In-Depth Class 10 Circles Notes for Exam Preparation

Class 10 Circles Notes provide a comprehensive understanding of the properties, theorems, and practical applications of circles. These notes cover tangents, secants, chords, angle subtended by arcs, and cyclic quadrilaterals with detailed explanations and solved examples. Understanding circles is vital for geometry, trigonometry, and problem-solving in competitive exams. The notes include step-by-step methods to solve problems, shortcuts, and tips for remembering key properties. With structured practice exercises, students can improve their calculation speed, accuracy, and conceptual clarity. Circles appear frequently in board exams, so these notes help students revise effectively and tackle questions confidently. By practicing these notes, students gain a strong foundation in geometric reasoning, visualization, and analytical skills. Whether it is solving tangent problems or applying circle theorems, these notes are an essential resource for Class 10 students aiming for academic success. After reading the note, solving NCERT questions with the help of the NCERT Solutions for class 10 Maths will help in building the foundation.

Class 10 Circles Notes, Solved example & Questions

History of Circles

The word "circle" derives from the Greek, kirkos "a circle," from the base ker- which means to turn or bend. The origins of the words "circus" and "circuit" are closely related. The circle has been known since before the beginning of recorded history. Natural circles would have been observed, such as the Moon, Sun, and a short plant stalk blowing in the wind on sand, which forms a circle shape in the sand. The circle is the basis for the wheel, which, with related inventions such as gears, makes much of modern civilization possible.

In mathematics, the study of the circle has helped inspire the development of geometry, astronomy, and calculus. Early science, particularly geometry and astrology and astronomy, was connected to the divine for most medieval scholars, and many believed that there was something intrinsically "divine" or "perfect" that could be found in circles.

A circle is the locus of a point which moves in a plane in such a way that its distance from a fixed point remains constant.

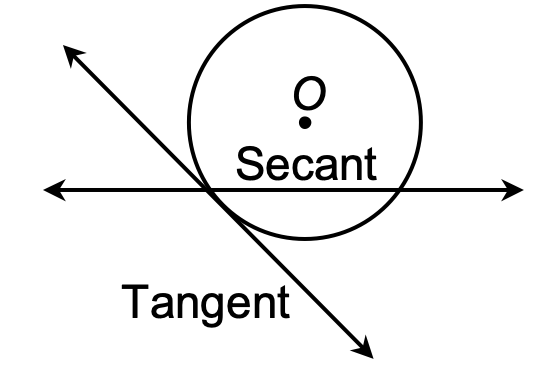

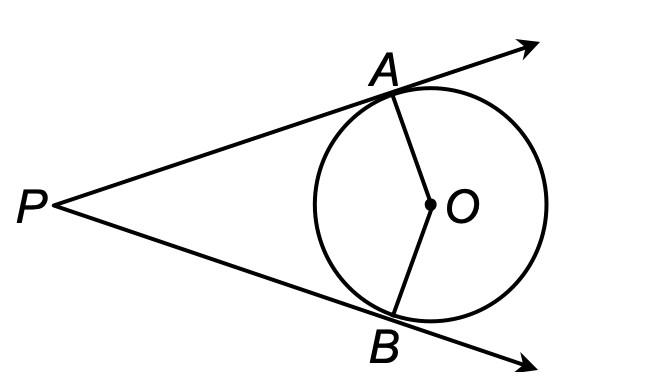

Secant

A line, which intersects a circle in two distinct points, is called a secant.

Tangent

A line meeting a circle only in one point is called a tangent to the circle at that point.

The point at which the tangent line meets the circle is called the point of contact.

Length of Tangent

The length of the line segment of the tangent between a given point and the given point of contact with the circle is called the length of the tangent from the point to the circle.

- There is no tangent passing through a point lying inside the circle.

- There is one and only one tangent passing through a point lying on a circle.

- There are exactly two tangents through a point lying outside a circle.

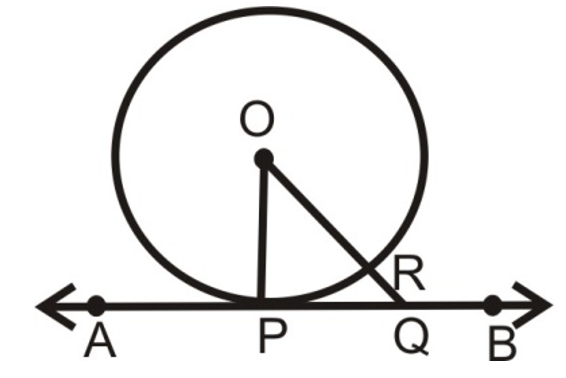

Theorem

A tangent to a circle i perpendicular to the radius through the point of contact.

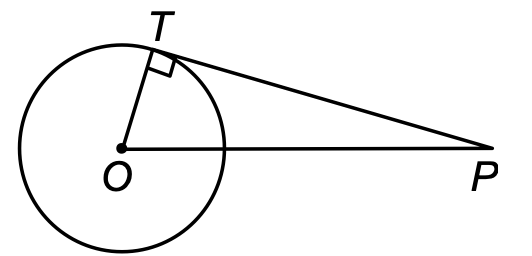

Given: A circle C (O, r) and a tangent AB at a point P.

To prove: OP AB

Construction: Take any points Q, other than P on the tangent AB. Join OQ. Suppose OQ meets the circle at R.

Proof: Among all line segments joining the point O to a point on AB, the shorted one is perpendicular to

AB. So, to prove that OP AB, it is sufficient to prove that OP is shorter than any other segment joining O to any point of AB.

Clearly OP = OR.

Now, OQ OR + RQ

OQ > OR

OQ > OP ( OP = OR)

Thus, OP is shorter than any other segment joining O to any point of AB.

Hence, OP AB.

Theorem

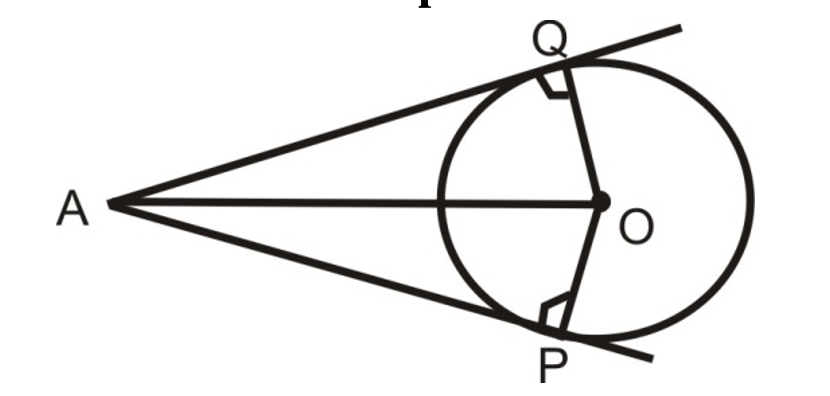

Lengths of two tangents drawn from an external point to a circle are equal.

[Diagram shows a circle with center O, and point A external to the circle. Two tangent lines are drawn from A to the circle, touching at points P and Q]

Given: AP and AQ are two tangents drawn from a point A to a circle C (O, r).

To prove: AP = AQ.

Construction: Join OP, OQ and OA.

Proof: In △AOQ and △APO

∠OQA = ∠OPA [Tangent at any point of a circle is perp. to radius through the point of contact]

AO = AO [Common]

OQ = OP [Radius]

So by R.H.S. criterion of congruency △AOQ ≅ △AOP.

∴ AQ = AP. [By CPCT] Hence Proved

Result:

(i) If two tangents are drawn to a circle from an external point, then they subtend equal angles at the centre. ∠OAQ = ∠OAP [By CPCT].

(ii) If two tangents are drawn to a circle from an external point, they are equally inclined to the segment, joining the centre to that point ∠OAQ = ∠OAP [By CPCT].

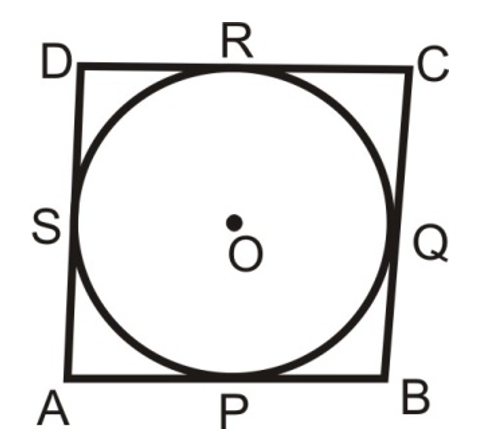

1. If all the sides of a parallelogram touches a circle, show that the parallelogram is a rhombus.

Sol.

Given: Sides AB, BC, CD and DA of a ||gm ABCD touch a circle at P, Q, R and S respectively.

To prove: ||gm ABCD is a rhombus.

Here's the text conversion with all mathematical symbols and expressions:

Proof:

AP = AS ......(i)

BP = BQ ......(ii)

CR = CQ ......(iii)

DR = DS ......(iv)

[Tangents drawn from an external point to a circle are equal]

Adding (1), (2), (3) and (4), we get

⇒ AP + BP + CR + DR = AS + BQ + CQ + DS

⇒ (AP + BP) + (CR + DR) = (AS + DS) + (BQ + CQ)

⇒ AB + CD = AD + BC

⇒ AB + AB = AD + AD [In a ‖gm ABCD, opposite side are equal]

⇒ 2AB = 2AD or AB = AD.

But AB = CD AND AD = BC [Opposite sides of a ‖ gem]

∴ AB = BC = CD = DA.

Hence, ‖gm ABCD is a rhombus.

2. From a point P, 10 cm away from the centre of a circle, a tangent PT of length 8 cm is drawn. Find the radius of the circle.

Sol. Let O be the centre of the given circle and let P be a point such that OP = 10 cm.

Let PT be the tangent such that PT = 8 cm.

Join OT.

Now PT is a tangent at T and OT is the radius through T.

[THIS IS FIGURE: A circle with center O, point P outside the circle, tangent PT touching the circle at point T, with a right angle marked at T between the radius OT and tangent PT]

∴ OT ⊥ PT [Radius is ⊥ to tangent at the point of contact]

In the right ΔOTP, we have

OP² = OT² + PT² [by Pythagoras' theorem]

⇒ OT = √(OP² - PT²) = √((10)² - (8)²) cm = √36 cm = 6 cm

Hence, the radius of the circle is 6 cm.

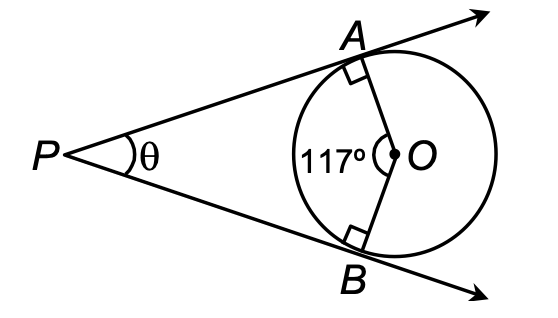

3. In the given figure, O is the centre of a circle; PA and PB, pair of tangents drawn to the circle from point P outside the circle. If ∠AOB = 117°, find θ.

[FIGURE: A diagram showing a circle with center O. Point P is outside the circle. Two tangent lines PA and PB are drawn from P to the circle, touching at points A and B respectively. The angle at P between the two tangents is marked as θ. The angle ∠AOB at the center is marked as 117°. The radius OA and OB are shown perpendicular to the tangents at points A and B.]

Sol.

In quad. AOBP, ∠A = ∠B = 90°. [Radius is ⊥ to tangent at the point of contact]

∴ ∠AOB + ∠APB = 180° [∵ sum of angles of quad. is 360°]

⇒ 117° + θ = 180°

⇒ θ = 180° - 117° = 63°

∴ θ = 63°.

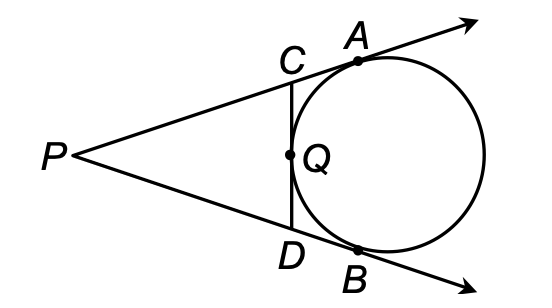

4. In the given figure, PA and PB are tangents to the circle drawn from an external point P. CD is another tangent touching the circle at Q. If PA = PB = 12 cm and QD = 3 cm, find the length of PD.

[FIGURE: A diagram showing a circle with center (not explicitly marked). Point P is external to the circle on the left side. Two tangent lines PA and PB are drawn from P to the circle, touching at points A (top) and B (bottom). A third tangent line CD passes through point C (above A) and point D (below B), touching the circle at point Q. The circle's center appears to be between points A and B.]

Sol.

Point D outside the circle. DQ and DB is the pair of tangents drawn to the circle from the point D.

⇒ DB = DQ

⇒ DB = 3 cm. (∵ QD = DQ = 3 cm is given)

Now, PD + DB = PB

⇒ PD + 3 cm = 12 cm (∵ PB = 12 cm is given)

⇒ PD = 9 cm.

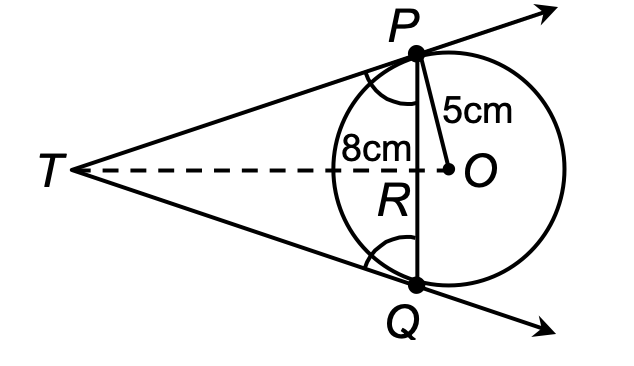

5. PQ is a chord of length 8 cm of a circle of radius 5 cm. The tangents at P and Q intersect at a point T. Find the length of TP.

[Diagram shows a circle with center O and radius 5 cm, chord PQ of length 8 cm, and tangent lines at P and Q intersecting at external point T]

Sol.

Let TP = x and TR = y.

ΔTPQ is isosceles Δ,

∴ TR is the ⊥ bisector of PQ,

∴ PR = RQ = 4 cm

Also, OR = √(OP² - PR²) = √(5² - 4²) = 3 cm.

In right Δ PRT, we have

x² = y² + 16. ... (i)

In right Δ OPT, we have

⇒ x² + 5² = (y + 3)² ... (ii)

Subtracting (i) from (ii), we have

25 = 6y - 7 or y = 32/6 = 16/3.

Therefore, x² = (16/3)² + 16 = 16/9(16 + 9) = (16 × 25)/9. [from equation (i)]

Or x = 20/3.

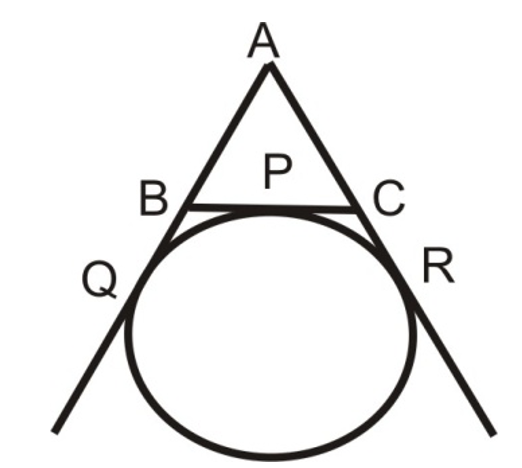

6. A circle touches the BC of a △ABC at P and touches AB and AC when produced at Q and R respectively as shown in the figure. Show that = 1/2 (Perimeter of △ABC).

Sol. Given: A circle is touching side BC of △ABC at P and touching AB and AC when produced at Q and R respectively.

[THIS IS FIGURE: A triangle ABC with a circle inscribed that touches BC at point P, and touches the extended lines AB and AC at points Q and R respectively]

To prove: AQ = 1/2 (perimeter of △ABC).

Proof: AQ = AR ......(i) BQ = BP ......(ii) CP = CR ........(iii)

[Tangents drawn from and external point to a circle are equal]

Now, perimeter of △ABC = AB + BC + CA = AB + BP + PC + CA = (AB + BQ) + (CR + CA) [From (ii) and (iii)] = AQ + AR = AQ + AQ [From (i)]

AQ = 1/2 (perimeter of △ABC).

7. Prove that the tangents at the extremities of any chord make equal angles with the chord.

Sol.

Let AB be a chord of a circle with centre O, and let AP and BP be the tangents at A and B respectively. Suppose, the tangents meet at point P. Join OP. Suppose OP meets AB at C.

[DIAGRAM: A circle with center O, chord AB, tangents at A and B meeting at point P, with OP intersecting AB at C]

We have to prove that ∠PAC = ∠PBC.

In triangles PCA and PCB

PA = PB [∵ Tangent from an external point are equal]

∠APC = ∠BPC. [∵ PA and PB are equally inclined to OP]

And PC = PC. [Common]

So, by SAS criteria of congruence

ΔPAC ≅ ΔBPC

⇒ ∠PAC = ∠PBC. [By CPCT]

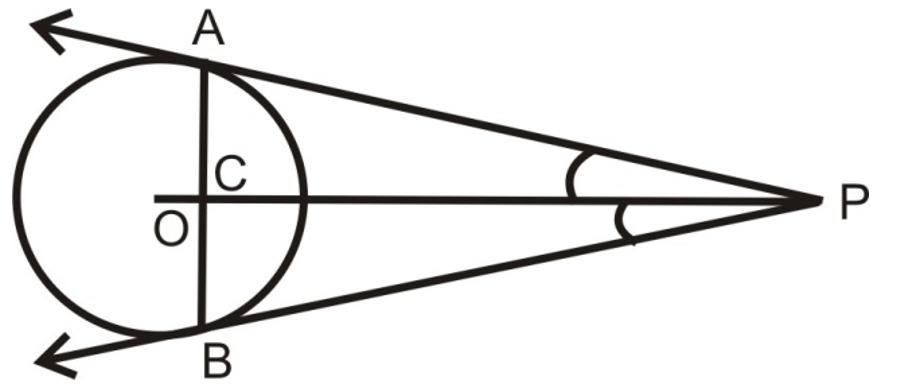

8. Prove that the segment joining the points of contact of two parallel tangents passes through the centre.

Sol.

Let PAQ and RBS be two parallel tangents to a circle with centre O. Join OA and OB. Draw OC||PQ. Now, PA||CO

[THIS IS FIGURE: A circle with center O, two parallel tangents PAQ (top) and RBS (bottom), points A and B as points of contact, point C to the left of O, and a vertical dashed line through A, O, and B]

⇒ ∠PAO + ∠COA = 180° [Sum of co-interior angle is 180°]

⇒ 90° + ∠COA = 180° [∵ ∠PAO = 90]

⇒ ∠COA = 90°.

Similarly, ∠COB = 90°.

∴ ∠COA + ∠COB = 90° + 90° = 180°.

Hence AOB is a straight line passing through O.

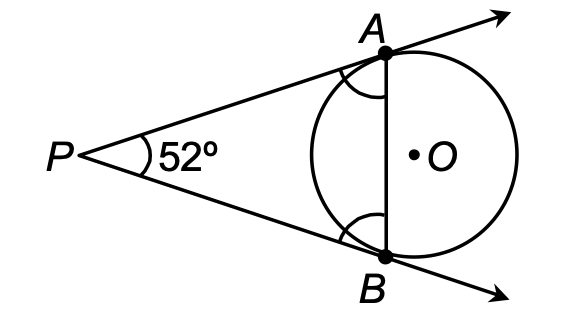

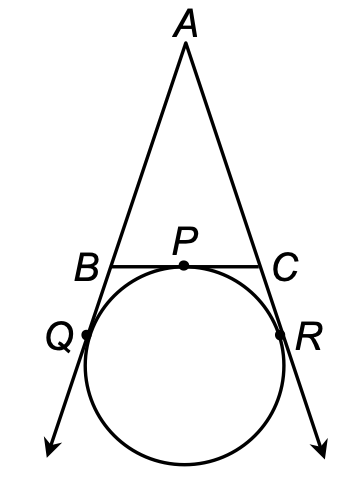

9. In the given figure, PA and PB is a pair of tangents drawn to a circle having its centre at O. If ∠APB = 52°, find the ∠PAB and ∠PBA.

[FIGURE: A diagram showing a circle with center O. Point P is external to the circle. Two tangent lines are drawn from P to the circle, touching at points A and B. The angle at P (∠APB) is marked as 52°. Lines PA and PB extend beyond the points of tangency.]

Sol. In ΔPAB,

PA = PB [Tangents from common point are equal in length]

⇒ ∠PAB = ∠PBA [Angles opposite to equal sides]

= 1/2 × (180° - 52°)

= 1/2 × 128° (∵ ∠PAB + ∠PBA + 52° = 180°)

⇒ ∠PAB = ∠PBA = 64°.

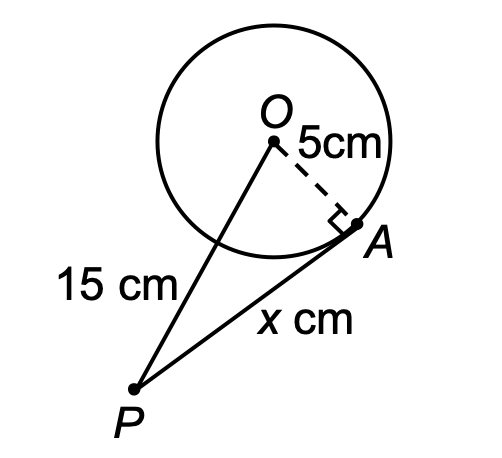

10. A point P is 15 cm from the centre of a circle. The radius of the circle is 5 cm. Find the length of the tangent drawn to the circle from the point P.

Sol. Let PA = x cm be the length of the tangent to the circle. OA is perpendicular to PA at A.

OA = 5 cm (radius)

OP = 15 cm (given).

[There is a diagram showing a circle with center O, radius 5 cm to point A on the circle, point P outside the circle at distance 15 cm from O, and a tangent line PA of length x cm from P to A]

By Pythagoras theorem,

OP² = PA² + OA²

⇒ (15)² = x² + (5)²

⇒ x² = 225 - 25 = 200

⇒ x = √200 = 10√2.

∴ Length of the tangent = 10√2 cm.

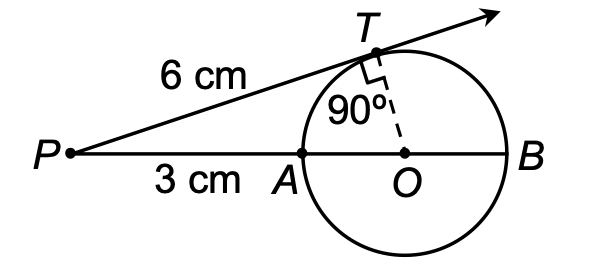

11. In the given figure O is the centre of the circle and PT is the tangent drawn from the point P to the circle. Secant PAB passes through the centre O of the circle. If PT = 6 cm and PA = 3 cm, then find the radius of the circle.

[FIGURE: A circle with center O. Point P is outside the circle. PT is a tangent to the circle at point T, with PT = 6 cm marked. A secant line PAB passes through P, A, and B, where AB is a diameter passing through center O. PA = 3 cm is marked. Angle OTP = 90° is shown.]

Sol.

In figure AB is a diameter of the circle and OA = r (radius of the circle). Join O & T. ∠OTP = 90°. [Radius is ⊥ to tangent at the point of contact]

In right angled ΔOTP, OP = OA + PA = (r + 3) cm.

By Pythagoras theorem,

OP² = OT² + PT²

⇒ (r + 3)² = r² + (6)²

⇒ r² + 6r + 9 = r² + 36

⇒ 6r = 27

⇒ r = 9/2 = 4.5

Hence, the radius of the circle = 4.5 cm

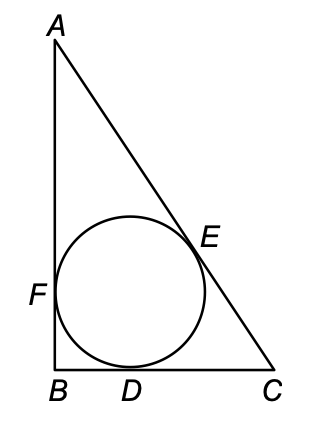

12. The incircle of ΔABC touches the sides BC, CA and AB at D, E and F, respectively. If AB = AC, prove that BD = CD.

Sol. Since tangents drawn from an external point to a circle are equal in length.

∴ AF = AE [Tangents from A] ..... (i)

BF = BD [Tangents from B] ..... (ii)

CD = CE [Tangents from C] ..... (iii)

[THIS IS FIGURE: A triangle ABC with an incircle. The incircle touches side BC at point D, side CA at point E, and side AB at point F. Points B, D, and C are shown on the bottom, with A at the top vertex.]

Adding (i), (ii) and (iii), we get

AF + BF + CD = AE + BD + CE

⇒ AB + CD = AC + BD

But AB = AC. [Given]

∴ CD = BD.

13. A circle is touching the side BC of a △ABC at P and touching AB and AC produced at Q and R respectively. Prove that AQ = 1/2 (Perimeter of △ABC).

Solution:

2AQ = AQ + AR (∵ AQ = AR) [Tangent from a common point]

= (AB + BQ) + (AC + CR) = AB + AC + (BQ + CR)

= AB + AC + (BP + CP) [∵ BQ = BP and CR = CP]

= AB + AC + BC = (Perimeter of △ABC)

[THIS IS FIGURE: A triangle ABC with a circle inscribed. The circle touches side BC at point P, and touches the extensions of sides AB and AC at points Q and R respectively. Points B, P, and C are marked along the bottom, with Q to the left and R to the right of the circle.]

⇒ AQ = 1/2 (Perimeter of △ABC).

14. Prove that the angle between the two tangents drawn from an external point to a circle is supplementary to the angle subtended by the line segments joining the points of contact to the centre.

Sol.

Given: PA and PB are the tangents drawn from a point P to a circle with centre O. Also, the line segments OA and OB are drawn.

To prove: ∠APB + ∠AOB = 180°.

Proof: We know that the tangent to a circle is perpendicular to the radius through the point of contact.

[THIS IS FIGURE: A diagram showing a circle with center O, external point P, two tangent lines PA and PB touching the circle at points A and B respectively, with radii OA and OB drawn to the points of contact]

∴ PA ⊥ OA ⇒ ∠OAP = 90°, and PB ⊥ OB ⇒ ∠OBP = 90°.

∴ ∠OAP + ∠OBP = (90° + 90°) = 180°.

Hence, ∠APB + ∠AOB = 180°. [∵ Sum of all the ∠s of a quadrilateral is 360°]

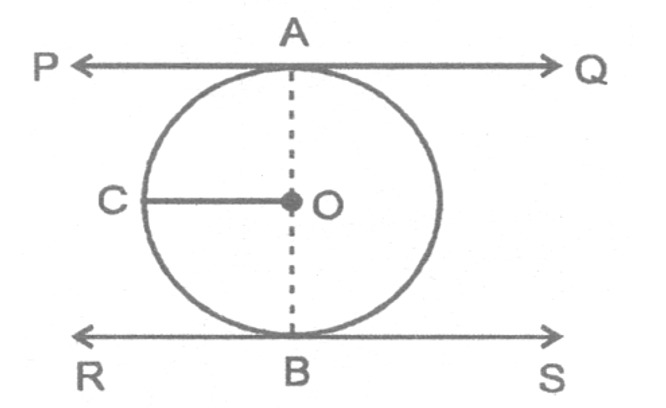

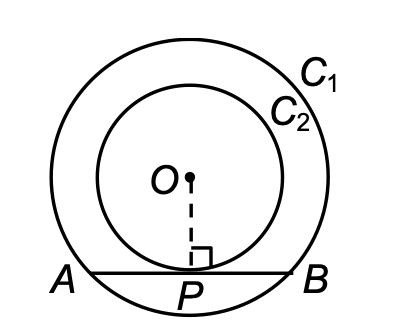

15. Prove that in two concentric circles, the chord of the larger circle, which touches the smaller circle, is bisected at the point of contact.

Sol. Let O be the common centre of two concentric circles C₁ and C₂ and a chord AB of the larger circle C₁ touching the smaller circle C₂ at the point P.

Join OP.

[DIAGRAM: Shows two concentric circles with center O, where C₂ is the smaller inner circle and C₁ is the larger outer circle. A horizontal chord AB of the larger circle touches the smaller circle at point P. A dashed line connects O to P vertically.]

Since OP is the radius of the smaller circle and AB is a tangent to this circle at a point P.

∴ OP ⊥ AB

The perpendicular drawn from the centre of a circle to any chord of the circle bisects the chord.

∴ AP = BP

Hence AB is bisected at the point of contact.