In-Depth Class 10 Real Numbers Notes for Exam Success

Class 10 Real Numbers Notes provide a strong foundation in mathematics, covering essential topics like divisibility, HCF, LCM, prime factorization, and Euclid’s lemma. These notes are designed to help students grasp fundamental concepts with clear explanations and solved examples. Understanding real numbers is crucial for solving complex algebraic problems and for laying the groundwork for higher mathematics. The notes include practice questions, step-by-step solutions, and shortcuts that make learning easier and more effective. Whether it is calculating HCF and LCM of large numbers or exploring the properties of rational and irrational numbers, these notes ensure students are well-prepared for exams. Go through the NCERT textbook and solve the NCERT questions with the help of the NCERT Solutions for class 10 Maths. With these Real Numbers Notes, students can quickly revise concepts, improve problem-solving speed, and gain confidence. These notes are suitable for students preparing for Class 10 board exams, competitive tests, or anyone looking to strengthen their number theory skills.

What Are Real Numbers?

Real numbers comprise the complete set of rational and irrational numbers combined. A rational number can be expressed as p/q where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0, while an irrational number cannot be expressed in this form. This comprehensive number system forms the foundation of higher mathematics and appears extensively in competitive examinations like NTSE.

Every real number occupies a unique position on the number line, making them essential for measuring quantities, distances, and solving practical problems. The classification and properties of real numbers determine how we perform arithmetic operations and solve equations.

Classification of Numbers

Prime and Composite Numbers

A prime number has exactly two distinct factors: 1 and itself. The smallest prime number is 2, which is also the only even prime. Examples include 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, and 13. Understanding that 1 is neither prime nor composite is crucial—this special status stems from the requirement that primes must have exactly two different factors.

Composite numbers possess at least three factors. The smallest composite number is 4. Numbers like 6, 12, and 15 are composite because they can be divided evenly by numbers other than 1 and themselves.

Twin primes are pairs of prime numbers that differ by 2, such as (3, 5), (11, 13), and (17, 19). Co-prime numbers share no common factors except 1, meaning their highest common factor (HCF) equals 1. For instance, 12 and 35 are co-prime despite both being composite.

Even, Odd, and Consecutive Numbers

Even numbers are divisible by 2 and can be expressed as 2k for some integer k. Odd numbers cannot be divided evenly by 2 and take the form 2k + 1. Any integer sequence where each number differs from the next by 1 represents consecutive numbers, such as 50, 51, 52, 53.

Euclid's Division Lemma and Algorithm

The Division Lemma

For any two positive integers a and b, there exist unique integers q (quotient) and r (remainder) such that:

a = bq + r, where 0 ≤ r < b

This fundamental principle states that when dividing a by b, you obtain a quotient and a remainder smaller than the divisor. If b divides a evenly, then r = 0.

An important property: if a = bq + r, then every common divisor of a and b is also a common divisor of b and r. This property makes Euclid's algorithm efficient for finding the HCF of two numbers.

Finding HCF Using Euclid's Algorithm

To find the HCF of two numbers c and d where c > d:

- Apply the division lemma to find q and r such that c = dq + r (0 ≤ r < d)

- If r = 0, then d is the HCF

- If r ≠ 0, apply the division lemma to d and r

- Continue until the remainder becomes zero—the divisor at this stage is the HCF

For example, to find HCF(575, 15):

- 575 = 15 × 38 + 5

- 15 = 5 × 3 + 0

Since the remainder is 0, the HCF is 5.

The Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic

This theorem states that every composite number can be expressed as a product of prime numbers, and this factorization is unique except for the order of factors. This uniqueness principle is fundamental to number theory.

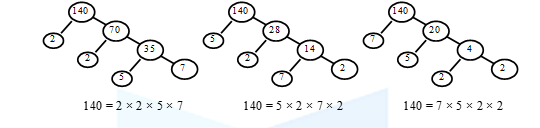

For instance, 140 can be factorized as:

- 140 = 2 × 2 × 5 × 7 = 2² × 5 × 7

Regardless of the factorization method used, the same prime factors with the same exponents appear.

Applications in Finding HCF and LCM

HCF (Highest Common Factor): Take each common prime factor with the smallest exponent appearing in all factorizations.

LCM (Least Common Multiple): Take all prime factors with the greatest exponent appearing in any factorization.

The relationship HCF(a, b) × LCM(a, b) = a × b holds for any two positive integers.

Decimal Representation of Rational Numbers

Terminating Decimals

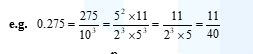

A rational number p/q (in lowest terms) has a terminating decimal expansion if and only if the prime factorization of q is of the form 2^m × 5^n, where m and n are non-negative integers.

Example: 13/3125 = 13/(2⁰ × 5⁵) has a terminating decimal expansion.

Non-Terminating Repeating Decimals

If the denominator q (in lowest terms) has prime factors other than 2 or 5, the rational number has a non-terminating repeating decimal expansion.

Example: 5/3 = 1.66666... (repeating)

Irrational Numbers

Irrational numbers cannot be expressed as p/q where p and q are integers. Their decimal expansions are non-terminating and non-repeating. Common examples include √2, √3, √5, π, and e.

Proving Irrationality

To prove √2 is irrational, assume it's rational: √2 = a/b (where a and b are co-prime). Squaring both sides gives 2 = a²/b², so a² = 2b². This means a² is even, hence a is even. Let a = 2c, then 4c² = 2b², so b² = 2c², making b even. But this contradicts our assumption that a and b are co-prime. Therefore, √2 is irrational.

Important property: If a is rational and b is irrational, then a + b and a × b (where a ≠ 0) are both irrational.

Divisibility Rules

Understanding divisibility rules accelerates problem-solving:

- Divisibility by 2: Last digit is even

- Divisibility by 3: Sum of digits is divisible by 3

- Divisibility by 4: Last two digits form a number divisible by 4

- Divisibility by 5: Last digit is 0 or 5

- Divisibility by 6: Number is divisible by both 2 and 3

- Divisibility by 9: Sum of digits is divisible by 9

- Divisibility by 11: Difference between sum of digits in odd positions and sum of digits in even positions is 0 or divisible by 11

For divisibility by 7: Double the units digit and subtract from the remaining number. If the result is divisible by 7, so is the original number.

Essential Formulas for Real Numbers

| Concept | Formula/Property | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Euclid's Division Lemma | a = bq + r, where 0 ≤ r < b | For integers a and b, unique quotient q and remainder r exist |

| HCF × LCM Relationship | HCF(a,b) × LCM(a,b) = a × b | Product of HCF and LCM equals product of the numbers |

| Terminating Decimal Condition | q = 2^m × 5^n | Rational p/q terminates if q has only factors 2 and 5 |

| Odd Integer Forms | 6q + 1, 6q + 3, 6q + 5 | Any odd positive integer takes one of these forms |

| Square Forms (mod 3) | 3m or 3m + 1 | Any perfect square is of form 3m or 3m + 1 |

| Cube Forms (mod 9) | 9m, 9m + 1, or 9m + 8 | Any perfect cube takes one of these three forms |

Practical Applications

Real numbers and their properties enable solving diverse problems:

- Finding optimal arrangements: Using HCF to determine maximum equal groups

- Meeting point problems: Using LCM to calculate when cyclic events coincide

- Prime factorization: Breaking down numbers for cryptography and computer science

- Decimal conversions: Understanding when fractions terminate or repeat

Mastery of real numbers provides the foundation for algebra, calculus, and advanced mathematics, making these concepts indispensable for academic success and competitive examinations.

Class 10 Real Numbers Notes & Questions with Solved Problems

The totality of rational numbers and irrational numbers is called the Real Numbers. That is, all numbers which are either rational or irrational are classified as real numbers. A real number which is not rational is called irrational.

Divisibility Relation

If a is divisible by b, we write as b | a ("b divides a").

- b is a factor of a (e.g. 2 is a factor of 10).

- b is a divisor of a (e.g. 3 is a divisor of 24 since 24 = 3 × 8).

- a is a multiple of b (e.g. 15 is a multiple of 5).

A non-zero integer a is said to divide another integer b if there exists an integer c such that b = a × c. Here, a is the divisor, c is the quotient, and b is the dividend.

Classification of Numbers

- Even Numbers: Natural numbers divisible by 2. Examples: 2, 4, 6, 8, ...

- Odd Numbers: Natural numbers not divisible by 2. Examples: 1, 3, 5, 7, ...

- Consecutive Numbers: Series of numbers each differing by one. Example: 50, 51, 52, 53.

Prime, Composite, Co-prime, Perfect & More

- Prime Number: A natural number with exactly two distinct positive divisors: 1 and itself (e.g. 2, 3, 5, 7,...).

- Composite Number: A natural number with at least three positive divisors (e.g. 4, 6, 12...).

- Twin-prime: Pair of primes differing by 2 (e.g. (3,5), (5,7)).

- Co-prime: Two numbers having no common factor other than 1 (e.g. 8, 15).

- Perfect Number: A number equal to the sum of its proper divisors (e.g. 6, 28).

Euclid's Division Lemma & Algorithm

Euclid's Division Lemma:

Given any two positive integers a and b, there exist unique integers q and r such that:

a = bq + r, with 0 ≤ r < b

Euclid's Division Algorithm:

Used to find the HCF (GCD) of two positive integers by repeated use of the Division Lemma.

Steps:

- Divide a by b, get quotient q and remainder r; a = bq + r,0 ≤ r < b.

- If r = 0, b is the HCF. Else, set a = b, b = r and repeat.

Example: HCF of 128 and 240:

240 = 128 × 1 + 112

128 = 112 × 1 + 16

112 = 16 × 7 + 0

HCF: 16

Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic

Every composite number can be expressed (factorized) as a product of prime numbers, and this factorization is unique (except for the order of factors).

- Practical Example of Prime Factorization

140 = 2 × 2 × 5 × 7

The order may differ, but the prime set remains unique.

Rational & Irrational Numbers

- Rational Number

A number of the form p/q, where p, q are integers and q ≠ 0.

Examples: 4 (=4/1), 1/3, 0.25 (=1/4), recurring decimals (0.333... = 1/3)

- Irrational Number

A number which is not rational, but can be represented on the number line.

Examples: √2, π, e.

Any non-terminating non-recurring decimal is irrational.

If x is rational and y is irrational, then x+y and x−y are irrational.

Divisibility Rules (2 to 11)

- By 2: Last digit even.

- By 3: Sum of digits is multiple of 3.

- By 4: Last two digits form a multiple of 4.

- By 5: Last digit 0 or 5.

- By 6: Divisible by 2 and 3.

- By 7: Double the last digit, subtract from rest; divisible by 7 means original number is too.

- By 8: Last three digits divisible by 8.

- By 9: Sum of digits multiple of 9.

- By 10: Last digit is 0.

- By 11: Difference of sums of alternate digits is 0 or multiple of 11.

[Insert diagram: Examples for divisibility by different numbers]

Decimal Representation of Rational Numbers

Theorem: Let x = p/q be a rational number in lowest terms.

- If q’s prime factorization is only of the form 2m × 5n, x has a terminating decimal expansion.

- Otherwise, x has a non-terminating, repeating decimal expansion.

Recurring decimals are rational; non-terminating, non-recurring decimals are irrational.

Worked Examples

- Show that any positive odd integer is of the form 6q+1, 6q+3, or 6q+5.

Solution: By division, an odd integer divided by 6 gives a remainder of 1, 3, or 5. - Use Euclid's division lemma to show cube of any positive integer is of the form 9m, 9m+1, or 9m+8.

- Show that only one among n, n+2, n+4 is divisible by 3 for any positive integer n.

Solution: By dividing n by 3 and checking remainders, only one of the numbers is divisible by 3 in each case.

Key Theorems

- If p is a prime number and p divides a², then p divides a.

- A rational number has a terminating decimal if the denominator has no prime factor other than 2 or 5.

- √2, √3, √5, ... are irrational numbers (with proof by contradiction).

Practice Exercises

- Check if 6n can ever end with the digit 0 for any natural number n.

Solution: No, as prime factorisation of 6n contains only 2s and 3s, never a 5. - An army contingent of 616 is to march behind a band of 32; find max columns.

Solution: HCF(616, 32) = 8 - Prove that √3 is irrational.

Solution: Suppose √3 = a/b. Then a²=3b²; both a, b divisible by 3, contradiction unless both zero. So, irrational.

Illustrative Problems

Find HCF of 825 and 175 by Euclid's algorithm:

825 = 175 × 4 + 125

175 = 125 × 1 + 50

125 = 50 × 2 + 25

50 = 25 × 2 + 0

HCF = 25

FUNDAMENTAL THEOREM OF ARITHMETIC

Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic

Every composite number can be expressed as a product of primes, and this factorization is unique, except for the order in which the prime factors occur.

Example: Prime Factorization of 140 in Different Orders

Some Important Results:

- Let 'p' be a prime number and 'a' be a positive integer. If 'p' divides a², then 'p' divides 'a'.

- Let x be a rational number whose decimal expansion terminates. Then, x can be expressed in the form p/q, where p and q are co-primes, and prime factorization of q is of the form 2m × 5n, where m, n are non-negative integers.

- Let x = p/q be a rational number, such that the prime factorization of q is not of the form 2m × 5n where m, n are non-negative integers. Then, x has a decimal expansion which is non-terminating repeating.

CLASSIFICATION OF REAL NUMBERS

Real Numbers are classified into rational and irrational numbers.

RATIONAL NUMBERS

A number which can be expressed in the form p/q where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0 is called a rational number.

Examples:

- 4 is a rational number since 4 can be written as 4/1 where 4 and 1 are integers and the denominator 1 ≠ 0.

- ¾, -2/5 are also rational numbers.

- Recurring decimals are also rational numbers (0.333…, 0.111111…, 0.166666…)

Key Point: Between any two numbers, there can be infinite number of other rational numbers.

IRRATIONAL NUMBERS

Numbers which are not rational but which can be represented by points on the number line are called irrational numbers.

Examples: ![]() etc.

etc.

Numbers like π, ε are also irrational numbers.

Key Point: Between any two numbers, there are infinite numbers of irrational numbers.

Another Way of Looking at Rational and Irrational Numbers

- Any terminating or recurring decimal is a rational number.

- Any non-terminating non-recurring decimal is an irrational number.

RULES FOR DIVISIBILITY

In a number of situations, we will need to find the factors of a given number. Some of the factors of a given number can, in a number of situations, be found very easily either by observation or by applying simple rules.

Divisibility by 2

A number divisible by 2 will have an even number as its last digit.

Examples: 128, 246, 2346

Divisibility by 3

A number is divisible by 3 if the sum of its digits is a multiple of 3.

Example: 9123 → 9 + 1 + 2 + 3 = 15 (multiple of 3) ✓

74549 → 7 + 4 + 5 + 4 + 9 = 29 (not a multiple of 3) ✗

Divisibility by 4

A number is divisible by 4 if the number formed with its last two digits is divisible by 4.

Example: 178564 → last two digits: 64 (divisible by 4) ✓

476854 → last two digits: 54 (not divisible by 4) ✗

Divisibility by 5

A number is divisible by 5 if its last digit is 5 or zero.

Examples: 15, 40, 125, 3450

Divisibility by 6

A number is divisible by 6 if it is divisible both by 2 and 3.

Examples: 18, 42, 96

Divisibility by 7

Rule: Take the units digit of the number, double it and subtract this figure from the remaining part of the number. If the result so obtained is divisible by 7, then the original number is divisible by 7.

Example 1: 595

- Units digit: 5, doubled: 10

- Remaining part: 59

- 59 - 10 = 49 (divisible by 7) ✓

Example 2: 967

- Units digit: 7, doubled: 14

- Remaining part: 96

- 96 - 14 = 82 (not divisible by 7) ✗

Divisibility by 8

A number is divisible by 8, if the number formed by the last 3 digits of the number is divisible by 8.

Example: 3816 → last three digits: 816 (divisible by 8) ✓

Divisibility by 9

A number is divisible by 9 if the sum of its digits is a multiple of 9.

Example: 6318 → 6 + 3 + 1 + 8 = 18 (multiple of 9) ✓

Divisibility by 10

A number divisible by 10 should end in zero.

Divisibility by 11

A number is divisible by 11 if the difference between the sum of digits in odd places and the sum of the digits in even places is equal to zero or a multiple of 11.

Example 1: 132

- Sum of digits in odd places: 1 + 2 = 3

- Sum of digits in even places: 3

- Difference: 3 - 3 = 0 ✓

Example 2: 89394811

- Sum of digits in odd places: 8 + 3 + 4 + 1 = 16

- Sum of digits in even places: 9 + 9 + 8 + 1 = 27

- Difference: 27 - 16 = 11 (multiple of 11) ✓

Divisibility by 19

Rule: Take the units digit of the number, double it and add this figure to the remaining part of the number. If the result so obtained is divisible by 19, then the original number is divisible by 19.

Example: 665

- Units digit: 5, doubled: 10

- Remaining part: 66

- 66 + 10 = 76 (divisible by 19) ✓

DECIMAL REPRESENTATION OF RATIONAL NUMBERS

Theorem 1

Let x = p/q be a rational number such that q ≠ 0 and prime factorization of q is of the form 2m × 5n where m, n are non-negative integers then x has a decimal representation which terminates.

Example:

Theorem 2

Let x = p/q be a rational number such that q ≠ 0 and prime factorization of q is not of the form 2m × 5n, where m, n are non-negative integers, then x has a decimal expansion which is non-terminating repeating.

Example:

![]()

| Rational Number | Form of prime factorisation of the denominator | Decimal expansion of rational number |

|---|---|---|

| x = p/q, where p and q are coprime and q ≠ 0 | q = 2m5n where n and m are non-negative integers | terminating |

| x = p/q, where p and q are coprime and q ≠ 0 | q ≠ 2m5n where n and m are non-negative integers | non-terminating |

EUCLID'S DIVISION LEMMA

Euclid's Division Lemma

For any two positive integers a and b, a > b there exist unique integers q and r such that:

a = bq + r (0 ≤ r < b)

Key Relationships:

- HCF(a, b) × LCM(a, b) = a × b

- HCF of two or more prime numbers is always 1

- LCM of two or more prime numbers is equal to their products

SOLVED EXAMPLES

Example 1: Is 7 × 11 × 13 + 11 a composite number?

Solution:

11(7×13 + 1) = 11(91 + 1) = 11 × 92 = 1012

It is a composite number which can be factorized into primes.

Example 2: Find the LCM and HCF of 84, 90 and 120 by applying the prime factorization method.

Solution:

84 = 2² × 3 × 7

90 = 2 × 3² × 5

120 = 2³ × 3 × 5

| Prime factors | Least exponent |

|---|---|

| 2 | 1 |

| 3 | 1 |

| 5 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 |

HCF = 2¹ × 3¹ = 6

| Common prime factors | Greatest exponent |

|---|---|

| 2 | 3 |

| 3 | 2 |

| 5 | 1 |

| 7 | 1 |

LCM = 2³ × 3² × 5¹ × 7¹ = 8 × 9 × 5 × 7 = 2520

Example 3: Given that HCF (306, 657) = 9. Find the LCM (306, 657).

Solution:

HCF (306, 657) × LCM (306, 657) = 306 × 657

⇒ 9 × LCM (306, 657) = 306 × 657

⇒ LCM (306, 657) = (306 × 657)/9 = 34 × 657

⇒ LCM (306, 657) = 22338

Example 4: Prove that √2 is an irrational number.

Solution:

Let assume on the contrary that √2 is a rational number.

Then, there exists positive integer a and b such that √2 = a/b

where, a and b are co primes i.e. their HCF is 1.

⇒ (√2)² = (a/b)²

⇒ 2 = a²/b²

⇒ a² = 2b²

⇒ a² is multiple of 2

⇒ a is a multiple of 2 ....(i)

⇒ a = 2c for some integer c.

⇒ a² = 4c²

⇒ 2b² = 4c²

⇒ b² = 2c²

⇒ b² is a multiple of 2

⇒ b is a multiple of 2 ....(ii)

From (i) and (ii), a and b have at least 2 as a common factor. But this contradicts the fact that a and b are co-prime. This means that √2 is an irrational number.

PRACTICE PROBLEMS

Let's Try - Questions

- What can you say about the prime factorization of the denominators of the following rationales:

- (i) 36.12345

- (ii) 36.5678 (repeating)

- For a pair of integers 151, 16, find the quotient q and the remainder r when the larger number a is divided by the smaller number b and verify that a = bq + r and 0 ≤ r < b.

- Prove that the square of any positive integer of the form 5q + 1 is of the same form.

- 144 cartons of coke cans and 90 cartons of Pepsi cans are to be stacked is a canteen. If each stack is of same height and is to contains cartons of the same drink, what would be the greatest number of cartons each stack would have?

- Show that n² - n is divisible by 2 for every positive integer n.

- Check whether 6n can end with the digit 0 for any natural number.

- An army contingent of 616 members is to march behind an army band of 32 members in a parade. The two groups are to march in the same number of columns. What is the maximum number of columns in which they can march?

- Prove that 3 - √5 is an irrational number.

- Without actually performing the long division, state whether 13/3125 has terminating decimal expansion or not.

Answers:

- Question 2: q = 9 and r = 7

- Question 4: 18

- Question 7: 8