its outermost shell, and it needs two more electrons to complete the stable, eight electron arrangement of inert gas neon. So, one atom of oxygen shares its two electrons with two hydrogen atoms to form a water molecule.

(ii) Double Bond

Double bond is formed by the sharing of two pairs of electrons between two atoms. A double covalent bond is formed by the sharing of four electrons between two atoms, each atom contributing two electrons for sharing.

It is represented by putting two short lines (=) between the two atoms. For example, oxygen molecule, O2, contains a double bond between two atoms and it can be written as O=O.

(a) Formation of Oxygen Molecule, O2 : Oxygen atom is very reactive and cannot exist free because it does not have the stable, inert gas electron arrangement in its valence shell. The atomic number of oxygen is 8, so its electronic configuration is 2, 6. Thus, an oxygen atom has six electrons in its outermost shell. It requires two more electrons to achieve the stable, eight electron inert gas configuration. The oxygen atom gets these electrons by sharing its two electrons with the two electrons of another oxygen atom. So, two oxygen atoms share two electrons each and form a stable oxygen molecule.

(b)Formation of Carbon Dioxide Molecule, CO2 : Carbon dioxide is a covalent compound made up of carbon and oxygen elements and its contains covalent bonds in it.

Carbon atom has four valence electrons, so it needs four more electrons to achieve the eight-electron inert gas configuration and become stable. Oxygen atom has 6 valence electrons and it needs two more electrons to achieve the eight-electron configuration and become stable. So, one carbon atoms shares its four electrons with two oxygen atoms and forms a carbon dioxide molecule:

There are two double bonds in a carbon dioxide molecule.

(iii) Triple Bond

A triple bond is formed by the sharing of three pairs of electrons between two atoms. A triple bond is formed by the sharing of six electrons between two atoms, each atom contributing three electrons for sharing. A triple bond is actually a combination of three single bonds, so it is represented by putting three short lines (º) between the two atoms. Nitrogen molecule, N2, contains a triple bond, so it can be written as N º N.

(a) Formation of a Nitrogen Molecule, N2 : A nitrogen atom is very reactive and cannot exist free because it does not have the stable electron arrangement of an inert gas. The atomic number of nitrogen is 7, so its electronic configuration is 2, 5. This means that a nitrogen atom has five electrons in its outermost shell. Since a nitrogen atom has five electrons in its outermost shell, it needs three more electrons to achieve the eight electron structure of an inert gas and become stable. So, two nitrogen atoms combine together by sharing three electrons each to form a molecule of nitrogen gas.

Properties of Ionic Compounds:

(i) Ionic Compounds consists of ions: All ionic compounds consist of positively and negatively charged ions and molecules. For example, sodium chloride consists of Na+ and CI- ions, magnesium fluoride consists of Mg2+ and F- ions and so on.

(ii) Physical nature: Ionic compounds are solid and relatively hard due to strong electrostatic force of attraction between the ions of ionic compound.

Laboratory Test: Collect samples of sodium chloride, potassium chloride, barium chloride or any other salt from the laboratory. We see that they are all solids and brittle, i.e., they break into pieces if some force (e.g., hammer) is applied on them.

(iii) Crystal structure: X-ray studies have shown that ionic compounds do not exist as simple single molecules as Na+CI-. This is due to the fact that the forces of attraction are not restricted to single unit such as Na+ and CI- but due to uniform electric field around an ion, each ion is attracted to a large number of other ions. For example, one Na+ ion will not attract only one CI- ion but it can attract as many negative charges as it can. Similarly, the CI- ion will attract several Na+ ions. As a result, there is a regular arrangement of these ions in three dimensions. Such a regular arrangements is called crystal lattice.

(iv) Melting point and boiling point: Strong electrostatic force of attraction is present between ions of opposite charges. To break the crystal lattice more energy is required so their melting points and boiling points are high.

Laboratory Test: Take any of the above salts in a dry pyrex or corning glass test tube (which can withstand high temperature). Hold in a test tube holder and heat it in the Bunsen burner. We will observe that it is difficult to melt it.

(v) Solubility: Ionic compounds are generally soluble in polar solvents like water and insoluble in non - polar solvents like carbon tetrachloride, benzene, ether, alcohol etc.

Laboratory Test: Shake the samples of the salts taken above one by one with water, alcohol, petrol and kerosene oil taken in four test tubes separately. We find that the salts are soluble in water but insoluble in other solvents.

(vi) Brittle nature: Ionic compounds on applying external force or pressure are broken into small pieces, such substances are known as brittle and this property is known as brittleness. When external force is applied on the ionic compound, layers of ions slide over one another and particles of the same charge come near to each other as a result due to the strong repulsion force, crystals of compounds are broker.

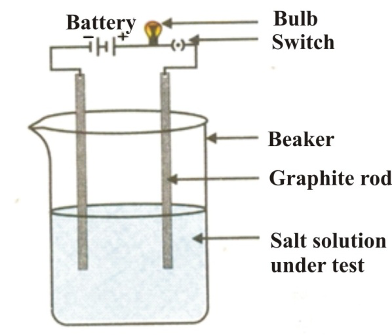

(v) Electrical conductivity: Electrical conductivity in any substance is due to the movement of free electrons or ions. In metals electrical conductivity is due to the free movement of valence electrons. An ionic compound exhibits electrical conductivity due to the movement of ions either in the fused state or in the soluble state in the polar solvent. But in the solid state due to strong electrostatic force of attraction free ions are absent so they are insulator in the solid state.

Laboratory Test: Take water in a beaker and dissolve any one of the salts (NaCl or KI) into it. Set up the electrical circuit as shown in figure below :

On switching on the current, the bulb is found to glow. This shows that the salt solution conducts electricity.

Properties of covalent compounds:

(i) Covalent compounds are usually liquids or gases. Only some of them are solids. For example, alcohol, ether, benzene, carbon disulphide, carbon tetrachloride and bromine are liquids; methane, ethane, ethene, ethyne, and chlorine are gases. Glucose, cane sugar, urea, naphthalene and iodine are, however, solid covalent compounds. The covalent compounds are usually liquids or gases due to the weak force of attraction between their molecules.

(ii) Covalent compounds have usually low melting points and low boiling points. For example, naphthalene has a low melting point of 80°C.

(iii) Covalent compounds are usually insoluble in water but they are soluble in organic solvents. For example, naphthalene is insoluble in water but dissolves in organic solvents like ether.

(iv) Covalent compounds do not conduct electricity. This means that covalent compounds are non-electrolytes. Covalent compounds do not conduct electricity because they do not contain ions.

Difference between ionic and covalent compounds

| Ionic Compounds | Covalent Compounds |

| 1. Ionic compounds are usually crystalline solids. | 1. Covalent compounds are usually liquids or gases. Only some of them are solids. |

| 2. Ionic compounds have high melting points and boiling points. That is, ionic compounds are non-volatile. | 2. Covalent compounds have usually low melting points and boiling points. That is, covalent compounds are usually volatile. |

| 3. Ionic compounds conduct electricity when dissolved in water or melted. | 3. Covalent compounds do not conduct electricity. |

| 4. Ionic compounds are usually soluble in water. | 4. Covalent compounds are usually insoluble in water (except, glucose, sugar, urea, etc.). |

| 5. Ionic compounds are insoluble in organic solvents (like alcohol, ether, acetone, etc.). | 5. Covalent compounds are soluble in organic solvents. |

OCCURRENCE OF METALS:

All metals are present in the earth's crust either in the Free State or in the form of their compounds. Aluminium is the most abundant metal in the earth's crust. The second most abundant metal is iron and third one is calcium.

Native and Combined States of Metals:

Metals occur in the crust of earth in the following two states -

(i) Native state or Free State: A metal is said to occur in a free or a native state when it is found in the crust of the earth in the elementary or uncombined form.

The metals which are very unreactive (lying at the bottom of activity series) are found in the Free State. These have no tendency to react with oxygen and are not attacked by moisture, carbon dioxide of air or other non-metals. Silver, copper, gold and platinum are some examples of such metals.

(ii) Combined state: A metal is said to occur in a combined state if it is found in nature in the form of its compounds. E.g. Sodium, magnesium etc. Copper and silver are metals which occur in the Free State as well as in the combined state.

MINERALS AND ORES:

In the combined state, the metals are found in the crust of earth as oxides, carbonates, sulphides, silicates, phosphates etc.

The inorganic elements or compounds which occur naturally in the earth’s crust are known as minerals. At some places, the minerals contain a very high percentage of a particular metal and the metal can be profitably extracted from it. Those minerals from which a metal can be profitably extracted are called ores.

When an ore is mined from earth, it is always found to be contaminated with sand and rocky materials. These impurities of sand and rocky materials present in the ore are known as gangue.

Types of ores:

The most common ores of metals are oxides, sulphides, carbonates, sulphates, halides, etc. In general, very unreactive metals (such as Gold, Silver, Platinum etc.) occur in elemental form or free state.

(i) Metals which are only slightly reactive occur as sulphides (e.g., CuS, PbS etc.).

(ii) Reactive metals occur as oxides (e.g., MnO2, AI2O3 etc.).

(iii) Most reactive metals occur as salts as carbonates, sulphates, halides etc. (e.g., Ca, Mg, K etc.).

Some common ores are listed in the table:

|

Nature of ore |

Metal |

Name of the ore |

Composition |

|

Oxide ores |

Aluminium |

Bauxite |

Al2O3.2H2O |

|

Copper |

Cuprite |

Cu2O |

|

|

Iron |

Magnetite |

Fe3O4 |

|

|

Haematite |

Fe2O3 |

||

|

Sulphide ores |

Copper |

Copper pyrites |

CuFeS2 |

|

Copper glance |

Cu2S |

||

|

Zinc |

Zinc blende |

ZnS |

|

|

Lead |

Galena |

PbS |

|

|

Mercury |

Cinnabar |

HgS |

|

|

Carbonate ores |

Calcium |

Limestone |

CaCO3 |

|

Zinc |

Calamine |

ZnCO3 |

|

|

Halide ores |

Sodium |

Rock salt |

NaCI |

|

Magnesium |

Carnallite |

KCI.MgCI2.6H2O |

|

|

Calcium |

Fluorspar |

CaF2 |

|

|

Silver |

Horn silver |

AgCI |

|

|

Sulphate Ores |

Calcium |

Gypsum |

CaSO4.2H2O |

|

Magnesium |

Epsom salt |

MgSO4.7H2O |

|

|

Barium |

Barytes |

BaSO4 |

|

|

Lead |

Anglesite |

PbSO4 |

Metallurgy

The process of extracting pure metals from their ores and then refining them for use is called metallurgy.

In other words, the process of metallurgy involves extraction of metals from their ores and then refining them for use. The ores generally contain unwanted impurities such as sand, stone, earthy particles, limestone, mica, etc., these are called gangue or matrix. The process of metallurgy depends upon the nature of the ore, nature of the metal and the types of impurities present. Therefore, there is not a single method for the extraction of all metals. However, most of the metals can be extracted by a general procedure which involves the following steps.

Various steps involved in metallurgical processes are

(a) Crushing and grinding of the ore.

(b) Concentration of the ore or enrichment of the ore.

(c) Extraction of metal from the concentrated ore.

(d) Refining or purification of the impure metal.

CRUSHING AND GRINDING OF ORE:

Those ores occur in nature as huge lumps. They are broken to small pieces with the help of crushers or grinders. These pieces are then reduced to fine powder with the help of a ball mill or stamp mill. This process is called pulverisation.

Concentration or dressing of the ore: The ore are usually obtained from the ground and therefore contained large amount of unwanted impurities, e.g., earthing particles, rocky matter, sand, limestone etc. These impurities are known collectively as gangue or matrix. It is essential to separate the large bulk of these impurities from the ore to avoid bulk handling and in subsequent fuel costs. The removal of these impurities from the ores is known as concentration. The concentration is done by physical as well as chemical methods. The various methods used for the enrichment of ores are explained below:

HYDRAULIC WASHING:

It is used for the enrichment of oxide ores. It is based on the difference in the densities of the gangue and the ore particles. The gangue particles are generally lighter as compared to ore particles. In this process, the crushed and finely powdered ore is washed with a stream of water. The lighter gangue particles are washed away, leaving behind the heavier ore particles.

Froth floatation process:

It is used to separate the gangue from the sulphide ores, especially those of copper, zinc and lead. In this process, the finely powdered ore is mixed with water in a large tank to form a slurry. Then some pine oil is added to it. The sulphide ores are preferentially wetted by the pine oil, whereas the gangue particles are wetted by the water. When air is blown through the mixture, the lighter oil froth carrying the metal sulphides rises to the top of the tank and floats as scum. It is then skimmed off and dried. The gangue particles being heavier, sink to the bottom of the tank.

ELECTROMAGNETIC SEPARATION:

It is used to enrich the magnetic ores (iron ore). The separation is done by using magnetic separators. A magnetic separator consists of a leather belt that moves over two rollers, out of which one is an electromagnet. The finely powdered ore is dropped over the moving belt at one end. When the ore falls down from the moving belt at the other end, the magnetic portion in the ore is attracted by the magnet and forms a heap nearer to the roller. The non-magnetic impurities fall away from the magnetic ore and form a separate heap.

Magnetic separation: The finely powdered ore is dropped over a moving belt which passes over magnetic roller. The particles attracted by the magnet form a separate pile.

CHEMICAL SEPARATION:

The process of chemical separation makes use of differences between the chemical properties of the gangue and the ore.

For example, Bauxite, Al2O3 . 2H2O, is an impure form of Aluminium oxide. The impurities mainly present in it are iron (III) oxide (Fe2O3) and sand (SiO2). The iron (III) oxide gives it a brown-red colour. Baeyer’s method is used to obtain pure Aluminium oxide from bauxite ore. In this method, the finely powdered ore is treated with hot sodium hydroxide solution. The aluminium oxide present in bauxite ore reacts with sodium hydroxide to form water soluble sodium aluminate.

Al2O3(s) + 2NaOH (aq) → 2NaAlO2 (aq) (Sodium aluminate) + H2O(l)

(From impure bauxite ore)

Iron (III) oxide does not dissolve in sodium hydroxide solution. It is, thus, separated by filtration. Silica reacts with sodium hydroxide to form water soluble sodium silicate.

SiO2 + 2NaOH → Na2 SiO3 (Sodium silicate) + H2O

The filtrate containing sodium aluminate and sodium silicate is then stirred with some aluminium hydroxide to induce the precipitation of aluminium hydroxide. The impurity, silica, remains dissolved as sodium silicate in the solution.

Na AlO2 (aq) + 2H2O (l) → Al(OH)3(s) (Aluminium hydroxide) + NaOH(aq)

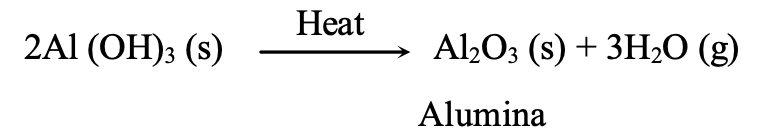

Aluminium hydroxide is then filtered off, washed, dried and ignited to get pure aluminium oxide, which is called alumina.

EXTRACTION OF THE METAL FROM THE CONCENTRATED ORE:

The metal is extracted from the concentrated ore by the following steps:

(a) Conversion of the concentrated ore into its oxide: The production of metal from the concentrated ore mainly involves reduction process. This can be usually done by two processes known as calcination and roasting process. The method depends upon the nature of the ore.

(b) Conversion of oxide to metal by reduction process

Conversion of Ore into Metal Oxide:

These are briefly discussed below:

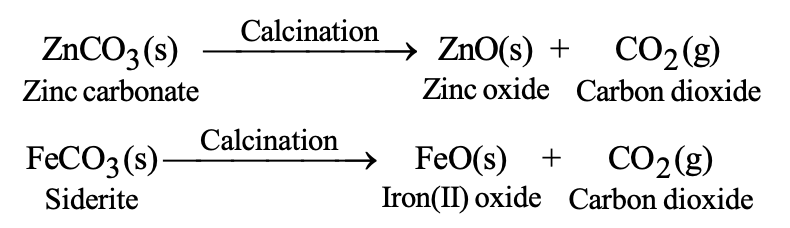

(i) Calcination: It is the process of heating the concentrated ore in the absence of air. The calcination process is used for the following changes:

- To convert carbonate ores into metal oxide.

- To remove water from the hydrated ores.

- To remove volatile impurities from the ore.

For example:

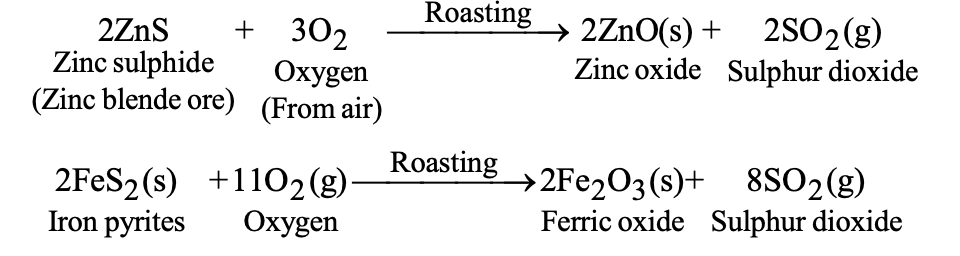

(ii) Roasting:

It is the process of heating the concentrated ore strongly in the presence of excess air.

This process is used for converting sulphide ores to metal oxide. In this process, the following changes take place:

- The sulphide ores undergo oxidation to their oxides.

- Moisture is removed.

- Volatile impurities are removed.

For example:

(b) Conversion of Metal Oxide to Metal

The metal oxide formed after calcination or roasting is converted into metal by reduction. The method used for reduction of metal oxide depends upon the nature and chemical reactivity of metal.

The metals can be grouped into the following three categories on the basis of their reactivity:

- Metals of low reactivity.

- Metals of medium reactivity.

- Metals of high reactivity.

These different categories of metals are extracted by different techniques. The different steps involved in separation are as follows:

(i) Reduction by heating: Metals placed low in the reactivity series are very less reactive. They can be obtained from their oxides by simply heating in air.