Comprehensive Class 10 Triangles Notes with Examples

Class 10 Triangles Notes cover all essential theorems, properties, and problem-solving techniques, including congruence, similarity, Pythagoras theorem, and properties of medians, altitudes, and angle bisectors. Each concept is explained with examples and practical applications for easier understanding. These notes help students learn step-by-step methods to solve triangle-related problems efficiently. Understanding triangles is fundamental for geometry, trigonometry, and real-life applications in construction and design. The notes also include tips for quick identification of triangle properties, shortcuts for solving congruence and similarity questions, and exam-focused practice problems. By following these notes, students can strengthen their reasoning and visualization skills, improve accuracy, and gain confidence in solving triangle-based questions in Class 10 board exams and competitive tests. Solving the NCERT questions with the help of the NCERT Solutions for class 10 Maths will help in building the foundation

Class 10 Triangles Notes, Solved example & Questions

Class 10 Triangles Notes cover all essential theorems, properties, and problem-solving techniques, including congruence, similarity, Pythagoras theorem, and properties of medians, altitudes, and angle bisectors. Each concept is explained with examples and practical applications for easier understanding. These notes help students learn step-by-step methods to solve triangle-related problems efficiently.

Understanding triangles is fundamental for geometry, trigonometry, and real-life applications in construction and design. The notes also include tips for quick identification of triangle properties, shortcuts for solving congruence and similarity questions, and exam-focused practice problems. By following these notes, students can strengthen their reasoning and visualization skills, improve accuracy, and gain confidence in solving triangle-based questions in Class 10 board exams and competitive tests. Solving the NCERT questions with the help of the NCERT Solutions for class 10 Maths will help in building the foundation

CONGRUENT AND SIMILAR FIGURES

Two geometric figures having the same shape and size are known as congruent figures. Geometric figures having the same shape but different sizes are known as similar figures.

SIMILAR TRIANGLES:

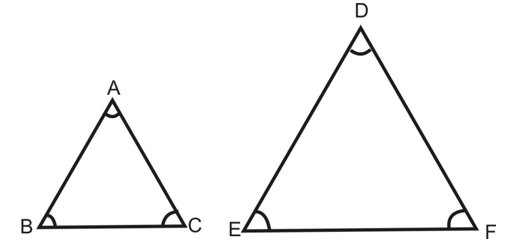

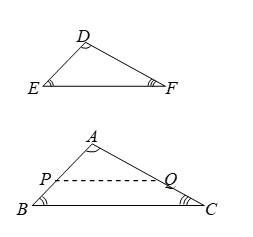

Two triangles ABC and DEF are said to be similar if their:

(i) Corresponding angles are equal.

i.e. ∠A = ∠D, ∠B = ∠E, ∠C = ∠F

And,

(ii) Corresponding sides are proportional i.e. AB/DE = BC/EF = AC/DF.

CHARACTERISTIC PROPERTIES OF SIMILAR TRIANGLES:

(i) (AAA Similarity) If two triangles are equiangular, then they are similar.

(ii) (SSS Similarity) If the corresponding sides of two triangles are proportional, then they are similar.

(iii) (SAS Similarity) If in two triangle's one pair of corresponding sides are proportional and the included angles are equal then the two triangles are similar.

RESULTS BASED UPON CHARACTERISTIC PROPERTIES OF SIMILAR TRIANGLES:

(i) If two triangles are equiangular, then the ratio of the corresponding sides is the same as the ratio of the corresponding medians.

(ii) If two triangles are equiangular, then the ratio of the corresponding sides is same at the ratio of the corresponding angle bisector segments.

(iii) If two triangles are equiangular then the ratio of the corresponding sides is same at the ratio of the corresponding altitudes.

(iv) If one angle of a triangle is equal to one angle of another triangle and the bisectors of these equal angles divide the opposite side in the same ratio, then the triangles are similar.

(v) If two sides and a median bisecting one of these sides of a triangle are respectively proportional to the two sides and the corresponding median of another triangle, then the triangles are similar.

(vi) If two sides and a median bisecting the third side of a triangle are respectively proportional to the corresponding sides and the median another triangle, then two triangles are similar.

BASIC PROPORTIONALITY THEOREM (THALES THEOREM)

THEOREM 1:

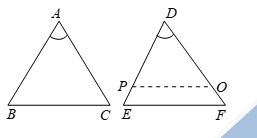

If a line is drawn parallel to one side of a triangle to intersect the other two sides in distinct points, the other two sides are divided in the same ratio.

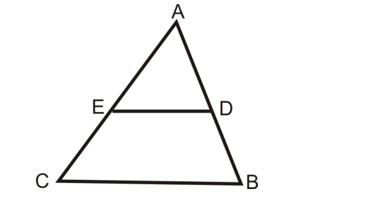

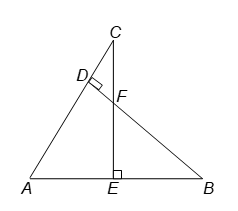

Given: A triangle ABC in which a line parallel to side BC intersects other two sides AB and AC at D and E respectively.4

To prove: AD/DB = AE/EC

Construction: Join BE and CD and draw DM ⊥ AC and EN ⊥ AB.

Proof: area of ∠ADE

(Taking AD as base)

So, ar(ADE) = 1/2 × AD × EN [The area of ∠ADE is denoted as ar(ADE)].

Similarly, ar(BDE) = 1/2 × DB × EN

and ar(ADE) = 1/2 × AE × DM (Taking AE as base)

Therefore, ar(ADE)/ar(BDE) = AD/DB ...(i)

and ar(ADE)/ar(DEC) = AE/EC ...(ii)

ar(BDE) = ar(DEC) ... (iii)

[∠BDE and DEC are on the same base DE and between the same parallels BC and DE.]

Therefore, from (i), (ii) and (iii), we have: AD/DB = AE/EC.

Corollary: From above equation we have AD/DB = AE/EC.

Adding '1' to both sides we have

AD/DB + 1 = AE/EC + 1

⇒ (AD + DB)/DB = (AE + EC)/EC

⇒ AB/DB = AC/EC.

Theorem 2 - Converse of BPT

THEOREM 2:

(Converse of BPT theorem)

Statement: If a line divides any two sides of a triangle in the same ratio, prove that it is parallel to the third side.

Given: In ∠ABC, DE is a straight line such that AD/DB = AE/EC.

To prove: DE || BC.

Construction: If DE is not parallel to BC, draw DF meeting AC at F.

Proof:

In ∠ABC, let DF || BC

AD/DB = AF/FC ...(i)

[A line drawn parallel to one side of a ∠ divides the other two sides in the same ratio.]

But AD/DB = AE/EC ...(ii) [given]

From (i) and (ii), we get

AF/FC = AE/EC.

Adding 1 to both sides, we get

(AF + FC)/FC = (AE + EC)/EC

AC/FC = AC/EC

FC = EC.

It is possible only when E and F coincide

Hence, DE || BC.

SOME IMPORTANT RESULTS AND THEOREMS:

- The internal bisector of an angle of a triangle divides the opposite side internally in the ratio of the sides containing the angle.

- In a triangle ABC, if D is a point on BC such that D divides BC in the ratio AB : AC, then AD is the bisector of ∠A.

- The external bisector of an angle of a triangle divides the opposite sides externally in the ratio of the sides containing the angle.

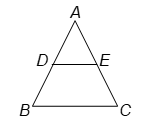

- The line drawn from the mid-point of one side of a triangle parallel to another side bisects the third side.

- The line joining the mid-points of two sides of a triangle is parallel to the third side.

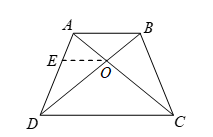

- The diagonals of a trapezium divide each other proportionally.

- If the diagonals of a quadrilateral divide each other proportionally, then it is a trapezium.

- Any line parallel to the parallel sides of a trapezium divides the non-parallel sides proportionally.

- If three or more parallel lines are intersected by two transversal, then the intercepts made by them on the transversal are proportional.

SOLVED PROBLEMS

Problem 1:

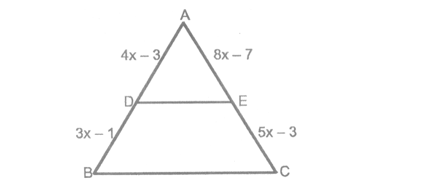

Question: In a ∠ABC, D and E are points on the sides AB and AC respectively such that DE || BC. If AD = 4x – 3, AE = 8x – 7, BD = 3x – 1 and CE = 5x – 3, find the value of x.

Solution:

In ∠ABC, we have

DE||BC.

AD/BD = AE/CE. [By Basic Proportionality Theorem]

(4x - 3)/(3x - 1) = (8x - 7)/(5x - 3)

(4x – 3)(5x – 3) = (8x – 7)(3x – 1)

20x² – 15x – 12x + 9 = 24x² – 21x – 8x + 7

20x² – 27x + 9 = 24x² – 29x + 7

4x² – 2x – 2 = 0

2x² – x – 1 = 0

(2x + 1)(x – 1) = 0

x = 1 or x = –1/2.

So, the required value of x is 1.

[x = -1/2 is neglected as length cannot be negative].

Problem 2:

Question: D and E are respectively the points on the sides AB and AC of a ∠ABC such that AB = 12 cm, AD = 8 cm, AE = 12 cm and AC = 18 cm, show that DE || BC.

Solution:

We have,

AB = 12 cm, AC = 18 cm, AD = 8 cm and AE = 12 cm.

BD = AB - AD = (12 – 8) cm = 4 cm.

CE = AC – AE = (18 – 12) cm = 6 cm.

Now, AD/BD = 8/4 = 2.

And, AE/CE = 12/6 = 2

AD/BD = AE/CE.

Thus, DE divides sides AB and AC of ∠ABC in the same ratio. Therefore, by the converse of basic proportionality theorem we have DE||BC.

Problem 3:

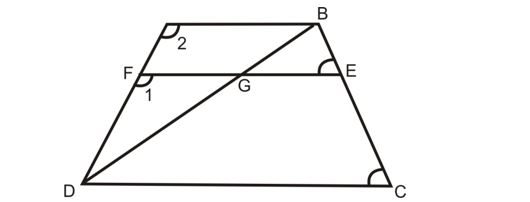

Question: In a trapezium ABCD AB||DC and DC = 2AB. EF drawn parallel to AB cuts AD in F and BC in E such that BE/EC = 4/3. Diagonal DB intersects EF at G. Prove that 7FE = 10AB.

Solution:

In ∠DFG and ∠DAB,

∠1 = ∠2 [Corresponding ∠s ∵ AB || FG]

∠FDG = ∠ADB [Common]

∠DFG ~ ∠DAB [By AA rule of similarity]

FG/AB = DF/DA .....(i)

Again in trapezium ABCD

EF||AB||DC

BE/EC = AF/FD

4/3 = AF/FD

FD/AF = 3/4

(FD + AF)/AF = (3 + 4)/4

DA/AF = 7/4

AF/DA = 4/7

DF/DA = (DA - AF)/DA = 1 - 4/7 = 3/7 …….(ii)

From (i) and (ii), we get

FG/AB = 3/7 i.e. FG = (3/7)AB ......(iii)

In ∠BEG and ∠BCD, we have

∠BEG = ∠BCD [Corresponding angle ∵ EG||CD]

∠GBE = ∠DBC [Common]

∠BEG ~ ∠BCD [By AA rule of similarity]

EG/CD = BE/BC

EG/CD = BE/(BE + EC)

EG/CD = 4/(4 + 3) = 4/7

EG = (4/7)CD = (4/7) × 2AB = (8/7)AB .....(iv)

Adding (iii) and (iv), we get

FG + EG = (3/7)AB + (8/7)AB

FE = (11/7)AB

7FE = 10AB. Hence proved.

Problem 4:

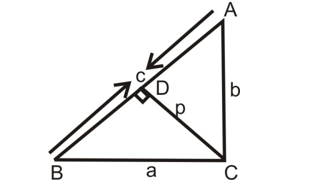

Question: In ∠ABC, if AD is the bisector of ∠A, prove that AB/AC = BD/DC.

Solution:

In ∠ABC, AD is the bisector of ∠A.

BD/DC = AB/AC ....(i) [By internal bisector theorem]

From A draw AL ⊥ BC

AB/AC = BD/DC. [From (i)] Hence Proved.

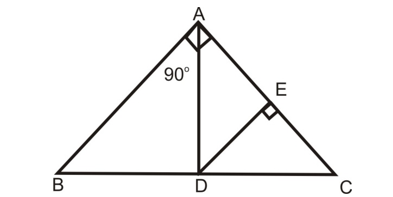

Problem 5:

Question: ∠BAC = 90°, AD is its bisector. If DE ⊥ AC, prove that DE × (AB + AC) = AB × AC.

Solution:

It is given that AD is the bisector of ∠A of ∠ABC.

BD/DC = AB/AC

(BD + DC)/DC = (AB + AC)/AC [Adding 1 on both sides]

BC/DC = (AB + AC)/AC

DC/BC = AC/(AB + AC). ...(i)

In ∠'s CDE and CBA, we have

∠DCE = ∠BCA [Common]

∠DEC = ∠BAC. [Each equal to 90°]

So by AA-criterion of similarity

∠CDE ~ ∠CBA

DE/AB = DC/BC ...(ii)

From (i) and (ii), we have

DE/AB = AC/(AB + AC)

DE × (AB + AC) = AB × AC.

Problem 6:

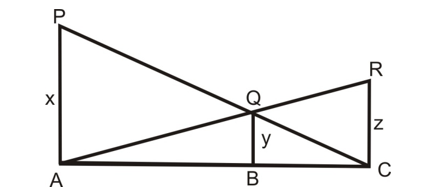

Question: In the given figure, PA, QB and RC are each perpendicular to AC. Prove that 1/x + 1/z = 1/y.

Solution:

In ∠PAC, we have BQ||AP

∠CBQ ~ ∠CAP

BQ/AP = BC/AC

y/x = (AC - AB)/AC = 1 - AB/AC. ...(i)

In ∠ACR, we have BQ||CR

∠ABQ ~ ∠ACR

BQ/CR = AB/AC

y/z = AB/AC. ...(ii)

Adding (i) and (ii), we get

y/x + y/z = 1 - AB/AC + AB/AC

y/x + y/z = 1

1/x + 1/z = 1/y. Hence Proved

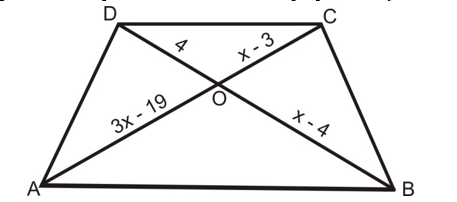

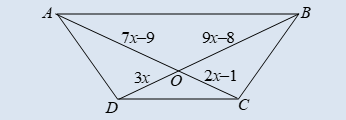

Problem 7:

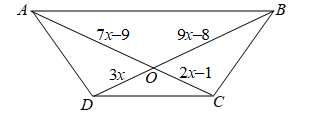

Question: In the given figure, AB||CD. Find the value of x.

Solution:

Since the diagonals of a trapezium divide each other proportionally.

(x - 3)/(x - 4) = (3x - 19)/(x - 4)

(x - 3)(x - 4) = (3x - 19)(x - 4)

12x – 76 = x² – 4x – 3x + 12

x² – 19x + 88 = 0

x² – 11x – 8x + 88 = 0

(x – 8)(x – 11) = 0

x = 8 or x = 11.

CRITERIA FOR SIMILARITY OF TWO TRIANGLES

Two triangles are said to be similar if (i) their corresponding angles are equal and (ii) their corresponding sides are in the same ratio (or proportional).

Thus, two triangles ABC and DEF are similar if

(i) ∠A = ∠D, ∠B = ∠E, ∠C = ∠F and

(ii) AB/DE = BC/EF = AC/DF.

In this section, we shall make use of the theorems discussed in earlier sections to derive some criteria for similar triangles which in turn will imply that either of the above two conditions can be used to define the similarity of two triangles.

AAA and SSS Similarity Theorems

CHARACTERISTIC PROPERTY 1 (AAA SIMILARITY)

THEOREM 3:

Statement: If in two triangles, the corresponding angles are equal, then the triangles are similar.

Given: Two triangles ABC and DEF in which ∠A = ∠D, ∠B = ∠E, ∠C = ∠F.

To prove: ∠ABC ~ ∠DEF.

Proof:

Case 1: When AB = DE

In triangles ABC and DEF, we have

∠A = ∠D [Given]

AB = DE [Given]

∠B = ∠E [Given]

∴ ∠ABC ≅ ∠DEF [By ASA congruency]

⇒ BC = EF and AC = DF [c.p.c.t.]

Thus AB/DE = BC/EF = AC/DF [corresponding sides of similar ∠s are proportional]

Hence ∠ABC ~ ∠DEF

Case 2: When AB < DE

Let P and Q be points on DE and DF respectively such that DP = AB and DQ = AC. Join PQ.

In ∠ABC and ∠DPQ, we have

AB = DP [By construction]

∠A = ∠D [Given]

AC = DQ [By construction]

∴ ∠ABC ≅ ∠DPQ [By SAS congruency]

∴ ∠ABC = ∠DPQ [c.p.c.t.] …(i)

But ∠ABC = ∠DEF [Given] …(ii)

∴ ∠DPQ = ∠DEF [c.p.c.t.]

But ∠DPQ and ∠DEF are corresponding angles.

⇒ PQ || EF

∴ DP/DE = DQ/DF [Corollary to BPT Theorem]

∴ AB/DE = AC/DF. [∵ DP = AB and DQ = AC (by construction)]

Similarly AB/DE = BC/EF.

∴ AB/DE = BC/EF = AC/DF.

Hence, ∠ABC ~ ∠DEF.

Case 3: When AB > DE

Let P and Q be points on AB and AC respectively such that AP = DE and AQ = DF. Join PQ.

In ∠APQ and ∠DEF, we have

AP = DE [By construction]

AQ = DF [By construction]

∠A = ∠D [Given]

∴ ∠APQ ≅ ∠DEF [By SAS congruency]

∴ ∠APQ = ∠DEF [c.p.c.t.] …(i)

But ∠DEF = ∠ABC. [Given] …(ii)

From (i) and (ii) we have

∴ ∠APQ = ∠ABC.

But ∠APQ and ∠ABC are corresponding angles

∴ PQ || BC

∴ AP/AB = AQ/AC [Corollary to BPT Theorem]

∴ DE/AB = DF/AC [∵ AP = DE and AQ = DF (by construction)]

Similarly DE/AB = EF/BC.

Thus DE/AB = EF/BC = DF/AC

Or, AB/DE = BC/EF = AC/DF.

Hence ∠ABC ~ ∠DEF.

CHARACTERISTIC PROPERTY 2 (SSS SIMILARITY)

THEOREM 4:

Statement: If the corresponding sides of two triangles are proportional, then they are similar.

Given: Two triangles ABC and DEF such that

AB/DE = BC/EF = CA/FD

To prove: ∠ABC ~ ∠DEF

Construction: Let P and Q be points on DE and DF respectively such that DP = AB and DQ = AC. Join PQ

Proof:

AB/DE = AC/DF [Given]

⇒ DP/DE = DQ/DF …(i)

[∵ DP = AB and DQ = AC (by construction)].

In ∠DEF, we have

DP/DE = DQ/DF [From (i)]

∴ PQ || EF [By the converse of BPT]

∴ ∠DPQ = ∠DEF and ∠DQP = ∠DFE [Corresponding angles]

∴ ∠DPQ ~ ∠DEF [By AA similarity] …(ii)

∴ DP/DE = PQ/EF

or AB/DE = PQ/EF [∵ DP = AB] …(iii)

But AB/DE = BC/EF [given] …(iv)

From equations (iii) and (iv), we have

PQ/EF = BC/EF

⇒ BC = PQ …(v)

In ∠ABC and ∠DPQ, we have

AB = DP [By construction]

AC = DQ [By construction]

BC = PQ [By (v)]

∴ ∠ABC ≅ ∠DPQ [by SSS congruency]

⇒ ∠ABC ~ ∠DPQ. [∵ ∠ABC ≅ ∠DPQ ⇔ ∠ABC ~ ∠DPQ] ... (vi)

From equation (ii) and (vi), we get

∠ABC ~ ∠DEF.

CHARACTERISTIC PROPERTY 3 (SAS SIMILARITY)

THEOREM 5:

Statement: If one angle of a triangle is equal to one angle of the other and the sides including these angles are proportional than the two triangles are similar.

Given: Two triangle ABC and DEF such that ∠A = ∠D and AB/DE = AC/DF.

To prove: ∠ABC ~ ∠DEF.

Construction: Let P and Q be points on DE and DF respectively such that DP = AB and DQ = AC. Join PQ.

Proof:

In ∠ABC and ∠DPQ, we have

AB = DP [By construction]

AC = DQ [By construction]

∠A = ∠D [Given]

∠ABC ≅ ∠DPQ [By SAS congruency] …(i)

Now, AB/DE = AC/DF …(ii)

DP/DE = DQ/DF. [∵ AB = DP and AC = DQ (by construction)]

In ∠DEF, we have

DP/DE = DQ/DF. [From (ii)]

PQ || EF [By the converse of BPT]

∠DPQ = ∠DEF and ∠DQP = ∠DFE [Corresponding angles]

∠DPQ ~ ∠DEF [By AA similarity] …(iii)

From equations (i) and (iii), we get ∠ABC ~ ∠DEF.

SOLVED PROBLEMS

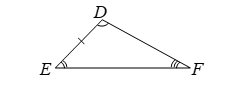

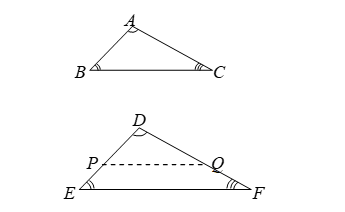

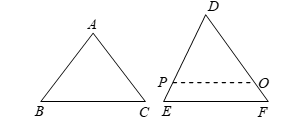

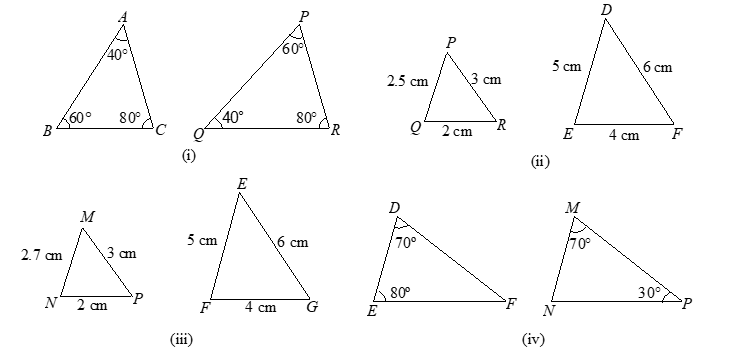

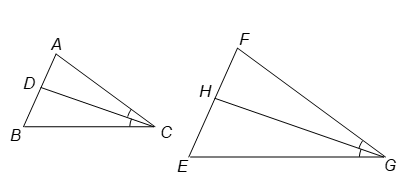

Problem 1:

Question: Examine each pair of triangles in figure and state which pair of triangles are similar. Also, state the similarity criterion used and write the similarity relation in symbolic form.

Solution:

(i) In triangles ABC and PQR, we observe that

∠A = ∠Q = 40°, ∠B = ∠P = 60° and ∠C = ∠R = 80°

Therefore, by AAA-criterion of similarity

∠BAC ~ ∠PQR.

(ii) In triangle PQR and DEF, we observe that

PQ/DE = QR/EF = PR/DF = 2/1 = 2.

Therefore, by SSS-criterion of similarity, we have

∠PQR ~ ∠DEF

(iii) In ∠'s MNP and EFG, we observe that

MN/EF = 2.5/5 = 1/2, NP/FG = 5/10 = 1/2, MP/EG = 6/8 = 3/4.

Therefore, these two triangles are not similar as they do not fulfill SSS-criterion of similarity.

(iv) In ∠'s DEF and MNP, we have

∠D = ∠M = 70°

∠E = ∠N = 80°. [∵ ∠N = 180° – ∠M – ∠P = 180° – 70° – 30° = 80°]

So by AA-criterion of similarity ∠DEF ~ ∠MNP.

Problem 2:

Question: Prove that the ratio of the perimeters of two similar triangles is the same as the ratio of their corresponding sides.

Solution:

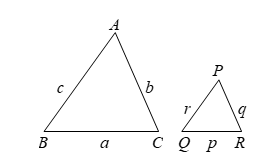

Given: ∠ABC and ∠PQR in which

BC = a, CA = b, AB = c and QR = p, RP = q, PQ = r.

Also ∠ABC ~ ∠PQR.

To Prove: (a + b + c)/(p + q + r) = a/p = b/q = c/r.

Proof:

Since ∠ABC and ∠PQR are similar, therefore their corresponding sides are proportional.

Let a/p = b/q = c/r = k …(i)

a = kp, b = kq and c = kr

(a + b + c)/(p + q + r) = (kp + kq + kr)/(p + q + r)

= k(p + q + r)/(p + q + r) = k. ... (ii)

From (i) and (ii), we get

(a + b + c)/(p + q + r) = a/p = b/q = c/r. [each equal to k]

Problem 3:

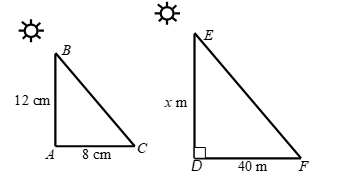

Question: A vertical stick 12m long casts a shadow 8m long on the ground. At the same time a tower casts the shadow 40m long on the ground. Determine the height of the tower.

Solution:

Let AB be the vertical stick and AC be its shadow. Also, let DE be the vertical tower and DF be its shadow. Join BC and EF.

Let DE = x metres.

We have,

AB = 12m, AC = 8m, and DF = 40m.

In ∠ABC and ∠DEF, we have

∠A = ∠D = 90° and ∠C = ∠F. [Angle of elevation of the sun]

Therefore, by AA-criterion of similarity

∠ABC ~ ∠DEF

AB/DE = AC/DF

12/x = 8/40

x = (12 × 40)/8 = 60 metres.

Problem 4:

Question: In the given figure, E is a point on side CB produced of an isosceles triangle ABC with AB = AC. If AD ⊥ BC and EF ⊥ AC, prove that ∠ABD ~ ∠ECF.

Solution:

Given: An isosceles ∠ABC in which AB = AC, E is a point on CB produced, AD ⊥ BC and EF ⊥ AC.

To prove: ∠ABD ~ ∠ECF.

Proof:

In ∠ABC, since AB = AC, therefore ∠C = ∠B [∠s opposite to equal sides are equal]

In ∠ABD and ∠ECF

∠B = ∠C [Proved above]

and ∠EFC = ∠ADB [each 90°]

∠ABD ~ ∠ECF. [AA similarity]

Problem 5:

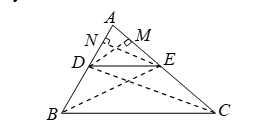

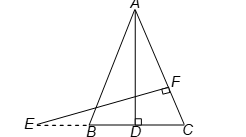

Question: In figure, if ∠ABE ≅ ∠ACD, prove that ∠ADE ~ ∠ABC.

Solution:

Given: ∠ABE ≅ ∠ACD.

To prove: ∠ADE ~ ∠ABC.

Proof:

Since ∠ABE ≅ ∠ACD

AB = AC [cpct] .... (i)

and, AD = AE .... (ii)

Also, AB/AC = AD/AE [From (i) and (ii)]

AB/AC = AD/AE = 1. … (iii)

Thus, in triangles ADE and ABC, we have

AD/AB = AE/AC and, ∠BAC = ∠DAE. [Common]

Hence, by SAS criterion of similarity.

∠ADE ~ ∠ABC.

Problem 6:

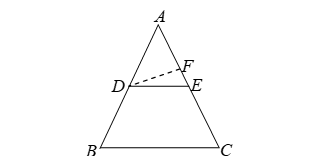

Question: In figure, if BD ⊥ AC and CE ⊥ AB, prove that

(i) ∠AEC ~ ∠ADB.

(ii) CA/AB = CE/DB.

Solution:

Given: BD ⊥ AC and CE ⊥ AB.

To prove: (i) ∠AEC ~ ∠ADB. (ii) CA/AB = CE/DB.

Proof:

(i) In ∠'s AEC and ADB, we have ∠AEC = ∠ADB = 90° [∵ CE ⊥ AB and BD ⊥ AC]

and, ∠EAC = ∠DAB [Each equal to ∠A]

∠AEC ~ ∠ADB. [By AA similarity]

(ii) We have,

∠AEC ~ ∠ADB [Proved above]

CA/AB = CE/DB

CA/AB = CE/DB.

Problem 7:

Question: If CD and GH (D and H lie on AB and FE) are respectively bisectors of ∠ACB and ∠EGF and ∠ABC ~ ∠FEG, prove that

(i) CD/AC = GH/FG.

(ii) ∠DCB ~ ∠HGE.

Solution:

Given:

(i) ∠ABC ~ ∠FEG.

(ii) CD, the bisector of ∠ACB meets AB at D and

(iii) GH, the bisector of ∠EGF meets FE at H.

To prove: (i) CD/AC = GH/FG. (ii) ∠DCB ~ ∠HGE.

Proof:

(i) ∠ABC ~ ∠FEG [Given]

∠BAC = ∠EFG …(i)

∠ABC = ∠FEG …(ii)

and ∠ACB = ∠FGE …(iii)

[Corresponding angles of similar triangles]

(1/2)∠ACB = (1/2)∠FGE.

∠ACD = ∠FGH. …(iv)

[As CD is the bisector of ∠ACB]

and ∠DCB = ∠HGE. …(v)

[As GH is the bisector of ∠EGF]

In ∠ACD and ∠FGH, we have

∠DAC = ∠HFG [From (i)]

∠ACD = ∠FGH [From (iv)]

∠ACD ~ ∠FGH [By AA similarity]

CD/AC = GH/FG.

(ii) In ∠DCB and ∠HGE, we have

∠DBC = ∠HEG [From (ii)]

∠DCB = ∠HGE [From (v)]

∠DCB ~ ∠HGE. [By AA similarity]

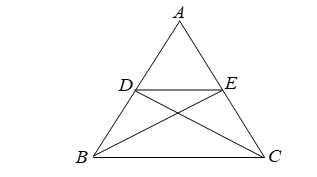

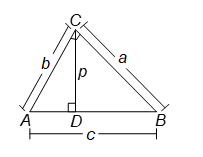

AREAS OF SIMILAR TRIANGLES

STATEMENT:

The ratio of the areas of two similar triangles is equal to the square of the ratio of their corresponding sides.

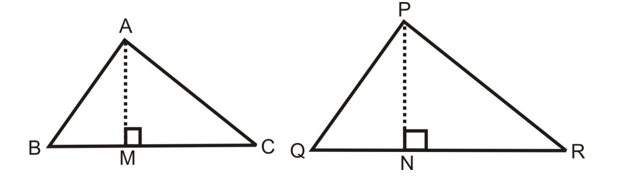

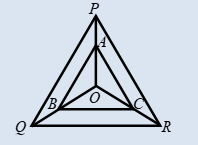

Given: Two triangles ABC and PQR such that ∠ABC ~ ∠PQR [Shown in the figure]

To Prove: ar(ABC)/ar(PQR) = AB²/PQ² = BC²/QR² = AC²/PR².

Construction: Draw altitudes AM and PN of the triangle ABC an PQR.

Proof:

ar(ABC) = (1/2) BC × AM.

And ar(PQR) = (1/2) QR × PN.

So, ar(ABC)/ar(PQR) = (BC × AM)/(QR × PN) = (BC/QR) × (AM/PN) ....(i)

Now, in ∠ABM and ∠PQN,

And ∠B = ∠Q [As ∠ABC ~ ∠PQR]

∠M = ∠N. [90° each]

So, ∠ABM ~ ∠PQN. [AA similarity criterion]

Therefore, AM/PN = AB/PQ ....(ii)

Also, ∠ABC ~ ∠PQR. [Given]

So, AB/PQ = BC/QR = AC/PR. .....(iii)

Therefore, ar(ABC)/ar(PQR) = (BC/QR) × (AM/PN) [From (i) and (ii)]

= (BC/QR) × (AB/PQ) [From (iii)]

= (AB/PQ) × (AB/PQ) = AB²/PQ².

Now using (iii), we get

ar(ABC)/ar(PQR) = AB²/PQ² = BC²/QR² = AC²/PR²

PROPERTIES OF AREAS OF SIMILAR TRIANGLES:

- The areas of two similar triangles are in the ratio of the squares of corresponding altitudes.

- The areas of two similar triangles are in the ratio of the squares of the corresponding medians.

- The area of two similar triangles are in the ratio of the squares of the corresponding angle bisector segments.

SOLVED PROBLEMS ON AREAS

Problem 1:

Question: Prove that the area of the equilateral triangle described on the side of a square is half the area of the equilateral triangle described on this diagonals.

Solution:

Given: A square ABCD. Equilateral triangles BCE and ACF have been described on side BC and diagonals AC respectively.

To prove: Area (BCE) = (1/2) Area (ACF).

Proof:

Since ∠BCE and ∠ACF are equilateral. Therefore, they are equiangular (each angle being equal to 60°) and hence ∠BCE ~ ∠ACF.

ar(BCE)/ar(ACF) = BC²/AC²

= BC²/(√2 BC)² [∵ AC = √2 BC]

= BC²/(2BC²) = 1/2

ar(BCE) = (1/2) ar(ACF).

Problem 2:

Question: The areas of two similar triangles ABC and PQR are 64 cm² and 36 cm² respectively. If QR = 16.5 cm, find BC.

Solution:

Since the ratio of the areas of two similar triangles is equal to the ratio of the squares of the corresponding sides.

ar(ABC)/ar(PQR) = BC²/QR²

64/36 = BC²/(16.5)²

BC²/272.25 = 16/9

BC² = (16 × 272.25)/9 = 484

BC = √484 = 22

Hence BC = 22 cm.

Problem 3:

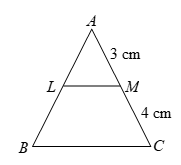

Question: In the given figure, LM || BC. AM = 3 cm, MC = 4 cm.

If the ar(ALM) = 27 cm², calculate the ar(ABC).

Solution:

Given: LM || BC AM = 3 cm, MC = 4 cm and ar(ALM) = 27 cm²

To Find: ar(ABC).

Proof:

∠ALM = ∠ABC and ∠AML = ∠ACB [Corresponding ∠s]

∠ALM ~ ∠ABC [By AA criterion of similarity]

Since the ratio of the areas of two similar triangles is equal to the ratio of the squares of any two corresponding sides.

Therefore,

ar(ALM)/ar(ABC) = AM²/AC²

27/ar(ABC) = 3²/(3 + 4)²

27/ar(ABC) = 9/49

ar(ABC) = (27 × 49)/9

ar(ABC) = 3 × 49

ar (ABC) = 147 cm².

Problem 4:

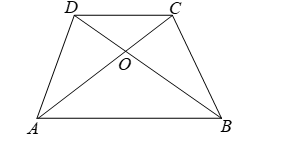

Question: In the given figure, ABCD is a trapezium in which AB || DC and AB = 2 CD. Find the ratio of the areas of triangles AOB and COD.

Solution:

Given: ABCD is a trapezium in which AB || DC and AB = 2 CD.

To Find: Ratio of the areas of triangles AOB and COD.

Proof:

In ∠AOB and ∠COD,

∠AOB = ∠COD [Vertically opposite angles]

∠OAB = ∠OCD [Alternate angles as AB || DC]

∠AOB ~ ∠COD. [By AA similarity]

Since the ratio of the areas of two similar triangles is equal to the ratio of squares of any two corresponding sides

ar(AOB)/ar(COD) = AB²/CD² [∵ AB = 2 CD]

= (2CD)²/CD² = 4CD²/CD² = 4/1.

Hence, ar(AOB) : ar(COD) = 4 : 1.

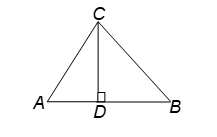

PYTHAGORAS THEOREM

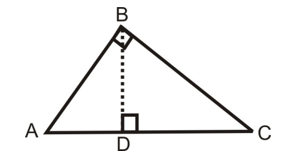

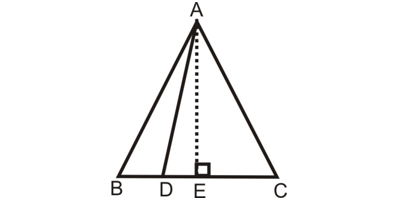

Statement:

In a right triangle, the square of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the square of the other two sides.

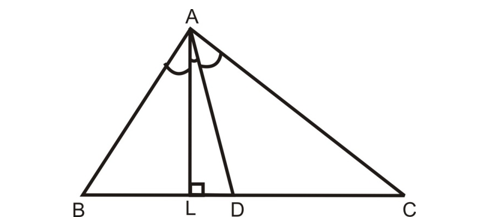

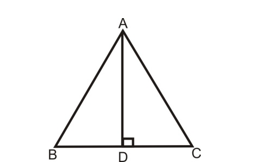

Given: A right triangle ABC, right angled at B.

To prove: AC² = AB² + BC².

Construction: Draw BD ⊥ AC.

Proof:

In ∠ADB and ∠ABC, we have

∠ADB = ∠ABC [Each equal to 90°]

∠A = ∠A [Common]

∠ADB ~ ∠ABC [By AA similarity]

AD/AB = AB/AC [Corresponding sides of similar triangles are proportional]

AB² = AC × AD …(i)

In ∠BCD and ∠ACB, we have

∠CDB = ∠CBA [Each equal to 90°]

∠C = ∠C. [Common]

By AA similarity criterion

∠BCD ~ ∠ACB

CD/BC = BC/AC

BC² = AC × CD …(ii)

Adding equations (i) and (ii), we get

AB² + BC² = AC × AD + AC × CD

AB² + BC² = AC(AD + CD)

AB² + BC² = AC × AC

Hence, AC² = AB² + BC². Hence Proved.

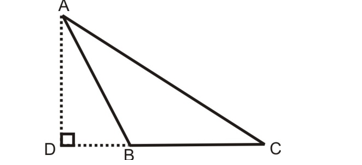

CONVERSE OF PYTHAGORAS THEOREM

Statement:

In a triangle, if the square of one side is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides, then the angle opposite to the first side is a right angle.

Given: A triangle ABC such that AC² = AB² + BC².

Construction: Construct a triangle DEF such that DE = AB, EF = BC and ∠E = 90°.

Proof:

In order to prove that ∠B = 90°, it is sufficient to show ∠ABC ≅ ∠DEF. For this we proceed as follows Since ∠DEF is a right – angled triangle with right angle at E. Therefore, by Pythagoras theorem, we have

DF² = DE² + EF²

DF² = AB² + BC² [∵ DE = AB and EF = BC (By construction)]

DF² = AC² [∵ AB² + BC² = AC² (Given)]

DF = AC .....(i)

Thus, in ∠ABC and ∠DEF, we have

AB = DE, BC = EF. [By construction]

And AC = DF [From equation (i)]

∠ABC ≅ ∠DEF [By SSS criteria of congruency]

∠B = ∠E = 90°.

Hence, ∠ABC is a right triangle, right angled at B.

SOME RESULTS DEDUCED FROM PYTHAGORAS THEOREM:

- In the given figure ABC is an obtuse triangle, obtuse angled at B. If AD ⊥ CD, then AC² = AB² + BC² + 2BC × BD.

2. In the given figure, if ∠B of ∠ABC is an acute angle and AD ⊥ BC, then AC² = AB² + BC² – 2BC × BD.

- In any triangle, the sum of the squares of any two sides is equal to twice the square of half of the third side together with twice the square of the median which bisects the third side.

- Three times the sum of the squares of the sides of a triangle is equal to four times the sum of the squares o the medians of the triangle.

SOLVED PROBLEMS

Problem 1:

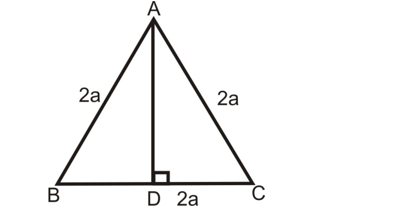

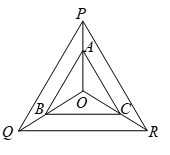

Question: In a ∠ABC, AB = BC = CA = 2a and AD ⊥ BC. Prove that

(i) AD = a√3.

(ii) area (∠ABC) = a²√3.

Solution:

(i) Here, AD ⊥ BC.

Clearly, ∠ABC is an equilateral triangle.

Thus, in ∠ABD and ∠ACD

AD = AD [Common]

∠ADB = ∠ADC. [90° each]

And AB = AC.

by RHS congruency condition

∠ABD ≅ ∠ACD

BD = DC = a.

Now, ∠ABD is a right angled triangle

AD = √(AB² - BD²) [Using Pythagoras Theorem]

AD = √((2a)² - a²)

AD = √(4a² - a²)

AD = √(3a²)

AD = a√3.

(ii) Area (∠ABC) = (1/2) × BC × AD

= (1/2) × 2a × a√3

= a²√3.

Problem 2:

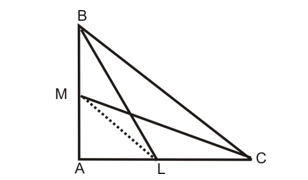

Question: BL and CM are medians of ∠ABC right angled at A. Prove that 4(BL² + CM²) = 5 BC².

Solution:

In ∠BAL

BL² = AL² + AB² ....(i) [Using Pythagoras theorem]

and In ∠CAM

CM² = AM² + AC² .....(ii) [Using Pythagoras theorem]

Adding (i) and (ii) and then multiplying by 4, we get

4(BL² + CM²) = 4(AL² + AB² + AM² + AC²)

= 4{AL² + AM² + (AB² + AC²)} [∵ ∠ABC is a right triangle]

= 4(AL² + AM² + BC²)

= 4(ML² + BC²) [∵ ∠LAM is a right triangle]

= 4ML² + 4 BC²

= 4(BC/2)² + 4BC²

[A line joining mid-points of two sides is parallel to third side and is equal to half of it, ML = BC/2]

= 4(BC²/4) + 4BC²

= BC² + 4BC² = 5BC². Hence proved.

Problem 3:

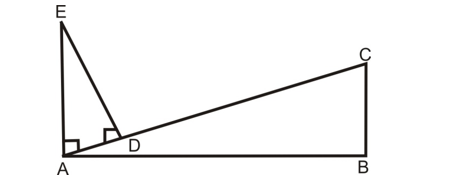

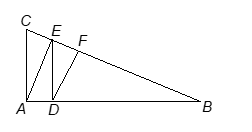

Question: In the given figure, BC ⊥ AB, AE ⊥ AB and DE ⊥ AC. Prove that DE × BC = AD × AB.

Solution:

In ∠ABC and ∠EDA,

We have

∠ABC = ∠ADE [Each equal to 90°]

∠ACB = ∠EAD [Alternate angles]

By AA Similarity

∠ABC ~ ∠EDA

BC/DE = AB/AD

DE × BC = AD × AB. Hence Proved.

Problem 4:

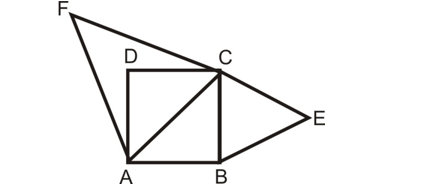

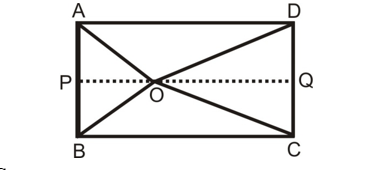

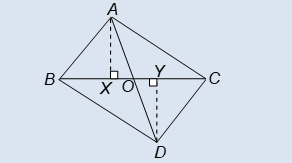

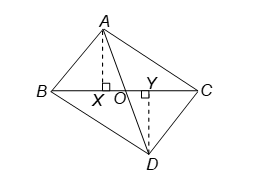

Question: O is any point inside a rectangle ABCD (shown in the figure). Prove that OB² + OD² = OA² + OC².

Solution:

Through O, draw PQ||BC so that P lies on AB and Q lies on DC.

Now PQ||BC

Therefore PQ ⊥ AB and PQ ⊥ DC [∵ ∠B = 90° and ∠C = 90°]

So, ∠BPQ = 90° and ∠CQP = 90°.

Therefore, BPQC and APQD are both rectangles.

Now, from ∠OPB,

OB² = BP² + OP² ....(i)

Similarly, from ∠ODQ,

OD² = OQ² + DQ² ....(ii)

From ∠OQC, we have

OC² = OQ² + CQ² ...(iii)

And form ∠OAP, we have

OA² = AP² + OP² ....(iv)

Adding (i) and (ii)

OB² + OD² = BP² + OP² + OQ² + DQ²

= CQ² + OP² + OQ² + AP²

[As BP = CQ and DQ = AP]

= CQ² + OQ² + OP² + AP²

= OC² + OA². [From (iii) and (iv)] Hence Proved.

Problem 5:

Question: ABC is a right triangle, right-angled at C. Let BC = a, CA = b, AB = c and let p be the length of perpendicular form C on AB, prove that

(i) cp = ab.

(ii) 1/p² = 1/a² + 1/b².

Solution:

Let CD ⊥ AB. Then CD = p

Area of ∠ABC = (1/2) (Base × height)

= (1/2) (AB × CD) = (1/2)cp.

Also,

area of ∠ABC = (1/2) (BC × AC) = (1/2) ab

(1/2) cp = (1/2) ab

cp = ab.

(ii) Since ∠ABC is a right triangle, right angled at C.

AB² = BC² + AC²

c² = a² + b²

1/c² = 1/(a² + b²)

1/c² = 1/(a² + b²)

(ab)²/c² = (ab)²/(a² + b²)

p² = (ab)²/(a² + b²) [∵ cp = ab ⇒ p = ab/c]

1/p² = (a² + b²)/(ab)²

1/p² = (a² + b²)/(a²b²)

1/p² = a²/(a²b²) + b²/(a²b²)

1/p² = 1/b² + 1/a².

Problem 6:

Question: In an equilateral triangle ABC, the side BC is trisected at D. Prove that 9 AD² = 7AB².

Solution:

ABC be an equilateral triangle and D be point on BC such that

BD = (1/3) BC. (Given)

Draw AE ⊥ BC, Join AD.

BE = EC (Altitude drawn from any vertex of an equilateral triangle bisects the opposite side)

So, BE = EC = BC/2.

In ∠ABC

AB² = AE² + EB² .....(i)

In ∠AED

AD² = AE² + ED² ....(ii)

From (i) and (ii)

AB² = AD² – ED² + EB²

AB² = AD² – (BE - BD)² + EB²

(BD + DE = BE ⇒ DE = BE - BD)

AB² = AD² – (BC/2 - BC/3)² + (BC/2)²

AB² = AD² – (3BC/6 - 2BC/6)² + BC²/4

AB² = AD² – (BC/6)² + BC²/4

AB² = AD² – BC²/36 + BC²/4

AB² = AD² – BC²/36 + 9BC²/36

AB² = AD² + 8BC²/36

AB² = AD² + 2BC²/9

AB² = AD² + 2AB²/9 [∵ BC = AB]

AB² - 2AB²/9 = AD²

(9AB² - 2AB²)/9 = AD²

7AB²/9 = AD²

9AD² = 7AB².

Practice Questions and Solutions

PRACTICE QUESTIONS - SET 1

Questions:

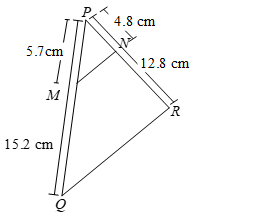

- M and N are points on the sides PQ and PR respectively of ∠PQR. State whether MN || QR. Given PQ = 15.2 cm, PR = 12.8 cm, PM = 5.7 cm, PN = 4.8 cm.

- In the following figure, if AB || DC, find the value of x.

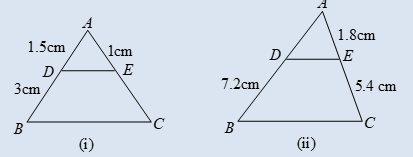

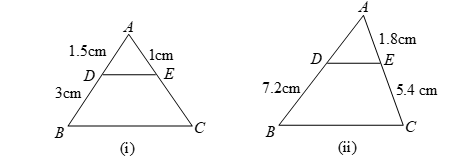

3. In the given figure (i) and (ii) DE || BC. Find EC in (i) and AD in (ii).

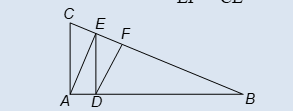

4. In the figure, if DE || AC and DF || AE, prove that BF/FE = BE/EC.

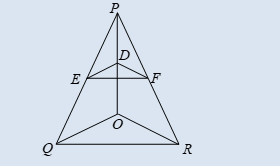

5. In the given figure, if DE || OQ and DF || OR, prove that EF || QR.

Answers:

- MN || QR, 2. x = 4, 3. (i) 2 cm, (ii) 2.4 cm

DETAILED SOLUTIONS - SET 1

Solution 1:

Question: M and N are points on the sides PQ and PR respectively of ∠PQR. State whether MN || QR. Given PQ = 15.2 cm, PR = 12.8 cm, PM = 5.7 cm, PN = 4.8 cm.

Solution:

It has been given that

PQ = 15.2 cm, PR = 12.8 cm,

PM = 5.7 cm and PN = 4.8 cm

∴ MQ = PQ – PM = (15.2 – 5.7) cm = 9.5 cm and

NR = PR – PN = (12.8 – 4.8) cm = 8 cm.

Now PM/MQ = 5.7/9.5 = 57/95 = 3/5 and PN/NR = 4.8/8 = 48/80 = 3/5.

∴ PM/MQ = PN/NR.

Thus, in ∠PQR, MN divides the sides PQ and PR in the same ratio. Therefore, by the converse of the Basic Proportionality Theorem, we have MN || QR.

Solution 2:

Question: In the following figure, if AB || DC, find the value of x.

Solution:

Since the diagonals of a trapezium divide each other proportionally

(3x - 1)/(x - 3) = (5x - 3)/(x + 1)

(3x - 1)(x + 1) = (5x - 3)(x - 3)

3x² + 3x - x - 1 = 5x² - 15x - 3x + 9

3x² + 2x - 1 = 5x² - 18x + 9

2x² - 20x + 10 = 0

x² - 10x + 5 = 0

3x(x – 2) + 4 (x – 2) = 0

(x - 2)(3x + 4) = 0

Either x - 2 = 0 or 3x + 4 = 0

x = 2 or x = -4/3.

[x = -4/3 rejected, as it makes line-segments negative]

Thus, x = 4

Solution 3:

Question: In the given figure (i) and (ii) DE || BC. Find EC in (i) and AD in (ii).

Solution:

(i) In ∠ABC, DE || BC then by Basic Proportionality (BPT) Theorem, we have

AD/DB = AE/EC

1.8/5.4 = 1.2/EC

EC = (1.2 × 5.4)/1.8 = 3.6 cm.

(ii) Also in figure (ii), in ∠ABC, DE || BC then by B.P.T, we have

AD/DB = AE/EC

AD/3.6 = 3/4.5

AD = (3 × 3.6)/4.5 = 2.4 cm.

Solution 4:

Question: In the figure, if DE || AC and DF || AE, prove that BF/FE = BE/EC.

Solution:

In ∠ABC, DE || AC then by B.P.T., we have

BD/DA = BE/EC. …(i)

In ∠ABE, DF || AE then by B.P.T., we have

BD/DA = BF/FE. …(ii)

From (i) and (ii), we get

BF/FE = BE/EC.

Solution 5:

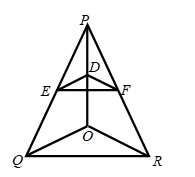

Question: In the given figure, if DE || OQ and DF || OR, prove that EF || QR.

Solution:

In ∠POQ, DE || OQ, then by BPT Theorem, we have

PD/DO = PE/EQ …(i)

Also, in ∠POR, DF || OR, then by BPT Theorem, we have

PD/DO = PF/FR. …(ii)

From equations, (i) and (ii),

PE/EQ = PF/FR.

∴ EF || QR [converse of BPT Theorem]

PRACTICE QUESTIONS - SET 2

Questions:

6. In figure, PQ || AB and PR || AC, prove that QR || BC.

7. Using Basic proportionality theorem, prove that the line drawn through the mid-point of one side of a triangle parallel to another side bisects the third side.

8. ABCD is a trapezium such that AB || DC. The diagonals AC and BD intersect at O. Prove that AO/OC = BO/OD or AO/BO = CO/DO.

9. In figure, prove that AB/AO = CD/OD.

10. Two isosceles triangles have equal vertical angles and their area are in the ratio 16 : 25. Find the ratio of their corresponding heights.

DETAILED SOLUTIONS - SET 2

Solution 6:

Question: In figure, PQ || AB and PR || AC, prove that QR || BC.

Solution:

In ∠POQ, PQ || AB, then by B.P.T., we have

OQ/QA = OP/PB. …(i)

Also in ∠POR, AC || PR, we have

OR/RC = OP/PB. …(ii)

From (i) and (ii), we get

OQ/QA = OR/RC.

∴ QR || BC [by converse of B.P.T.]

Solution 7:

Question: Using Basic proportionality theorem, prove that the line drawn through the mid-point of one side of a triangle parallel to another side bisects the third side.

Solution:

Given: A ∠ABC in which D is the mid-point of AB and DE || BC meeting AC at E.

To prove: AE = CE.

Proof:

In ∠ABC, DE || BC

AD/BD = AE/CE. [BPT Theorem]

But AD = BD [D is the mid-point of AB]

∴ AE/CE = 1 ⇒ AE = CE.

Hence, E is the midpoint of AC.

Solution 8:

Question: ABCD is a trapezium such that AB || DC. The diagonals AC and BD intersect at O. Prove that AO/OC = BO/OD or AO/BO = CO/DO.

Solution:

Given: ABCD is a trapezium such that AB || DC.

To prove: AO/OC = BO/OD or AO/BO = CO/DO.

Construction: Through O draw OE || CD.

Proof:

AB || DC [given]

and EO || DC [const.]

∴ EO || AB.

(∵ Two lines parallel to same line are parallel to each other)

Now, in ∠ABD, EO || AB, then by BPT Theorem we have

DO/OB = DE/EA …(i)

Also in ∠ADC, EO || DC, by BPT Theorem, we have

AO/OC = AE/ED …(ii)

From (i) and (ii), we get

AO/OC = BO/OD or AO/BO = CO/DO.

Solution 9:

Question: In figure, prove that AB/AO = CD/OD.

Solution:

Construction: Draw AX and DY ⊥ BC.

Proof:

In ∠AOX and ∠DOY, we have

∠AXO = ∠DYO [Both 90°]

∠AOX = ∠DOY [Vert. Opp. angles]

∠AOX ~ ∠DOY [By AA similarity]

∴ AO/OD = AX/DY …(i)

Now ar(∠AOB)/ar(∠DOC) = (1/2 × AB × AX)/(1/2 × CD × DY) = (AB × AX)/(CD × DY).

Thus ar(∠AOB)/ar(∠DOC) = (AB/CD) × (AX/DY) = (AB/CD) × (AO/OD). [Using (i)]

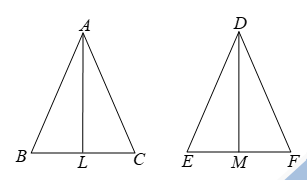

Solution 10:

Question: Two isosceles triangles have equal vertical angles and their area are in the ratio 16 : 25. Find the ratio of their corresponding heights.

Solution:

Given: Let ∠ABC and ∠DEF be the given triangles such that AB = AC and DE = DF, ∠A = ∠D

and, ar(∠ABC)/ar(∠DEF) = 16/25 …(i)

To Find: AL/DM

Construction: Draw AL ⊥ BC and DM ⊥ EF.

Proof:

Now, AB = AC, DE = DF

∴ AB/AC = 1 and DE/DF = 1

∴ AB/AC = DE/DF

Thus, in triangles ABC and DEF, we have

AB/DE = AC/DF and ∠A = ∠D. [Given]

So by SAS-similarity criterion, we have

∠ABC ~ ∠DEF

∴ ar(∠ABC)/ar(∠DEF) = AL²/DM²

[Ratio of areas of two similar triangles is equal to ratio of squares of their corresponding altitudes]

16/25 = AL²/DM² [Using (i)]

∴ AL/DM = 4/5.

PRACTICE QUESTIONS - SET 3

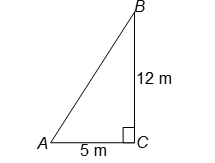

11. A ladder is placed in such a way that its foot is at a distance of 5 m from a wall and its top reaches a window 12 m above the ground. Determine the length of the ladder.

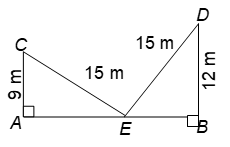

12. A ladder 15 m long reaches a window which is 9 m above the ground on one side of a street. Keeping its foot at the same point, the ladder is turned to the other side of the street to reach a window 12 m high. Find the width of the street.

13. In the given figure, ∠ACB = 90° and CD ⊥ AB. Prove that BC²/AC² = BD/AD.

14. ABC is a triangle right-angled at C and p is the length of the perpendicular from C to AB. Show that (a) pc = ab. (b) 1/p² = 1/a² + 1/b² where a = BC, b = AC and c = AB.

15. In ∠ABC, ∠C > 90° and side AC is produced to D such that segment BD is perpendicular to segment AD. Prove that AB² = AC² + BC² + 2AC.CD

DETAILED SOLUTIONS - SET 3

Question: A ladder is placed in such a way that its foot is at a distance of 5 m from a wall and its top reaches a window 12 m above the ground. Determine the length of the ladder.

Solution:

Let AB be the ladder, B be the window and BC be the wall.

Then BC = 12 m, AC = 5m and ∠ACB = 90°.

In right triangle ACB, we have

AB² = BC² + AC² [By Pythagoras Theorem]

AB² = (12)² + (5)²

AB² = 144 + 25 = 169

AB = √169 = 13 m.

Hence the length of the ladder is 13 m.

Question: A ladder 15 m long reaches a window which is 9 m above the ground on one side of a street. Keeping its foot at the same point, the ladder is turned to the other side of the street to reach a window 12 m high. Find the width of the street.

Solution:

Let AB be the street and let C and D be the windows at heights of 9 m and 12 m respectively from the ground.

Let E be the foot of the ladder. Then EC and ED are the two positions of the ladder.

Clearly AC = 9 m, BD = 12 m, EC = ED = 15 m and ∠CAE = ∠DBE = 90°

In right triangle CAE, we have

EC² = AC² + AE² [By Pythagoras Theorem]

(15)² = (9)² + AE²

AE² = (15)² – (9)² = (225 – 81) = 144

AE = 12 m. …(i)

In right triangle DBE, we have

ED² = BD² + EB² [By Pythagoras Theorem]

(15)² = (12)² + EB²

EB² = (15)² – (12)² = (225 – 144) = 81

EB = 9 m …(ii)

Adding equations (i) and (ii), we get

AE + EB = (12 + 9) m ⇒ AB = 21 m

Hence, the width of the street is 21 m.

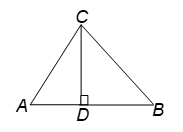

Question: In the given figure, ∠ACB = 90° and CD ⊥ AB. Prove that BC²/AC² = BD/AD.

Solution:

Given: ∠ACB = 90° and CD ⊥ AB.

To prove: BC²/AC² = BD/AD.

Proof:

In ∠ACD and ∠ABC

∠A = ∠A [Common]

∠ADC = ∠ACB [Both 90°]

∠ACD ~ ∠ABC [By AA similarity]

So AC/AB = AD/AC

or, AC² = AB × AD. …(i)

Similarly, ∠BCD ~ ∠BAC.

So BC/AB = BD/BC

or, BC² = AB × BD. …(ii)

Therefore, from (i) and (ii),

BC²/AC² = (AB × BD)/(AB × AD) = BD/AD.

Question: ABC is a triangle right-angled at C and p is the length of the perpendicular from C to AB. Show that (a) pc = ab. (b) 1/p² = 1/a² + 1/b² where a = BC, b = AC and c = AB.

Solution:

(a) Taking c as the base and p as the altitude, we have

area of ∠ABC = (1/2) × c × p …(i)

Taking b as the base and a as the altitude, we have

area ∠ABC = (1/2) × a × b …(ii)

∴ (1/2) × c × p = (1/2) × a × b [From (i) and (ii)]

⇒ pc = ab Hence Proved.

(b) ∠ABC is a right triangle-angled at C.

∴ c² = a² + b² …(iii)

[By Pythagoras Theorem]

pc = ab [proved above]

or p = ab/c

∴ p² = (ab)²/c² [From equation (iii)]

p² = (ab)²/(a² + b²)

1/p² = (a² + b²)/(ab)²

1/p² = (a² + b²)/(a²b²)

1/p² = a²/(a²b²) + b²/(a²b²)

1/p² = 1/b² + 1/a².