Understanding Units, Dimensions & Vectors: A Comprehensive Physics Guide

The Foundation of Physics: Units and Dimensional Analysis

Units, dimensions, and vectors form the cornerstone of physics education and are essential concepts that every student must master to excel in physics problem-solving. The systematic approach to measuring physical quantities begins with understanding fundamental units—the basic building blocks from which all other measurements derive. In the internationally accepted SI (Système International) system, seven fundamental quantities serve as the foundation: mass (kilogram), length (meter), time (second), temperature (Kelvin), electric current (Ampere), luminous intensity (Candela), and quantity of matter (mole). These fundamental units combine mathematically to create derived units for complex physical quantities like velocity, acceleration, force, and energy.

Dimensional analysis represents one of the most powerful problem-solving tools in physics, offering multiple practical applications that extend far beyond academic exercises. This technique enables physicists and students to convert units between different measurement systems, verify the mathematical correctness of equations, and derive new relationships between physical quantities. The dimensional formula of any physical quantity expresses the powers to which fundamental units must be raised to represent that quantity. For instance, velocity has dimensions [LT⁻¹], acceleration has [LT⁻²], and force has [MLT⁻²]. Understanding these relationships allows students to check their work systematically and catch calculation errors before they compound into incorrect final answers.

Vector Mathematics: Essential Tools for Physics Problem-Solving

Vector quantities differ fundamentally from scalar quantities by possessing both magnitude and direction, making them indispensable for describing motion, forces, and fields in physics. Unlike scalars such as temperature, mass, or speed, vectors like displacement, velocity, acceleration, and force require careful consideration of their directional components. The mathematical operations involving vectors—addition, subtraction, and multiplication—follow specific rules that differ from ordinary arithmetic, requiring students to master techniques like the triangle law, parallelogram law, and component resolution methods.

Vector addition using rectangular components represents the most efficient method for solving complex physics problems involving multiple forces or displacements. This systematic approach involves resolving each vector into perpendicular x, y, and z components, adding corresponding components algebraically, and then calculating the resultant vector's magnitude and direction. The dot product (scalar product) and cross product (vector product) serve distinct purposes in physics applications: dot products calculate work done by forces, determine angles between vectors, and find vector projections, while cross products determine torques, magnetic forces, and areas of parallelograms formed by vectors.

Practical Applications and Problem-Solving Strategies

The practical significance of mastering units, dimensions, and vectors extends across all branches of physics, from basic mechanics to advanced quantum mechanics and electromagnetic theory. In mechanics problems, dimensional analysis helps students quickly identify whether their calculated answers are physically reasonable—a velocity result with dimensions of force clearly indicates an error. Vector analysis becomes crucial when analyzing motion in multiple dimensions, equilibrium of forces, rotational dynamics, and wave phenomena. Students preparing for competitive examinations like JEE, NEET, or AP Physics must develop fluency in these concepts to solve complex problems efficiently within time constraints.

Modern physics applications increasingly rely on vector mathematics for describing quantum states, electromagnetic fields, and relativistic effects. Understanding position vectors, displacement vectors, and their relationships enables students to analyze particle trajectories, orbital mechanics, and wave propagation. The cross product's role in determining magnetic forces and the dot product's application in calculating work and power demonstrate how these mathematical tools translate directly into physical understanding. Students who invest time in thoroughly understanding these fundamental concepts develop the mathematical foundation necessary for advanced physics courses and research applications, making units, dimensions, and vectors not just academic requirements but essential tools for scientific literacy and problem-solving across STEM fields.

FUNDAMENTAL AND DERIVED UNITS

As the number of physical quantities to be measured is very large, it is not feasible to define a separate unit for each quantity. To simplify these things we make use of relation between different physical quantities.

Derived Unites

In mechanics we treat length, mass and time as basic or fundamental quantities.

The units of all other physical quantities, which can be obtained from fundamental units, are called derived unit.

SYSTEM OF UNITS

Some common system of units used in mechanics are given below

|

Name of System |

Fundamental unit of |

||

|

Length |

Mass |

Time |

|

|

F.P.S. |

Foot |

Pound |

Second |

|

C.G.S |

Centimeter |

Gram |

Second |

|

M.K.S. (SI System) |

Meter |

Kilogram |

Second |

In physics SI system is based on seven fundamental and two derived unit.

|

Sl. No. |

Fundamental unit of Basic Physical Quantity |

Fundamental Unit |

Symbol Used |

|

1. |

Mass |

Kilogram |

kg |

|

2. |

Length |

Meter |

m |

|

3. |

Time |

Second |

s |

|

4. |

Temperature |

Kelvin |

K |

|

5. |

Electric current |

Ampere |

A |

|

6. |

Luminous intensity |

Candela |

cd |

|

7. |

Quantity of matter |

Mole |

mol |

|

S. |

Fundamental unit of Supplementary Physical Quantity |

Supplementary unit |

Symbol |

|

1. |

Plane angle |

Radian |

rad |

|

2. |

Solid Angle |

Steradian |

sr |

Prefixes to the power of 10

The physical quantities whose magnitude is either too large or too small can be expressed more compactly by the use of certain prefixes.

DIMENSIONAL ANALYSIS

Dimensions of a physical quantities is defined the power to which the fundamental units have to be raised to represent a derived units.

Uses of Dimensional equations

(i) Conversion of unit from one system to another.

(ii) Checking the accuracy of various formulae.

(iii) Derivation of formula

VECTORS AND SCALARS

The quantities which have magnitude only are called scalar quantities or simply scalars. On the other hands, quantities having both magnitude as well as direction are called vector quantities or simply vectors.

A vector can be represented by a single letter or two letters with an arrow head on it. For example force vector can be represented by , velocity vector can be represented by etc.

Note: If is A vector, its magnitude is represented by vector A or A.

POLAR OR AXIAL VECTORS

- Polar vectors: The vectors having a starting point or a point of application are called polar vectors. Displacement, force, velocity etc. are the examples of polar vectors.

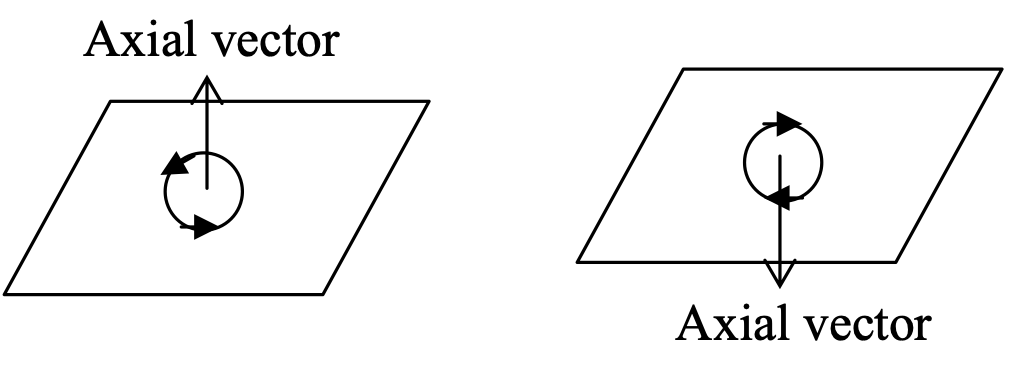

- Axial vectors: Vectors like angular acceleration, torque, angular velocity etc. represent rotational effects. The direction of such vectors is taken along the axis of rotation with the help of right hand screw rule. Such vectors are called axial vectors.

Directions of axial vectors having anticlockwise or clockwise rotational effects are shown in the adjoining figure.

Terms related to vectors

- Unit vector: A unit vector is a vector having unit magnitude and a definite direction. If vector A is a vector, then a unit vector in the direction of vector A can be given by the vector A divided by its magnitude. It is represented by a cap (^) on the vector (i.e., Â ) instead of an arrow. Then:

= →A / |A| or →A = AÂ

- Equal vectors: Two vectors are said to be equal if they have equal magnitude and same direction.

- Negative of a vector: Negative of a vector is the vector of same magnitude but acting in a direction opposite to that of the given vector. If →A be any arbitrary vector, then the negative vector of →A is represented by -→A.

- Parallel vectors:Two or more vectors, of equal or unequal magnitude are said to be in same direction.

vector A → B → Vector A → →B →

Note: If vectors act in parallel lines in opposite direction, they are called antiparallel vectors. →A → ← →B

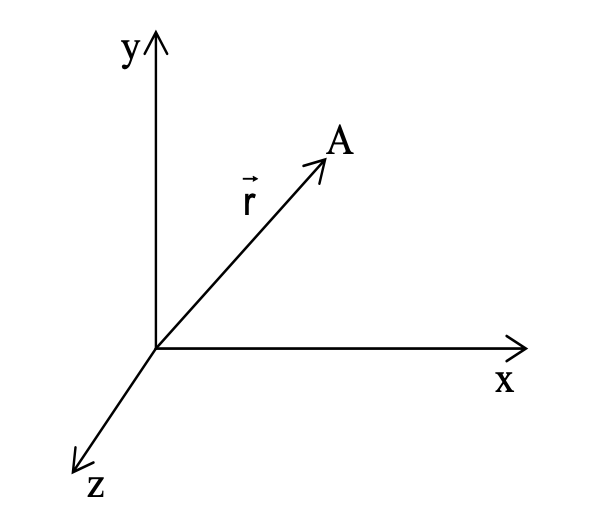

POSITION VECTOR

Consider an object is in motion with origin at O. If at any time, the object is at position A, then a vector with tail at O and head at A is called position vector of A and is represented by vector OA or vector r .The position vector of an object provides two important information about the objects i.e.

Position Vector

i) It gives the straight line distance of the object from the origin.

ii) It gives the direction of the position of the object with respect to the origin.

If A(x,y,z) be the position of the particle, the position vector of A (i.e. →OA) can be given by

→OA = xî + yĵ + z&kcirc; where î, ĵ and &kcirc; are unit vectors along x, y and z-directions respectively.

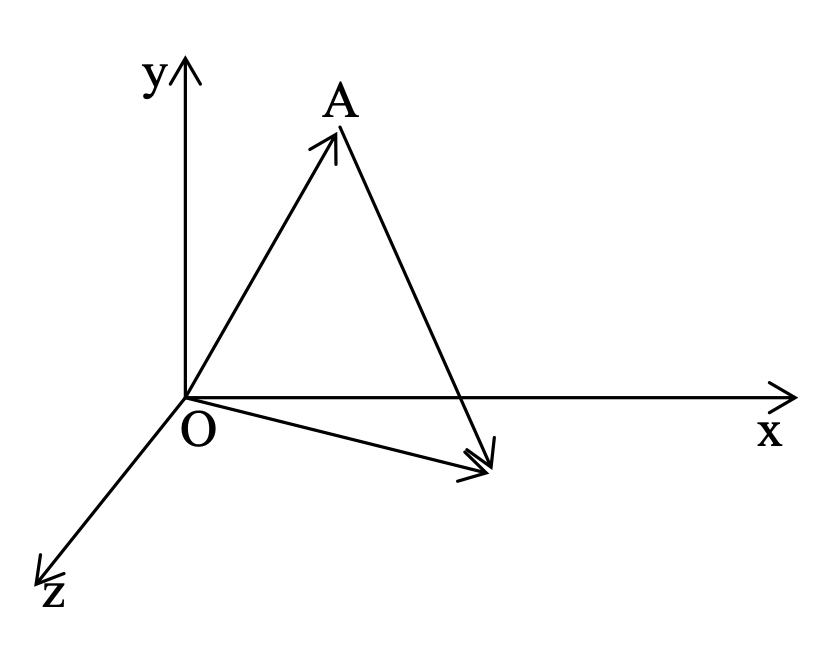

Displacement Vector

Consider at any time t1, a particle is at position A with position vector = x1 î + y1 ĵ + z1 k̂. Now, let at time t2, the particle reaches position B with position vector = x2 î + y2 ĵ + z2 k̂, then a vector with tail at A and head at B gives the displacement covered by the particle in the time interval (t2 − t1) and is called the displacement vector.

Hence we can define the displacement vector as the vector which determines how much and in which direction the object has changed its position in a given interval of time.

If OA̅ and OB̅ are the position vectors of A and B respectively, then the displacement vector for the particle can be given by

AB̅ = OB̅ − OA̅ or AB̅ = (x2 − x1) î + (y2 − y1) ĵ + (z2 − z1) k̂

Sketch of axes with origin O, point A in the first quadrant, and vector from A to a point near the x-axis. O y x z A O, point A, and the displacement vector AB̅.

Note:

- (x2 − x1), (y2 − y1) and (z2 − z1) are the components of the displacement vector in the x, y and z directions respectively.

- For any vector A̅ = x î + y ĵ + z k̂, |A̅| = √(x² + y² + z²).

Multiplication of a vector by a scalar:

When a vector →A is multiplied by a scalar n, the result obtained is a vector of magnitude n times the magnitude of →A and in the direction of →A i.e.

|n→A| = n|→A|

Note:

- If n is negative then the vector n→A has a direction opposite to that of →A.

- If →A is a unit vector, then the magnitude of n→A is n.

Addition of Vectors

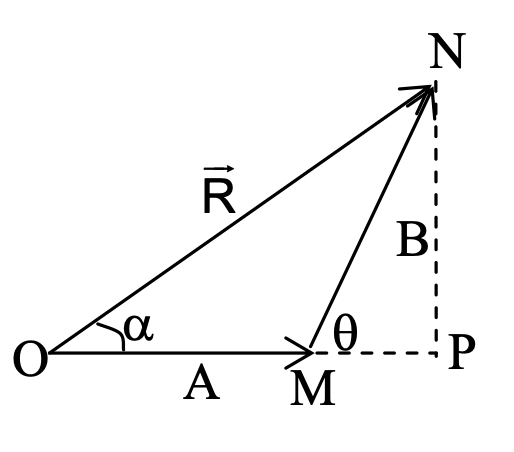

1. Triangle Law:

If two vectors acting on a particle at the same time are represented in magnitude and direction by the two sides of a triangle taken in one order, their resultant vector is represented in magnitude and directed by the third side of the triangle taken in opposite order.

If the angle between the vectors →A and →B is θ, M is the staring point (tail) of B (or head of A) and N is the head of B, then

R = √(A² + B² + 2AB cosθ)

Vector Resultant Equation

If α be the angle made by resultant with vector →A, then

tanα = B sinθ / A + B cosθ

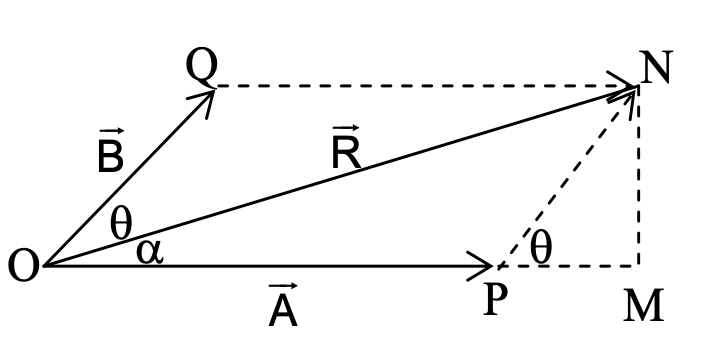

2. Parallelogram law:

If two vectors acting on a particle at the same time are represented in magnitude and direction by the two adjacent sides of a parallelogram drawn from a point, their resultant vector is represented in magnitude and direction by the diagonal of the parallelogram drawn from the same point.

If A and B be the vectors with same initial points making an angle θ with each other, to find the resultant of the vectors, complete the parallelogram as shown in the given figure. Draw line MN ⟂ OP and extend OP to M.

It is clear from the figure that

|R| = ON, |A| = OP, |B| = OQ

In right ΔPNM

PM = PN cosθ, MN = PN sinθ

As OQ = PN (adjacent sides of a parallelogram)

PM = OQ cosθ, MN = OQ sinθ

In right ΔONM

ON² = OM² + MN²

or ON² = (OP + PM)² + MN²

or R² = (A + B cosθ)² + (B sinθ)²

or R² = A² + B² + 2AB cosθ

or R = √(A² + B² + 2AB cosθ) …… (3)

To find the direction of vector R , let α be the angle made by vector R with vector A . Then in right ΔONM:

tan α = sinθ / (A + B cosθ) …… (4)

Note:

1) If both the vectors and B act in same direction, i.e θ = 0, then R = A + B.

2) If both the vectors A and B act in opposite direction, i.e. θ = 180° then R = A − B.

Properties of vector addition:

- Resultant of two vectors is always a vector.

- Vector addition is commutative i.e. vector A + B = B + A

- Vector addition is associative i.e. vector A + (B + C) = (A + B) + C

- If two vectors act in same direction their resultant will also be in the direction of vectors.

- If two vectors act in opposite directions their resultant will act in the direction of the vector having grater magnitude.

- Vectors having different nature cannot be added. For example displacement vector cannot be added to velocity vector but can be added to other displacement vector.

Note:

Both triangle law and parallelogram law of vector addition are equally applicable for subtraction of vectors.

Consider the condition shown in the above figure.

By parallelogram law of addition of vectors

|S| = √(A² + B² + 2AB cos(180° − θ) . ….. (5)

And tan α = B sin(180° − θ)/A + B cos(180° − θ .. (6)

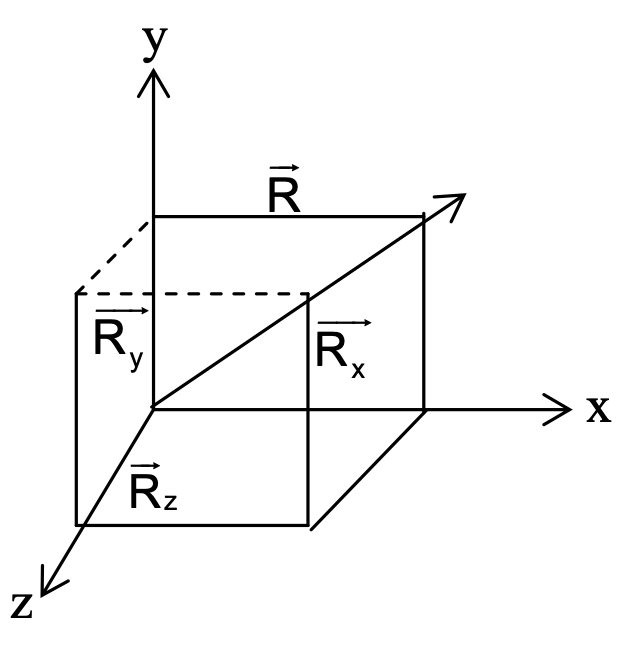

Rectangular Components of Vectors

Consider two vectors Rx and Ry. If R be the vector sum of these vectors, then

R = Rx + Ry

If î and ĵ be the unit vectors along x- and y-direction respectively then

R = Rx î + Ry ĵ

R = √(Rx2 + Ry2) .......(9)

tan θ = Ry / Rx ...........(10)

In three dimensions, R can be resolved into three rectangular components i.e. Rx, Ry and Rz then

R = Rx î + Ry ĵ + Rz k̂

Where k̂ is the unit vector along z-axis and

R = √(Rx2 + Ry2 + Rz2)

Note:

If A = Ax î + Ay ĵ + Az k̂ and B = Bx î + By ĵ + Bz k̂ then

A + B = (Ax + Bx) î + (Ay + By) ĵ + (Az + Bz) k̂

and vector A - B = (AX - BX) î + (AX - BY) + ĵ + (Az + Bz) k̂

Finding Resultant Using Rectangular Components

This is a very useful method to find the magnitude as well as the direction of resultant of two or more coplanar vectors. The problem must be solved stepwise taking care of the directions of vectors. The steps involved are as follows:

- Choice of axes: First step is to choose two mutually perpendicular directions as x and y-axes. The axes must be chosen in such a way that, the angles between all the vectors and axes must have optimal values.

- Find rectangular components of vectors: Once the axes are chosen, resolve all the vectors into their rectangular components. For example if →A and →B are two vectors and Ax, Ay, Bx, By be their respective x and y components then:

→A = Axî + Ayĵ and →B = Bxî + Byĵ - Add the respective components of all the vectors: Add the rectangular components of all the vectors. The results obtained are the rectangular components of the resultant, writing it in component form the resultant vector is obtained.

- Find magnitude and direction of the resultant vector: If →R = Rxî + Ryĵ be the resultant vector then find magnitude of resultant vector by: |→R| = √(Rx2 + Ry2) and angle made by it with x-axis by θ = tan-1 (Ry/Rx)

Vector Multiplication — Dot (Scalar) Product

There are two methods for multiplication of two vectors.

1. Dot or scalar product:

The dot or scalar product of any two vectors A and B can be given by

A º B = |A| |B| cos θ, where θ is the angle between A and B.

cos θ = A º B / |A| |B|

Properties of scalar product

- As its name implies, scalar product of two vectors is always a scalar quantity.

- Scalar product is commutative i.e. Aº B = B º A

- Scalar product obeys distributive law i.e. A º ( B + C ) = Aº B + Aº C

If A and B are two vectors given by

A = ax î + ay ĵ + az k̂, and B = bx î + by ĵ + bz k̂ then,

A ∘ B = (ax î + ay ĵ + az k̂) ∘ (bx î + by ĵ + bz k̂) = axbx î ∘ î + axby î ∘ ĵ + axbz î ∘ k̂ + aybx ĵ ∘ î + ayby ĵ ∘ ĵ + aybz ĵ ∘ k̂ + azbx k̂ ∘ î + azby k̂ ∘ ĵ + azbz k̂ ∘ k̂

Now,

î ∘ î = |î| |î| cos θ = 1 × 1 × cos 0° = 1 = î ∘ ĵ = k̂ ∘ k̂

and

î ∘ ĵ = |î| |ĵ| cos 90° = 0 = î ∘ k̂ = ĵ ∘ k̂ = k̂ ∘ î = î ∘ ĵ = k̂ ∘ ĵ

Therefore, A ∘ B = axbx + ayby + azbz ………… (13)

4. Component of vector A along vector B is given by A ∘ B / B

2. Cross or vector product:

As its name implies, cross product of two vectors A and B is always a vector whose magnitude is given by

|A × B| = |A||B| sin θ n ...(16)

where θ is angle between A and B.

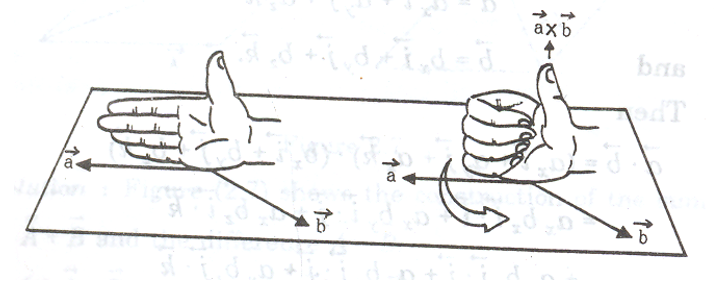

Direction of cross product of two vectors can be found by following two methods.

i) Right handed screw rule or right hand thumb rule: According to this rule, if the fingers of right hand be curled in the direction in which vector A must be turned through the smaller included angle θ to coincide with the direction of vector B, the thumb points in the direction of A×B or if a right handed screw is to rotated in a direction mentioned above, the direction of motion of the screw gives the direction of A×B.

Properties of cross or vector product of two vectors

-

Vector product is not commutative i.e. A × B ≠ B × A.

This is because if the direction of rotation is reversed, the direction of motion of screw will also change, hence A × B = −(B × A) (i.e. B × A is in a direction opposite to A × B).

- Vector product obeys distributive law i.e. A × (B + C) = A × B + A × C.

- Vector product of two vectors is always perpendicular to the plane containing the vectors.

- Vector product of two parallel vectors is always zero.

If A ∥ B, then θ = 0°

and |A × B| = |A| |B| sin 0° = 0

If A and B are any two vectors given by:

A = axi + ayj + azk

and

B = bxi + byj + bzk

Then

A × B = (axi + ayj + azk) × (bxi + byj + bzk)

= axbx(i×i) + axby(i×j) + axbz(i×k) + aybx(j×i) + ayby(j×j) + aybz(j×k) + azbx(k×i) + azby(k×j) + azbz(k×k)

It can be shown that

i×i = j×j = k×k = 0,

i×j = k, j×k = i, k×i = j

j×i = −k, k×j = −i, i×k = −j

Therefore,

A × B = (aybz − azby)i + (azbx − axbz)j + (axby − aybx)k

or

| i | j | k |

| ax | ay | az |

| bx | by | bz |

Applications of cross or vector product of two vectors:

- If vector a and b represent adjacent sides of a parallelogram, then |a × b| gives the area of the parallelogram.

- If d₁ and d₂ are two vectors representing the diagonals of a parallelogram, then the area of the parallelogram is given by ½ |d₁ × d₂|.