INTRODUCTION

A homogeneous mixture of two or more components in which the phase of at least one component belongs to the phase of solution, that component is known as solvent and others as solute. The size of solute particle differentiate solution [0.2 – 2.0 nm] from its contemporary colloids [2.0–1000 nm] and suspension in which particle diameter is greater than 1000 nm and they are unstable and particle settle down due to gravitational pull.

Types of solution

There are nine possible combinations of the three phases of solid, liquid and gas. Some important combinations are given below:

| Sr. No. | Combination | Example |

|---|---|---|

| (i) | Gas in gas | Air (O₂ + N₂ + Ar + CO₂) |

| (ii) | Gas in liquid | Cold drinks (carbonated water) |

| (iii) | Gas in solid | H₂ in palladium metal |

| (iv) | Liquid in liquid | Gasoline mixture, wine |

| (v) | Liquid in solid | Dental amalgam (mercury in silver), H₂O in CuSO₄ crystal |

| (vi) | Solid in liquid | Sugar syrup |

| (vii) | Solid in solid | Brass, 14–carat gold |

Essentials to Identify or Rank Solvent in a Solution:

-

Phase Rule:

The phase of the solution is the same as the phase of the solvent.-

Example: For gas or solid dissolved in a liquid, the solvent is liquid.

-

-

Major Component Rule (for liquid–liquid solutions):

In binary or ternary liquid solutions, the component with the largest proportion is considered the solvent. -

Special Rule for Aqueous Solutions:

If water is a component, it is generally called the solvent, even if it is in lesser proportion in some cases, due to its role as the universal solvent.-

Example: In ethyl alcohol + water solution, water is the solvent.

-

Concentration units and ways of expression

- Mass percentage: Mass% = (wt. of solute / wt. of solution) × 100

- Volume percentage: Vol% = (Vol. of solute / Vol. of solution) × 100

- Molality (m): m = moles of solute / weight of solvent (in kg)

- Molarity (M): M = moles of solute / litres of solution

- Normality (N): N = no. of gram equivalents of solute / litres of solution

- Mole fraction: Xsolute = n / (n + N) ; Xsolvent = N / (n + N)

Example-1 : A student finds that 31.26 ml of a 0.165 M solution of barium hydroxide, Ba(OH)2, solution is required to just neutralize 25.00 ml of a citric acid, H3C6H5O7, solution. What is the concentration of the H3C6H5O7 solution?

(A) 0.413 M

(B) 0.309 M

(C) 0.206 M

(D) 0.138 M

Solution. (D).

Citric acid is tricarboxylic acid, so ‘n’ factor is 3

Ba(OH)2 vs citric acid

2 × M1V1 = 3 × M2V2

M2 = (2/3) × (M1V1 / V2)

= (2/3) × (0.165 × 31.26 / 25)

= 0.138 M

Example 2: What is the density (in g ml–1) of a 3.60 M aqueous sulfuric acid solution that is 29.0% H2SO4 by mass?

(A) 1.22

(B) 1.45

(C) 1.64

(D) 1.88

Solution. (A).

Density = (3.6 × 98) / (10 × 29) = 1.22

Molarity = (10 × density × percentage) / Molecular weight

Vapour pressure of solution

The tendency of vaporisation is some what in lesser extent in solution than pure solvent because the solvent–solvent molecule attraction force is less than the solvent–solute attraction force so escaping tendency of solvent molecule in solution from liquid phase to vapour phase becoming less than pure solvent.

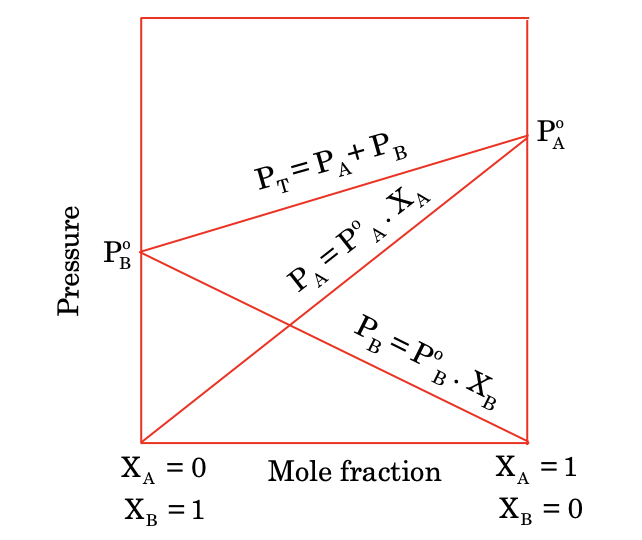

Raoults law for volatile solutes

The vapour pressure of any component at given temperature is the product of mole fraction of the component in solution with vapour pressure of the component in pure state.

For a binary mixture of two volatile components A and B with mole fraction XA and XB with pure component pressure PA0 and PB0 respectively.

According to Raoult's law:

PA = PA0 × XA

PB = PB0 × XB

where, PA and PB are vapour pressures of A and B above the solution they form.

So total pressure PT = PA + PB:

PT = PA0 × XA + PB0 × XB

The solutions which are ideal obey Raoult's law for any composition of A and B.

The vapour pressure of solution containing non-volatile solute is less than pure solvent vapour pressure, why?

Explanation: The attraction between solute and solvent molecules is greater than the attraction force among solvent–solvent molecules so the escaping tendency from liquid phase to gaseous phase becomes less due to increased attraction by molecule.

The relation between mole fraction of solvent and vapour pressure was first pointed out by Francis Marie Raoult's "Vapour pressure of solution is proportional to the mole fraction of solvent".

PA ∝ XA

PA = PA0 × XA[As for pure solvent XA = 1, PA = PA0]

where,

• PA = vapour pressure of solution,

• PA0 = vapour pressure of pure solution,

• XA = mole fraction of solvent

PA = PA0 [1 – XB]

where, XB is mole fraction of single non-volatile solute in solution.

PA0 – PA = PA0 XB

( PA0 – PA PA0 ) = XB

ΔP/PA0 = relative lowering of vapour pressure and is equal to mole fraction of non-volatile solute

All above relation is valid only for ideal solutions (that practically never exist but assumed that solution having concentration < 0.2 M are ideal).

So, ideal solutions are those which obey Raoult’s law for all composition.

Determination of Molar Masses from Lowering of Vapour Pressure

It is possible to calculate molar masses of non-volatile non-electrolytic solutes by measuring vapour pressures of their dilute solutions.

Suppose, a given mass, w gram, of a solute of molar mass m, dissolved in W gram of solvent of molar mass M, lowers the vapour pressure from \( P_1^0 \) to \( P_1 \).

Then, by Equation

\[ \frac{P_1^0 - P_1}{P_1^0} = \frac{n}{N+n} = \frac{w/m}{W/M + w/m} \]

Since in dilute solutions, n is very small as compared to N, Hence

\[ \frac{P_1^0 - P_1}{P_1^0} = \frac{n}{N} = \frac{w/m}{W/M} = \frac{w M}{W m} \]

or,

\[ m = \frac{wM}{W(P_1^0 - P_1)/P_1^0} \]

Example 3: The vapour pressure of pure benzene at 25°C is 639.7 mm Hg and the vapour pressure of a solution of solute in benzene at 25°C is 631.9 mm Hg. The molality of the solution is

- (A) 0.156

- (B) 0.108

- (C) 5.18

- (D) 0.815

Solution: (A).

Molality = (P0 - Ps/P0) × 1000 / M

Putting the known values, ‘M’ = 0.156 moles/kg

Example 4: If P0 & Ps be the vapour pressure of solvent and its solution respectively and N1 and N2 be the mole–fractions of solvent and solute respectively, then

- (A) Ps = P0 × N2

- (B) P0 = Ps = P × N2

- (C) Ps = P0 × N1

- (D) (P0 - Ps/Ps) = N1/(N1 + N2)

Solution: (C)

IDEAL SOLUTION

Ideal solution obeys Raoult’s law for binary mixture of component A and B present in mixture with mole fraction Xₐ and Xᵦ. If both components are volatile in nature then partial pressure of each component PA and PB should be less than Pₐ⁰ [Pure component vapour pressure of A] and Pᵦ⁰.

But,

PA = Pₐ⁰ × Xₐ

PB = Pᵦ⁰ × Xᵦ

So, PA + PB = Ptotal = Pₐ⁰Xₐ + Pᵦ⁰Xᵦ

If a graph is plotted between vapour pressure and composition for ideal solution PA, PB, Ptotal are represented by straight lines.

So, it can be stated in another way that ideal solution is that solution which obey Raoult’s law for any concentration.

This type of ideality is impossible in actual practice. This is why solutions with very dilute [< 0.2 M] assumed to behave ideally.

For ideal solution each component must have symmetry both in size and nature (molecular attraction with each other otherwise they do not behave ideally.

So for ideal solution,

ΔHmix = 0, ΔVmix = 0

Ptotal = P0AXA + P0BXB

Some examples of solution that is nearest to ideality.

(i) Benzene + Toluene

(ii) Hexane + Heptane

(iii) Ethyl bromide + Ethyl iodide

(iv) Chlorobenzene + Bromobenzene

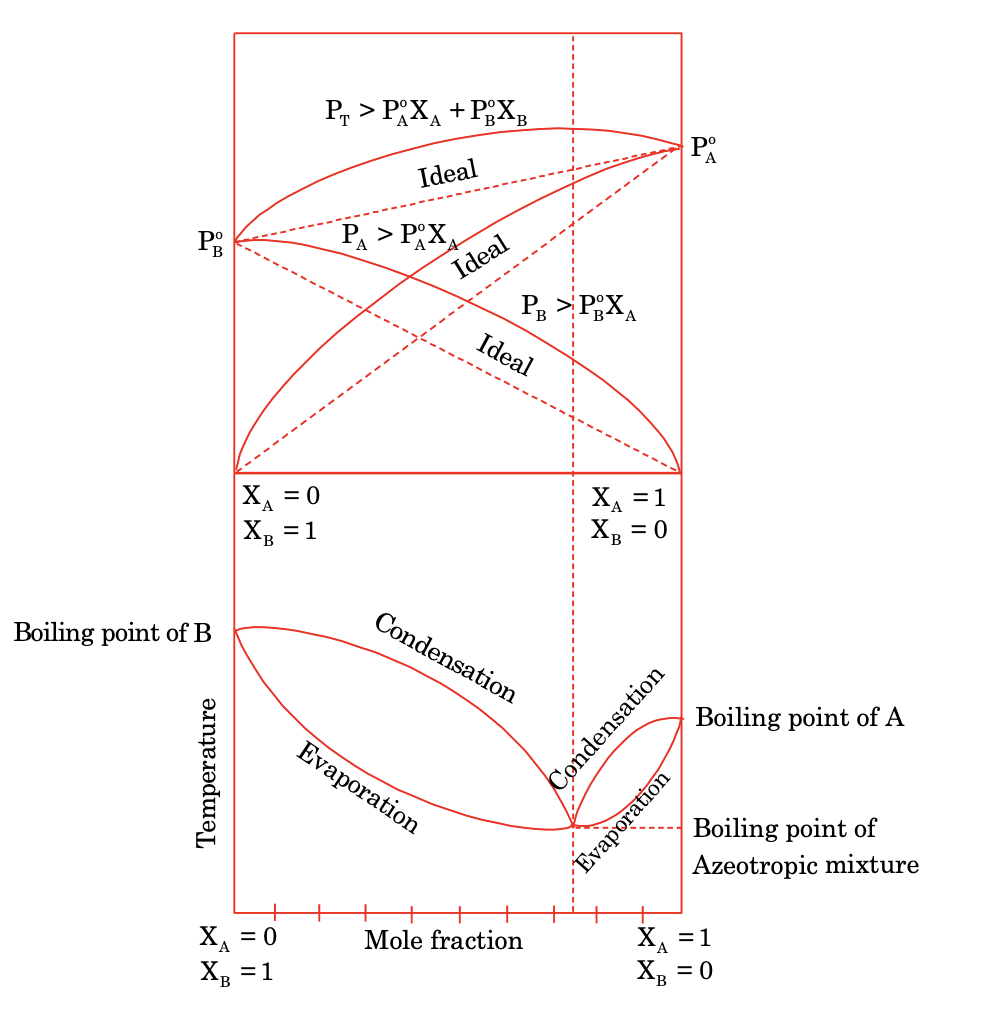

NON IDEAL SOLUTION

Due to dissymmetry in the size and nature of different components, they do not obey Raoult’s law. There are two type of non ideal solution of liquid components exists.

(a) Non ideal solution with positive deviation: They are characterised by

ΔHmix = +ve (endothermic)

ΔVmix = +ve (increase in volume)

Ptotal > PA + PB

Ptotal > P0AXA + P0BXB

PA > P0AXA; PB > P0BXB

This type of deviation occurs in components in which molar attraction is negligible with large size and shape difference.

They form minimum boiling azeotropic solution at a given composition.

Examples of non ideal solutions with positive deviation

(i) Acetone + Carbon disulphide

(ii) Acetone + Ethyl alcohol

(iii) Benzene + Acetone

(iv) Water + Methyl alcohol

(v) Ethyl alcohol + Water

(vi) Carbon tetrachloride + Chloroform

(vi) Carbon tetrachloride + Benzene

(vii) Carbon tetrachloride + Toluene

The boiling point of such composition mixture is lower than pure component boiling point of A and B respectively.

Azeotropic mixture can not be separated by simple distillation method because the composition of both vapour and liquid phase is same for both component and the boiling point remains constant till all the rest mixture evaporate so they can not be separated and they are also known as constant boiling mixture.

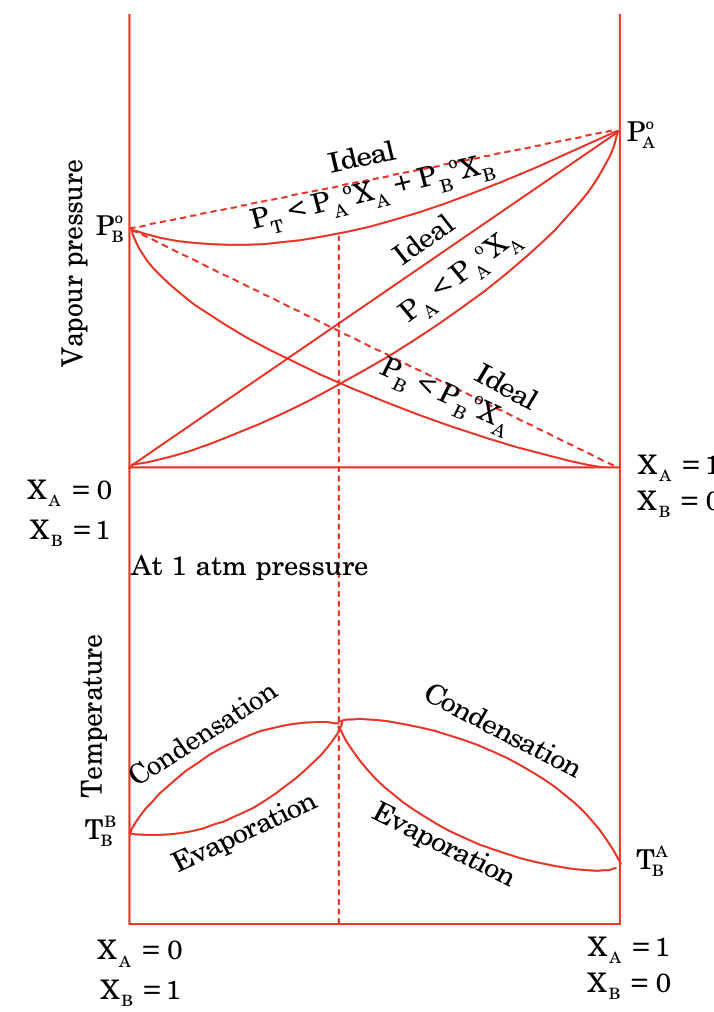

(b) Non–ideal solution with negative deviation

When the amount of molecular attraction between components A and B is valid and favoured by shape and size of them at proper composition. These are characterised by

- ΔHmix < 0

- ΔVmix < 0

- PA < PoAXA ; PB < PoBXB

- Ptotal < PoAXA + PoBXB

Such mixture form maximum boiling point azeotropic at definite composition.

Examples of non ideal solutions with negative deviation

- Chloroform + Benzene

- Chloroform + Acetone

- Chloroform + Diethyl ether

- Acetone + Aniline

- HCl + H2O

- HNO3 + H2O

- CH3COOH + Pyridine

Colligative Properties

The properties is depends upon the number of particles of solute in solution are called colligative properties. The following four colligative properties are:

(i) Relative Lowering of Vapour

The vapour pressure of solution containing non–volatile solute is less than pure solvent vapour pressure. This lowering of vapour pressure was formulated by Raoult’s law for

(a) Non volatile solute in solution

(b) For liquid component solution

The relation between mole fraction of solvent and vapour pressure is given by

⇒ (PAo - PA) / PAo = XB

⇒ ΔP / PAo = relative lowering of vapour pressure and is equal to mole fraction of non volatile solute

Example: One mole of non–volatile solute is dissolved in two moles of water. The vapour pressure of the solution relative to that of water is

(A) 2/3

(B) 1/3

(C) 1/2

(D) 3/2

Sol. (A).

PA / PAo = XA = 2 / (2+1) = 2 / 3

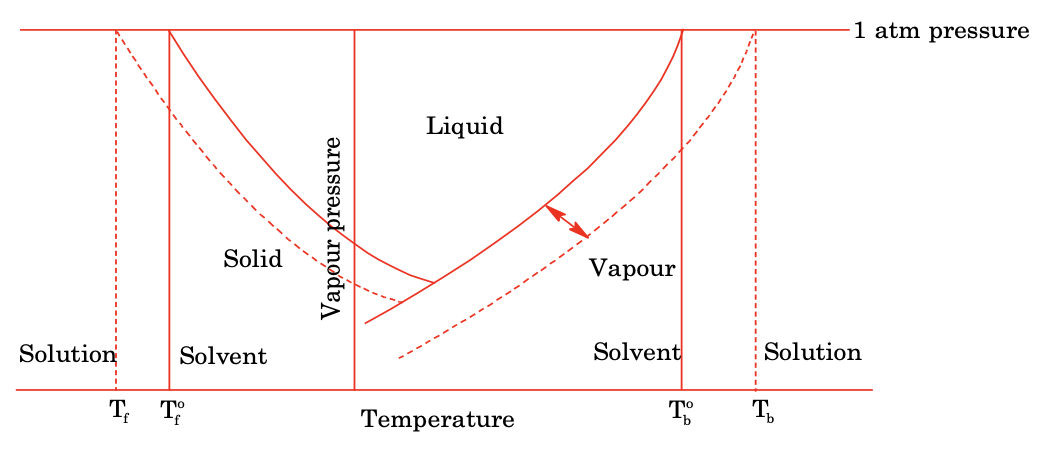

(ii) Depression in freezing point

The vapour pressure of a solution is always less than the pure solvent. Plotting the graph between vapour pressure and temperature for a phase diagram of solvent and solution. The curve obtained for solution lies below the curve of pure solvent and almost parallel.

For depression in freezing point

ΔTf = Tf° – Tf ∝ ΔP/P° (Relative lowering of vapour pressure)

⇒ ΔTf ∝ XB

∝ WB/MB × 1000 / WA/MA × 1000 [XB = WB/MB / ( WA/MA + WB/MB) (neglecting WB/MB in denominator)]

ΔTf ∝ (WB × 1000) / MB / WA/MA × MA/1000

ΔTf = MA · Kf / 1000 · m = Kf · m

where, Kf = molal depression constant

m = molality of solution

The unit for Kf = degree mol−1 kg

The Kf is the property of solvent.

(iii) Elevation in boiling point

As seen from graph plotted in figure.

ΔTb = Tb − Tb° ∝ Relative lowering of vapour pressure

⇒ ΔTb ∝ XB

∝ WB/WA × MA/(MA + MB) [WB/MB is neglected in denominator as it is small]

⇒ ΔTb ∝ WB/WA × 1000/MB × MA/1000

⇒ ΔTb = K · MA / 1000 · m = Kb · m

where, Kb = molal elevation constant having unit degree kg mol−1 and property of solvent only and m = molarity.

The value of Kf or Kb can be determined following the equation

Kf = 0.002 Tf2 / Lf ; Kb = 0.002 Tb2 / Lv

where, Lf and Lv are latent heat of freezing and vaporisation in cal/gm respectively and Tf = fusion temperature and Tb = boiling temperature at one atm pressure in Kelvin.

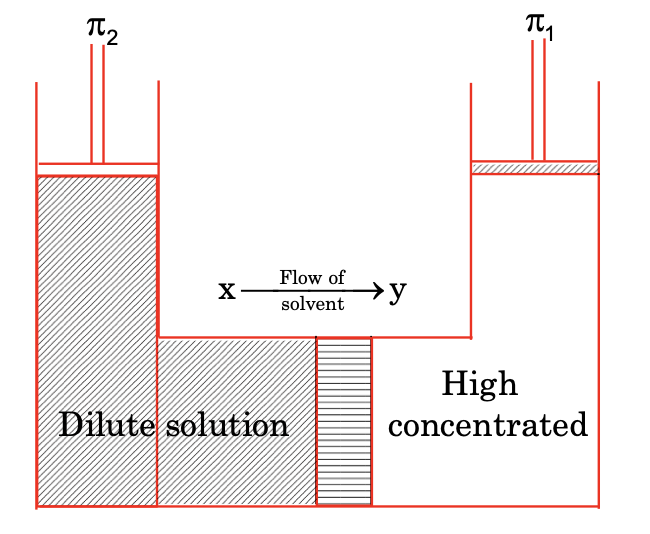

OSMOSIS

The flow of solvent from lower concentration solution towards high concentration separated by the semipermeable membrane (a membrane which only allows only liquid particles to pass through it) is known as osmosis.

Osmosis is also a colligative property of solution which depends on the concentration of solution and not on the nature of solute.

The phenomenona of osmosis play important part in all biological activity for the working of cell. For example: water rising up to leaf of long tall plant from soil, swelling of egg shell in fresh water shrinkage of egg in saline water etc. The preservation of pickle or fruit by keeping them in salt or sugar solution is also an application of osmosis. The water in bacterial cell comes out due to osmosis on high concentration salt and they perish.

(iv) Osmotic pressure

The pressure applied to stop the phenomenon of osmosis is known as osmotic pressure. It is indicated by π and has an analogous formula to ideal gas.

PV = nRT

P = (n/V) RT

↓ ↓

π = CRT

where,

π = osmotic pressure,

C = molarity (mol/litre),

R = gas constant,

T = temperature (kelvin)

The unit for π is taken as atmospheric pressure. R = 0.082 litre atm/K mol.

ABNORMAL COLLIGATIVE PROPERTIES

The colligative properties of solution depend upon the number of solute particles present in solution. When the substance undergoes dissociation the number of particles increases and hence an increase in colligative property. In another case, the particles when associates, the number of particles decreases and a decrease in the colligative properties.

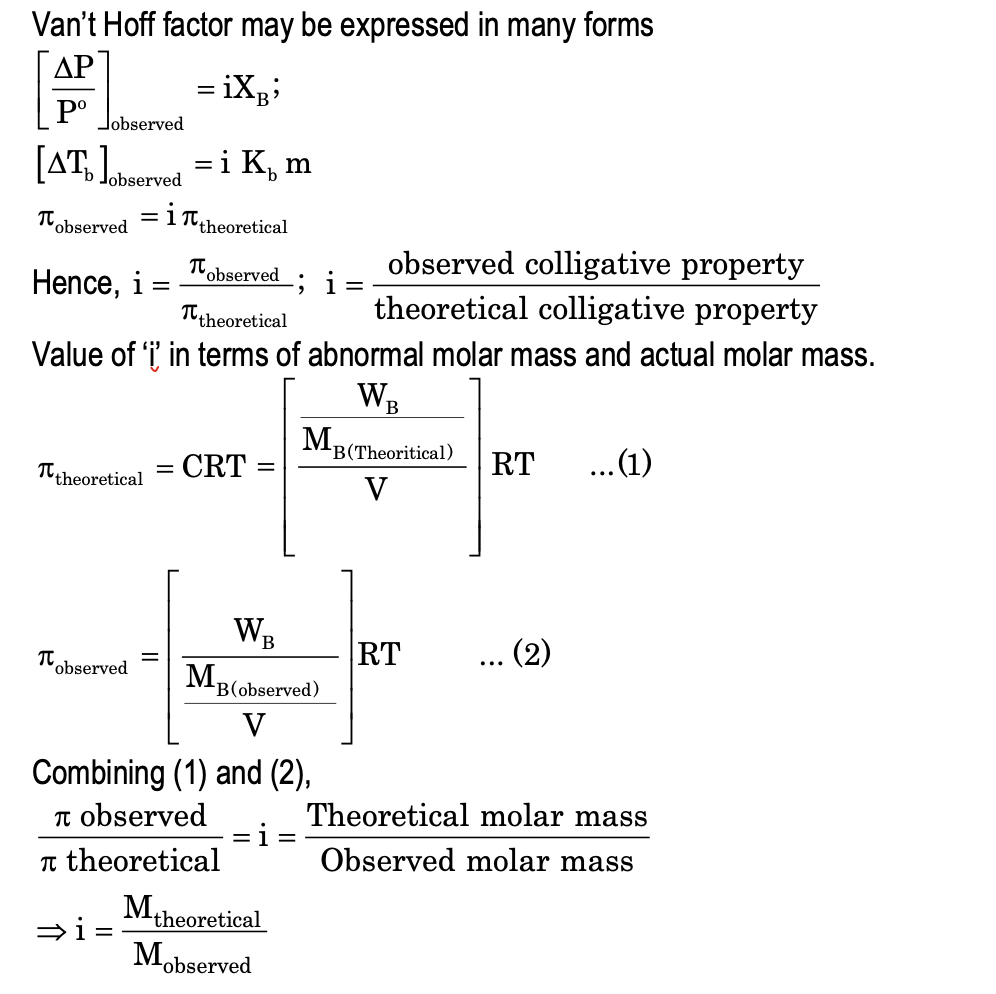

van’t Hoff Factor

Electrolytes dissociates or associates in aqueous solution and thus brings change in molality, molarity, mole fraction.

When some substance polymerises in solution, like acetic acid dimerises in benzene but dissociates in water give rise to abnormal concentration in contrast to as thought earlier.

So, there is change in colligative property and the ratio of observed colligative property with theoretical colligative property is known as Van’t Hoff factor ‘i’. The value of i > 1 for dissociation and i < 1 for association and extent of ‘i’ depends on the degree of dissociation or association.

In case of dissociation: For an electrolyte under dissociation and degree of dissociation α, we have

AxBy → xA+y + yB-x

| Initially | After dissociation | |

|---|---|---|

| AxBy | 1 | 1 - α |

| xA+y | 0 | xα |

| yB-x | 0 | yα |

Total number of moles of particle after dissociation = 1 - α + xα + yα

= 1 + α[x + y - 1]

Van’t Hoff factor,

i = observed number of mole / Theoretical value = 1 + α[x + y - 1] / 1

In case of association: Suppose n moles of any substance polymerises.

nA → An

| Initially | After association | |

|---|---|---|

| nA | 1 | 1 - α |

| An | 0 | α / n |

Total number of mole after association = 1 + α (1/n - 1)

Observed colligative property = 1 - α + α/n

1 - α [1 - 1/n] / 1 = (n - αn - 1)/n = (n(1 - α) - 1)/n

So, i for association is < 1.

Azeotropes

Azeotropic mixtures or constant boiling mixtures are such mixtures whose liquid phase compositions are similar to that of vapour phase composition and due to this nature, they can not be separated by simple distillation.

To separate each component successfully a third component named entrainer is mixed which form heteroazeotrope with one of the component and having different boiling point (lower and higher) than previous azeotropes boiling point and thus make it easy to separate.

For example:

Water (weight – 4.5%, boiling point – 100oC) and Ethyl alcohol (weight – 95.5%, boiling point – 78.5oC) form low boiling point azeotrope (78.15oC) if desired further separation to obtain pure ethyl alcohol, benzene is added (known as entrainer) to former azeotropic mixture and makes it hetero–azeotrope with alcohol having boiling point 67.8oC. It then boils quickly than the remaining mixture and maximum of alcohol is separated further with benzene.

Azeotropic mixture with positive deviation (minimum boiling)

| Components name | Composition by weight% of B | Boiling Point (K) | Azeotropic mixture | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | A | B | ||

| H₂O | C₂H₅OH | 95.37 | 373 | 351 | 351.15 |

| H₂O | C₃H₇OH | 71.69 | 373 | 370 | 350.72 |

| Acetone | CS₂ | 67 | 329.25 | 319.25 | 319.25 |

| CHCl₃ | C₂H₅OH | 68.6 | 334.2 | 323 | 332.3 |

Azeotropic mixture with negative deviation (maximum boiling)

| Components name | Composition by weight % of B | Boiling Point (K) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | A | B | Azeotropic mixture | |

| H₂O | HCl | 20.3 | 373.0 | 188 | 383 |

| H₂O | HI | 57.0 | 373.0 | 239 | 400 |

| H₂O | HNO₃ | 68.0 | 373.0 | 359 | 393.5 |

| H₂O | HClO₄ | 71.6 | 373.0 | 383 | 476 |

Solved Examples

1. For an ideal binary liquid solutions with PA0 > PB0, which relation between XA (mole fraction of A in liquid phase) and YA (mole fraction of A in vapour phase) is correct.

(A) XA = YA

(B) XA > YA

(C) XA < YA

(D) XA / XB < YA / YB

Sol. (D).

∵ YA = (PA0 / PT) XA

∴ YA/YB = (PA0 / PB0) × (XA/XB)

∴ PA0 / PB0 > 1 (given)

⇒ YA / YB > XA / XB

2. Dry air was passed successively through a solution of 5 g solute in 180 g of water and then through pure water. The loss in weight of solution was 2.50 g and that of pure solvent is 0.04 g. The molecular weight of the solute is

(A) 31.25

(B) 3.125

(C) 312.5

(D) None

Sol. (A).

P0 - Ps ∝ loss in weight of water chamber

Ps ∝ loss in weight of solution chamber

∴ (P0 - Ps)/P0 = n / N = w / m × W / M (for very dilute solution)

0.04 / 2.54 = (5/m) / (180/18) ⇒ m = 31.25

3. The relationship between osmotic pressure at 273 K when 10 g glucose (P₁), 10 g urea (P₂) and 10 g sucrose (P₃) are dissolved in 250 ml of water is

P₁ > P₂ > P₃

P₃ > P₂ > P₁

P₂ > P₁ > P₃

P₂ > P₃ > P₁

Sol. (C).

Osmotic pressure is a colligative property and colligative property is directly proportional to concentration of solution.

In certain solvent, phenol dimerises to the extent of 60%. Its observed molecular mass in the solvent should be

> 94

< 94

= 94

unpredictable

Sol. (A).

i = Experimental colligative property / Theoretical colligative property

= 1 - α/2

= 1 - 0.6/2

= 0.7

i = Theoretical mol. mass / Observed mol. mass

Observed = 94 / 0.7

4. Assuming each salt to be 90% dissociated, which of the following will have highest osmotic pressure?

(A) decinormal Al₂(SO₄)₃

(B) decinormal BaCl₂

(C) decinormal Na₂SO₄

(D) a solution made by mixing equal volumes of (B) & (C)

Sol. (A).

The Vant Hoff factor is highest for Al₂(SO₄)₃ = 1 + (5 – 1) × 0.9 = 4.6

So, π = iCRT

5. Osmotic pressure of blood is 7.65 atm at 310 K. An aqueous solution of glucose that will be isotonic with blood is (wt./vol.)

(A) 5.41%

(B) 3.54%

(C) 4.53%

(D) 53.4%

Sol. (A).

πblood = 7.65 = C × (0.082) × 310

⇒ C = 7.65 / (310 × 0.082) = (mole/litre)

= 5.41%