Class 10 History Notes – The Age of Industrialisation

The Class 10 History chapter, The Age of Industrialisation, explains how industrialization transformed societies, economies, and lifestyles in Europe and beyond. It highlights the beginnings of factories, the growth of industries, and their impact on workers and markets.

Pre-Industrial World

Before factories, industries were based on handicrafts and small workshops. Merchants often relied on craftsmen who worked from their homes. The proto-industrialisation phase was a key stage when trade networks expanded and goods were produced on a large scale before the rise of machines.

Industrial Revolution in Britain

Britain was the first country to experience industrialisation due to:

-

Abundant natural resources (coal and iron)

-

Strong colonial markets

-

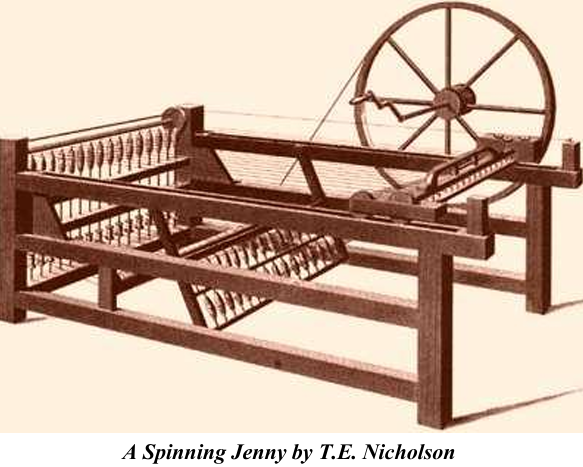

Technological innovations like the spinning jenny and the steam engine

-

Transport improvements, such as railways and canals

Growth of Factories

Factories replaced traditional hand production. Textile industries, especially cotton, expanded rapidly. Iron and steel industries also grew. Urban centers developed around factories, changing lifestyles and working patterns.

Life of Workers

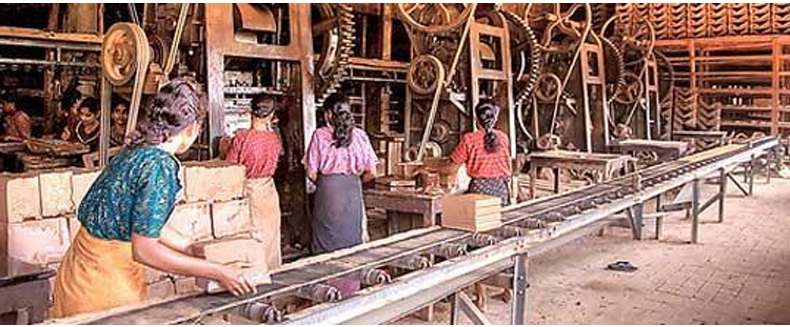

Workers faced long hours, poor wages, and unsafe conditions. Many women and children were also employed in industries. Strikes and protests became common as workers demanded better rights. Trade unions slowly emerged to protect workers’ interests.

Industrialisation Beyond Britain

-

Germany, France, and the USA soon became major industrial powers.

-

Colonies like India were forced to supply raw materials and act as markets for finished goods.

-

Handloom weavers in India suffered as British textiles flooded the market.

Impact of Industrialisation

-

Positive: Growth of technology, transport, communication, and mass production.

-

Negative: Harsh working conditions, environmental pollution, and unemployment for traditional artisans.

Importance for Class 10 Exams

This Class 10 chapter helps students understand the economic and social changes brought by industrialisation. Questions often come from:

-

Proto-industrialisation

-

Life of workers

-

Role of inventions

-

Impact on colonies like India

Quick Revision Notes – The Age of Industrialisation

-

Proto-industrialisation laid the foundation.

-

Britain led the Industrial Revolution.

-

Factories changed production and lifestyles.

-

Workers faced exploitation, leading to strikes.

-

Colonies were exploited for raw materials.

Introduction

Casual Wards: These were the night shelters set up by the Poor Law authorities.

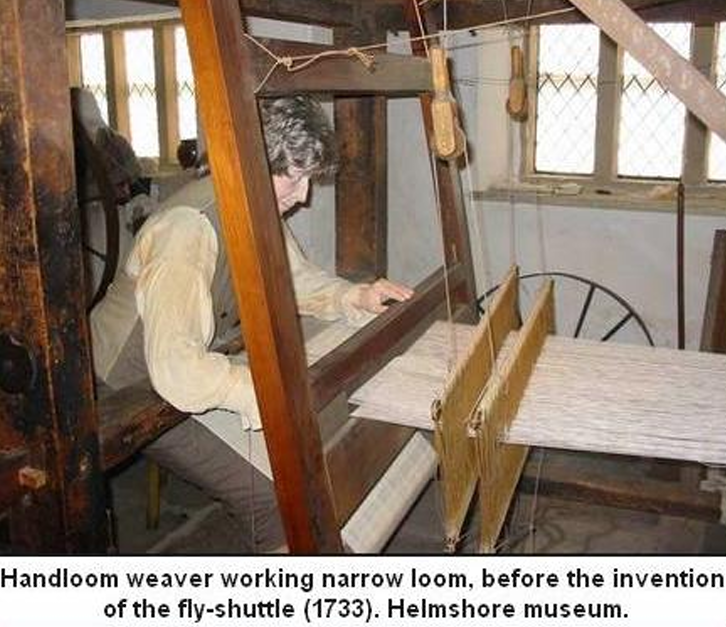

Fly shuttle: It is a mechanical device used for weaving, moved by means of ropes and pullies. It places the horizontal threads (called the weft) into the vertical threads (called the warp).

Metropolis: A large, density populated city of a country or state, often the capital of the region.

Night refugees: Shelters where jobseekers would spend their night; these were put up by private individuals.

Orient: The countries to the east of the Mediterranean, usually referring to Asia. The term arises out of a western viewpoint that sees this region as premodern, traditional and mysterious.

Sepoy: Refers to an Indian soldier in the service of the British.

Urbanization: Development of a city or town.

Before the Industrial Revolution

Powerful Trade Guilds: In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, with the expansion of world trade and the acquisition of colonies in different parts of the world, the demand for goods began growing. But merchants could not expand production within towns. This was because here urban crafts and trade guilds were powerful. These were associations of producers that trained craftspeople, maintained control over production, regulated competition and prices, and restricted the entry of new people into the trade. Rulers granted different guilds the monopoly right to produce and trade in specific products. It was therefore difficult for new merchants to set up business in towns.

Merchants from the towns in Europe began moving to the countryside, supplying money to peasants and artisans, persuading them to produce for an international market.

the-age-of-industrialisation: In the countryside poor peasants and artisans began working for merchants. Cottagers and poor peasants who had earlier depended on common lands for their survival, gathering their firewood, berries, vegetables, hay and straw, had to now look for alternative sources of income. Many had tiny plots of land which could not provide work for all members of the household. So when merchants came around and offered advances to produce goods for them, peasant households eagerly agreed. By working for the merchants, they could remain in the countryside and continue to cultivate their small plots. Income from proto-industrial production supplemented their shrinking income from cultivation. It also allowed them a fuller use of their family labour resources.

Within this system a close relationship developed between the town and the countryside. Merchants were based in towns but the work was done mostly in the countryside. This proto-industrial system was thus part of a network of commercial exchanges. It was controlled by merchants and the goods were produced by a vast number of producers working within their family farms, not in factories. At each stage of production 20 to 25 workers were employed by each merchant. This meant that each clothier was controlling hundreds of workers.

The Coming up of the Factory

- The earliest factories in England came up by the 1730s. But it was only in the late eighteenth century that the number of factories multiplied.

- In 1970 Britain was importing 2.5 million pounds of raw cotton to feed its cotton industry. By 1787 this import soared to 22 million pounds.

- A series of inventions in the eighteenth century increased the efficiency of each step of the production process (carding, twisting and spinning, and rolling).

- Then Richard Arkwright created the cotton mill. Till this time, as you have seen, cloth production was spread all over the countryside and carried out within village households.

- Now costly new machines could be purchased, set up and maintained in the mills. Within the mills all the process were brought together under one roof and management.

- This allowed a more careful supervision over the production process, a watch over quality, and the regulation of labour, all of which had been difficult to do when production was in the countryside.

- In the early nineteenth century, factories increasingly become an intimate part of the English landscape.

The Pace of Industrial Change:

- Main industries: Cotton and metal industries were the most dynamic industries in Britain. Cotton was the leading sector in the first phase of industrialisation up to the 1840s but the iron and steel industry led the way after 1840. By 1873 Britain was exporting iron and steel worth about $77 million, double the value of its cotton export.

- Domination of traditional industry: The modern machinery and, industries could not easily displace traditional industries. Even at the end of the nineteenth century, less than 20 percent of the total work force was employed in technologically advanced industrial sectors.

- Base for growth: The pace of change in the 'traditional' industries was not set by steam powered cotton or metal industries. It was the ordinary and small innovation which built up the basis of growth in many non-mechanised sectors.

- Slow pace: Though technological inventions were taking place but their pace was very slow. They did not spread dramatically across the industrial landscape. New technologies and machines were expensive so the producers and the industrialists were cautious about using them. The machines often broke down and repair was Costly. They were not as effective as their inventors and manufacturers claimed.

Coexistence of Hand Labour and Stream Power:

In Victorian Britain there was no shortage of human labour. Poor peasants and vagrants moved to the cities in large numbers in search of jobs, waiting for work.

So industrialists had no problem of labour shortage or high wage costs. They did not want to introduce machines that got rid of human labour and required large capital investment.

In many industries the demand for labour was seasonal. Gas works and breweries were especially busy through the cold months. So they needed more workers to meet their peak demand. Bookbinders and printers, catering to Christmas demand, too needed extra hands before December. At the waterfront, winter was the time that ships were repaired and spruced up. In all such industries where production fluctuated with the season, industrialists usually preferred hand labour, employing workers for the season.

Popularity of Intricate Designs:

A range of products could be produced only with hand labour. Machines were oriented to producing uniforms, standardised goods for a mass market. But the demand in the market was often for goods with intricate designs and specific shapes. In mid-nineteenth-century Britain, for instance, 500 varieties of hammers were produced and 45 kinds of axes. These required human skill, not mechanical technology.

In Victorian Britain, the upper classes – the aristocrats and the bourgeoisie – preferred things produced by hand. Handmade products came to symbolise refinement and class. They were better finished, individually produced, and carefully designed. Machine-made goods were for export to the colonies.

In countries with labour shortage, industrialists were keen on using mechanical power so that the need for human labour can be minimised. This was the case in nineteenth-century America. Britain, however, had no problem hiring human hands.

Life of the Worksers:

The process of industrialisation brought with it miseries for newly emerged class of industrial workers.

- Abundance of labour: As news of possible jobs travelled to the countryside, hundreds tramped to the cities. But everyone was not lucky enough to get an instant job. Many job-seekers had to wait weeks, spending nights under bridges or in night shelters. Some stayed in Night Refuge that was set up by private individuals; other went to the Casual Wards maintained by the Poor Law authorities.

- Seasonality of work: Seasonality of work in many industries meant prolonged periods without work. After the busy season was over, the poor were on the streets again. They either returned to the countryside or looked for odd jobs, which till the mid-nineteenth century were difficult to find.

- Poverty and unemployment: At the best of times till the mid-nineteenth century, about 10% of the urban population was extremely poor which went up to anything between 35 and 75% during periods of economic slump. The fear of unemployment made workers hostile to the introduction of new technology. When the Spinning Jenny was introduced in the woollen industry, women who survived on hand spinning began attacking the new machines. After the 1840s, building activity intensified in the cities, opening up greater opportunities of employment.

Industrialization in the Colonies

The Age of Indian Textiles:

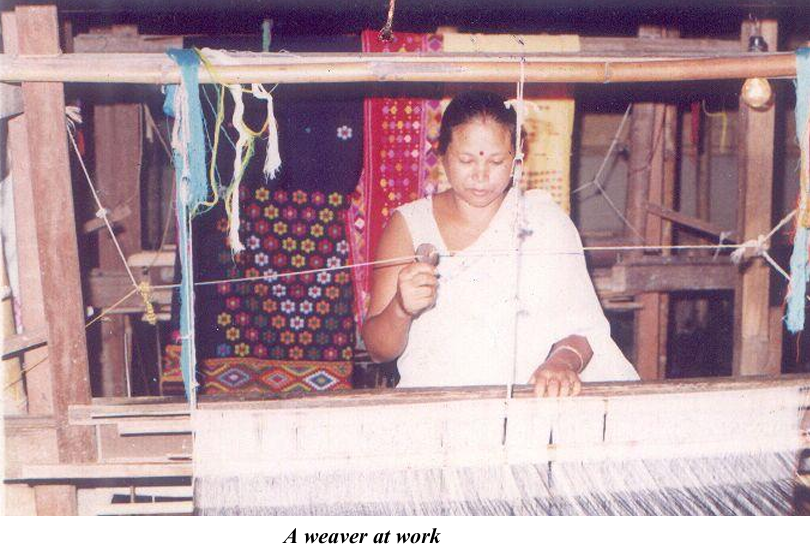

- Before the age of machine industries, silk and cotton goods from India dominated the international market in textiles.

- Fine variety of clothes was in great demand in the west.

- Armenian and Persian merchants took the goods from Punjab to Afghanistan, eastern Persia and Central Asia. Bales of fine textiles were carried on camel back via the north-west frontier, through mountain passes and across deserts.

- Surat on the Gujarat coast connected India to the Gulf and Red Sea Ports; Masulipatam on the Coromandel Coast and Hoogly in Bengal had trade links with Southeast Asian ports.

- A variety of Indian merchants and bankers were involved in this network of export trade – financing production, carrying goods and supplying exporters.

- The supply merchants linked the port towns to the inland region. They gave advances to the weavers, purchased the woven cloth from weaving villages, and brought the supply to the port.

- At the port, the big shippers and export merchants had brokers who negotiated the price and bought goods from the supply merchants operating inland.

Rise of European Companies:

The European companies gradually gained power – first securing a variety of concessions from local courts, then the monopoly rights to trade. This resulted in a decline of the old ports of Surat and Hoogly through which local merchants had operated. Exports from these ports fell dramatically, the credit that had financed the earlier trade began drying up, and the local bankers slowly went bankrupt.

In the last years of the seventeenth century, the gross value of trade that passed through Surat had been Rs 16 million. By the 1740s it had slumped to Rs 3 million. While Surat and Hoogly decayed, Bombay and Calcutta grew. This shift from the old ports to the new ones was an indicator of the growth of colonial power. Trade through the new ports came to be controlled by European companies, and was carried in European ships. While many of the old trading houses collapsed, those that wanted to survive had to now operate within a network shaped by European trading companies.

What Happened to Wearvers?

Before establishing political power in Bengal and Carnatic in the 1760s and 1770s, the East India Company had found it difficult to ensure a regular supply of goods for export. Once the East India Company established political power, it could assert a monopoly right to trade. It proceeded to develop a system of management and control that would eliminate competition, control costs, and ensure regular supplies of cotton and silk goods. This it did through a series of steps.

- The Company tried to eliminate the existing traders and brokers by appointing paid servants called the gomastha to supervise weavers, collect supplies, and examine the quality of cloth.

- It prevented Company weavers from dealing with other buyers by the system of advances. Once an order was placed, the weavers were given loans to purchase the raw material for their production. Those who took loans had to hand over the cloth they produced to the gomastha.

Effects

- Many weavers had small plots of land which they had earlier cultivated along with weaving, but now they had to lease out the land and devote all their time to weaving.

- In many weaving villages there were reports of clashes between weavers and gomastha. The gomasthas acted arrogantly, marched into villages with sepoys and peons, and punished weavers for delays in supply - often beating and flogging them. The weavers lost the space to bargain for prices and sell to different buyers, and the loans they had accepted tied them to the Company.

- In many places in Carnatic and Bengal, weavers deserted villages and migrated, setting up looms in other villages where they had some family relation. Elsewhere, weavers along with the village traders revolted, began refusing loans, closing down their workshops and taking to agricultural labour.

Clashes between Weaver and Gomasthas

- Earlier supply merchants had very often lived within the weaving village, and had a close relationship with the weavers, looking after their needs and helping them in times of crisis.

- The new gomasthas were outsiders, with no long-term social link with the village.

- They acted arrogantly, marched into villages with sepoys and peons, and punished weavers for delays in supply-often beating and flogging them.

- The weavers lost the space to bargain for prices and sell to different buyers : the price they received from the Company was miserably low and the loans they had accepted tied them to the Company.

- In many places in Carnatic and Bengal, weavers deserted villages and migrated, setting up looms in other villages where they had some family relation.

- At other places weavers and the local traders revolted against gomasthas and company officials.

East India Company

However, once the East India Company established political power, it could assert a monopoly right to trade. It proceeded to develop a system of management and control that would eliminate competition, control costs, and ensure regular supplies of cotton and silk goods. This it did through a series of steps.

- The Company tried to eliminate the existing traders and brokers connected with the cloth trade, and establish a more direct control over the weaver. It appointed a paid servant called the gomastha to supervise weavers, collect supplies, and examine the quality of cloth.

- It prevented Company weavers from dealing with other buyers. One way of doing this was through the system of advances. Once an order was placed, the weavers were given loans to purchase the raw material for their production. Those who took loans had to hand over the cloth they produced to the gomastha. They could not take it to any other trader.

As loans flowed in and the demand for fine textiles expanded, weavers eagerly took the advances, hoping to earn more. Many weavers had small plots of land which they had earlier cultivated along with weaving, and the produce from this took care of their family needs. Now they had to lease out the land and devote all their time to weaving. Weaving, in fact, required the labour of the entire family, with children and women all engaged in different stages of the process.

Soon, however, in many weaving villages there were reports of clashes between weavers and gomasthas. Earlier supply merchants had very often lived within the weaving villages, and had a close relationship with the weavers, looking after their needs and helping them in times of crisis. The new gomasthas were outsiders, with no long-term social link with the village. They acted arrogantly, marched into villages with sepoys and peons, and punished weavers for delays in supply – often beating and flogging them. The weavers lost the space to bargain for prices and sell to different buyers: the price they received from the Company was miserably low and the loans they had accepted tied them to the Company.

In many places in Carnatic and Bengal, weavers deserted villages and migrated, setting up looms in other villages where they had some family relation. Elsewhere, weavers along with the village traders revolted, opposing the Company and its officials. Over time many weavers began refusing loans, closing down their workshops and taking to agricultural labour.

Goods from Manchester

In 1772, Henry Patullo, a Company official, had ventured to say that the demand for Indian textiles could never reduce, since no other nation produced goods of the same quality. Yet by the beginning of the nineteenth century we see the beginning of a long decline of textile exports from India. In 1811-12 piece-goods accounted for 33 per cent of India's exports; by 1850-51 it was no more than 3 per cent.

As cotton industries developed in England, industrial groups began worrying about imports from other countries. They pressurized the government to impose import duties on cotton textiles so that Manchester goods could sell in Britain without facing any competition from outside. At the same time industrialists persuaded the East India Company to sell British manufactures in Indian markets as well. Exports of British cotton goods increased dramatically in the early nineteenth century. At the end of the eighteenth century there had been virtually no import of cotton piece-goods into India. But by 1850 cotton piece-goods constituted over 31 per cent of the value of Indian imports; and by the 1870s this figure was over 50 per cent.

Pproblems faced by Cotton Weavers:

- Cotton weavers in India thus faced two problems at the same time : their export market collapsed, and the local market shrank, being flooded with Manchester imports.

- Produced by machines at lower costs, the imported cotton goods were so cheap that weavers could not easily compete with them.

- By the 1850s, reports from most weaving regions of India narrated stories of decline and desolation.

- By the 1860s, weavers faced a new problem. They could not get sufficient supply of raw cotton of good quality. When the American Civil War broke out and cotton supplies from the US were cut off, Britain turned to India. As raw cotton export from India increased, the price of raw cotton shot up.

- Weavers in India were starved of supplies and forced to buy raw cotton at very high prices.

- By the end of the 19th century factories were established in India also. They also flooded the market with cheap factory made clothes. This was yet another problem faced by the weavers.

Beginning of Fators:

The first cotton mill in Bombay came up in 1854 and it went into production two years later. By 1862 four mills were at work with 94,000 spindles and 2,150 looms. Around the same time jute mills came up in Bengal, the first being set up in 1855 and another one seven years later, in 1862. In north India, the Elgin Mill was started in Kanpur in the 1860s, and a year later the first cotton mill of Ahmedabad was set up. By 1874, the first spinning and weaving mill of Madras began production.

The Early Enterpreneurs:

- The history of many business groups goes back to trade with China. From the late eighteenth century, the British in India began exporting opium to China and took tea from China to England. Many Indians became junior players in this trade, providing finance, procuring supplies, and shipping consignments. Having earned through trade, some of these businessmen had visions of developing industrial enterprises in India. Dwarkanath Tagore (Bengal), Dinshaw Petit and Jamsetjee Nusserwanjee Tata (Bombay), Seth Hukumchand and the father as well as grandfather of the famous industrialist G.D.Birla, all made their fortune in the China trade.

- Capital was accumulated through other trade networks. Some merchants from Madras traded with Burma while others had links with the Middle East and East Africa. There were yet other commercial groups which operated within India, carrying goods from one place to another, banking money, transferring funds between cities, and financing traders. When opportunities of investment in industries opened up, many of them set up factories.

- As colonial control over Indian trade tightened, the space within which Indian merchants could function became increasingly limited. They were barred from trading with Europe in manufactured goods, and had to export mostly raw materials and food grains. They were also gradually edged out of the shipping business.

- Till the First World War, European Managing Agencies in fact controlled a large sector of Indian industries. These Agencies mobilised capital, set up joint-stock companies and managed them. In most instances Indian Financiers provided the capital while the European Agencies made all investment and business decisions. The European merchant-industrialists had their own chambers of commerce which, businessmen were not allowed to join.

Migrations for Employment Opprtunities

Factories needed workers. With the expansion of factories, this demand increased. In 1901, there were 584,000 workers in Indian factories. By 1946 the number was over 2,436, 000.

In most industrial regions workers came from the districts around. Peasants and artisans who found no work in the village went to the industrial centres in search of work. Over 50 per cent workers in the Bombay cotton industries in 1911 came from the neighbouring district of Ratnagiri, while the mills of Kanpur got most of their textile hands from the villages within the district of Kanpur. Most often millworkers moved between the village and the city, returning to their village homes during harvests and festivals.

Over time, as news of employment spread, workers travelled great distances in the hope of work in the mills. From the United Provinces (Modern UP or Uttar Pradesh), for instance, they went to work in the textile mills of Bombay and in the jute mills of Calcutta.

Getting jobs was always difficult, even when mills multiplied and the demand for workers increased. The numbers seeking work were always more than the jobs available. Entry into the mills was also restricted. Industrialists usually employed a jobber to get new recruits. Very often the jobber was an old and trusted worker. He got people from his village, ensured them jobs, helped them settle in the city and provided them money in times of crisis. The jobber therefore became a person with some authority and power. He began demanding money and gifts for his favour and controlling the lives of workers.

The Perculiarities of Industrial Growth:

- European Managing Agencies, which dominated industrial production in India, were interested in certain kinds of products. They established tea and coffee plantations, acquiring land at cheap rates from the colonial government; and they invested in mining, indigo and jute.

- When Indian businessmen began setting up industries in the late nineteenth century, they avoided competing with Manchester goods in the Indian market.

- By the first decade of the twentieth century a series of changes affected the pattern of industrialisation. Industrial groups organised themselves to protect their collective interests, pressurising the government to increase tariff protection and grant other concessions.

- Till the First World War, industrial growth was slow. The war created a dramatically new situation. With British mill busy with war production to meet the needs of the army, Manchester imports into India declined. Suddenly, Indian mills had a vast home market to supply. As the war prolonged, Indian factories were called upon to supply war needs. New factories were set up and old ones ran multiple shifts. Many new workers were employed and everyone was made to work longer hours. Over the war years industrial production boomed.

- After the war, within the colonies, local industrialists gradually consolidated their position, substituting foreign manufactures and capturing the home market.

Dominance of Small Scale Industries:

While factory industries grew steadily after the war, large industries formed only a small segment of the economy. Most of them – about 67 per cent in 1911 – were located in Bengal and Bombay.

Over the rest of the country, small-scale production continued to predominate. Only a small proportion of the total industrial labour force worked in registered factories: 5 per cent in 1911 and 10 per cent in 1931. The rest worked in small workshops and household units, often located in alleys and bylanes, invisible to the passer-by. In fact, in some instances, handicrafts production actually expanded in the twentieth century. This is true even in the case of the handloom sector that we have discussed. While cheap machine-made thread wiped out the spinning industry in the nineteenth century, the weavers survived, despite problems. In the twentieth century, handloom cloth production expanded steadily: almost trebling between 1900 and 1940.

This was partly because of technological changes. Handicrafts people adopt new technology if that helps them improve production without excessively pushing up costs. So, by the second decade of the twentieth century we find weavers using looms with a fly shuttle. This increased productivity per worker, speeded up production and reduced labour demand. By 1941, over 35 per cent of handlooms in India were fitted with fly shuttles: in regions like Travancore, Madras, Mysore, Cochin, Bengal the proportion was 70 to 80 per cent. There were several other small innovations that helped weavers improve their productivity and compete with the mill sector.

Certain groups of weavers were in a better position than others to survive the competition with mill industries. Amongst weavers some produced coarse cloth while others wove finer varieties. The coarser cloth was bought by the poor and its demand fluctuated violently. In times of bad harvests and famines, when the rural poor had little to eat, and their cash income disappeared, they could not possibly buy cloth. The demand for the finer varieties bought by the well-to-do was more stable. The rich could buy these even when the poor starved. Famines did not affect the sale of Banarasi or Baluchari saris. Moreover, as you have seen, mills could not imitate specialised weaves. Saris with woven borders, or the famous lungis and handkerchiefs of Madras, could not be easily displaced by mill production.

Weavers and other craftspeople who continued to expand production through the twentieth century, did not necessarily prosper. They lived hard lives and worked long hours. Very often the entire household – including all the women and children – had to work at various stages of the production process. But they were not simply remnants of past times in the age of factories. Their life and labour was integral to the process of industrialisation.

Markets for Goods:

British manufacturers attempted to take over the Indian market on the other hand Indian weavers and craftsmen, traders and industrialists resisted colonial controls, demanded tariff protection, created their own spaces, and tried to extend the market for their produce.

(a) Methods Used by Producers to Expand their Markets:

- Advertisement: Advertisements make products appear desirable and necessary. They try to shape the minds of people and create new needs. From the very beginning of the industrial age, advertisements have played a part in expanding the markets for products, and in shaping a new consumer culture.

- Labeling: When Manchester industrialists began selling cloth in India, they put labels on the cloth bundles. The label was needed to make the place of manufacture and the name of the company familiar to the buyer. The label was also to be a mark of quality. When buyers saw 'MADE IN MANCHESTER' written in bold on the label, they were expected to feel confident about buying the cloth. Labels also carried images and were very often beautifully illustrated.

- Calendars: By the nineteenth century, manufacturers were printing calendars to popularise their products. Unlike newspapers and magazines, calendars were used even by people who could not read. They were hung in tea shops and in poor people's homes just as much as in offices and middle-class apartments. And those who hung the calendars had to see the advertisements, day after day, through the year. Even in these calendars images of gods and goddesses were used to attract the consumers.

- Images of gods, goddesses and personages: Images of Indian gods and goddesses regularly appeared on labels. It was as if the association with gods gave divine approval to the goods being sold, was also intended to make the manufacture from a foreign land appear somewhat familiar to Indian people. Like the images of gods, figures of important personages, of emperors and nawabs, adorned advertisements and calendars. The message: if your respect the royal figure, then respect this product; when the product was being used by kings, or produced under royal command, its quality could not be questioned.

- Advertisement by Indian producers: When Indian manufacturers advertised the nationalist message was clear and loud. If you care for the nation then buy products that Indians produce. Advertisements became a vehicle of the nationalist message of Swadeshi.

Summary

- Protective Tariff - To stop the import of certain goods and to protect the domestic goods a tariff was imposed. This tariff was imposed in order to save the domestic goods from the competition of imported goods and also to save the interest of local producers.

- Laissez, Faire - According to the economists, for the fast trade a policy of Laissez Faire should be applied whereby government should neither interfere in trade nor in the industrial production. This policy was introduced by a British economist named Adam Smith.

- Policy of Protection - The policy to be applied in order to protect the newly formed industry from stiff competition.

- Imperial preference - During British period, the goods imported from Britain to India be given special rights and facilities.

- Chamber of commerce - Chamber of commerce was established in the 19th century in order to take collective decisions on certain important issues concerning trade and commerce. Its first office was set up in Madras.

- Nationalist Message - Indian manufacturers advertised the nationalist message very clearly. They said, if you care for the national then buy products that Indians produce. Advertisement became a vehicle of nationalist message of Swadeshi.

The Age of Industrialization - Flow Chart

Age of Industrial Revolution

-

Marked by factory based system of production since 1730s in England.

-

Production at one place in factories.

-

Production in towns.

-

Supervision became Easy.

Proto-industrialization

-

Phase of industrialization before industrial revolution.

-

Production done is stages.

-

Final product assembled at finishing centres.

-

Production done mainly in country side.

Pace of Industrial change

-

It spread very slowly.

-

Initially confined to cotton and metal.

-

Could not displace handicraft completely.

-

Business men were not ready to adopt costly machines.

Industrialization in colonies

-

After gaining monopoly they destroyed Indian export.

-

Through gomasthas they got control of Indian weavers.

-

From exporter India became importer of cotton textile.

-

Still it could not destroy handicraft completely.

First World War and Growth of Indian Industries

-

British industries busy with war time production.

-

Indian industries got a chance to occupy local market.

-

Competition increased from Japanese and American.

-

British Industries could not capture the Indian market after the war.

Market for Goods

-

Various strategies were adopted to sell British made goods in India.

-

Made in Manchester were written in bold on labels.

-

Images of gods and goddess were printed.

-

Images of famous personalities like Nawabs, emperors were used.

Solved Questions

1. Name the sea routes that connected India with other Asian regions.

Ans. The prominent sea routes were as follows :

-

Surat on the Gujarat coast connected India to the Gulf and Red Sea Ports.

-

Masulipatnam on the Coromandel coast and Hoogly in Bengal had trade links with Southeast Asian ports.

2. What types of textiles did India export before the age of machine industries?

Ans. India exported finer varieties of textiles. Other countries primarily produced coarse quality of cloth.

3. What did the rise of ports at Bombay and Calcutta indicates?

Ans. The shift from the old port to the new ports was an indicator of the growth of the colonial power. These were controlled by the European companies. Goods were transported in the European ships.

4. Where did the workers for the upcoming new factories come from?

Ans. In most industrial regions, workers came from the districts around. Most often mill workers moved between the village and the city, they returned to their village homes during harvests and festivals.

5. What is the role of advertisements in the marketing of goods?

Ans. Advertisements play the following role in the marketing of goods:

-

Make the products appear desirable and necessary.

-

Try to shapes the minds of people and create new needs.

In short, advertisements help in expanding the markets for goods and in shaping a new consumer culture.

6. The European Managing Agencies were interested in which type of industries?

Ans. Tea and Coffee plantation.

7. "The technological changes occurred in the 19th century but they did not spread dramatically across the industrial landscapes." Explain

Ans. Technological changes did not spread dramatically. They were slow to be accepted. The following reasons account for this:

-

New technology was expensive, especially when seen against the background of the fact that labour was relatively cheaper. The machines often broke down. They required be maintaining and repairing. Repair was costly.

-

The machines were not found to be as effective as their inventors and manufactures claimed.

-

Machine could produce only standard size products. For products that required intricate design different shape machine based production was not suitable.

8. Discuss how international trade was carried on before the arrival of the Britishers.

Ans. A strong network of export trade had been established by the Indian merchants. They exercised an effective control over it.

-

Supply Merchants. They linked the port towns to the inland regions. They gave advances to weavers, procured the woven cloth from weaving villages, and carried the supply to the ports.

-

Brokers. They worked as intermediaries between the shippers and the merchants. They negotiated the price and bought goods from the supply merchants operating inland.

-

Shippers and Export Merchants undertook the job of shipping and transporting goods to the export destination.

9. Explain the results of First World War on Indian industries?

Ans. The First World War gave a great boost to the Indian industries because of the following reasons:

-

The British mills became busy with the production of war materials so all its export to India virtually stopped.

-

Suddenly, Indian mills got clearance to produce different articles for the home market.

-

The Indian factories were called upon to supply various war related materials like jute bags, cloth for uniforms, tents and leather boots for the armed forces.

10. Why could not the British industries recapture their old hold on the Indian market after First World War?

Ans.

-

During the war days, the Indian industries had achieved much advancement and had captured the local market.

-

Countries like US, Germany and Japan began to give a tough competition to England industrialists.

-

War brought economic difficulties for Britain.

11. Why the poor peasants and artisans began working for merchants?

Ans. Rural artisans and peasants found it in their own interest to get into this network of commercial exchange. The following reasons account for it.

-

They had neither the resources nor the ability to tap the growing global market for manufactured products.

-

This was the time when the open fields were disappearing and common property resources were being enclosed. Peasants depended upon these opens fields and common property resources for gathering firewood, berries, vegetables hay and straw, in short for their basic survival. They had no alternative sources of income.

-

Some peasants had tiny pieces of land. These could no provide work fall all the members of the family.

-

Merchants offered them money to produce goods. This money lent stability to the farmers' income. They got alternative sources of income right at their doorstep. They could hope to make full use of family labour at their disposal.

12. Which industry was the first to develop in the era of factory production, and why?

Ans. Cotton textile industry was the first to develop in the era of factory production. A number of changes within the process of production enabled this industry to grow fast. Among these, we may specifically mention the following :

-

A series of inventions tool place in the eighteenth century. These directly influenced and benefited the process of production of cotton textile. Each step in the production chain, viz, carding, twisting, spinning and rolling, was benefited.

-

These enhanced the productivity of labour. Output per worker increased and thus, their incomes increased. Consequently, there was more incentive for labour to work in the industry.

-

Machines made it possible to produce strong threads and yarn.

-

Different processes of production under one roof brought them under one management. This allowed a more careful supervision over the production process, a watch over quality, and regulation of labour.

13. What were the various steps taken by the East India Company to gain a monopoly over textile exports from goods?

Ans. The Company had to face initial difficulties in procurement of textiles from the weavers. The weavers and merchants had a number of selling options in the form of the French, Dutch and Portuguese buyers. The sellers would exercise their best option.

This was a painful situation for the company. In order to procure regular supplies of cotton and silk textiles from India weavers, the company took the following steps.

-

It secured monopoly rights to trade between India and Europe. As a result, the other competitors were simply eliminated.

-

It tried to eliminate the existing traders and brokers connected with the cloth trade.

-

It established a more direct control over the weavers. For this purpose, it appointed an official called gomastha. A gomastha was a paid employee of the company. His job was to supervise weavers, collect supplies and examine the quality of cloth.

-

The company began making advance payments to the weavers against any order. These payments enabled weavers to purchase the required raw materials. The finished products had to be delivered to the company. These weavers were not allowed to sell their produce to anyone else.

This is how the complete network of cotton trade was brought under the control of the East India Company.

14. Describe the relations between weavers and gomasthas.

Ans.

-

Gomasthas were the paid servants of the East India Company. Their jobs was to supervise weavers, collect supplies and examine the quality of cloth. Gomasthas came to replace the earlier supply merchants.

-

The supply merchants very often lived within the village, and had a close relationship with the weavers. They looked after their needs and helped them in times of crisis.

-

Gomasthas were outside. They had no or little feel of the rural life. They acted arrogantly. They marched into villages with sepoys and peons. They punished weavers for delays in supply. They often beat and flogged them.

-

As a result, there were reports of frequent clashes between weavers and gomasthas.

15. Explain what is meant by proto-industrialisation. How was it different than the present factory-production?

Ans.

-

Proto-industrialization refers to the system of production that existed in Britain before the arrival of modern machine-run factories.

-

Production during this pre-modern industrial phase were run basically with the help of human labour. Human skill and dexterity was employed to produce world-class goods that were sold in international markets.

-

Production was done in the rural areas in stages. Merchants provided advances to peasants. At the end of the process produce was assembled in finishing centers and then sold in the international market.

16. In the 17th century, merchants from towns in Europe began employing peasants and artisans within the village. Explain this statement.

Ans. In the 17th century, merchants from towns in Europe began employing peasants and artisans within the villages. Merchants supplied money to peasants and artisans. They collected the produce and sold it in the international markets for huge profits.

Two reasons account for this development:

-

With expansion of world trade and acquisition of colonies in different parts of the world, the demand for goods was growing worldwide. Merchants wanted to make use of this opportunity and earn profits. This required that the volume of production be increased.

-

Production in towns could not be increased. Production in urban crafts was controlled by trade guilds. Trade guilds were associations of producers that trained crafts people, maintained control over production, regulated competition and prices and restricted the enter of new people into the trade.

-

Rules had granted different guilds the monopoly night to produce and trade is specific products. Obviously, merchants could not depend upon urban crafts for supplies of manufactured goods. They had no alternative but to fall back upon rural artisans and peasants.

17. "The port of Surat declined by the end of the 18th century." Explain.

Ans. By the 1750s, the network of export trade controlled by Indian merchants was breaking down. This was primarily due to the fact that

-

The European companies were gaining power. They had secured monopoly rights to trade.

-

The credit that had financed the earlier trade began drying up. As the old network of export trade broke down, the importance of Surat port correspondingly declined.

-

The European companies began to take more interest in development of ports at Bombay and Calcutta. This was done to reduce competition from other European companies at the Surat Port.

-

As the control of east India Company increased over Indian trade decline of Surat Port was in evitable.

18. Image that you have been asked to write an article for an encyclopaedia on Britain and the history of cotton. Write your piece using information from the entire chapter.

Ans.

-

Cotton textile industry has been the mainstay of the people since times immemorial, as it provides for the basic need of clothing. During the period of proto-industrialisation, before the advent of machine, cotton cloth was produced by hand labour.

-

Crafts were organized into trade guilds. The guilds provided training to workers, maintained control over production, regulated competition and prices, and restricted the entry of new people into trade.

-

Machine was introduced during the 1730s. By the late 18th century the number of cotton factories multiplied. A series of inventions helped in this process. The various activities in production were getting increasingly simplified.

-

Britain emerged as a leading producer of cotton textile. For its expanding industry Britain required raw cotton, and market for the manufactured produced. A large part of India had, by then, come under the British control. The Britishers encouraged the export of raw cotton from India, and the import of manufactured goods from England. This spelt a doom for Indian textile industry. The Indian industry could not face the competition from the British mills.

-

The First World War created a dramatically new situation. The British mills got busy with production to meet the needs of the army. A vast domestic Market was now available to Indian industry. New factories were set up and old ones ran multiple shifts.

19. Why did some industrialists in 19th century Europe prefer hand labour over machines?

Ans. In the 19th century Europe, many industrialists preferred hand labour over machines due to the following reasons:

-

Many industries were seasonal in nature. During season, there were under pressure goods to produce more to meet market demand. At other times, they did not have much to do. Such industries preferred hand labour and employed workers for the season.

-

A number of products could be produced only with hand labour. This was especially true of those products that involved intricate designs and specific shapes. Machines were designed to produce only uniform, standardized products for the mass market.

-

Upper classes preferred goods produced by hand. They were better finished, individually produced, and carefully designed. They symbolized refinement and class.

-

In short, in labour-abundant Britain, machine could not easily displace human labour. In labour-scarce America, it did.

20. "Women workers in Britain attacked the Spinning Jenny." Explain.

Ans. Spinning Jenny was devised by James Hargreaves in 1764. This machine speeded up the spinning process and reduced labour demand. By turning one single wheel, a worker could set in motion a number of spindles and spin several threads at the same time.

When the Spinning Jenny was introduced in the woollen industry in England, women workers began attacking the new machines. This was due to two reasons.

-

Hand spinning was the only mode of subsistence and survival for these workers.

-

Workers were afraid that they would be thrown out of jobs.

21. "East India Company appointed Gomasthas to supervise weavers in India". Explain the above statement.

Ans. East India company wanted a regular supply of cotton and silk to Britain and wanted to eliminate competition for this :

-

Company tried to eliminate existing traders and establish a direct control over weavers. For this it appointed gomastha, a paid servant, to supervise weaver, collect supplies and to maintain quality.

-

Gomasthas provided advances to the weavers to purchase raw material for production. In return weavers had to hand over the clothes to the gomasthas at a fixed price.

-

This way British industries got a regular supply of woven clothes at a price. Garment made from these clothes were then exported back to India.

EXERCISE – 1 (MULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS)

- First cotton mill was set up in 1854 at

(a) Surat (b) Ahmadabad (c) Bombay (d) Pune - The process in which fibers are prepared prior to spinning is called

(a) Stapling (b) Carding (c) Rolling (d) Spinning - Port which connected India to red sea ports was

(a) Hoogly (b) Masulipatnam (c) Surat (d) Bombay - During swadeshi movement

(a) Production of khadi clothes increased (b) British import in India declined

(c) Industrial groups organized themselves (d) All the above - During Proto-Industrialization production could not increase in towns due to

(a) Lack of labour (b) Lack of power (c) Lack of profit (d) Guild system - First effect of Industrialization was on

(a) Cotton (b) Metal industry (c) Railways (d) Iron and steel - Which was the finishing centre?

(a) London (b) Manchester (c) Bombay (d) Surat - Spinning Jenny was invented by

(a) Jame Watt (b) E.T. Paull (c) James Hargreaves (d) T.E. Nicholson - Demand of which type of clothes never declined

(a) British clothes (b) Coarse cloth

(c) Fine variety of clothes (d) None of the above - What percentage of Handloom in India were fitted with fly shuttle by 1940

(a) 20 (b) 25 (c) 30 (d) 35 - Who invented the cotton mill?

(a) John Arkwright (b) Richard Arkwright

(c) Thomous Arkwright (d) Roul Arkwright - When did modern factories emerge in England?

(a) 1814 (b) 1840 (c) 1861 (d) 1822 - What was the first symbol of the new era?

(a) Cotton (b) Iron (c) Coal (d) Paper - When was the first cotton mill set up in India?

(a) In 1864 (b) In 1827 (c) In 1874 (d) In 1884 - In 1900 which popular music publisher produced a music book?

(a) S.J. John (b) P.B. Mark (c) S.T. Bond (d) E.T. Poull - Which city of England developed as a finishing centre?

(a) Manchester (b) Cambridge (c) London (d) Nottingham - The first Jute mill was established in India in -

(a) In 1865 (b) In 1855 (c) In 1862 (d) In 1827 - The Tata-Iron-Steel Company was established in -

(a) 1906 (b) 1908 (c) 1907 (d) 1909 - An economic system in which the Government owns the means of production.

(a) Socialism (b) Capitalism (c) Liberalisation (d) Democracy - What was the name of the paid servant who was appointed by the English company to deal with the Indian weavers?

(a) Nomashta (b) Nawabs (c) Gomashta (d) Stapler

ANSWERS TO EXERCISE – 1

| 1. (c) | 2. (b) | 3. (c) | 4. (d) | 5. (d) |

| 6. (a) | 7. (a) | 8. (c) | 9. (b) | 10. (d) |

| 11. (b) | 12. (b) | 13. (d) | 14. (d) | 15. (d) |

| 16. (c) | 17. (b) | 18. (c) | 19. (a) | 20. (c) |

EXERCISE – 2 (SHORT ANSWER QUESTIONS)

- What is proto-industrialisation?

- Who was the English industrialist to manufacture the new model of steam engine?

- Why did women oppose the introduction of Spinning Jenny?

- Why there were clashes between weavers and gomasthas?

- Name the European trading agencies which controlled a large sector on Indian industries.

- Why was the system of advancing loans to the weavers adopted by the English Company?

- What was the result of the import of Manchester cloth to India?

- Name some early Indian entrepreneurs of the 19th century in the field of industry and trade.

- Mention the images of gods/goddesses used to advertise the products in early 20th century.

- Why could not the British industries recapture their old hold on the Indian market?

- 'The abundance of labour in the market affected the lives of workers'. Explain it in the context of 18th century England.

- How was cotton production and distribution done in India before the machine age?

- Why did frequent clashes take place between weavers and Gomasthas appointed by the EIC?

- What was the impact of decline in cotton textiles of India on the native weavers?

- With what restrictions did the British tighten their control over Indian trade?

- In which products were the European Managing Agencies interested and why?

- Describe the series of changes that affected the pattern of industrialisation in the first decade of 20th century.

- Examine the chief feature of the Indian industrial development after World War-I.

- What methods were used to lure people to use new products? Explain.

- Explain the significance that 'Manchester label' had for the Indian consumer.

- Describe the important features of 'Proto industrialisation phase' in Europe.

- Explain the ways in which technological inventions shaped the production system in Britain. Give example.

- Explain the major features of the industrialisation process of Europe in the 19th century.

- Explain the strengths and weaknesses of the industrial development in England.

- Critically examine the process of industrialisation in Britain. Did all industries become mechanised? Explain.

- Critically examine the ways in which the lives of Indian workers changed due to industrialisation.

- Evaluate the role played by the early Indian entrepreneurs in industrialising India in the 19th century. Why did these opportunities become limited over the years?

- Explain the methods used by producers to expand their markets in the 19th century.