Laws of Chemical Combination

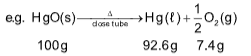

(i) Law of conservation of mass: In all physical and chemical changes, the total mass of the reactants is equal to that of the products. In other words, matter can neither be created nor be destroyed.

(ii) Law of constant composition or definite proportion: A chemical compound is always found to be made up of the same elements combined together in the same fixed proportion by weight.

For example, pure water obtained from whatever source or any country will always be made up of only hydrogen and oxygen elements combined together in the same fixed ratio of 1 : 8 by weight.

(iii) Law of multiple proportions: When two elements combine to form two or more chemical compounds then the weights of one of elements which combine with a fixed weight of the other bear a simple ratio to one another.

e.g. the weights of nitrogen and oxygen forming compound N2O, NO, N2O3, N2O4, N2O5, if we fix the weight of nitrogen as 14 then weight of oxygen bears a simple ratio 1 : 2 : 3 : 4 : 5 to one another.

(iv) Law of reciprocal proportions: The ratio of the weights of two elements A and B which combine separately with a fixed weight of the third element C is either the same or some simple multiple of the ratio of the weights in which A and B combine directly with each other. For example, CO2, SO2 and CS2, H2S, H2O and SO2.

(v) Gay Lussac’s law of gaseous volumes: When gases react together they always do so in volumes which bears a simple ratio to one another and to the volumes of the products, if these are also gases, provided all measurements of volumes are done under similar conditions of temperature and pressure. For example

N2 + 3H2 → 2NH3

1vol. 3vol. 2vol.

AVOGADRO’S HYPOTHESIS

Equal volumes of all gases under similar conditions of temperature and pressure contains equal number of molecules.

Applications of Avogadro’s law

(i) In the calculation of atomicity of elementary gases.

(ii) To find the relationship between molecular weight and vapour density of a gas.

Molecular weight = 2 x Vapour density

(iii) To find the relationship between weight and volume of a gas.

Molecular weight = Weight of 22.4 L of the gas at STP

MASS CONCEPTS

(i) Atomic Mass: The atomic mass of an element is a number which indicates how many times an atom of natural isotopic composition of an element is heavier as compared with 1/12 of mass of a atom of carbon-12.

(ii) Gram atomic mass: The atomic mass of an element expressed in grams is called Gram atomic mass e.g.,

Atomic mass of oxygen = 16 a.m.u.

Gram atomic mass of oxygen = 16 a.m.u

Note: (1 a.m.u. = 1.6 x 10-24 g)

(iii) Molecular mass: The molecular mass of a substance (element or compound) is the number of times, the molecule of substance is heavier than .png) of the mass of an atom of Carbon–12 isotope.

of the mass of an atom of Carbon–12 isotope.

(iv) Gram molecular mass: The molecular mass of a substance expressed in grams is called its Gram molecular mass.

1 gram molecule of H2SO4 = 98.0 g

(v) Atomic Mass Unit: The quantity 1/12th mass of and atom of carbon-12 is known as atomic mass unit.

1 amu = 0.012kg/6.023 x 1023 /12 = 1.66 X 10-27 kg

A mole is defined as number of atoms in 12g of carbo-12, which is experimentally found to be 6.023 x 1023.

Ex.: In naturally occurring neon, isotopes and their relative abundance are as follows:

Isotope Fractional Abundance

2oNe 0.9051

21Ne 0.0027

22Ne 0.0922

Average atomic mass of Ne is

(A)20.179

(B) 21.179

(C)22.179

(D) 20

Solution: (A)

Average atomic mass of Ne = 20 x 0.9051 + 21 x 0.0027 + 22 x 0.0922 = 20.179

Aliter

From the fraction abundance of various isotopes, clearly shows that the average atomic mass should be near to 20 (20Ne). Hence, (A) is correct

MOLE CONCEPT

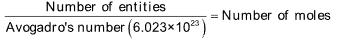

For counting of articles, units like dozen or score is commonly used. Similarly in chemistry ‘mole’ is the counting unit for chemical entities.

The amount of substance containing Avogadro’s number (6.023 x 1023) atom, molecule, ions, electrons and protons, i.e.

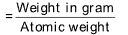

(i) Number of moles of molecule = Weight in gram / molecular weight

(ii) Number of moles of atoms = Weight in gram / atomic weight

(iii) Number of moles of gases = Volume at NTP / Standard molar volume (22.4 L)

(iv) Number of milli moles = molarity x volume in ml.

(v) For a compound PxQy

x moles of Q = y moles of P

(vi) Number of entities / Avogadro's number (6.023 x 1023) = Number of moles

Ex.: The number of atoms present in 11.2 L of SO2 at STP is

(A) 2.5 NA

(B) 2 NA

(C) NA /2

(D) 3/2 NA

Solution: (D).

Moles of SO2 = 11.2/22.4 = 1/2

Number of atoms = 3 x 1/2 x NA = 3/2 NA

Ex.: The volume (in L) of CO2 liberated at STP when 10 g of 90% pure lime stone is heated completely is

(A) 20.16

(B) 2.016

(C) 2.24

(D) 22.4

Solution: (B).

CaCo3 ⟶ CaO + CO2

Moles of CaCO3 = 10/100 x 90/100 = 0.09

Moles of CO2 = 0.09 = volume at STP/22.4

Volume at STP = 2.016 L

Ex.: 44.8 litre of CO2 at STP is obtained by heating x gm of pure CaCO3. x is

(A) 100 g

(B) 200 g

(C) 50 g

(D) 44.8 g

Solution: (B).

CaCO3 CO2 + CaO

CO2 + CaO

1 mol of CO2 is obtained from 1 mole of CaCO3

22.4 litre of gas at STP = 1 mol of gas

44.8 litre of gas at STP = 2 mol of gas

Hence,

2 mole of CO2 is obtained from 2 mole of CaCO3

i.e., 2 x 100 = 200 gm of CaCO3

DETERMINATION OF MOLECULAR FORMULAE

The percentage composition of a compound leads directly to its empirical formula. An empirical formula or simplest formula for a compound is the formula of a substance written with the smallest integer subscripts. The molecular formua of a compound is a multiple of its empirical formula.

(a) Law of isomorphism: Isomorphism substances form crystal which have same structure. Thus both the cation and anion of isomorphous substance have the same valency.

(b) Chemical formulae of a compound can be found out by the following steps:

(i) The percentage composition of compound is determined.

(ii) Then the percentage of each element is divided by the atomic mass and then a molar ratio of each element is obtained.

(iii) This molar ratio is divided by a minimum value to get the simplest ratio and an empirical formula is obtained.

(iv) Finally by comparing the molecular mass or vapour density of this empirical formulae to that of actual molecule its molecular formulae is obtained.

Ex.: An organic compound contains 49.3% carbon, 6.84% hydrogen and its vapour density is 73. Molecular formula of the compound is

(A) C3H8O2

(B) C3H10O2

(C) C6H9O

(D) C6H10O4

Solution: (D)

Step (i)

C = 49.3%, H = 6.84%

O = 43.86%

Step (ii)

C : H : O

or C : H : O = 4.11 : 6.84 : 2.74

Step (iii)

Dividing through out by 2.74

C : H : O = 1.5 : 2.54 : 1

or C : H : O = 3 : 5 : 2

Empirical formulae = C3H5O2

Empirical formula mass = 73

Molecular mass of compound = 73 x 2 = 146

Molecular formula = 146/73 x [C3H5O2] = C6H10O4

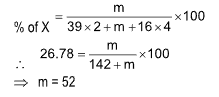

Ex.: A compound K2XO4 is isomorphous to potassium sulphate (K2SO4) and is found to contain 26.78% ‘X’. Calculate the mass of ‘X’?

(A) 22

(B) 26

(C) 52

(D) 44

Solution: (C).

Let the mass of ‘X’ can be m.

BALNCING REDOX REACTIONS

Quite often one has to write a balanced chemical equation while dealing with the problem on stoichiometry. After writing reactant and products, the balancing can be carried out by hit and trial method. However, systematic methods are available for balancing redox reactions. Before describing these methods, the rules governing the computation of oxidation state of an element are described in the following.

Rules to Compute Oxidation Number

The oxidation number of an element is the number assigned to it by following the arbitrary rules given below:

(i) A free element (regardless of whether it exists in monatomic or polyatomic form, e.g. Hg, H2, P4 and S8) is assigned an oxidation number of zero.

(ii) A free monatomic ion is assigned an oxidation number equal to the charge it carries. For example, the oxidation number of Al3+, S2- and Cl- are +3, -2 and -1 respectively.

(iii) In their compounds, the alkali and alkaline earth metals are assigned oxidation numbers of +1 and +2 respectively.

(iv) The oxidation number of hydrogen in its compounds is generally +1 except the ionic hydrides such as LiH, LiAlH4 where its oxidation number is -1.

(v) The oxidation number of fluorine in all its compounds is -1. The oxidation number of all other halogens is -1 in all compound except those with oxygen (e.g.CIO-4) and halogens having a lower atomic number (e.g. ICI-3 ). The oxidation number of the latter is determined via oxygen and halogen of lower atomic number.

(vi) The oxidation numbers of both oxygen and sulphur in their normal oxides (e.g. Na2O) and sulphides (e.g. CS2) is -2. The exception are the peroxides (e.g. H2O2 and Na2O2), superoxides (e.g. KO2) and the compound OF2. Their oxidation numbers are determined by the rules 3, 4 and 5.

(vii) The algebraic sum of oxidation numbers of atoms in a chemical species (compound or ion) is equal to the net charge on the species.

A few examples of the computation of oxidation number of atoms N in various compounds are given as follows.

If x is the oxidation number of N, we have

NH3 x + 3(+1) = 0 which gives x = -3

HN3 +1 + 3(x) = 0 which gives x = -1/3

N2H4 2x + 4(+1) = 0 which gives x = -2

NO2 x + 2(-2) = 0 which gives x = 4

N2O4 2x + 4(-2) = 0 which gives x = 4

NO-2 x + 2(-2) = -1 which gives x = 3

NH2OH x + 2(+1) + 1(-2) + 1 = 0 which gives x = -1

NO x + 1(-2) = 0 which gives x = 2

HNO3 +1 + x + 3(-2) = 0 which gives x = 5

H2O 2x + 1(-2) = 0 which gives x = 1

HCN +1 + 4 + x = 0 which gives x = -5

Balancing Redox Reactions Via Oxidation Numbers

The steps involved in this method are as follows:

1. Identify the elements in the unbalanced equation whose oxidation number are changed.

2. Balance the number of atoms of each element whose oxidation number is changed.

3. Find out the total change in oxidation number for each of oxidant and reductant and make them equal by multiplying by small coefficients.

4. Balance the remainder of atoms by inspection and add, if necessary H+(acidic medium) or OH-(alkaline medium) or H2O (to balance oxygen) as the case may be.

Ex.: Cu + 8H+ + yNO-3 ⟶ zCu2+ + 4H2O + 2NO

The values of x, y and z are respectively

(A) 3, 2, 3,

(B) 2, 3, 3

(C) 3, 3, 3

(D) 4, 3, 1

Solution: (A).

.png)

Ion – electron method or Half reaction method

The various steps involved are –

(i) Write the skeletal equation and indicate the oxidation number (O. N.) of each element.

(ii) Identify the elements which has undergone change in oxidation state.

(iii) Divide the skeletal equation into two half reactions i.e. oxidation half reaction and reduction half reaction. In each half reaction balance the atom which undergo change in oxidation number.

(iv) Add electron to whichever side is necessary to make up the difference in oxidation number in each half reaction.

(v) Balance oxygen atoms by addition of proper number of H2O molecules to side deficient in ‘O’ atoms.

(vi) For ionic equations – It involves the balancing of H atoms in each half reaction. (after O is balanced in each half reaction).

(a) For acidic medium: Add proper number of H+ ions to the side falling short of H atoms.

(b) For basic medium: Add proper number of H2O molecules to the side falling short of H atoms and equal number of OH- ions to the other side.

(vii) Equalise the number of electrons lost and gained by multiplying the half reactions with suitable integer and add them to get the final equation.

Note: It may be remembered that in balanced equation the number of atoms and also the electrical charges must be equal on both sides.

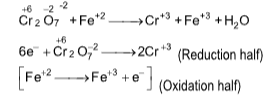

Ex.: wCr2O7-2 + xFe+2 ⟶ yCr+3 + zFe+3 + 7H2O (in acidic medium). Balance the reaction by ionic method and find the values of w, x, y and z respectively?

(A) 1, 7, 2, 6

(B) 1, 6, 2, 6

(C) 2, 6, 2, 6

(D) 3, 5, 3, 7

Solution: (B).

First balance ‘O’ adding equal number of H2O molecules and then ‘H’ atom by adding H+ to deficient side.

.png)

CONCEPT OF LIMITING REAGENT

When ever, the ratios of reactant molecules actually used in an experiment are different from those given by co–efficients of the balance equaiton, a surplus of one reagent is left over after the reaction is completed.

Thus the extent to which a reaction takes place, depends on the reactant that is present in limiting amount – the limiting reactant. The other reactant is said to be the excess reactant.

Consider the following chemical reaction

N2 = 3H2 ⟶ 2NH3

From the reaction, it is clear that 1 mol N2 reacts with 3 mol H2 to from 2 mol NH3.

If we take 1 mol N2 and 4 mol H2, even then 2 mol of NH3 are formed since 1 mol H2 is left unreacted. So in this case N2 is limiting reagent.

Now, if we take 2 mol N2 and 3 mol H2 even then 2 mol of NH3 are formed and 1 mol N2 is left unreacted. So in this case H2 is limiting reagnet.

Ex.: A sample of Ca3(PO4)2 contains 3.1 g phosphorus, the weight of Ca in the sample is

(A) 6 g

(B) 4 g

(C) 2 g

(D) 5 g

Solution: (A).

Mole of phosphorus = 3.1/31 = 1/10

Mole of Ca = 3/20

Weight of Ca = 3/20 x 40 = 6 gm

Ex. If 0.5 mol of BaCl2 is mixed with 0.2 mol of Na3PO4, the maximum number of moles of Ba3(PO4)2 that can be formed is

(A) 0.7

(B) 0.5

(C) 0.30

(D) 0.10

Solution: (D).

3BaCl2 + 2Na3PO4 ––⟶ Ba3(PO4)2 + 6NaCl

Here Na3PO4 is limiting

Hence moles of Ba3(PO4)2 = ½ of Na3PO4

= 1/2 x0.2 = 0.1 mole

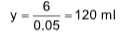

Volumetric Stoichiometry

The reactions in solutions are by far the most common. The first step to determine is to express the amount of substance present in a given volume of a solution.

Solution ––⟶ Solute + Solvent

Qualitative methods to express a solution are dilute, concentrated, saturated and super saturated.

Quantitative method involves the determination of concentration in different way as described below:

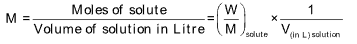

(i) Molarity: It is the number of moles of solute dissolved or present per litre of the solution. It is represented by the symbol M.

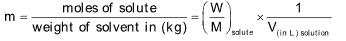

(ii) Molality: Number of moles of solute present or dissolve in 1000 g or 1 kg of solvent. It is represented by the symbol m.

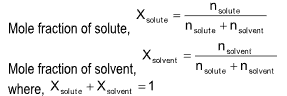

(iii) Mole fraction: It is the relative ratio of moles of solute and solution or solvent and solution.

Note: Molarity is temperature dependent while mole fraction and molality is temperature independent.

(iv) Strength: The strength of a solution is defined as the amount of the solute in grams present per litre of the solution (i.e. g/L).

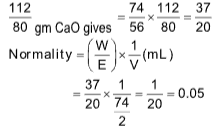

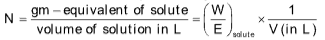

(v) Normality: The normality of a solution is defined as the number of gram equivalents of the solute present per litre of the solution, it is represented by N.

E = Equivalent weight

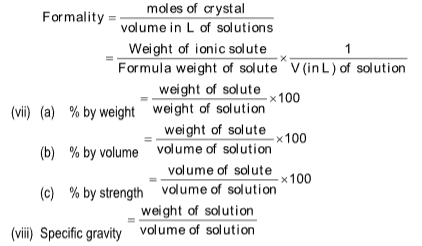

(vi) Formality: Formality is similar to Molarity. It is especially used for ionic crystals like Na+Cl–.

CALCULATION OF EQUIVALENT WEIGHT

Equivalent weight of an element can be calculated using the composition of the compound of the given element with any other element whose equivalent weight is known by the knowledge of the law of equivalence.

This law states that one equivalent of an element combines with one equivalent of the other.

Hence, the equivalent weight of an element is the weight of its mole combining with one equivalent of another element.

In general, equivalent weight = Molecular mass or atomic mass / n-factor

We can easily calculate equivalent weight if we know proper idea about n–factor. n–factor varies for element, salt, acid, base and redox as well as disproportionation reaction.

(i) Equivalent weight of element = Atomic weight / Valency of elements

(ii) Equivalent weight of acid = Molecular weight of acid/basicity of the acid (moles of H+ ion furnished in solution)

| Acid | Basicity (maximum) |

|---|---|

| HCl, HNO3, H3BO3 | 1 |

| H2SO4, H3PO3, H2C2O4·2H2O | 2 |

| H3PO4 | 3 |

| H4P2O7 | 4 |

(iii) Equivalent weight of base = molecular weight of base / addity of the base (moles of OH- ion furnished in solution)

| Base | Acidity (maximum) |

|---|---|

| NaOH, KOH | 1 |

| Ca(OH)2, Ba(OH)2 | 2 |

| AI(OH)3 | 3 |

(iv) E(salt) = Molecular weight of salt/Moles of metal atoms x valency of metal (total number of cations or anions)

Note: In case of hydrated salt mass of water is included but not the number of H+ ion.

(v) Equivalent weight of oxidizing and reducing agent = Molecular mass / Number of el3ctrons lost or gained by one mole reagnet or change in oxidation number per mole of the oxidising or reducing agent

(vi) Equivalent weight of an ion = Formula weight/charge on ion

Law of Equivalence

For a chemical reaction:

aA + bB ⟶ cC + dD

Or Equivalent of A = Equivalent of B = Equivalent of C = Equivalent of D

or wt. of A/EA = = wt.of B/EB = wt. of C / EC = wt. of D/ED

or NA = Wt. of A/MA = NB = Wt. of B / MB = NC = Wt. of C/MC = ND = Wt. of D/MD

where ni and Mi is n factor, molecular mass of ith species.

If the reaction is carried out in solution, then

NAVA = NBVB = NCVC = NDVD

or nAMAVA = nBMBVB = nCMCVC = nDMDVD

Normality equation

N1V1 = N2V2

Gram equivalent of acid = Gram equivalent of base (if volume in L)

Milliequivalents

Milliequivalents = Normality x volume(in ml)

For a given solution, number of equivalents per litre is same as the number of milliequivalents per ml. Moles, millimoles, equivalent, milli equivalent of solute does not change on dilution.

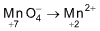

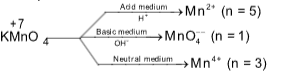

Example 12 : The equivalent weight of potassium permanganate (KMnO4) in acidic

medium is

(A)158 (B) 79

(C)31.6 (D) 316

Solution: (C).

2KMnO4 + 3H2SO4 ⟶ K2SO4 + 2MnSO4 + 3H2O + 5O

The net reaction is

Change in oxidation number = 7 - 2

= 5

Equivalent weight of KMnO4 = Molecular weight of KMnO4/Change in oxidation number = 158/5 = 31.6

Ex.: The equivalent weight of ferric oxalate in the reaction with KMnO4/H+ is

(A)M/6

(B) M/3

(C) M

(D) M/2

where, M = molecular weight of ferric oxalate.

Solution: (A).

n–factor for Fe2(C2O4)3 = 6x1 = 6

Equivalent weight = M/6

Ex.: 1.5 litre of a solution of normality N and 2.5 litres of 2M HCl are mixed

together. The resultant solution had a normality 5. The value of N is

(A) 6

(B) 10

(C) 8

(D) 4

Solution: (B).

Eq. of 1.5 litre solution + Eq. of 2.5 litre solution = Eq. of resultant of solution.

= 1.5 x N + 2.5 x 2 = 4 x 5

N = 20 - 5/1.5 = 15/1.5 = 10

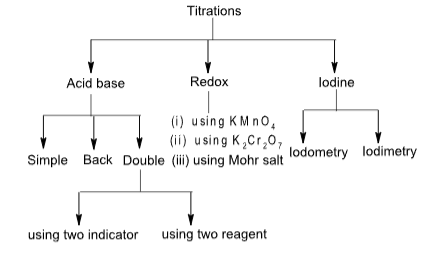

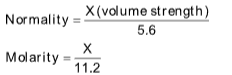

TITRATIONS

In volumetric analysis, the process of determination of strength of an unknown solution by another solution of known strength under volumetric conditions is known as titration. Titrations are of various types–The fundamental basis of all titration is the law of equivalence which states that at the end point, the milliequivalent of known solution is equal to milliequivalent of given unknown solution which is observed by using an indicator.

Simple titration

In a simple titration, a solution of substance A of unknown concentration is made to react with a solution of reagent B whose concentration is known, so that the concentration of A may be calculated.

N1V1 = N2V2

(A) (B)

N2 = (N1V1/V2)

Back titration

Let us assume that we have a solid C which is impure and we want to calculate the percentage purity. We are given two reagents A and B, where the concentration of A is unknown while that of B is known (N1).

Note: (i) A, B and C should be such that A reacts with B, A reacts with C and the product of A and C cannot react with B.

(ii) Gram equivalent of A should be either greater than or equal to gram equivalents of C.

meq. of C = (meq. of A – meq. of B)

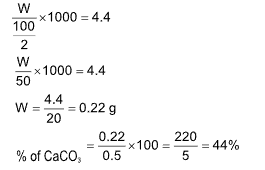

Ex.: 0.5 g of impure CaCO3 was treated with 50 ml of M/10 HCl. The excess of HCl was neutralized by 6 ml of M/10 NaOH solution. The percentage purity of CaCO3 is

(A) 84%

(B) 44%

(C) 21%

(D) 46%

Solution: (B).

meq. of excess of HCl = meq. of NaOH = 0.6

meq. of used HCl for CaCO3 = 5 – 0.6 = 4.4

meq. of CaCO3 = meq. of used HCl

Double titration

This is done by

(i) Using two indicators:

| Indicator | pH range | Colour | |

|---|---|---|---|

| In acid | In base | ||

| HPh (Phenolphthalein) | (8–10) | Colourless | Pink |

| MeOH (Methyl orange) | (3–4) | Orange | Yellow |

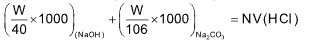

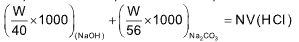

When the solution containing NaOH and Na2CO3 is titrated using phenolphthalein indicator, following reaction takes place at the end point

NaOH + HCl ──⟶ NaCl + H2O

Na2CO3 + HCl ──⟶ NaHCO3 + NaCl

meq. of NaOH + meq. of Na2CO3 = meq. of HCl

… (i)

… (i)

When MeOH is used Na2CO3 convert into NaCl + CO2 + H2O

meq. of NaOH + meq. of Na2CO3 = meq. of HCl

… (ii)

… (ii)

(ii) Using two reagents:

Mixture of (H2C2O4 + H2SO4)  (complete reaction)

(complete reaction)

Mixture of (H2C2O4 + H2SO4)  (complete neutralization)

(complete neutralization)

For step (i), H2SO4 + H+ + KMnO4 ⟶ Mn2+ + CO2 + H2O

Meq. of H2SO4 = Mqe. of KMnO4

(n=2) (n=5)

For step (ii), meq. of H2SO4 = meq. of NaOH

Ex.: 40 ml of 0.05 M solution of sodium sesquicarbonate

(Na2CO3.NaHCO3.2H2O) is titrated against 0.05 M HCl. X ml of HCl is

used when phenolphthalein is the indicator and y ml of HCl is used

when methyl orange is the indicator in two separate titrations. Hence

(y–x) is

(A) 80 ml (B) 30 ml

(C) 120 ml (D) 180 ml

Solution: (A). Millimole of mixture = Millimole of Na2CO3

=40 x 0.05 = 2 millimole = millimole of NaHCO3

Millimole of Na2CO3 = Millimole of HCl

2 = 0.05 x

x = 40 ml

meq. of Na2CO3 + meq. of NaHCO3 = meq. of HCl

2 x 2 + 1 x2 = 0.5g

x = 120 – 40 = 80 ml

Redox titration

It is a common reaction used in redox titration.

(i) 2KMnO4 + 3H2SO4 ──⟶K2SO4 + 2MnSO4 + 3H2O +5O

(n = 5)

(ii) K2Ce2O7 + 4H2SO4 ──⟶ K2SO4 + Cr(SO4)3 + 4H2O + 3O

(n = 6)

(iii) 2[Fe(SO4).(NH4)2SO4.6H2O]+ H2SO4 + O ⟶Fe2(SO4)3 + 2(MnO)2SO4 + 13H2O

Valency of KMnO4 in different medium:

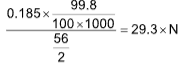

Ex.: 0.185 g of an iron wire containing 99.8% iron is dissolved in an acid

to form ferrous ions. The solution requires 29.3 ml of K2Cr2O7

solution for complete reaction. The normality of the K2Cr2O7 solution

is

(A) 0.02 (B) 0.025

(C) 0.01 (D) 0.05

Solution: (C).

Fe2+ + K2 O7 + H+ ──⟶Cr3+ + Fe3+

O7 + H+ ──⟶Cr3+ + Fe3+

n=1 n=6

meq. of Fe2+ = meq. of K2Cr2O7

N = 0.01 (approx)

Iodine titration

Titrations involving compounds of iodine are known as Iodometric titrations. Iodine molecules, I2 gives blue colour with starch. Thus, the completion of reaction can be detected when blue colours disappears at the end of the reaction.

(i) Iodometric: When an iodine containing sample is treated with oxidising reagent (KMnO4, K2Cr2O7, CuSO4, H2O2 and O3). Iodine so liberated is then treated with hypo solution, meq. of which is known to us.

i.e. 2KI + H2O2 ──⟶2KOH + I2

I2 + 2Na2S2O3 ──⟶2NaI + Na2S4O6

meq. of hypo = meq. of I2 = meq. of H2O2

(ii) Iodimetric: In this titration, I2 is directly treated with a reducing agent.

I2 + 2Na2SO3 ──⟶Na2SO4 + NaI

I2 + Na3AsO3 ──⟶Na3AsO4 + NaI

I2 + 2Na2S2O3 ──⟶ Na2S4O6 + 2NaI

meq. of I2 = meq. of hypo or reducing agent

VOLUME STRENGTH OF H2O2

X volume strength of H2O2 means X litre of O2 is liberated by 1 L of H2O2 on decomposition at STP.

POINTS TO PONDER

1. Stoichiometry is that branch of chemistry which deals with quantitative interpretation of chemical reaction.

2. Law of conservation of mass states that, matter can neither be created nor be destroyed.

3. For ideal gases molecular weight of the gas is twice its molecular weight.

4. Weight of 1 mol of a substance is equal to its molecular weight.

5. 1 mole of an ideal gas occupy a volume of 22.4 litre at standard temperature and pressure (STP).

6. Standard temperature and pressure refers to 0C and 1 atm pressure respectively.

7. Limiting reagent is completely consumed during chemical reaction.

8. The law of equivalence states that are equivalent of an element or compound combines with one equivalent of the other.

9. Equivalent weight calculated by dividing molecular mass or atomic mass with n-factor.

10. Titration is the process of determining strength of an unknown solution by another solution of known strength.

SOLVED EXAMPLES

1. The oxidation number of Cr is +6 in

(A) FeCr2O4

(B) Fe2(CrO4)2

(C) Cr2(SO4)3

(D) [Cr(OH)4]–

Sol. (B).

2(+2) + 2[x + 4(-2)] = 0

Here x is oxidation number of Cr

+4 + 2x – 16 = 0

2x = +12

x = +6

2. Oxidation number of chromium pentoxide (CrO5)

(A) +5

(B) +10

(C) +8

(D) +6

Sol. (D).

Butterfly Structure

x + 1 (–2) + 4 (–1) = 0

x = +6

3. Which of the following process is used to remove temporary as well as permanent hardness in water?

(A) Boiling the water with a calculated quantity of Na2CO3 solution and then with HCl

(B) Treating the water with a Ca(OH)2 solution and then with HCl

(C) Boiling the water with carbon

(D) Boiling the water with anhydrous CaCl2

Sol. (A).

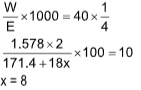

4. 1.578 g Ba(OH)2.xH2O neutralizes 40 ml of an N/4 HNO3 solution. The value of x is

(Ba = 137.4)

(A) 3

(B) 6

(C) 4

(D) 8

Sol. (D). meq. of Ba(OH)2.xH2O = meq. of HNO3

5. Find the ratio of number of molecules contained in 1 gm of NH3 and 1 gm N2

(A) 20: 17

(B) 28: 17

(C) 17: 28

(D) 14: 17

Sol. (B).

Ratio of moles

6. What is the relation between volume strength and normality of H2O2 solution?

(A) Volume strength = 5.6 ´ normality

(B) normality = 5.2 ´ volume strength

(C) Volume strength = 1.78 ´ normality (D) normality = 2.8 ´ volumes strength

Sol. (A).

Normality = Volume strength/5.6

7. The weight of Na2CO3 required to completely neutralize 45.6 ml of 0.235 N H2SO4 acid will be

(A) 0.47 g

(B) 0.57 g

(C) 0.67 g

(D) 0.77 g

Sol. (B).

meq. of Na2CO3 = meq. of H2SO4

W/53 x 1000 = 45.6 x 0.235

W = 45.6 x 0.235 x 53 / 1000 = 0.57 gm (approx)

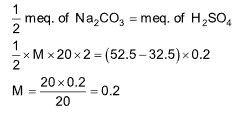

8. 20 ml solution containing NaOH and Na2CO3 required 32.5 ml 0.2 N H2SO4 for the end point using phenolphthalein as indicator. In another titration 20 ml solution of the mixture required 52.5 ml 0.2 N H2SO4 for the endpoint using MeOH as indicator. Hence, molarity of solution in respect of Na2CO3 was

(A) 01.

(B) 0.2

(C) 0.05

(D) None of these

Sol. (B).

In first case using Phenolphthalein,

meq. of NaOH + meq. of Na2CO3 = meq. of H2SO4

n=1 …(1)

In second case using Methyl orange,

meq. of NaOH + meq. of Na2CO3 = meq. of H2SO4

n=2 …(2)

From (1) and (2) we get,

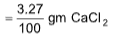

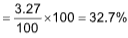

9. A 10.0 g samples of a mixture of calcium chloride and sodium chloride is treated with Na2CO3 to precipitate the calcium carbonate. This CaCO3 is heated to convert all the calcium to CaO and the final mass of CaO is 1.62 gms. The % by mass of CaCl2 in the original mixture is

(A) 15.2%

(B) 32.7%

(C) 21.8%

(D) 11.07%

Sol. (B).

CaCl2 + Na2CO3 ⟶CaCO3 + 2NaCl

113 100

CaCO3.png) CaO + CO2

CaO + CO2

100 56

56 gm CaO Formed by = 100 g CaCO3

1.62 gm will formed by  CaCO3

CaCO3

100 gm of CaCO3 is formed by = 113 g CaCl2

will be formed by

will be formed by .png) = 3.27 gm

= 3.27 gm

10.0 gm contains = 3.27 g CaCl2

1 gm contains

100 gm contains  of CaCl2

of CaCl2

10. 1g of Ca was burnt in excess of O2 and the oxide was dissolved in water to make up one litre solution. The normality of solution is

(A) 0.04

(B) 0.4

(C) 0.05

(D) 0.5

Sol. (C).

2Ca + O2 ⟶2CaO

80 112

CaO + H2O ⟶ Ca(OH)2

56 74

80 gm gives = 112 gm CaO

1.0 gm gives

56 gm CaO gives = 74 g Ca(OH)2