Introduction to Probability and Random Experiments

Probability theory forms the mathematical foundation for understanding uncertainty and randomness in various fields, from statistics and data science to finance and engineering. At its core, probability quantifies the likelihood of events occurring in situations where outcomes cannot be predicted with certainty. A random experiment represents any process whose outcome cannot be determined beforehand, even though all possible outcomes are known. Classic examples include rolling dice, flipping coins, or drawing cards from a deck—each representing scenarios where chance governs the results.

The fundamental principle of probability states that if a random experiment can result in N equally likely outcomes, with exactly n outcomes favoring event A, then the probability of event A equals n/N. This ratio, bounded between 0 and 1, provides a mathematical framework for quantifying uncertainty. When probability equals 0, the event is impossible; when it equals 1, the event is certain to occur.

Sample Spaces, Events, and Their Classifications

The sample space (denoted as S) encompasses all possible outcomes of a random experiment, with each individual outcome called a sample point. Understanding sample spaces is crucial for probability calculations, as they define the universe of possibilities for any given experiment. For instance, when rolling two dice, the sample space contains 36 ordered pairs representing all possible combinations.

Events, which are subsets of the sample space, can be classified into several important categories. Simple events contain only one sample point, representing a single specific outcome. Compound events comprise multiple sample points and can be expressed as unions of simple events. Events may also be mutually exclusive (cannot occur simultaneously), independent (occurrence of one doesn't affect the other), or exhaustive (at least one must occur in any trial). These classifications are essential for applying the correct probability formulas and understanding the relationships between different outcomes.

Set Theory Principles in Probability

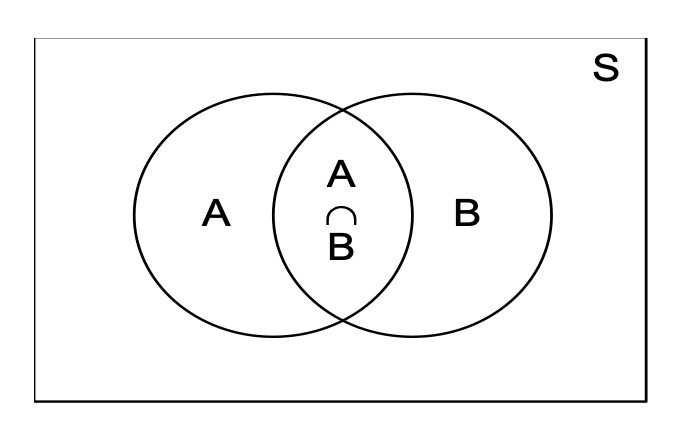

Probability theory extensively utilizes set operations to describe relationships between events. The union of events (A ∪ B) represents the occurrence of at least one event, while the intersection (A ∩ B) indicates simultaneous occurrence. The complement of an event (A' or Ā) represents its non-occurrence. These set-theoretic principles enable complex probability calculations through systematic application of fundamental rules.

The addition rule for probability states that P(A ∪ B) = P(A) + P(B) - P(A ∩ B), accounting for the overlap between events to avoid double-counting. For three events, this extends to include all pairwise intersections and the triple intersection. Understanding odds provides an alternative perspective: if m cases favor event A and n cases don't, the odds in favor equal m:n, while odds against equal n:m.

Conditional Probability and Independence

Conditional probability P(B|A) measures the likelihood of event B occurring given that event A has already occurred. This concept is fundamental in sequential processes and decision-making scenarios where prior information influences subsequent probabilities. Mathematically, P(B|A) = P(A ∩ B)/P(A), provided P(A) > 0. This formula reflects how the sample space effectively reduces to event A when calculating the conditional probability.

Independence between events represents a special case where P(B|A) = P(B), meaning knowledge of A's occurrence doesn't affect B's probability. For independent events, the multiplication rule simplifies to P(A ∩ B) = P(A) × P(B). This property is crucial in many applications, from quality control in manufacturing to risk assessment in insurance, where multiple independent factors contribute to overall outcomes.

Advanced Theorems: Total Probability and Bayes' Theorem

The Total Probability Theorem provides a systematic approach for calculating event probabilities when the sample space can be partitioned into mutually exclusive and exhaustive events. If A₁, A₂, ..., Aₙ partition the sample space, then P(A) = Σ P(Aᵢ) × P(A|Aᵢ). This theorem proves invaluable when direct probability calculation is difficult but conditional probabilities are known.

Bayes' Theorem, also known as the inverse probability theorem, enables updating probability assessments based on new evidence. Given that event A has occurred, the probability that it resulted from cause Aᵢ equals P(Aᵢ|A) = [P(Aᵢ) × P(A|Aᵢ)]/P(A). This theorem has profound applications in medical diagnosis, machine learning algorithms, spam filtering, and forensic analysis, where posterior probabilities must be calculated from prior knowledge and observed evidence.

Binomial Distribution and Repeated Trials

The binomial distribution models scenarios involving repeated independent trials with two possible outcomes (success or failure). When conducting n trials with success probability p and failure probability q = 1-p, the probability of exactly r successes follows the formula: P(X = r) = ⁿCᵣ × pʳ × qⁿ⁻ʳ. This distribution is fundamental in quality control, opinion polling, and biological experiments where binary outcomes are observed repeatedly.

The binomial coefficient ⁿCᵣ represents the number of ways to choose r successes from n trials, accounting for all possible orderings. Applications range from calculating defect rates in manufacturing to predicting election outcomes based on polling data. Understanding binomial probabilities enables researchers and analysts to make informed decisions about sample sizes and confidence levels in experimental design.

Practical Applications and Problem-Solving Strategies

Mastering probability requires systematic problem-solving approaches. First, clearly identify the sample space and relevant events. Second, determine whether events are independent, mutually exclusive, or conditional. Third, apply appropriate formulas based on these relationships. For complex problems, tree diagrams and probability tables can visualize relationships and organize calculations effectively.

Real-world applications demonstrate probability's versatility. In finance, probability models assess investment risks and option pricing. Healthcare professionals use conditional probability for diagnostic testing and treatment efficacy evaluation. Engineers apply reliability theory based on probability to design fail-safe systems. Data scientists leverage probability distributions for predictive modeling and statistical inference.

Quick Reference: Essential Probability Formulas

| Formula Name | Mathematical Representation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Probability | P(A) = n/N | Ratio of favorable outcomes to total outcomes |

| Complement Rule | P(A') = 1 - P(A) | Probability of event not occurring |

| Addition Rule | P(A ∪ B) = P(A) + P(B) - P(A ∩ B) | Probability of at least one event occurring |

| Multiplication Rule (Independent) | P(A ∩ B) = P(A) × P(B) | Probability of both independent events occurring |

| Conditional Probability | P(B|A) = P(A ∩ B)/P(A) | Probability of B given A has occurred |

| Total Probability | P(A) = Σ P(Aᵢ) × P(A|Aᵢ) | Sum of weighted conditional probabilities |

| Bayes' Theorem | P(Aᵢ|A) = [P(Aᵢ) × P(A|Aᵢ)]/P(A) | Posterior probability given evidence |

| Binomial Probability | P(X = r) = ⁿCᵣ × pʳ × qⁿ⁻ʳ | Probability of r successes in n trials |

| Union of Complements | P(A' ∪ B') = 1 - P(A ∩ B) | Probability that at least one event doesn't occur |

| Three Events Union | P(A ∪ B ∪ C) = P(A) + P(B) + P(C) - P(A ∩ B) - P(A ∩ C) - P(B ∩ C) + P(A ∩ B ∩ C) | Inclusion-exclusion principle for three events |

Random Experiment

An experiment, whose all possible outcomes are known in advance but the outcome of any specific performance can not predicted before the completion of the experiment, is known as random experiment.

Sample space and Sample Point

A set of all possible outcomes associated with same random experiment is called sample space and is usually denoted by ‘S’. Each element of a sample space is called a sample point.

Event

An event is a subset of sample space.

Simple Event and Compound Event

If an event is a set containing only one element of the sample space, then it is called a

simple event.

A compound event is one that can be represented as a union of simple events.

Probability

If a random experiment can result in any one of N different equally likely outcomes, and if exactly n of these outcomes favour A, then the probability of event A,

P(A) = n / N =

no. of favourable cases / total number of cases

0 ≤ P(A) ≤ 1, P(ϕ) = 0 and P(S) = 1.

Ex.: In a single cast with two fair dice the chance of throwing two 4’s is

(A) 1/18

(B) 1/9

(C) 1/36

(D) 1/12

Solution: (C).

There are 6 × 6 equally likely cases (as any face of any die may turn up) ⇒ 36 possible outcomes. For this event, only one outcome (4-4) is favourable.

∴ Probability = 1/36.

Mutually Exclusive Events

A set of events is said to be mutually exclusive if the occurrence of one of them precludes the occurrence of any of the other events.

Independent Events

Events are said to be independent if the occurrence or non-occurrence of one does not affect the occurrence or non-occurrence of other.

Exhaustive Event

A set of events is said to be exhaustive if the performance of random experiment always result in the occurrence of atleast one of them.

SET THEORETIC PRINCIPLES

If ‘A’ and ‘B’ be any two events of the sample space then

- 1. A ∪ B would stand for occurrence of at least one of them.

- 2. A ∩ B stands for simultaneous occurrence of A and B.

- 3. &overline;A (or A') stands for non-occurrence of A

- 4. &overline;A ∩ &overline;B (or A' ∩ B') stands for non-occurrence of both A and B.

- 5. If A and B are any two events, Then P(A ∪ B) = P(A) + P(B) - P(A ∩ B)

- 6. P(A') = 1 - P(A)

- 7. P(A' ∪ B') = 1 - P(A ∩ B)

- 8. If A, B, C are any three events of the sample space, then P(A ∪ B ∪ C) = P(A) + P(B) + P(C) – P(A ∩ B) – P(A ∩ C) – P(B ∩ C) + P(A ∩ B ∩ C)

- 9. If out of m + n equally likely, mutually exclusive and exhaustive cases, m cases are favourable to an event A and n are not favourable to the event A, m : n is called odds in favour of A, n : m is called odds against the event A.

Ex.: From a pack of 52 cards two cards are drawn at random. Then the probability that one card is of spade and one card is of diamond is

(A) 3/17

(B) 2/17

(C) 13/102

(D) none of these

Solution:(C).

Let E2 be the event that one card is of spade and one is of diamond then n(E2) = number of elements in E2 = number of ways in which one card of spade can be selected out of 13 spade cards and one card of diamond can be selected out of 13 diamond cards. = 13C1 × 13C1 = 13 × 13 = 169

∴ P(E2) = n(E2)/n(S) = 169/1326 = 13/102

CONDITIONAL PROBABILITY

The probability of occurrence of an event B when it is known that some event A has occurred is called a conditional probability and is denoted by P(B/A). The symbol P(B/A) is usually read '‘the probability that B occurs given that A occurs” or ”simply probability of B, given A”.

Consider two events ‘A’ and ‘B’ of sample space S. When it is known that event ‘A’ has occurred, it means that sample space would reduce to the sample points representing event A. Now for P(B/A) we must look for the sample points representing the simultaneous occurrence of A and B i.e. sample points in A∩B.

⇒ P(B/A) = n(A ∩ B)n(A) = n(A ∩ B)n(S)n(A)n(S) = P(A ∩ B)P(A)

Thus P(B/A) = P(A ∩ B) P(A) , where 0 < P(A) ≤ 1; Similarly, P(A/B) = P(A ∩ B) P(B) , 0 < P(B) ≤ 1

Hence, P(A ∩ B) = { P(A) · P(B / A), P(A) > 0 P(B) · P(A / B), P(B) > 0 }

Independent Events

Two events A and B are said to be independent if occurrence or non-occurrence of one does not affect the occurrence or non-occurrence of the other,

i.e. P(B/A) = P(B), P(A) ≠ 0 similarly P(A/B) = P(A), P(B) ≠ 0

P(B/A) = P(A ∩ B) / P(A) = P(B) ⇒ P(A ∩ B) = P(A) · P(B)

Ex.: An event A1 can happen with probability 0.4 and event A2 can happen with probability 0.3, then the probability that exactly one of them happens is

(A) 0.24

(B) 0.7

(C) 0.46

(D) none of these

Solution: (C).

The probability that A1 happens is p1 = 0.4

∴ The probability that A1 fails is 1 − p1 = 0.6

Also the probability that A2 happens is p2 = 0.3

Now, the chance that A1 happens and A2 fails is p1(1 − p2) and the chance that A1 fails and A2 happens is p2(1 − p1)

The probability that one and only one of them happens is

p1(1 - p2) + p2(1 - p1) = p1 + p2 - 2p1p2 = 0.46

Total Probability Theorem and Bayes' Theorem

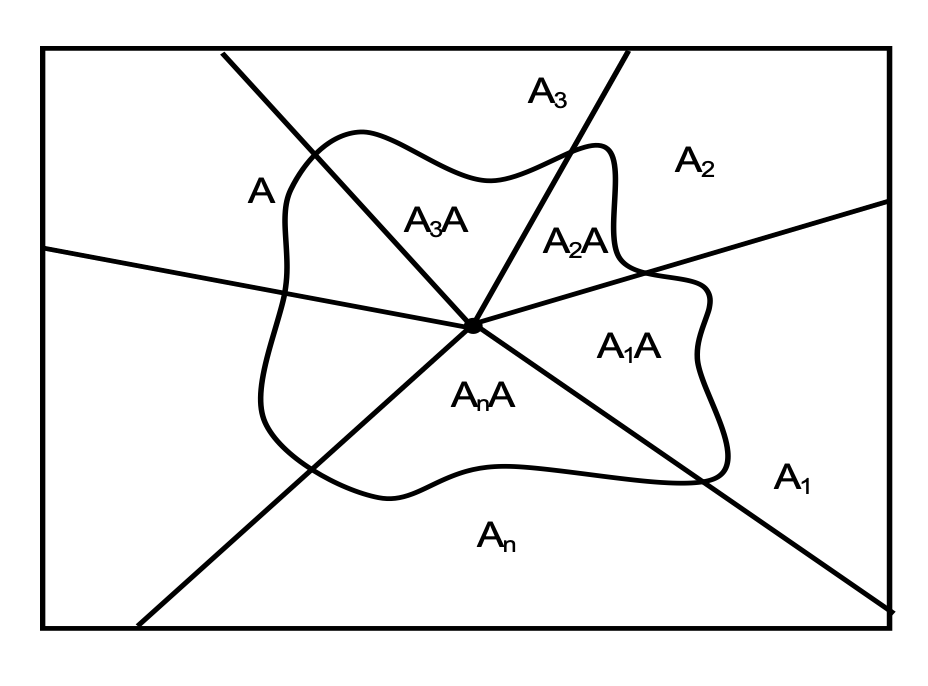

Partition of Sample Space

Consider a sample space ‘S’. Let A1, A2, ⋯, An be the set of mutually exclusive and exhaustive subsets of sample space S.

These A1, A2, ⋯, An events are said to partition the sample space into n parts.

We have Ai ∩ Aj = ∅ for i ≠ j, 1 ≤ i, j ≤ n

And ∑ni=1 P(Ai) = 1

Total Probability Theorem

Let ‘A’ be any event of S. We can write A = (A1 ∩ A) ∪ (A2 ∩ A) ∪ … ∪ (An ∩ A). As A1, A2, …, An are mutually exclusive, (A1 ∩ A), (A2 ∩ A), …, (An ∩ A) would also be mutually exclusive.

⇒ P(A) = P(A1 ∩ A) + P(A2 ∩ A) + … + P(An ∩ A)

= P(A1) · P(A / A1) + P(A2) · P(A / A2) + … + P(An) · P(A / An)

⇒ P(A) = ∑i=1n P(Ai) · P(A / Ai)

This is known as the total probability of the event A.

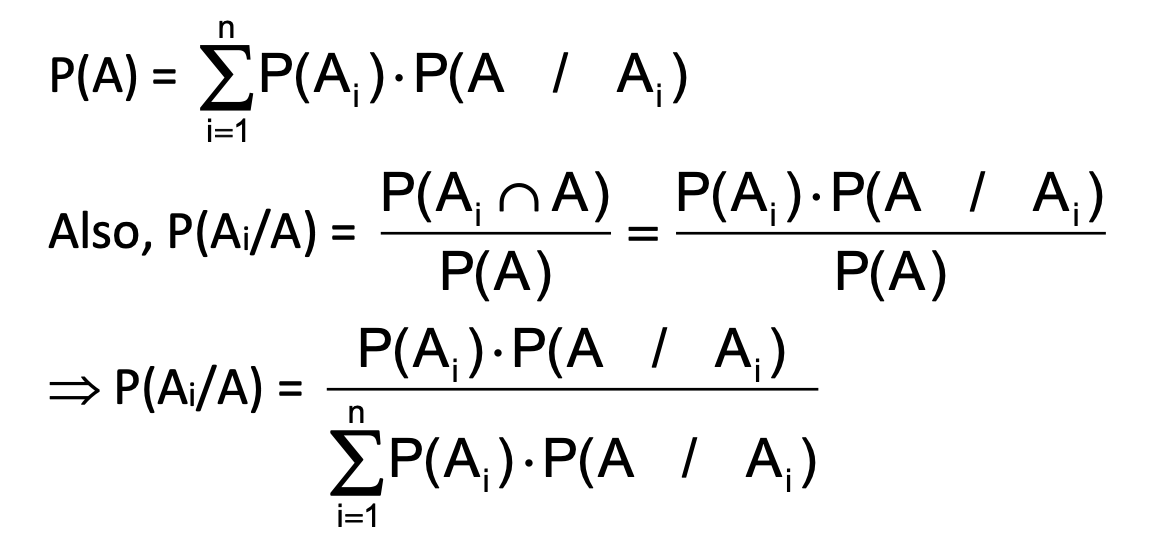

Bayes’ Theorem

This theorem at times is also called inverse probability theorem.

Let us consider any event ‘A’ of sample space ‘S’ (as in the previous section). This event would have occurred due to the different causes (or due to the occurrence of any of the event A₁, A₂, ⋯ Aₙ).

Now, let us say that event A is found to have occurred and we have to find the probability that it has occurred to the occurrence of cause, say Ai.

That means we are interested in P(Ai/A). These types of problems are solved with the help of Bayes’ theorem.

From total probability theorem we get P(A) = ∑ni=1 P(Ai) · P(A | Ai)

Also, P(Ai/A) = [P(Ai ∩ A)] / P(A) = [P(Ai) · P(A | Ai)] / P(A)

⇒ P(Ai/A) = [P(Ai) · P(A | Ai)] / [∑ni=1 P(Ai) · P(A | Ai)]

This result is known as Bayes’ theorem.

BINOMIAL TRIALS AND BINOMIAL DISTRIBUTION

A probability distribution representing the binomial trials is said to be binomial distribution.

Let us consider a Binomial experiment which has been repeated ‘n’ times. Let the probability of success and failure in any trial be p and q respectively and we are interested in the probability of occurrence of exactly ‘r’ successes in these n trials. Now number of ways of choosing ‘r’ success in ‘n’ trials = nCr. Probability of ‘r’ successes and (n-r) failures is pr×qn-r. Thus probability of having exactly r successes = nCr×pr×qn-r.

Formulas and Concepts

- If a random experiment can result in any one of N different equally likely outcomes, and if exactly n of these outcomes correspond to A, then the probability of event A,

P(A) = n / N. - If ‘A’ and ‘B’ be any two events of the sample space then

- A ∪ B would stand for occurrence of at least one of them.

- A (or A′ ∩ B′) stands for non-occurrence of both A and B.

- A ⊆ B stands for ‘the occurrence of A implies the occurrence of B’.

- A̅ (or A′) stands for non-occurrence of A.

- A̅ ∩ B̅ – P(A ∩ B)

- P(A′ ∪ B′) = 1 – P(A ∩ B)

- If out of m + n equally likely, mutually exclusive and exhaustive cases, m cases are favourable to an event and n are not favourable to the event A,

m : n is called odds in favour of A, n : m is called odds against the event A.

- The probability of occurrence of an event B when it is known that some event A has occurred is called a condition probability and is denoted by P(B/A).

P(B/A) = P(A ∩ B) / P(A), 0 < P(A) ≤ 1,P(A ∩ B) =P(A) · P(B/A), P(A) > 0 P(B) · P(A/B), P(B) > 0

- Let us consider a Binomial experiment which has been repeated ‘n’ times. Let the probability of success and failure in any trial be p and q respectively and we are interested in the probability of occurrence of exactly ‘r’ successes in these n trials. Now number of ways of choosing ‘r’ success in ‘n’ trials = nCr. Probability of ‘r’ successes and (n–r) failures is pr·qn–r. Thus probability of having exactly r successes = nCr·pr·qn–r

- Let us consider any event ‘A’ of sample space ‘S’ (as in the previous section). Let us say that event A is found to have occurred and we have to find the probability that it has occurred to the occurrence of cause, say Ai.

Probability theory provides the mathematical framework for quantifying uncertainty and making informed decisions under randomness. From basic concepts of sample spaces and events to advanced applications of Bayes' theorem and binomial distributions, these principles underpin modern statistics, data science, and risk analysis. Mastery of probability enables professionals across disciplines to model complex systems, assess risks, and extract meaningful insights from data. Whether analyzing experimental results, developing machine learning algorithms, or making strategic business decisions, probability theory remains an indispensable tool for understanding and navigating uncertainty in our increasingly data-driven world.

Solved Problems

A number of six digits is written down at random. Probability that sum of digits of the number is even is

(A)1/2

(B) 3/8

(C) 3/7

(D) none of these

Sol. (A).

As we are considering all possible six digit numbers, half of these would have sum of their digits to be even and half of these would have sum of their digits to be odd. Hence the required probability would be 1/2.

Two small squares on a chess board are chosen at random. Probability that they have a common side is,

(A) 1/3

(B) 1/9

(C) 1/18

(D) none of these

Sol. (C)

There are 64 small squares on a chessboard.

⇒ Total number of ways to choose two squares = 64C2 = 32.63

For favourable ways we must choose two consecutive small squares for any row or any column. ⇒ Number of favourable ways = (7×8)×2

favourable ways = (7×8)×2 ⇒ Required probability = 7×8×2 ⁄ 32.63 = 1 ⁄ 18

3. Fifteen coupons are numbered 1, 2, 3, … 15. Seven coupons are selected at random one at a time with replacement. The probability that the largest number appearing on the selected coupon is 9, is

(A) (9⁄16)6

(B) (8⁄15)7

(C) (3⁄5)7

(D) none of these

Sol. (D) Total ways = 157

For favorable ways, we must have 7 coupons numbered from 1 to 9 so that '9' is selected at least once. Thus total number of favorable ways are, 97 – 87

⇒ Required probability = 97 – 87⁄157

4. A fair coin is tossed a fixed number of times. If the probability of getting 7 heads is equal to getting 9 heads, then the probability of getting 2 heads is,

(A) 15/28

(B) 2/15

(C) 15/213

(D) none of these

Sol. (C). Let coin be tossed 'n' times and X be the random variable representing the number of heads appearing in 'n' trials.

P(X = 7) = P(X = 9); ⇒ nC7(1/2)n-7 = nC9(1/2)n-9 × (1/2)9

⇒ nC7 = nC9 ⇒ n = 16; Now P(X = 2) = 16C2(1/2)2(1/2)14

= 16C2/216 = (16×15)/217 = 15/213.

5. If the papers of 4 students can be checked by any one of the 7 teachers, then the probability that all the 4 papers are checked by exactly 2 teachers is

(A) 2/7

(B) 32/343

(C) 12/49

(D) none of these

Sol. (D) Total number of ways in which 4 papers can be distributed among 7 teachers = 74

Now exactly 2 teachers out of 7 can be chosen in 7C2 ways. And total number of ways in which 4 papers can be given to these 2 teachers (each one getting at least one) = (24–2) =14

⇒ Total number of ways in which exactly 2 teachers check all four papers = 7C2 × 14 = 21 × 14

⇒ Required probability = 21 ⋅ 14 7 4 = 3 ⋅ 2 7 2 = 6 49 .

6. A bag contains 5 white and 3 black balls. 4 balls are successively drawn out and not replaced. The probability that they are alternately of different colours is

(A) 1/196

(B) 2/7

(C) 1/7

(D) 13/56

Sol. (C). Required probability

= P(WBWB) + P(BWBW)

= 5/8 x 3/7 x 4/6 x 2/5 + 3/8 x 5/7 x 2/6 x 4/5

= 1/7.

7. From a set of 100 cards numbered 1 to 100, one card is drawn at random. The probability that the number obtained on the card is divisible by 6 or 8 but not by 24 is

(A) 6/25

(B)1/4

(C) 1/6

(D) 1/5

Sol. (D). Let A: ‘’number is divisible by 6’’ and B: ‘’number is divisible by 8’’ then A ◠ B: ‘’number is divisible by 24’’.

⸫Required probability

= P(A OR B) – P(A ◠ B)

= P(A) + P(B) – P(A◠B) – P(A◠B)

=16/100+12/100-2(4/100)=20/100=1/5.

(Note that a number is divisible both by 6 and 8 iff it is divisible by L.C.M. of 6 and 8 i.e. 24. From 1 to 100, there are 16 multiples of 6, 12 multiples of 8 and 4 multiples of 24)

8. Statistics show that a specific disease is fatal in 10% cases. Find the probability that out of six patients in a hospital, only 3 will die is

(A) 1458 x 10-5

(B) 1458 x 10-6

(C) 41 x 10-6

(D) 8748 x 10-5

Sol. ( )It is a case of bernoullian trials where n = 6 and success may be defined as‘’ disease is fatal’’ so that

p=10/100=1/10 and q = 1 -1/10=9/10.

Required probability = P (3 successes)

=6C3p2q3 =20(1/10)3(9/10)3=14580/106 .