Understanding Straight Lines in Coordinate Geometry

Coordinate geometry bridges algebra and geometry, providing powerful tools to analyze geometric shapes through algebraic equations. The study of straight lines forms the foundation of analytical geometry, enabling precise mathematical descriptions of linear relationships in two-dimensional space. This comprehensive guide explores essential formulas and concepts for working with straight lines, from basic distance calculations to complex geometric constructions.

Core Concepts and Distance Relationships

The distance between two points A(x₁, y₁) and B(x₂, y₂) in a coordinate plane follows the Pythagorean theorem, expressed as AB = √[(x₁ - x₂)² + (y₁ - y₂)²]. This fundamental formula underpins numerous geometric calculations and serves as the basis for more advanced concepts in coordinate geometry.

The section formula provides coordinates for points dividing line segments in specific ratios. For internal division in ratio λ₁:λ₂, the dividing point P has coordinates ((λ₂x₁ + λ₁x₂)/(λ₂ + λ₁), (λ₂y₁ + λ₁y₂)/(λ₂ + λ₁)). External division follows a similar pattern with subtraction replacing addition in the denominator, yielding coordinates ((λ₂x₁ - λ₁x₂)/(λ₂ - λ₁), (λ₂y₁ - λ₁y₂)/(λ₂ - λ₁)).

Triangle Centers and Special Points

Triangles possess several remarkable centers, each with unique geometric properties and coordinate formulas. The centroid, where medians intersect, divides each median in a 2:1 ratio and has coordinates G = ((x₁ + x₂ + x₃)/3, (y₁ + y₂ + y₃)/3) for a triangle with vertices at (x₁, y₁), (x₂, y₂), and (x₃, y₃).

The orthocenter represents the intersection of altitudes, while the circumcenter marks where perpendicular bisectors meet. The incenter, found at the intersection of angle bisectors, has coordinates I = ((ax₁ + bx₂ + cx₃)/(a + b + c), (ay₁ + by₂ + cy₃)/(a + b + c)), where a, b, and c represent the lengths of sides opposite to the respective vertices.

Equations of Straight Lines

Straight lines can be represented through various equation forms, each suited to different problem-solving contexts. The general first-degree equation Ax + By + C = 0 represents any straight line, provided at least one coefficient is non-zero. The slope-intercept form y = mx + c immediately reveals the line's slope (m) and y-intercept (c), making it particularly useful for graphing and analyzing linear relationships.

The intercept form x/a + y/b = 1 elegantly expresses lines passing through specific intercepts on both axes. For lines characterized by their perpendicular distance from the origin, the normal form x cos α + y sin α = p provides a geometric interpretation where p represents the perpendicular distance and α indicates the angle this perpendicular makes with the positive x-axis.

Angular Relationships and Line Interactions

When two lines with slopes m₁ and m₂ intersect, the acute angle θ between them satisfies tan θ = |(m₁ - m₂)/(1 + m₁m₂)|. This formula reveals important special cases: parallel lines occur when m₁ = m₂, while perpendicular lines satisfy m₁m₂ = -1. These relationships enable quick identification of line orientations and facilitate construction of parallel and perpendicular lines.

The distance from a point P(x₁, y₁) to a line ax + by + c = 0 equals |ax₁ + by₁ + c|/√(a² + b²). This perpendicular distance formula proves invaluable in optimization problems and geometric constructions. For parallel lines ax + by + c₁ = 0 and ax + by + c₂ = 0, the separation distance simplifies to |c₁ - c₂|/√(a² + b²).

Comprehensive Formula Reference Table

| Formula Name | Mathematical Expression | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Distance Formula | AB = √[(x₁ - x₂)² + (y₁ - y₂)²] | Distance between points A(x₁, y₁) and B(x₂, y₂) |

| Section Formula (Internal) | P((λ₂x₁ + λ₁x₂)/(λ₂ + λ₁), (λ₂y₁ + λ₁y₂)/(λ₂ + λ₁)) | Point dividing AB internally in ratio λ₁:λ₂ |

| Centroid | G((x₁ + x₂ + x₃)/3, (y₁ + y₂ + y₃)/3) | Center of mass of triangle |

| Triangle Area | ½|x₁(y₂ - y₃) + x₂(y₃ - y₁) + x₃(y₁ - y₂)| | Area using vertex coordinates |

| Slope-Intercept Form | y = mx + c | Line with slope m and y-intercept c |

| Intercept Form | x/a + y/b = 1 | Line with x-intercept a and y-intercept b |

| Normal Form | x cos α + y sin α = p | Line at distance p from origin |

| Two-Point Form | (y - y₁) = [(y₂ - y₁)/(x₂ - x₁)](x - x₁) | Line through points (x₁, y₁) and (x₂, y₂) |

| Point-Line Distance | |ax₁ + by₁ + c|/√(a² + b²) | Perpendicular distance from point to line |

| Angle Between Lines | tan θ = |(m₁ - m₂)/(1 + m₁m₂)| | Acute angle between lines with slopes m₁, m₂ |

| Parallel Line Distance | |c₁ - c₂|/√(a² + b²) | Distance between parallel lines |

Advanced Applications and Problem-Solving

The concurrency condition for three lines requires their determinant to equal zero, providing an algebraic test for geometric configurations. When three lines a₁x + b₁y + c₁ = 0, a₂x + b₂y + c₂ = 0, and a₃x + b₃y + c₃ = 0 meet at a single point, the determinant formed by their coefficients vanishes.

Angle bisectors between two lines follow the principle of equal perpendicular distances. For lines a₁x + b₁y + c₁ = 0 and a₂x + b₂y + c₂ = 0, the bisector equations emerge from setting perpendicular distances equal, yielding two bisectors corresponding to acute and obtuse angles.

Understanding families of lines through intersection points enables elegant solutions to locus problems. The general equation L + λL' = 0 represents all lines passing through the intersection of L = 0 and L' = 0, with parameter λ determining the specific member of the family.

Distance Between Two Points

Let A and B be two given points, whose coordinates are given by A(x1, y1) and B(x2, y2) respectively. Then

AB = √[(x1 − x2)2 + (y1 − y2)2]

Section Formula

Coordinates of point P dividing the join of two points A(x1, y1) and B(x2, y2) internally in the given ratio λ1 : λ2 are

P ( ((λ2x1 + λ1x2) / (λ2 + λ1), (λ2y1 + λ1y2) / (λ2 + λ1) ) )

Coordinates of point P dividing the join of two points A(x1, y1) and B(x2, y2) externally in the ratio λ1 : λ2 are

P ( ((λ2x1 − λ1x2) / (λ2 − λ1), (λ2y1 − λ1y2) / (λ2 − λ1) ) )

Centroid

The point of concurrency of the medians of a triangle is called the centroid of the triangle. The centroid of a triangle divides each median in the ratio 2 : 1. The coordinates are given by

G ≡ ( (x1 + x2 + x3) / 3, y1 + y2 + y3) / 3 ) )

Orthocentre

The point of concurrency of the altitudes of a triangle is called the orthocentre of the triangle. The coordinates of the orthocentre of the triangle A(x₁, y₁), B(x₂, y₂), C(x₃, y₃) are ( (x₁ tan A + x₂ tan B + x₃ tan C) / (tan A + tan B + tan C), (y₁ tan A + y₂ tan B + y₃ tan C) / (tan A + tan B + tan C) ) .

Incentre

The point of concurrency of the internal bisectors of the angles of a triangle is called the incentre of the triangle. The coordinates of the in centre are given by I ≡ ( (a x₁ + b x₂ + c x₃) / (a + b + c), (a y₁ + b y₂ + c y₃) / (a + b + c) ) where a, b and c are lengths of the sides BC, CA and AB respectively.

Circumcentre

The point of concurrency of the perpendicular bisectors of the sides of a triangle is called the circumcentre of the triangle. The coordinates of the circumcentre of the triangle with vertices A(x₁, y₁), B(x₂, y₂), C(x₃, y₃) are ( (x₁ sin 2A + x₂ sin 2B + x₃ sin 2C) / (sin 2A + sin 2B + sin 2C), (y₁ sin 2A + y₂ sin 2B + y₃ sin 2C) / (sin 2A + sin 2B + sin 2C) ) .

Centroid divides the line joining orthocentre and circumcentre in 2 : 1 internally.

Area of a Triangle

Let (x1, y1), (x2, y2), and (x3, y3) respectively be the coordinates of the vertices A, B, C of a triangle ABC. Then the area of triangle ABC is:

(1/2) | x1(y2 – y3) + x2(y3 – y1) + x3(y1 – y2) | = Modulus of (1/2)

| x1 | y1 | 1 |

| x2 | y2 | 1 |

| x3 | y3 | 1 |

Exa.: The area of the triangle with vertices at (p–4, p+5), (p+3, p–2) and (p, p) is

(A) 3p + p2

(B) |p| + 5

(C) |p – 3|

(D) none of these

Solution: (D). The area of triangle is

| p–4 | p+5 | 1 |

| p+3 | p–2 | 1 |

| p | p | 1 |

= (1/2)

| –4 | 5 | 0 |

| 3 | –2 | 0 |

| p | p | 1 |

(R1 → R1 – R3, R2 → R2 – R3)

= |(1/2)(8–15)| = 7/2 sq. units,

which remains constant for all values of p.

Procedure for Finding the Equation of the Locus of a Point

- If we are finding the equation of the locus of a point P, assign coordinates (h, k) to P.

- Express the given conditions as equations in terms of the known quantities to facilitate calculations. We sometimes include some unknown quantities known as parameters.

- Eliminate the parameters, so that the eliminant contains only h, k and known quantities.

- Replace h by x, and k by y, in the eliminant. The resulting equation would be the equation of the locus of P.

- If x and y coordinates of the moving point are obtained in terms of a third variable t (called the parameter), eliminate t to obtain the relation in x and y and simplify this relation. This will give the required equation of locus.

Straight Line

Any equation of first degree of the form Ax + By + C = 0, where A, B, C are constants always represents a straight line (at least one out of A and B is non-zero).

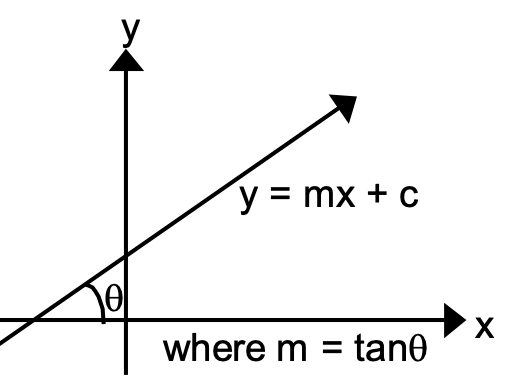

Slope

If θ is the angle at which a straight line is inclined to the positive direction of x axis, slope of the line is m = tanθ, 0 ≤ θ < 180° (θ ≠ 90°).

Standard Equations of Straight Lines

Slope Intercept Form

y = mx + c,

where m = slope of the line = tanq

c = y intercept

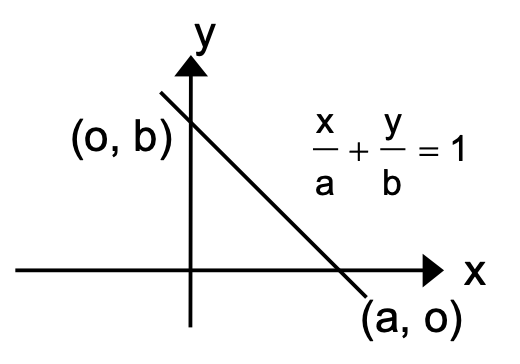

Intercept Form

x/a + y/b = 1

x intercept = a

y intercept = b

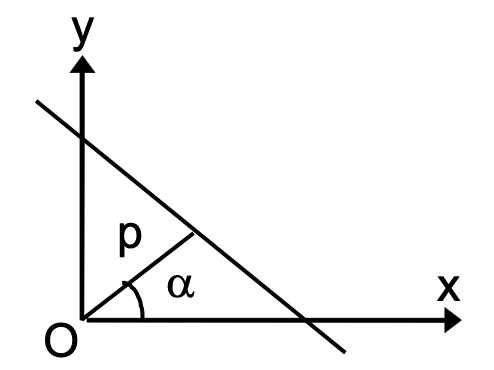

Normal Form

x cosa + y sina = p, where a is the angle which the perpendicular to the line makes with the axis of x and p is the length of the perpendicular from the origin to the line. p is always positive.

Slope Point Form

Equation: y - y1 = m(x - x1), where

(a) One point (x1, y1) on the straight line (x1, y1)

(b) The direction of the straight line i.e., the slope of the line = m

Two Point Form:

Equation: y − y1 = y2 − y1⁄x2 − x1 (x − x1) ,

where (x1, y1) and (x2, y2) are the two given points. Here m = y2 − y1⁄x2 − x1 .

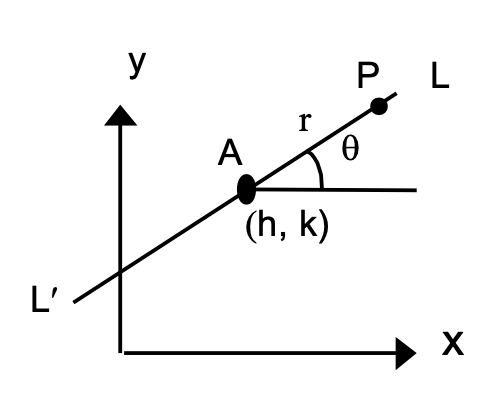

Parametric Form

To find the equation of a straight line which passes through a given point A(h, k) and makes a given angle θ, with the positive direction of the x-axis.

P(x, y) is any point on the line LAL′.

Let AP = r. x − h = r cosθ y − k = r sinθ

x − hcosθ=y − ksinθ=r is the equation of the straight line LAL′.

Any point on the line will be of the form (h + r cosθ, k + r sinθ) and for any value of r this will represent a point on the straight line. Here | r | gives the distance of the point P from the fixed point (h, k).

Position of Two Points with respect to a Given Line

Let the given line be ax + by + c = 0 and P(x1, y1), Q(x2, y2) be two points. If the quantities ax1 + by1 + c and ax2 + by2 + c have the same signs, then both the points P and Q lie on the same side of the line ax + by + c = 0.

If the quantities ax1 + by1 + c and ax2 + by2 + c have opposite signs, then they lie on the opposite sides of the line.

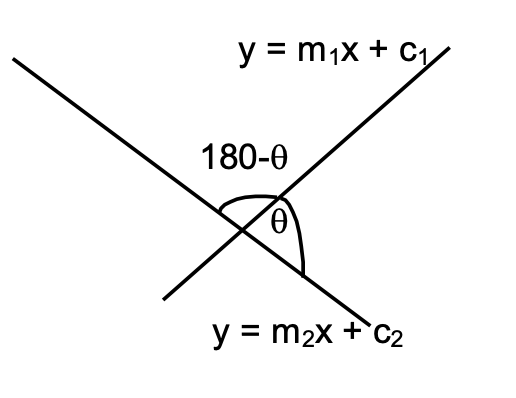

Angle between Two Straight Lines

If θ is the acute angle between two lines, then

where m1 and m2 are the slopes of the two lines and are finite.

Notes:

- If the two lines are perpendicular to each other then m1m2 = -1.

- Any line perpendicular to ax + by + c = 0 is of the form bx – ay + k = 0.

- If the two lines are parallel or are coincident, then m1 = m2.

- Any line parallel to ax + by + c = 0 is of the form ax + by + k = 0.

The Distance between Two Parallel Lines

The distance between two parallel lines:

ax + by + c₁ = 0 and ax + by + c₂ = 0 is

|c₁ − c₂|

√(a² + b²)

Length of the Perpendicular from a Point on a Line

The length of the perpendicular from P(x₁, y₁) on ax + by + c = 0 is

|ax₁ + by₁ + c|

√(a² + b²)

The Distance between Two Parallel Lines

The distance between two parallel lines:

ax + by + c₁ = 0 and ax + by + c₂ = 0 is

|c₁ − c₂|

√(a² + b²)

Length of the Perpendicular from a Point on a Line

The length of the perpendicular from P(x₁, y₁) on ax + by + c = 0 is

|ax₁ + by₁ + c|

√(a² + b²)

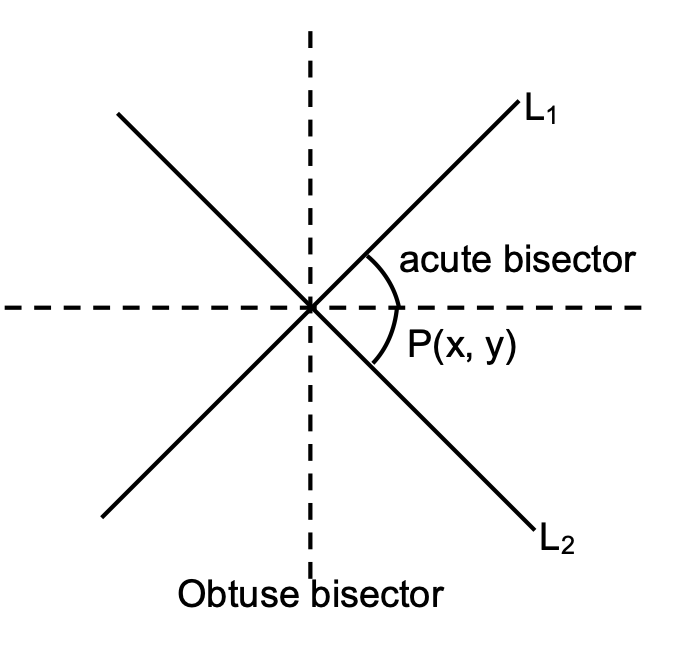

Equation of the Bisector of the Angles between Two Lines

Equation of the Bisector of the Angles between Two Lines

Consider two lines L1 and L2 represented as:

L1 ≡ a1x + b1y + c1 = 0

and L2 ≡ a2x + b2y + c2 = 0.

Let P (x, y) be any point on either of bisectors.

Perpendicular distance of P from L1 = Perpendicular distance of P from L2

Taking c1 > 0, c2 > 0 and (a1b2 ≠ a2b1)

| Conditions | Acute angle bisector | Obtuse angle bisector |

|---|---|---|

| A1a2 + b1b2 > 0 | − | + |

| A1a2 + b1b2 < 0 | + | − |

FAMILY OF LINES

The general equation of the family of lines through the point of intersection of two given lines is

L + lL¢ = 0, where L = 0 and L¢ = 0 are the two given lines, and l is a parameter. Conversely any line of the form L1 + l L2 = 0 passes through a fixed point which is the point of intersection of the lines L1 = 0 and L2 = 0.

Concurrency of Straight Lines

The condition for three lines a₁x + b₁y + c₁ = 0, a₂x + b₂y + c₂ = 0, a₃x + b₃y + c₃ = 0 to be concurrent is

-

a₁ b₁ c₁

a₂ b₂ c₂

a₃ b₃ c₃ = 0 - There exist three constants l, m, n (not all zero at the same time) such that

lL₁ + mL₂ + nL₃ = 0, where L₁ = 0, L₂ = 0, and L₃ = 0 are the three given straight lines. - The three lines are concurrent if any one of the lines passes through the point of intersection of the other two lines.

Pair of Straight Lines

The general equation of second degree ax2 + 2hxy + by2 + 2gx + 2fy + c = 0 represents a pair of straight lines if abc + 2fgh − af2 − bg2 − ch2 = 0 and h2 ≥ ab.

The homogeneous second degree equation ax2 + 2hxy + by2 = 0 represents a pair of straight lines through the origin if h2 ≥ ab.

m₁ + m₂ = −2h/b, m₁m₂ = a/b

If θ be the angle between two lines, through the origin, then

tan θ = ± √(m1 + m2)2 − 4m1m2

1 + m1m2 = ± 2√h2 − ab

a + b .

The lines are perpendicular if a + b = 0 and coincident if h2 = ab.

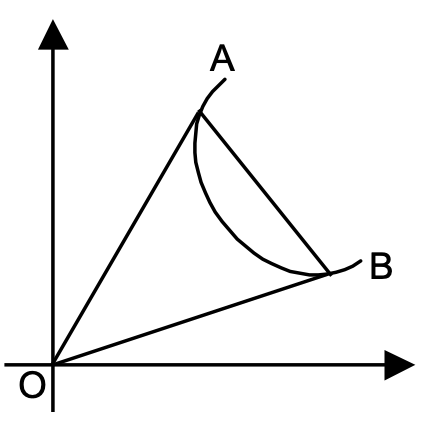

Joint Equation of Pair of Lines joining the Origin and Points of Intersection of a Curve and a Line:

If the line lx + my + n = 0, ((n ≠ 0) i.e., the line does not pass through origin) cut the curve ax² + 2hxy + by² + 2gx + 2fy + c = 0 at two points A and B, then the joint equation of straight lines passing through A and B and the origin is given by homogenizing the equation of the curve by the equation of the line. i.e.,

ax² + 2hxy + by² + (2gx + 2fy) ( (lx + my)/-n ) + c ( (lx + my)/-n )2 = 0

is the equation of the lines OA and OB.

Expert of straight line geometry in coordinate systems provides essential tools for mathematical modeling, engineering applications, and advanced geometric analysis. These formulas and concepts form the foundation for understanding curves, transformations, and higher-dimensional geometry. Regular practice with these relationships develops spatial reasoning and algebraic manipulation skills crucial for mathematics and technical fields.