Understanding the Number System: A Complete Overview

The Number System is the foundation of mathematics, encompassing various types of numbers used for counting, measuring, and calculating. This structured system includes Natural Numbers, Whole Numbers, Integers, Rational Numbers, Irrational Numbers, and Real Numbers. Each category holds specific properties and mathematical significance, forming the backbone of arithmetic and algebraic operations.

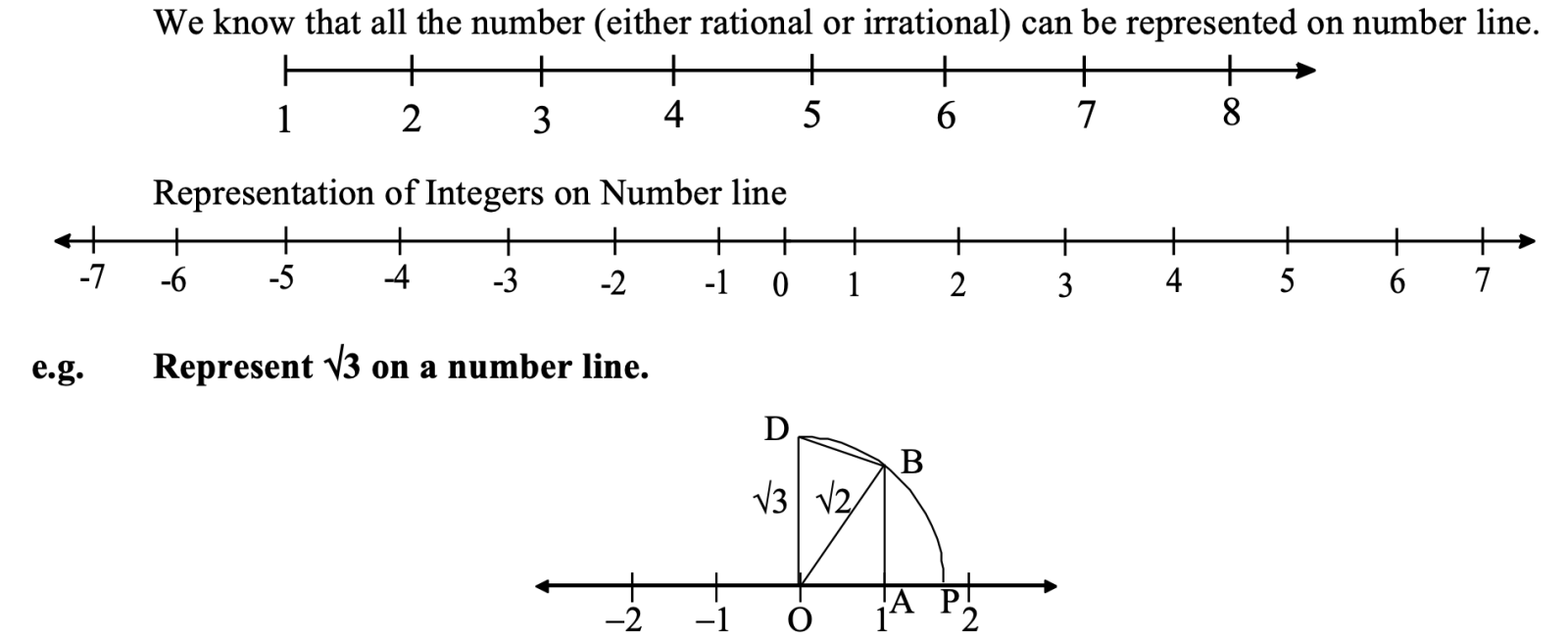

The Number System in Class 8 Maths introduces students to rational and irrational numbers, decimals, whole numbers, and integers. These notes help build a clear understanding of how numbers are classified and represented on the number line. Students also learn about terminating and non-terminating decimals, conversion between fractions and decimals, and operations on rational numbers.

Well-organized Class 8 Number System Notes were revised faster, covering prime factorization, laws of exponents, and square roots. Regular practice enhances arithmetic skills and prepares students for advanced algebra and real-life applications. These notes include solved examples and NCERT based questions frequently asked in exams. Downloadable Class 8 Maths Number System Notes PDF ensures concept clarity and confidence during problem-solving.

1. Classification of Numbers

Natural and Whole Numbers

Natural Numbers are basic counting numbers starting from 1 to infinity (1, 2, 3, …). When zero is included, the set becomes Whole Numbers (0, 1, 2, 3, …).

Integers

Integers extend whole numbers to include negatives. For every integer n, its opposite –n satisfies the relation n + (–n) = 0, making integers closed under addition, subtraction, and multiplication.

Rational Numbers

Rational numbers are expressible as p/q, where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0. They include both terminating (e.g., 3/8 = 0.375) and recurring decimals (e.g., 4/7 = 0.57143…). Operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division on rational numbers follow closure, commutative, and associative properties.

Irrational Numbers

Irrational numbers cannot be expressed as fractions. Their decimal expansions are non-terminating and non-repeating, such as √2 or π (3.1416…). They bridge the gaps between rational numbers on the number line, giving continuity to the real number system.

Real Numbers

When rational and irrational numbers are combined, they form the set of real numbers, denoted by ℝ, encompassing every measurable quantity.

2. Operations and Properties

Both rational and real numbers exhibit key mathematical properties:

-

Closure: The sum or product of two real numbers is real.

-

Commutative: a + b = b + a, and a × b = b × a.

-

Associative: (a + b) + c = a + (b + c).

-

Distributive: a(b + c) = ab + ac.

Irrational numbers follow distinct behaviors the sum of a rational and an irrational number is always irrational, while the product may be rational or irrational depending on the values involved

3. Decimal Representation and Conversions

Decimals represent fractions with denominators as powers of 10.

-

Terminating Decimals: Stop after a finite number of digits (e.g., 0.125).

-

Recurring Decimals: Repeat a pattern endlessly (e.g., 0.333…).

Converting decimals to fractions involves multiplying by 10, 100, or 1000 as per decimal places and simplifying. For recurring decimals, algebraic elimination (subtracting shifted values) is applied to express in p/q form

4. Factors, Multiples, HCF, and LCM

-

Factors are numbers that divide another exactly.

-

Multiples are results of multiplying a number by integers.

-

HCF (Highest Common Factor) is the largest number dividing two or more numbers exactly.

-

LCM (Least Common Multiple) is the smallest number that is a multiple of given numbers.

The relationship between them is:

HCF × LCM = Product of the numbers

5. Divisibility and Number Properties

Divisibility rules simplify checks for factors:

-

By 2 → Last digit is 0, 2, 4, 6, 8

-

By 3 → Sum of digits divisible by 3

-

By 5 → Ends in 0 or 5

-

By 6 → Divisible by both 2 and 3

-

By 9 → Sum of digits divisible by 9

-

By 11 → Difference between sum of digits at odd and even places divisible by 11

02_Number System Theory

6. Squares and Perfect Squares

A square of a number is its product with itself (n²). A perfect square is a number that can be expressed as n² where n is an integer (e.g., 1, 4, 9, 16, 25). Properties include:

-

The square of an even number is even.

-

The square of an odd number is odd

7. Key Number System Formulas

| Formula Name | Mathematical Representation | Explanation |

| Opposite (Additive Inverse) | n + (–n) = 0 | Sum of a number and its negative equals zero |

| Reciprocal (Multiplicative Inverse) | a × (1/a) = 1 | Product of a number and its reciprocal equals one |

| Relationship between HCF and LCM | HCF × LCM = Product of numbers | Connects factorization and multiples |

| Conversion of Terminating Decimal | p/q = Decimal × (10ⁿ / 10ⁿ) | Multiply and simplify by power of 10 |

| Pure Recurring Decimal | x = 0.aaa… ⇒ x = a/9 | Repeated single-digit decimal form |

| Mixed Recurring Decimal | x = (All digits – Non-repeating) / (9’s and 0’s pattern) | For decimals with mixed repetition |

| Even and Odd Squares | (Even)² → Even, (Odd)² → Odd | Defines parity behavior in squaring |

Explain differences between decimal, binary, octal, and hexadecimal

The number system forms the base of all numerical representation and computation. The decimal system is the one we most commonly use in day-to-day life, based on the base 10 principle. It includes ten digits — 0 to 9 — where each digit’s position represents a power of 10. For example, in 472, the number equals (4 × 100) + (7 × 10) + (2 × 1). This system is easy for human interpretation but not efficient for machines.

Binary, on the other hand, is a base-2 system that only uses two symbols, 0 and 1. Each position represents a power of 2, such as 2⁰, 2¹, 2², and so on. Computers use binary because it directly corresponds to the on (1) and off (0) states of electronic switches, allowing for efficient data storage and operations. For example, the decimal 5 equals 101 in binary.

The octal system operates on base 8 and includes digits from 0 to 7. It was historically used in computing because three binary digits (bits) correspond neatly to one octal digit. For instance, binary 110101 becomes 65 in octal. Octal remains helpful in digital electronics for simplifying large binary strings.

Finally, the hexadecimal system uses base 16 and digits from 0–9 along with letters A–F to represent values from 10–15. It is widely used in programming, digital memory addressing, and color coding in web design. Each hexadecimal digit represents four binary bits, making it a compact way to express large binary numbers. For example, 1111 in binary equals F in hexadecimal. Understanding these systems is essential for programming, data analysis, and hardware design, as they improve numerical precision and operational efficiency.

How to convert a decimal number to binary by hand

Converting a decimal number to binary manually uses a straightforward division-by-2 process. This step-by-step method is fundamental to understanding binary systems and helps learners visualize how digital computers represent numbers. To begin, divide the decimal number by 2 and record the remainder. The quotient becomes the new value, which you again divide by 2. Continue until the quotient is zero. The binary equivalent is the remainders read in reverse order.

Let’s take 25 as an example. Divide 25 by 2, which gives a quotient of 12 and a remainder of 1. Next, divide 12 by 2 → quotient 6, remainder 0; then 6 by 2 → 3, remainder 0; 3 by 2 → 1, remainder 1; and finally 1 by 2 → 0, remainder 1. Reading the remainders backward, we get 11001₂ as the binary of 25₁₀. This technique works for any positive integer.

For educational or practical applications, understanding this approach helps in programming, digital logic design, and error checking. Mastering it by hand also strengthens conceptual clarity before using software tools or calculators. Students learning computer architecture often practice this repeatedly to gain accuracy in binary manipulations and to check how computer memory stores integer values as bit patterns.

Why computers use binary instead of decimal

Computers use the binary system because digital hardware operates on two voltage states — typically represented as “on” and “off,” corresponding to 1 and 0 in binary. These binary signals are easy to detect, transmit, and store electronically, unlike decimal digits that would require ten distinct voltage levels, which is impractical and error-prone in electronic circuits.

The binary system provides stability, reliability, and precision. Each bit (binary digit) can represent two possible states, which scale efficiently into bytes (8 bits), words, and larger data blocks. This structure underpins all computer memory and logical operations. Arithmetic logic units (ALUs) inside processors are designed to perform operations using binary addition, subtraction, and bitwise logic. This streamlines both computation and data transfer.

Another reason binary is preferred is its strong fault tolerance. Signal noise or voltage fluctuations rarely cause ambiguity when only two states are used. For instance, distinguishing between 0 volts and 5 volts is much easier than identifying among ten different voltage levels for each decimal digit. Additionally, binary simplifies programming at the machine level, allowing compact representation through hexadecimal shorthand. For example, a single byte like 11110000 can be represented easily as F0₁₆ in hexadecimal form. Thus, binary ensures reliability, cost efficiency, and simplicity in digital computing, making it the universal language of modern electronics.

Practice problems on number system conversions with answers

Gaining proficiency in number system conversions requires hands-on practice. Here are several problems, complete with detailed answers, that cover conversions among decimal, binary, octal, and hexadecimal systems:

-

Convert 181₁₀ to binary:

-

Divide 181 by 2 repeatedly, noting each remainder:

-

181/2 = 90, remainder 1

-

90/2 = 45, remainder 0

-

45/2 = 22, remainder 1

-

22/2 = 11, remainder 0

-

11/2 = 5, remainder 1

-

5/2 = 2, remainder 1

-

2/2 = 1, remainder 0

-

1/2 = 0, remainder 1

-

Reading remainders backwards: 10110101₂

-

-

-

Convert 159₁₀ to octal:

-

159 ÷ 8 = 19, remainder 7

-

19 ÷ 8 = 2, remainder 3

-

2 ÷ 8 = 0, remainder 2

-

Octal answer: 237₈

-

-

Binary to decimal:

-

Binary 10110101₂ = (1×2⁷)+(0×2⁶)+(1×2⁵)+(1×2⁴)+(0×2³)+(1×2²)+(0×2¹)+(1×2⁰) = 128+0+32+16+0+4+0+1 = 181₁₀

-

-

Hexadecimal to binary:

-

Hex 4FB2₁₆ = 0100 1111 1011 0010₂

-

Replicating this approach with additional random numbers ensures you strengthen conversion skills and prepares you for exams or programming applications. Use frequent practice to identify patterns so you can handle any base system question confidently.

What are positional vs non‑positional numeral systems

Numeral systems can be classified as positional or non-positional, a key distinction in mathematical theory and computer science. In a positional system, a digit’s value is determined both by the digit itself and its position within the number. The familiar decimal, binary, octal, and hexadecimal systems are all positional. For instance, in 247₈, the leftmost digit ‘2’ represents 2 × 8² = 128, while ‘7’ on the right means 7 × 8⁰ = 7. The total is the sum of all these weighted values.

In contrast, non-positional systems assign a fixed, intrinsic value to each symbol regardless of placement. Roman numerals exemplify this: ‘I’ is always 1, ‘V’ is always 5, no matter where they appear. Aggregation is achieved through combination rather than multiplication by a positional weight. These systems are less efficient for arithmetic and complex computation, which is why digital systems almost uniformly adopt positional notation.

Understanding the difference is crucial for students and tech professionals because positional systems are foundational for programming, digital electronics, and data encoding.

Show step-by-step conversion examples between all four bases

Understanding conversions between decimal, binary, octal, and hexadecimal is crucial for mastering digital logic and computer programming. Let’s consider the decimal number 3479 and convert it into binary, octal, and hexadecimal:

Decimal to Binary:

-

3479 ÷ 2 = 1739, remainder 1

-

1739 ÷ 2 = 869, remainder 1

-

869 ÷ 2 = 434, remainder 1

-

434 ÷ 2 = 217, remainder 0

-

217 ÷ 2 = 108, remainder 1

-

108 ÷ 2 = 54, remainder 0

-

54 ÷ 2 = 27, remainder 0

-

27 ÷ 2 = 13, remainder 1

-

13 ÷ 2 = 6, remainder 1

-

6 ÷ 2 = 3, remainder 0

-

3 ÷ 2 = 1, remainder 1

-

1 ÷ 2 = 0, remainder 1

Reading the remainders backwards: 110110010111₂

Decimal to Octal:

-

3479 ÷ 8 = 434, remainder 7

-

434 ÷ 8 = 54, remainder 2

-

54 ÷ 8 = 6, remainder 6

-

6 ÷ 8 = 0, remainder 6

Octal answer (bottom-up): 6627₈

Decimal to Hexadecimal:

Convert 3479 decimal to binary (done above: 110110010111).

Group binary digits in fours: 1101 1001 0111

-

1101 = D

-

1001 = 9

-

0111 = 7

Hexadecimal: D97₁₆

Reverse these methods to convert from binary, octal, or hex to decimal by multiplying each digit by the base’s powers and summing up. Practice with random numbers to master inter-base conversions; this skill is essential for both theory-based exams and practical programming.

Conclusion

The Number System unifies all numeric concepts under one logical structure, bridging arithmetic and algebra. Understanding rationality, decimal conversions, divisibility, and factorization forms the essential groundwork for advanced mathematics. Through systematic study, students and educators gain not only computational fluency but also conceptual clarity crucial for higher-level problem-solving.

Number System Theory

Numbers

Natural Numbers: The counting numbers starting from 1 to infinity are called natural numbers: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, …

Whole Numbers: Numbers that start with 0 and include all the natural numbers: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, …

Integers: Whole numbers together with negatives of natural numbers: … −5, −4, −3, −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, …

Number less than zero means you have to add some number to it to get it up to zero. Exact definition: For every real number n, there exists its opposite, denoted −n, such that n + (−n) = 0.

Rational Numbers

Definition: Numbers expressible in the form a/b where a and b are integers and b ≠ 0. These include fractions.

In a fraction, the bottom is the denominator (the size of each part: fourths, fifths, …) and the top is the numerator (how many parts).

Examples converting to decimals:

- 3/8 = 0.375 (terminating decimal)

- 4/7 = 0.57143… (non-terminating recurring)

- 5/9 = 0.55556… (non-terminating recurring)

Every rational number can be represented as a terminating decimal or a non-terminating repeating decimal.

Operations on Rational Numbers

For any two rational numbers p and q:

- Addition: p + q

- Subtraction: p − q

- Multiplication: p × q

- Division: p ÷ q = p/q where q ≠ 0

Properties of Rational Numbers

- Closure: Sum and product of two rational numbers are rational.

- Commutativity: For any p, q, p + q = q + p and p × q = q × p.

- Associativity: For any p, q, r, (p + q) + r = p + (q + r) and (p × q) × r = p × (q × r).

- Difference: The difference of two rational numbers is rational.

- Identities: There exists 0 such that p + 0 = p and 1 such that p × 1 = p for any rational p.

- Inverses: For each rational p, there exists −p such that p + (−p) = 0. For each non-zero rational p, there exists 1/p such that p × (1/p) = 1. Note: zero has no multiplicative inverse.

Converting Decimals to Rational Numbers (a/b)

Case I: Terminating Decimals

Steps:

- Write the number without the decimal point as the numerator.

- In the denominator, write 1 followed by as many zeros as digits after the decimal.

- Simplify the fraction by the GCD of numerator and denominator.

Examples:

- 0.15 = 15/100 = 3/20

- 0.675 = 675/1000 = 27/40

- 0.00026 = 26/100000 = 13/50000

- 15.75 = 1575/100 = 63/4

- −25.6875 = −256875/10000 = −411/16

Case II: Non-terminating Recurring Decimals

Pure recurring: all digits after the decimal repeat (e.g., 0.\overline{8}, 0.\overline{14}).

Mixed recurring: at least one digit after the decimal does not repeat, then a repeating block begins (e.g., 0.4\overline{7}, 0.\!6\overline{3}).

Algebraic Method for Pure Recurring

- Let x be the repeating decimal, write it without bar as an infinite decimal.

- If one digit repeats multiply by 10; two digits repeat multiply by 100; and so on.

- Subtract to eliminate the repeating part, then solve for x.

Example: Express 0.\overline{2} as a fraction.

Let x = 0.222…. Then 10x = 2.222…. Subtract to get 9x = 2. Hence x = 2/9.

Example (mixed): Convert 0.4\overline{7}.

Let x = 0.4777…. Then 10x = 4.777… and 100x = 47.777…. Subtract to get 90x = 43, so x = 43/90.

Shortcut Methods

- Pure recurring: Write the repeating digits once over as many 9s as the number of repeating digits. Examples: 0.\overline{3} = 3/9 = 1/3, 0.\overline{81} = 81/99 = 9/11.

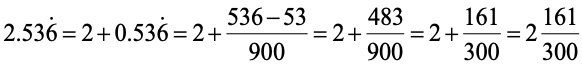

- Mixed recurring: In the numerator, take the number formed by all decimal digits (with the repeating block written once) minus the non-repeating part. In the denominator, write as many 9s as the number of repeating digits followed by as many 0s as non-repeating digits. Examples: 0.1\overline{6} = (16−1)/90 = 15/90 = 1/6, 2.3\overline{45} = (2345−23)/990 = 2322/990 = 129/55.

Insertion of Rational Numbers Between Two Given Rationals

If a and b are rational numbers, then (a + b)/2 is a rational number between them. Repeating the process inserts infinitely many rationals.

Example: Between 2 and 3: first insert 2.5; then between 2.5 and 3 insert 2.75; hence two rationals are 5/2 and 11/4.

Example: Insert three rationals between 1/4 and 1/2 by repeated averages.

Irrational Numbers

Definition: Numbers that cannot be written as p/q with integers p, q and q ≠ 0. They are non-terminating and non-repeating decimals. Examples: √2, √3, √5, √7, √8, √10. Also cube roots of non-perfect cubes such as ∛2, ∛4, ∛6.

π is irrational with approximate rational value 22/7.

Operations on Irrational Numbers

- √2 + √3 ≠ √5 and similarly √5 − √2 ≠ √3.

- The negative of an irrational number is irrational (e.g., −√2).

- Rational + irrational is irrational (e.g., 2 + √3).

- Sum of two irrationals may be irrational or rational: 3√2 + 4√2 = 7√2 (irrational); (2 + √3) + (4 − √3) = 6 (rational).

- Product of a non-zero rational and an irrational is irrational (e.g., 3√2).

- Products of irrationals may be irrational or rational: √6 × √6 = 6 (rational); 3√2 × 2√2 = 6×2 = 12 (rational); other pairings can be irrational.

Representing Rational and Irrational Numbers on the Number Line

All rationals and irrationals can be represented on the number line. For example, to locate √3, construct a right triangle with legs 1 and √2 or use Pythagorean construction to approximate the position.

Real Numbers

Definition: The set of real numbers is the union of rational and irrational numbers.

Properties of Real Numbers

- Closure: Sum and product of two reals are real.

- Commutativity:a + b = b + a, ab = ba.

- Associativity:(a + b) + c = a + (b + c), (ab)c = a(bc).

- Distributive:a(b + c) = ab + ac and (a + b)c = ac + bc.

- Reciprocals: If a ≠ 0, then 1/a exists and a × (1/a) = 1.

Decimals

Fractions with denominators 10 or powers of 10 (e.g., 10, 100, 1000) can be written in decimal form: 0.5, 0.63, 3.28.

A decimal has two parts separated by a decimal point: the whole number part to the left and the decimal part to the right. Example: in 32.65, whole part = 32, decimal part = 65.

Decimal Places

The number of digits in the decimal part equals the number of decimal places. Examples: 3.42 has 2 places; 19.205 has 3 places.

Convert a Decimal to a Fraction

- Write the number without the decimal point as the numerator.

- Denominator is 1 followed by as many zeros as decimal places.

- Reduce to simplest form. Example: 13.484 = 13484/1000 = 3371/250.

Convert a Fraction to a Decimal by Division

- Divide numerator by denominator.

- If needed, place a decimal point and append zeros to continue division until remainder is zero or desired places are reached.

Rounding Off Decimals

To the Nearest Whole Number

- Retain all digits of the whole part, omit decimal part.

- If the first omitted digit is 5 or more, increase the last retained digit by 1.

To a Required Number of Decimal Places

- Retain as many digits after the decimal as required.

- If the first omitted digit is 5 or more, increase the last retained digit by 1.

Terminating and Non-terminating Decimals

A decimal is terminating if the division ends in finitely many steps (e.g., 1/2 = 0.5, 41/100 = 0.41). If the division continues indefinitely without zero remainder, it is non-terminating (e.g., 1/17 = 0.05882352…).

Repeating or Recurring Decimals

If in a decimal, a digit or a set of digits in the decimal part is repeated continuously, then such a number is called a recurring or repeating decimal.

In a recurring decimal, if a single digit is repeated, then it is expressed by putting a dot on it. If a set of digits is repeated, it is expressed by putting a bar on the set or putting a dot over first and last digits of the repeated set.

(i) 1/3 = 0.333... = 0.3

(ii) 5/6 = 0.8333.... = 0.83

(iii) 9/37 = 0.24323... = 0.243(or 0.243)

PURE RECURRING DECIMALS:

A decimal in which all the digits in the decimal part are repeated, is called a pure recurring decimal.

e.g. 1/3 = 0.3, 3/7 = 0.428571428571.... = 0.428571 are pure recurring decimals.

Mixed Recurring Decimals

A decimal in which some of the digits in the decimal part are repeated and the rest are not repeated, is called a mixed recurring decimal. 1

e.g. 5/6= 0.8333... = 0.83 is a mixed recurring decimal.

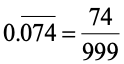

CONVERTING A PURE RECURRING DECIMAL INTO VULGAR FRACTION (SHORT CUT METHOD):

Write the repeated digits only once in the numerator and take as many nines in the denominator as is the number of repeating digits.

(i)

(ii)

(iii)

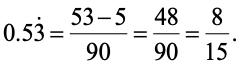

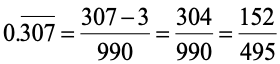

CONVERTING A MIXED RECURRING DECIMAL INTO VULGAR FRACTION (SHORT CUT METHOD):

In the numerator take the difference between the number formed by all the digits in the decimal part (taking repeated digits only once) and the number formed by the digits which are not repeated. In the denominator, take the number formed by as many nines as there are repeating digits followed by as many zeros as is the number of non-repeating digits.

Ex.:

(i)

(ii)

(iii)

FACTORS AND MULTIPLES:

If a number ‘a’ divides another number ‘b’ exactly, we say that ‘a’ is a factor of ‘b’ and ‘b’ is a multiple of ‘a’.

Thus, a factor of a number is an exact divisor of that number.

And, a number is said to be a multiple of any of its factors.

EVEN NUMBERS:

All the multiples of 2 are called even numbers.

e.g. 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, etc. are all even numbers.

ODD NUMBERS:

Numbers which are not multiples of 2 are called odd numbers.

e.g. 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, etc. are all odd numbers.

PRIME NUMBERS:

Each of the numbers which has exactly two factors, namely, 1 and the number itself, is called a prime number.

e.g. 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, etc. are all prime numbers.

COMPOSITE NUMBERS:

Numbers having more than two factors are known as composite numbers.

e.g. 4, 6, 8, 9, 10, 12, etc. are all composite numbers.

Note: (i) 1 is neither prime nor composite.

(ii) 2 is the lowest prime number.

(iii) 2 is the only even prime number.

TESTS OF DIVISIBILITY

TEST OF DIVISIBILITY BY 2:

A number is divisible by 2, if its units digit is any of the digits 0, 2, 4, 6 and 8.

e.g. Each of the numbers 24, 36, 78, 192, 310, 214166 is divisible by 2.

TEST OF DIVISIBILITY BY 3:

A number is divisible by 3, if the sum of its digits is divisible by 3.

e.g. (i) Consider the number 349524.

Sum of its digits = (3 + 4 + 9 + 5 + 2 + 4) = 27, which is divisible by 3.

349524 is divisible by 3.

(ii) Consider the number 871423

Sum of its digits = (8 + 7 + 1 + 4 + 2 + 3) = 25, which is not divisible by 3.

871423 is not divisible by 3.

TEST OF DIVISIBILITY BY 4:

A number is divisible by 4, if the number formed by its last two digits is divisible by 4.

e.g. (i) Consider the number 15632.

The number formed by its last two digits is 32, which is divisible by 4.

15632 is divisible by 4.

(ii) Consider the number 19374.

The number formed by its last two digits is 74, which is not divisible by 4.

19374 is not divisible by 4.

TEST OF DIVISIBILITY BY 5:

A number is divisible by 5, if its units digit is either 0 or 5.

e.g. The numbers 245, 16260, 27915, 411115 are all divisible by 5.

TEST OF DIVISIBILITY BY 6:

A number is divisible by 6, if it is divisible by 2 as well as 3.

e.g. (i) Consider the number 753216. Since its units digit is 6, so it is divisible by 2.

Sum of its digits = (7 + 5 + 3 + 2 + 1 + 6) = 24, which is divisible by 3.

753216 is divisible by both 2 and 3 and is therefore divisible by 6.

(ii) Consider the number 453212. Since, its units digit is 2, so it is divisible by 2. Sum of its digits = (4 + 5 + 3 + 2 + 1 + 2) = 17, which is not divisible by 3.

453212 is not divisible by 6.

Note: If a number is divisible by two co-primes, then it is also divisible by their product.

TEST OF DIVISIBILITY BY 7:

The last digit of the number is multiplied by 2 and then subtracted from the remaining number; this process is continued till get the smallest number. Then check it whether divisible by 7 or not.

e.g. (a) 112: 11 – 2 × 2 = 7. As 7 is divisible by 7, the number 112 is also divisible by 7.

(b) 2961:

Step I: 2961: 296 – 1 × 2 = 296 – 2 = 294.

Step II: 29 – 4 × 2 = 29 – 8 = 21

As 21 is divisible by 7, the number is also divisible by 7.

(c) 55277838:

5527783 8: 5527783 – 8 × 2 ⇒ 5527783 – 16 = 5527767

552776 7: 552776 – 7 × 2 ⇒ 552776 – 14 = 552762

55276 2: 55276 – 2 × 2 ⇒ 55276 – 4 = 55272

5527 2: 5527 – 2 × 2 ⇒ 5527 – 4 = 5523

552 3: 552 – 3 × 2 ⇒ 552 – 6 = 546

54 6: 54 – 6 × 2 = 54 – 12 = 42

As 42 is divisible by 7, the number is also divisible by 7.

Test of Divisibility by 8:

A number is divisible by 8, if the number formed by its last three digits is divisible by 8.

e.g. (i) Consider the number 29512.

The number formed by its last three digits is 512, which is divisible by 8.

So, 29512 is divisible by 8.

(ii) Consider the number 16942.

The number formed by its last three digits is 942, which is not divisible by 8.

∴ 16942 is not divisible by 8.

TEST OF DIVISIBILITY BY 9:

A number is divisible by 9, if the sum of its digits is divisible by 9.

e.g. (i) Consider the number 517248.

Sum of its digits = (5 + 1 + 7 + 2 + 4 + 8) = 27, which is divisible by 9.

∴ 517248 is divisible by 9.

(ii) Consider the number 641857.

Sum of its digits = (6 + 4 + 1 + 8 + 5 + 7) = 31, which is not divisible by 9.

∴ 641857 is not divisible by 9.

TEST OF DIVISIBILITY BY 10:

A number is divisible by 10, if its units digit is 0.

e.g. The numbers 1110, 301020, 15670, 19250 are all divisible by 10.

TEST OF DIVISIBILITY BY 11:

A number is divisible by 11, if the difference between the sum of its digits at odd places and sum of the digits at even places is either 0 or a number divisible by 11.

e.g. (i) Consider the number 749859.

(Sum of digits at odd places) – (Sum of digits at even places)

= (9 + 8 + 4) – (5 + 9 + 7) = 0.

∴ 749859 is divisible by 11.

(ii) Consider the number 8192657.

(Sum of digits at odd places) – (Sum of digits at even places)

= (7 + 6 + 9 + 8) – (5 + 2 + 1) = 30 – 8 = 22, which is divisible by 11.

∴ 8192657 is divisible by 11.

(iii) Consider the number 5702211

(Sum of digits at even places) – (Sum of digits at odd places)

= (1 + 2 + 7) – (1 + 2 + 0 + 5) = (10 – 8) = 2, which is not divisible by 11.

∴ 5702211 is not divisible by 11.

PRIME FACTORS:

A factor of a given number is called a prime factor if this factor is a prime number.

e.g. The factors of 42 are 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 14, 21 and 42. Out of these 2, 3 and 7 are prime numbers. therefore, 2, 3 and 7 are the prime factors of 42.

COMMON FACTORS:

A number which divides each one of the given numbers exactly, is called a common factor of each of the given numbers.

e.g. 4 divides each one of 212 and 356 exactly. Therefore, 4 is a common factor of 212 and 356.

H.C.F. (HIGHEST COMMON FACTOR) OR G.C.D. (GREATEST COMMON DIVISOR)

H.C.F. or G.C.D. of two or more numbers is the greatest number that divides each one of them exactly.

e.g. Consider the numbers 36 and 54.

F(36) = Set of all factors of 36 = {1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 9, 12, 18, 36}

F(54) = Set of all factors of 54 = {1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 18, 27, 54}

F(36) ∩ F(54) = Set of all common factors of 36 and 54

= {1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 18}.

The greatest number in F(36) ∩ F(54) is 18.

H.C.F. of 36 and 54 = 18.

METHODS OF FINDING THE H.C.F. OF GIVEN NUMBERS:

Prime Factorisation Method :

Suppose we have to find the H.C.F. of two or more numbers.

Step 1: Express each one of the given numbers as the product of prime factors.

Step 2: The product of terms containing least powers of common prime factors gives the H.C.F. of the given numbers.

LCM (LEAST COMMON TYPE)

The L.C.M. of two or more numbers is the least natural number which is a multiple of each of the given numbers.

e.g. Consider the number 12 and 18.

M(12) = Set of multiples of 12 = {12, 24, 36, 48, 60, 72, …..}

M(18) = Set of multiples of 18 = {18, 36, 54, 72, 90, …..}

M(12) ∩ M(18) = Set of common multiples of 12 and 18 = {36, 72, …..}

Least of these number is 36.

L.C.M. of 12 and 18 = 36.

METHODS OF FINDING THE L.C.M. OF GIVEN NUMBERS:

Prime Factorisation Method :

Suppose we have to find the L.C.M. of two or more numbers.

Step 1: Express each one of the given numbers as the product of prime factors.

Step 2: The product of all the different prime factors each raised to highest power that appears in the prime factorisation of any of the given numbers, gives the L.C.M. of the given numbers.

RELATION BETWEEN H.C.F. AND L.C.M. OF TWO NUMBERS:

We have:

Product of two given numbers = Product of their H.C.F. and L.C.M.

SQUARES:

The square of a number is that number raised to the power 2.

e.g. (i) Square of 5 = 52 = 5 × 5 = 25 ;

(ii) Square of 6 = 62 = 6 × 6 = 36 ;

(iii) Square of 2/3 = (2/3)2 = 2/3 × 2/3 = 4/9

(iv) Square of 0.2 = (0.2)2 = 0.2 × 0.2 = 0.04.

PERFECT SQUARES:

A natural number is called a perfect square, if it is the square of some other natural number.

e.g. We know that

1 = 12, 4 = 22, 9 = 32, 16 = 42, 25 = 52, 36 = 62, and so on.

Thus, each of the numbers 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36 etc. is a perfect square.

TEST:

A given number is a perfect square, if it can be expressed as the product of exact number of parts of equal factors.

SOME PROPERTIES OF SQUARES OF NUMBERS:

- The square of an even number is always an even number.

e.g. (i) 2 is even number is always an even number.

(ii) 4 is even and 42 = 16, which is even.

- The square of an odd number is always an odd number.

e.g. (i) 3 odd and 32 = 9, which is odd.

(ii) 5 is odd and 52 = 25, which is odd.

III. The square of a proper fraction is less than the proper fraction.

e.g.

(i) 1/2 is a proper fraction and (1/2)2 = 1/2 × 1/2 = 1/4 < 1/2

(ii) 2/3 is a proper fraction and (2/3)2 = 2/3 × 2/2 = 4/9 < 2/3

- The square of a decimal fraction less than 1 is smaller than the decimal.

e.g. (i) 0.1 < 1 and (0.1)2 = 0.1× 0.1 = 0.01 < 0.1.

(ii) 0.3 < 1 and (0.3)2 = 0.3 × 0.3 = 0.09 < 0.3.

- A number ending in 2, 3, 7 or 8 is never a perfect square.

e.g. The number 72, 243, 567 and 1098 end in 2, 3, 7 and 8 respectively. So, none of them is a perfect square.

- A number ending in an odd number of zeros is never a perfect square.

e.g. The numbers 690, 87000 and 4900000 end in one zero, three zeros and five zeros respectively. So, none of them is a perfect square.

SQUARE ROOT

The square root of a number x is that number which when multiplied by itself gives x as the product.

We denote the square root of a number x by root x.

e.g. Since 5 × 5 = 25, so root 25 = 5.

TO FIND THE SQUARE ROOT OF A GIVEN NUMBER USING PRIME FACTORIZATION METHOD:

When a given number is a perfect square, we find its square root as given below:

- Step 1: Resolve the given number into prime factors.

- Step 2: Make pairs of similar factors.

- Step 3: The product of prime factors, chosen one out of every pair, gives the square root of the given number.

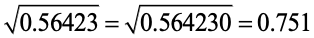

SQUARE ROOT OF NUMBERS IN DECIMAL FORM:

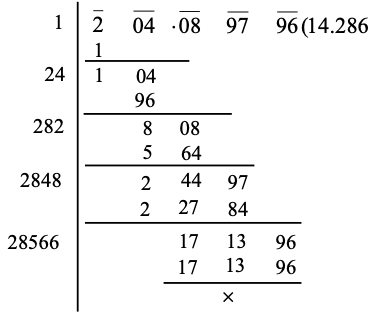

METHOD:

Make the number of decimal places even by affixing a zero, if necessary. Now, mark periods and find out the square root by the long-division method. Put the decimal point in the square root as soon as the integral part is exhausted.

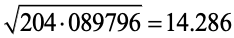

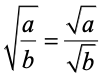

Ex.: Find the square root of 204 089796.

Sol. Here, the number of decimal places is already even. So, mark the periods and proceed as follows :

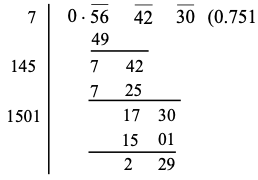

FINDING THE SQUARE ROOTS OF NUMBERS WHICH ARE NOT PERFECT SQUARES:

Ex.: Find the value of upto 3 places of decimal.

Sol. In order to make an even number of decimal places, we affix a zero at the end of the given decimal.

Now, mark off the periods and extract the square root as shown below.

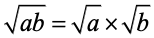

SQAURE ROOT OF FRACTIONS

For any positive real numbers a and b, we have :

(i)

(ii)

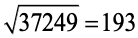

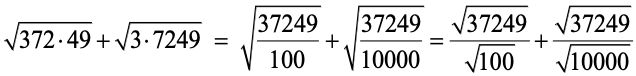

Ex.: Find the value of as shown below :

Sol.

So,

=