The Fundamental Nature of Momentum and Its Physical Significance

Momentum represents one of the most fundamental quantities in physics, embodying the very essence of motion itself. When we define momentum as the product of mass and velocity (P = mv), we're capturing something profound about how objects interact with the world around them. A massive truck moving slowly can have the same momentum as a small car moving rapidly, demonstrating that momentum depends equally on how much matter is moving and how fast it's moving. This concept becomes particularly important when we consider that momentum is a vector quantity, meaning it has both magnitude and direction. The vectorial nature of momentum is crucial in understanding collision dynamics, where the direction of motion after impact depends not just on the speeds involved, but on the precise directional components of the momenta before collision. In the SI system, momentum is measured in kg-m/s, which elegantly combines the fundamental units of mass and velocity, while its dimensional analysis as MLT⁻¹ reveals its deep connection to the basic quantities of mechanics.

Centre of Mass: The Mathematical Heart of Systematic Motion

The concept of centre of mass provides a powerful mathematical tool for simplifying complex multi-body systems into manageable calculations. When we define the centre of mass as the point where the entire mass of a system can be considered concentrated, we're essentially creating a representative point that captures the average position of all the mass in the system, weighted by the actual mass distribution. For a system of discrete particles, the centre of mass coordinates are calculated using xcm = (Σmixi)/Σmi, which represents a mass-weighted average of all particle positions. This mathematical formulation becomes particularly elegant when extended to continuous mass distributions, where we replace discrete sums with integrals over infinitesimal mass elements. The physical significance of the centre of mass becomes apparent when we realize that external forces act on the system as if all the mass were concentrated at this single point. This principle dramatically simplifies the analysis of complex systems, allowing us to treat a spinning, tumbling object as a single particle located at its centre of mass when analyzing its translational motion.

The Profound Implications of Momentum Conservation

The principle of conservation of momentum stands as one of the most fundamental laws in physics, stemming directly from Newton's third law and the symmetry properties of space and time. When no external forces act on a system, the total momentum remains constant, which mathematically translates to Σpi(initial) = Σpi(final). This conservation principle has far-reaching implications that extend beyond simple collision problems. In rocket propulsion, for instance, the conservation of momentum explains how spacecraft can accelerate in the vacuum of space by expelling mass in the opposite direction to their desired motion. The rocket equation, vf - vi = -vrel ln(Mf/M0), emerges directly from momentum conservation and reveals the logarithmic relationship between mass ratio and velocity change. This same principle governs phenomena ranging from the recoil of firearms to the motion of astronomical bodies. When we observe the conservation of momentum in action, we're witnessing a fundamental symmetry of nature – the idea that the laws of physics remain unchanged regardless of our location in space, a principle known as translational symmetry.

Impulse and the Time-Dependent Nature of Force

The concept of impulse bridges the gap between force and momentum, revealing how forces acting over time intervals produce changes in motion. Defined as J = F·Δt = Δp, impulse represents the cumulative effect of a force acting over a specific time period. This relationship, known as the impulse-momentum theorem, provides crucial insights into collision dynamics and explains why airbags in automobiles are so effective at reducing injury. By extending the time over which a collision occurs, airbags reduce the average force experienced by passengers while maintaining the same total impulse. The mathematical formulation of impulse as the integral of force over time, J = ∫F dt, reveals that even if we don't know the exact force function during a collision, we can still determine the momentum change by calculating the area under the force-time curve. This principle finds applications in sports, where follow-through techniques increase the time of contact and thus the impulse delivered to balls or projectiles.

Collision Dynamics and Energy Considerations

Collisions represent perhaps the most dramatic demonstrations of momentum conservation, where the interplay between momentum and energy conservation creates a rich variety of physical phenomena. In elastic collisions, both momentum and kinetic energy are conserved, leading to specific mathematical relationships for the final velocities: v1 = [(m1-m2)u1 + 2m2u2]/(m1+m2) and v2 = [(m2-m1)u2 + 2m1u1]/(m1+m2). These equations reveal fascinating special cases, such as the complete velocity exchange that occurs when two objects of equal mass collide elastically. The coefficient of restitution, e = (relative velocity of separation)/(relative velocity of approach), provides a measure of how "bouncy" a collision is, ranging from e = 1 for perfectly elastic collisions to e = 0 for perfectly inelastic collisions where objects stick together. The loss of kinetic energy in inelastic collisions, given by ΔKE = ½(m1m2)/(m1+m2)²(1-e²), demonstrates how mechanical energy can be converted to other forms like heat, sound, and deformation energy while momentum remains conserved. This interplay between momentum conservation and energy transformation underlies many practical applications, from the design of crumple zones in vehicles to the analysis of particle interactions in high-energy physics experiments.

1. Momentum

Definition: Momentum is the quantity of motion contained in a body, measured by the product of mass and velocity.

Formula: P = m·v

- Units: kg-m/s (SI), gram-cm/s (CGS)

- Dimensions: MLT⁻¹

2. Centre of Mass

Definition: The point where the entire mass of a body can be considered concentrated, behaving similarly to external forces as the whole body would.

For discrete particles:

- xcm = (m₁x₁ + m₂x₂ + ... + mₙxₙ)/(m₁ + m₂ + ... + mₙ)

- Similar expressions for ycm and zcm

Key principle: In a uniform gravitational field, centre of mass and centre of gravity coincide.

3. Motion of Centre of Mass

Velocity of centre of mass: vcm = (m₁v₁ + m₂v₂ + ... + mₙvₙ)/(m₁ + m₂ + ... + mₙ)

Acceleration of centre of mass: acm = ΣFext/M

Important note: In the absence of external forces, the centre of mass either remains at rest or moves with uniform velocity.

4. Conservation of Linear Momentum

Principle: When no external force acts on a system, the total momentum remains constant.

Mathematical expression: If ΣFext = 0, then P₁ + P₂ + ... + Pₙ = constant

Applications:

- Gun-bullet recoil problems

- Collision analysis

- Rocket propulsion

5. Impulse

Definition: The product of net force and time interval over which it acts.

Formula: J = F·Δt = Δp (change in momentum)

Impulse-momentum theorem: The change in momentum equals the impulse delivered.

6. Rocket Equation

For a rocket in space with no external forces: Tsiolkovsky equation: vf - vi = -vrel ln(Mf/M₀)

Where:

- vrel = exhaust velocity relative to rocket

- M₀ = initial mass

- Mf = final mass

7. Collisions

Types of Collisions:

A. Elastic Collisions (e = 1):

- Both momentum and kinetic energy are conserved

- Velocities after collision:

- v₁ = [(m₁-m₂)u₁ + 2m₂u₂]/(m₁+m₂)

- v₂ = [(m₂-m₁)u₂ + 2m₁u₁]/(m₁+m₂)

B. Inelastic Collisions (e < 1):

- Only momentum is conserved

- Kinetic energy is not conserved

C. Perfectly Inelastic Collisions (e = 0):

- Objects stick together after collision

- v₁ = v₂ = (m₁u₁ + m₂u₂)/(m₁ + m₂)

Coefficient of Restitution:

e = (relative velocity of separation)/(relative velocity of approach) e = (v₂ - v₁)/(u₁ - u₂)

8. Special Cases in Elastic Collisions

-

Equal masses (m₁ = m₂): Velocities exchange

- Target at rest (u₂ = 0):

- Light projectile, heavy target: v₁ ≈ -u₁, v₂ ≈ 0

- Heavy projectile, light target: v₁ ≈ u₁, v₂ ≈ 2u₁

9. Two-Dimensional Collisions

For oblique collisions:

- Apply conservation of momentum in both x and y directions

- Use energy conservation for elastic collisions

- Consider coefficient of restitution along the line of impact

10. Key Formulas Summary

-

Momentum: P = mv

- Centre of mass velocity: vcm = (Σmᵢvᵢ)/Σmᵢ

- Conservation of momentum: Σpᵢnitial = Σpfinal

- Impulse: J = FΔt = Δp

- Coefficient of restitution: e = (separation velocity)/(approach velocity)

- Loss in kinetic energy: ΔKE = ½(m₁m₂)/(m₁+m₂)²(1-e²)

11. Important Applications

- Ballistic pendulum

- Rocket propulsion

- Recoil problems

- Nuclear reactions

- Sports (collision of balls)

- Traffic accident analysis

Momentum & Center of Mass

Understand the fundamental concepts, definitions, and mathematical formulations that form the foundation of momentum physics.

Conservation Laws

Master the principle of momentum conservation with detailed derivations, examples, and real-world applications.

Impulse & Collisions

Learn about impulse-momentum theorem, elastic and inelastic collisions, and coefficient of restitution with solved examples.

Advanced Applications

Explore rocket propulsion, two-dimensional collisions, and complex problem-solving techniques for competitive exams.

Momentum and Centre of Mass

Momentum

It is defined as the quantity of motion contained in a body and is measured by the product of mass and velocity.

Momentum P = m·v

The unit of momentum is kg·m/s in SI System and gram cm/s in CGS system.

Its dimension is MLT-1.

Centre of Mass

The centre of mass of an object is defined as the point where whole mass of the body may be supposed to be concentrated and the point mass behaves similarly to an external force as the whole body would have behaved.

If the system is considered to be composed of tiny masses m₁, m₂ and so on, at co-ordinates (x₁, y₁, z₁), (x₂, y₂, z₂) and so on, then the co-ordinates of the centre of mass are given by:

xcm = ∑ ximi / ∑ mi, ycm = ∑ yimi / ∑ mi, zcm = ∑ zimi / ∑ mi

Where the sums extend over all masses composing the object. In a uniform gravitational field, the centre of mass and the centre of gravity coincide.

The position vector rcm of the centre of mass can be expressed in terms of the position vector r1, r2, ... of the particles as

rcm = (m₁r1 + m₂r2 + ⋯ ) / (m₁ + m₂ + ⋯ ) = ∑ miri / ∑ mi

In statistical language the centre of mass is a mass-weighted average of the particles.

Centre of Mass of a body having continuous distribution of mass

If the bodies given are not discrete and their distances are not specific, the centre of mass can be found out by taking an infinitely small part of mass dm at a distance x and y from the origin of

the chosen co-ordinate system.

Xcm = ∫ x dm/ ∫ dm ; Ycm = ∫ y dm / ∫ dm ; Zcm = ∫ z dm/ ∫ dm

In vector form 𝔩cm = ∫ 𝔩 dm/ ∫ dm

They are as follows

- Semi-circular Disc at 4/3\pi R from the straight edge.

- Hemispherical Shell at R/2 from the plane surface.

- Solid Hemisphere at 3/8 R from the plane surface. (Where R is the radius)

- Solid cone at h/4 from the plane surface. (where h is the height of the cone)

- Solid Hollow cone h/3 from the plane surface.

Motion of the Centre of Mass of a System of Particles

Position vector of the centre of mass of a system of particle is given by

Rcm = m1r1 + m2r2 + .......... + mnrn / m1 + m2 + .................. + mn

Differentiating both sides with respect to time, we obtain

dRcm / dt = m1 dr1/dt + m2 dr2/dt + .......... + mn drn/dt / m1 + m2 + m3 + ....... + mn

∴ The velocity of the center of mass of the system is given by

vcm = m1v1 + m2v2 + .......... + mnvn / m1 + m2 + .................. + mn

Differentiating both sides with respect to time, we obtain

dvcm/dt = m1 dv1/dt + m2 dv2/dt + .......... + mn dvn/dt / m1 + m2 + .......... + mn

∴ Acceleration of the c.m. of a system of particles.

⇒ acm = F1 + F2 + .......... + Fn / M = ΣFext / M ⇒ac.m. = ΣFext / M

If ΣFext = 0, acm = 0

NOTE: Hence in absence of any external force centre of mass of a system of particles is either at rest or in uniform motion on a straight line.

Conservation of Linear Momentum of the System of Particles

Since m₁ d⃗v₁/dt + m₂ dv₂/dt + ………… + mₙ d⃗vₙ/dt = M⃗acm

⇒ d/dt (m₁v₁ + m₂v₂ + ……… + mₙvₙ) = Σ⃗Fext

⇒ d/dt (⃗p₁ + ⃗p₂ + ……… + ⃗pₙ) = Σ⃗Fext

Where ⃗p₁, ⃗p₂, ……… and ⃗pₙ are the linear momenta of the particles?

If Σ⃗ Fext = 0

⃗p₁ + ⃗p₂ + ……… + ⃗pₙ = Constant.

Hence, in absence of any external force total momentum of a system of particles remain constant.

Impulse

The impulse of the net force, denoted by ̅J, is defined to be the product of the net force and the time interval under consideration.

̅J = ∑̅F (t2 - t1) = ∑̅F Δt (Assuming constant net force)

To see what impulse is good for, let's go back to Newton's second law as stated in terms of momentum i.e.

∑̅F = d̅P / dt

If the net force ∑̅F is constant, then d̅P/dt is also constant.

In that case, d̅P/dt is equal to the total change in momentum (̅P2 – ̅P1) during the time interval (t2 – t1), divided by the interval

∑̅F = ̅P2 – ̅P1 / t2 – t1

∴ ∑̅F (t2 – t1) = ̅P2 – ̅P1

∴ ̅J = ̅P2 – ̅P1

The change in momentum of a body during a time interval equal to the impulse of the net force that acts on the body during that interval in the direction of the change in momentum.

∑F = dP

dt

∴ t2∫t1 ∑Fdt = t2∫t1dP dt = P2∫P1 dp = P2 − P1.

The integral on the left is defined to the impulse J of the net force ∑F during this interval.

J = t2∫t1 ∑Fdt

We can define an average net force Fav such that even when ∑F is not constant, the impulse J is given by

J = ∑Fav (t2 − t1).

∑Fav

is called the impulsive force, which is very great force acting for a very small interval of time.

Rocket Equation

In distant space Fext = 0 and of dvdt is in positive direction, the direction of vrel is negative. Now M dvdt = − vrel dMdt

⇒dv = − vrel dMM

If the original mass of the rocket at t = 0 was M0 and mass of the fuel burned is m, then.

∫vfvi dv = − vrel ∫M0 − mM0dMM ⇒ vf − vi = − vrel ln M0 − mM0

Mf = M0 e− vf / vrel where Mf = M0 − m

Collisions

When bodies interact strongly for a very short time, with or without coming in actual contact, collision is said to take place.

When two bodies like a car and a truck or a cricket ball and a bat, or even two subatomic particle like a proton and a neutron collide, something very different happens as compared to, say a body that’s falling freely under gravity. In both cases, there are forces that act on the bodies (or particles) but the effects are different.

For body falling freely under gravity, the weight of the body causes it to accelerate and the velocity (if it’s falling down) and the momentum increases gradually.

On the other hand, in a collision, the change in velocity isn’t gradual, it’s sudden (abrupt). Since, a finite change in velocity occurs in a very small time interval during which the bodies come in contact. The forces of action and reaction between the colliding bodies is extremely large so much so that all other forces (except some contact forces) acting on these colliding bodies during this time interval can be neglected in comparison.

Thus, in the study of collisions, we’re going to study the effect of these forces of collisions acting between these bodies (or, particles).

(a) Since the forces of collision between two bodies (or particles) are internal forces to the system consisting of two bodies, and all other forces are to be neglected, the net linear momentum of the system remains conserved during the collision. So is the net angular momentum of the system.

(b) The other law that we can use to predict the effect of collisions is what is known as Newton’s Experimental Law of collisions: when two bodies collide, the relative velocity of separation of the two bodies, perpendicular to the surface of contact, is proportional to relative velocity of approach of the two bodies (also perpendicular to the surface of contact). The constant of proportionality (represented by e) depends only on the material of the bodies and is known as the coefficient of restitution.

If two bodies move with velocity u1 and u2 to change the velocity to v1 and v2 after collision. Then the coefficient of restitution

Coefficient of Restitution – Formula

− e = v2 − v1 /u2 − u1

or e = v2 − v1 /v1 − v2 = relative velocity of separation / relative velocity of approach

Collisions: Elastic & Inelastic collisions

Collisions can, in general, be classified as elastic or inelastic collisions.

In an elastic collision, the coefficient of restitution, e = 1 and in it the momentum as well as the kinetic energy of the system of colliding bodies remains conserved.

In inelastic collisions, e < 1. In this type of collision, only momentum remains conserved. The kinetic energy doesn’t remain conserved.

For a perfectly inelastic collision, e = 0. Here the momentum remains conserved but kinetic energy doesn’t. the colliding bodies stick together.

For normal bodies, 0 < e < 1

Velocities of Colliding Bodies after Collision

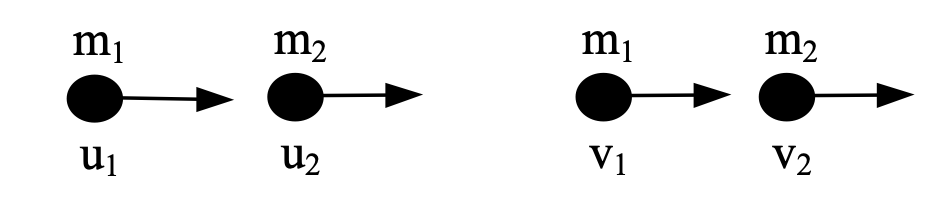

Let there be two bodies with mass m1 and m2 moving with velocity u1 and u2. They collide at an instant and acquire velocity v1 and v2 after collision. Let the coefficient of restitution of the colliding bodies be e. Then, applying Newton’s experimental law and the law of conservation of momentum we can find the value of velocities v1 and v2.

Conserving momentum of the colliding bodies before and after the collision

m1u1 + m2u2 = m1v1 + m2v2… (i)

Applying Newton’s experimental law

We have v2 − v1 / u2 − u1 = −e

v2 = v1 − e (u2 − u1) … (ii)

Putting (ii) in (i) we obtain

m1u1 + m2u2 = m1v1 + m2{ v1 − e (u2 − u1) }

v1 = u1 (m1 − e m2) / m1 + m2 + u2 m2(1 + e) / m1 + m2… (iii)

From (ii)

v2 = v1 − e (u2 − u1)

v2 = u1 m1(1 + e) / m1 + m2 + u2 (m2 − m1e) / m1 + m2 (4)

When the collision is elastic; e = 1

Finally,

v1 = m1 − m2 / m1 + m2 u1 + 2m2m1 + m2u2v2 = 2m1m1 + m2u1 + m2 − m1m1 + m2u2

(i) If m1 = m2

v1 = u2andv2 = u1

When the two bodies of equal mass collide head on elastically, their velocities are mutually exchanged.

(ii) If m1 = m2 and u2 = 0, then

v1 = 0, v2 = u1

(iii) If target particle is massive;m2 »» m1andu2 = 0

v1 = −u1and v2 = 0

The light particle recoils with same speed while the heavy target remains practically at rest.

If u2 ≠ 0, then v1 ≈ −u1 + 2u2and v2 ≈ u2

v1 = u1 and v2 = 2u1 − u2

If the target is initially at rest, u2 = 0

v1 = u1 and v2 = 2u1

The motion of heavy particle is unaffected, while the light target moves apart at a speed twice that of the particle.

v1 = v2 = u1 m1/m1 + m2 + u2 m2/m1 + m2

= u1 m1 + u2 m2/m1 + m2

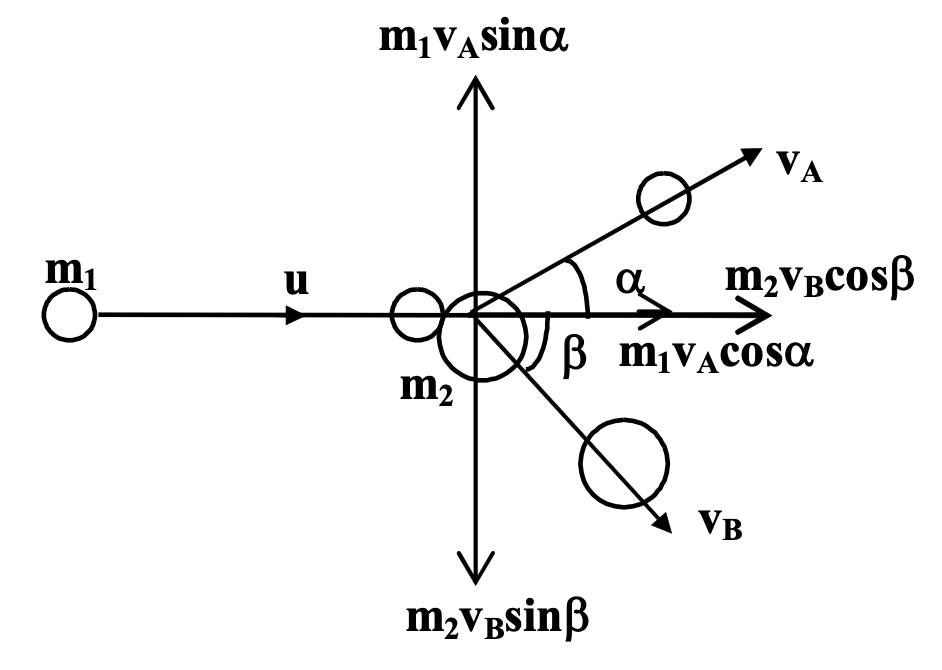

Elastic Collision between particles in two Dimensions

Consider a particle A projectile that approaches another particle B (target) with initial velocity u. After the collision, the final velocities are vA and vB respectively w.r.t. the initial direction of u (taken as the x-axis here).

We can write,

m1u = m1 vA cos α + m2 vB cos β

Elastic Collision Equations

0 = m1 vA sin α − m2 vB sin β . . . (1) (conservation of momentum)

since the collision is elastic, the total energy is conserved,

12 m1u12 = 12 m1vA2 + 12 m2vB2 . . . (2)

These three equations are sufficient to determine the unknowns, provided one of the angle say α is known.