Polyhydroxy aldehyde or polyhydroxy ketone or the compounds which can be hydrolysed to them are known as carbohydrates.

Types of Carbohydrates

(i) Monosaccharides: The simple carbohydrates which cannot be further hydrolysed to simpler carbohydrates. Examples: glucose and fructose

(ii) Oligosaccharides: The carbohydrates which on hydrolysis give two to nine units of monosaccharides

- Disaccharides: It gives two units of monosaccharides on hydrolysis, e.g. sucrose and maltose

- Trisaccharides: It gives three units of monosaccharides on hydrolysis, e.g. raffinose (C₁₈H₃₂O₁₆)

- Tetrasaccharides: It gives four units of monosaccharides on hydrolysis, e.g. stachyose (C₂₄H₄₂O₂₁)

(iii) Polysaccharides: These are polymeric molecules, which can be hydrolysed to give large number of monosaccharide units, e.g. (C₆H₁₀O₅)ₙ. Cellulose is a polymer containing approximately 2000–3000 glucose units per molecule

(C₆H₁₀O₅)ₙ + nH₂O → nC₆H₁₂O₆

In general, monosaccharides and oligosaccharides are crystalline solids, soluble in water and sweet in taste. These are collectively known as sugars. The polysaccharides on the other hand are amorphous, insoluble in water and tasteless and are known as non–sugars.

MONOSACCHARIDES

Carbohydrates are either monosaccharides or get converted to monosaccharides on hydrolysis. The general formula is CₙH₂ₙOₙ (n = 3 to 9).

Structure Examples:

Glucose: CH₂OH-(CHOH)₄-CHO

Fructose: CH₂OH-(CHOH)₃-CO-CH₂OH

Glyceraldehyde: CHO-CHOH-CH₂OH

Preparation of Glucose

(i) From sucrose:

C₁₂H₂₂O₁₁ + H₂O → C₆H₁₂O₆ + C₆H₁₂O₆

Sucrose → Glucose + Fructose

(ii) From starch:

(C₆H₁₀O₅)ₙ + nH₂O → nC₆H₁₂O₆

393 K, 2-3 bar, H⁺/hydrolysis

Properties of Glucose

Glucose has one aldehyde group, one primary and four secondary hydroxyl groups. It gives the following reactions:

(i) Acetylation:

CHO-(CHOH)₄-CH₂OH + (CH₃CO)₂O → CHO-(CHOH)₄-CH₂OOCCH₃

(ii) Reaction with hydroxylamine/hydrogen cyanide:

With HCN:

CHO-(CHOH)₄-CH₂OH + HCN → HO-CN-(CHOH)₄-CH₂OH

Glucose cyanohydrin With NH₂OH:

CHO-(CHOH)₄-CH₂OH + NH₂OH → HC=NOH-(CHOH)₄-CH₂OH

Glucose monooxime

(iii) Glucose reduces ammoniacal silver nitrate solution and Fehling's solution

CHO-(CHOH)₄-CH₂OH + 2Cu²⁺ → COOH-(CHOH)₄-CH₂OH + Cu₂O (Reddish brown)

CHO-(CHOH)₄-CH₂OH + Ag₂O → COOH-(CHOH)₄-CH₂OH + 2Ag

Glucose → Gluconic acid

(iv) Oxidation:

CHO-(CHOH)₄-CH₂OH + HNO₃ [O] → COOH-(CHOH)₄-COOH

Glucose → Saccharic acid

(v) Reduction:

CHO-(CHOH)₄-CH₂OH + HI (Prolonged heating) → CH₃-CH₂-CH₂-CH₂-CH₂-CH₃

Glucose → n-hexane

(vi) Reaction with phenyl hydrazine:

D–Glucose reacts with phenyl hydrazine to give glucose phenylhydrazone. If excess of phenylhydrazine is used, a dihydrazone, known as osazone is formed.

D-Glucose + C₆H₅NHNH₂ → D-Glucosazone + C₆H₅NH₂ + NH₃

(vii) Reaction with NaOH:

On heating with concentrated solution of NaOH, glucose first turns yellow, then brown and finally resinifies. However, with dilute NaOH, glucose undergoes a reversible isomerization and is converted into a mixture of D–glucose, D–mannose and D–fructose.

D-Glucose ⇌ D-Mannose ⇌ D-Fructose

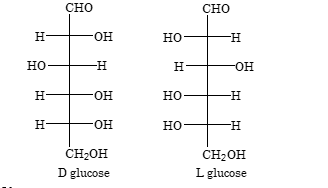

Configuration of Glucose

The Fischer projections for D– and L– glucose are shown with their stereochemical arrangements around each carbon atom.

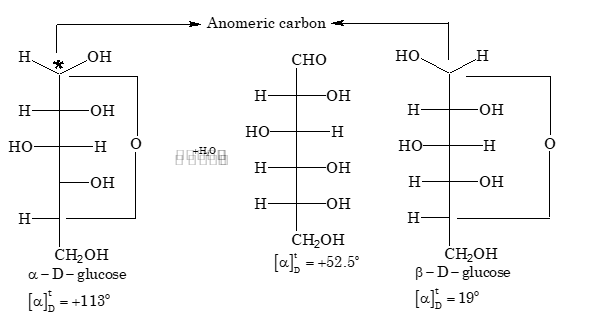

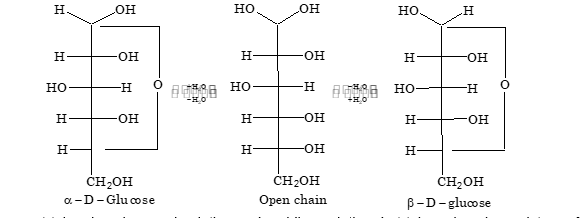

Cyclic Hemiacetal Forms of Glucose

Since methyl glucosides and other derivatives of glucose exist in two isomeric forms, therefore glucose also exists in two forms:

Key Points:

- (a) These two forms of glucose are known as anomers

- (b) The presence of hemiacetal ring confirms the absence of free –CHO group. This is the reason that glucose has no reaction with weak reagents like NH₃ and NaHSO₃

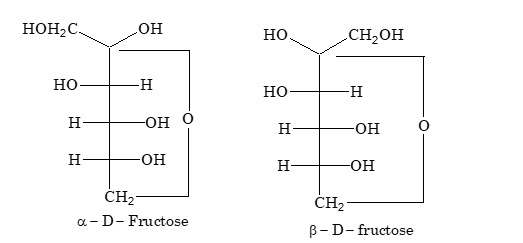

Cyclic hemiketal forms of fructose:

An increase or decrease in the value of specific rotation of an optically active compound is known as mutarotation. Mutarotation is due to interconversion of α form into β form through an open chain aldehyde form.

Hemiacetal forms of D–glucose and hemiketal forms of D–fructose are stable in the solid state but in aqueous solutions, the ring structure is opened, which results in a solution of constant specific rotation.

Mutarotation does not take place in cresol solution and pyridine solution, but takes place in a mixture of cresol and pyridine. This shows that presence of amphiprotic solvent is necessary for mutarotation.

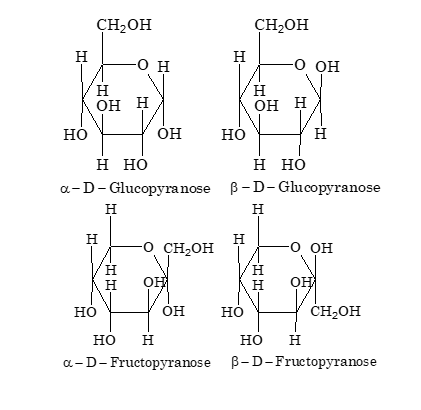

Haworth Projections

Disaccharides

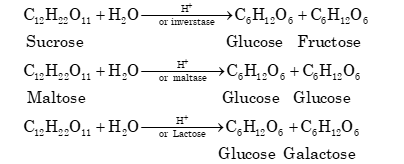

Carbohydrates which upon hydrolysis give two molecules of the same or different monosaccharides are called disaccharides, e.g. sucrose, maltose etc.

If two monosaccharide units are linked through their respective carbonyl groups, then the disaccharide is known as non–reducing, e.g. sucrose.

If the carbonyl group of any one of the two monosaccharide units is free, the disaccharide is known as reducing, e.g. maltose, lactose etc.

Common Disaccharides:

1. Sucrose:

C₁₂H₂₂O₁₁ + H₂O → C₆H₁₂O₆ + C₆H₁₂O₆

Sucrose + H⁺/invertase → Glucose + Fructose

2. Maltose:

C₁₂H₂₂O₁₁ + H₂O → C₆H₁₂O₆ + C₆H₁₂O₆

Maltose + H⁺/maltase → Glucose + Glucose

3. Lactose:

C₁₂H₂₂O₁₁ + H₂O → C₆H₁₂O₆ + C₆H₁₂O₆

Lactose + H⁺/lactase → Glucose + Galactose

Classification based on reducing property:

- Non-reducing disaccharides: If two monosaccharide units are linked through their respective carbonyl groups, then the disaccharide is known as non–reducing, e.g. sucrose

- Reducing disaccharides: If the carbonyl group of any one of the two monosaccharide units is free, the disaccharide is known as reducing, e.g. maltose, lactose etc.

Inversion of Sugar

Sucrose is dextrorotatory with specific rotation + 66.5°. On hydrolysis in the presence of HCl or enzyme invertase, it produces mixture of D(+) glucose (specific rotation +52.7°) and D(–) fructose (specific rotation = –92.4°). Since, specific rotation of D(–) fructose is greater than D(+) glucose, the resulting solution becomes laevorotatory. As hydrolysis produces a change in optical nature from dextrorotatory to laevorotatory, the process is called inversion of sugar.

Structure of Important Disaccharides

Sucrose (Non-reducing sugar):

Haworth suggested structure shows α(1→2) glycosidic linkage between glucose and fructose units

Maltose (Reducing sugar):

It is prepared by partial hydrolysis of starch by diastase enzyme:

2(C₆H₁₀O₅)ₙ + nH₂O → nC₁₂H₂₂O₁₁

Starch + Diastase → Maltose

On hydrolysis, one mole of maltose gives two moles of D–glucose. It is a reducing sugar.

The two glucose units are linked through a α(1→4) glycosidic linkage between C–1 of one unit and the C–4 of another unit. Both glucose units are in pyranose form.

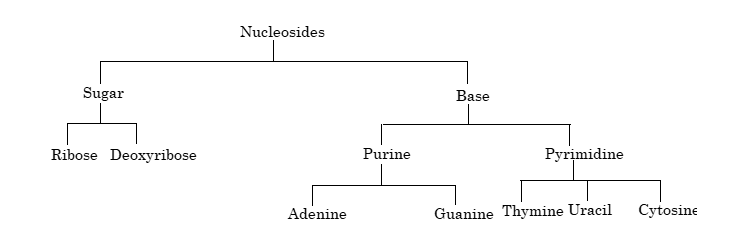

NUCLEIC ACIDS

Nucleic acids are colourless compounds containing the elements carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen and phosphorus.

Nucleic acid → Nucleotides → Nucleosides + Phosphoric acid

(NH₃, 115°C) (NH₃, 175°C)

Differences between RNA and DNA:

| Property | RNA (Ribose nucleic acid) | DNA (Deoxyribose nucleic acid) |

| Location | It occurs in cytoplasm | It is found inside the nucleus |

| Structure | It exists either as single helix or as a double helix | It always exists as double helix |

| Sugar | Sugar is ribose type | Sugar is of deoxyribose type |

| Function | It helps in protein synthesis | It carries genetic continuity |

| Bases | Bases are uracil, cytosine, adenine, guanine | Bases are thymine, cytosine, adenine, guanine |

AMINO ACIDS

The class of organic compound containing both the carboxyl, COOH, and the amino, NH₂ group. These have general formula R-CHNH₂-COOH

Two naturally occurring amino acids differ only in the side chain, R. All amino acids except glycine (H₂N-CH₂-COOH), have a centre of asymmetry at the α position.

Types of Amino Acids

Based on functional groups:

- Neutral: It contains equal number of NH₂ and COOH groups

- Acidic: It contains more COOH groups than NH₂ groups

- Basic: It contains more NH₂ groups than COOH groups

Based on synthesis in body:

- Essential amino acids: which cannot be synthesized in the body. It is supplied through diet

- Non–essential amino acids: which are synthesized in the body

Illustration 1:

Question: One of the essential amino acids is

(A) lysine

(B) glycine

(C) serine

(D) proline

Solution: (A) lysine

Preparation of Amino Acids

(i) By reaction of an α-halogen substituted acid with conc. NH₃:

H₃C-CHCl-COOH + 2NH₃ → H₃C-CHNH₂-COOH + NH₄Cl

→ Alanine

(ii) Strecker's synthesis:

The reaction between cyanohydrin and conc. NH₃ followed by hydrolysis.

R-CHOH-CN + HNH₂ → R-CHNH₂-CN + H₂O → R-CHNH₂-COOH + 2H₂O

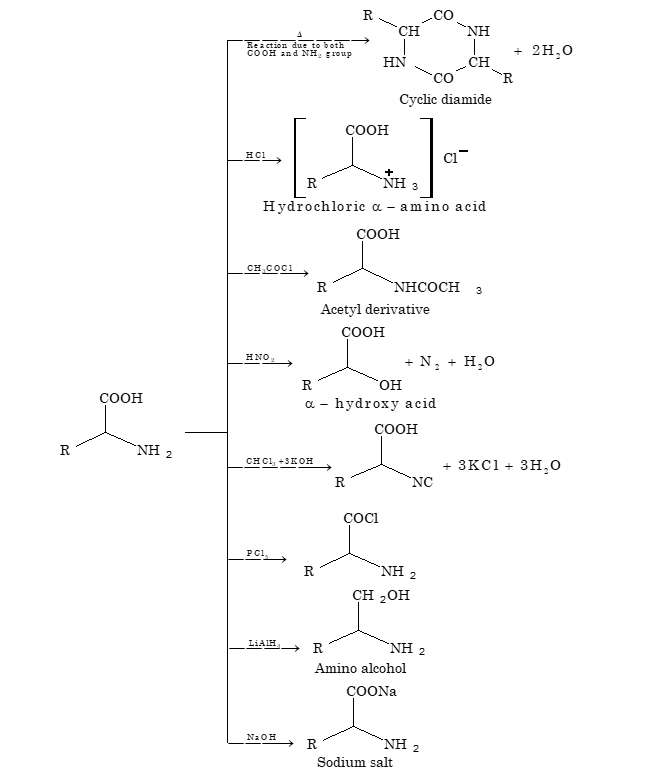

Properties of Amino Acids

(i) Physical Properties: The amino acids are crystalline solids with high melting point and dipole moment.

(ii) Zwitterion Formation: They are soluble in polar solvents. They exist as dipolar species called zwitterions.

R-CHNH₂-COOH ⇌ R-CHNH₃⁺-COO⁻

Amino acid ⇌ Zwitterion

(iii) Isoelectric Point:

In acidic medium, the amino acid exists as cation and moves towards the negative electrode while in basic medium, the amino acid exists as anion and moves towards the positive electrode. The pH at which this dipolar ion stops moving towards the respective electrodes is known as isoelectric point.

At isoelectric point the amino acids have the least solubility in water.

(v) Peptides:

Peptides are the organic molecules with –CONH– linkage. Such a linkage is formed by removal of water molecule from the carboxyl group of one amino acid and the α amino group of the other in the presence of strong condensing agents.

R₁-CHNH₂-COOH + R₂-CHNH₂-COOH → R₁-CHNH₂-CO-NH-CHR₂-COOH + H₂O

(Cyclic diamide formation)

The peptides can be separated on the basis of their ionization behaviour. Peptides can be hydrolysed by boiling with either strong acid or base to give the constituent amino acids in free form.

CHEMISTRY IN ACTION

Dyes are natural or synthetic compounds which are used for imparting permanent colour to fabrics, food and other substances for their beautification.

Classification of Dyes Based on their Constitution

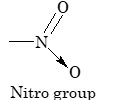

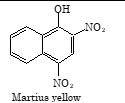

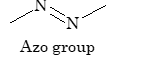

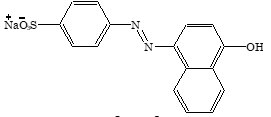

| Type | Structural unit | Examples |

| Nitro dyes |

-NO₂ (Nitro group) |

Martius yellow |

| Azo dyes |

-N=N- (Azo group) |

Orange I |

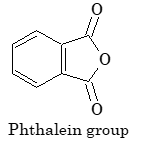

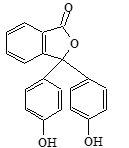

| Phthalein dyes |

Phthalein group |

Phenolphthalein |

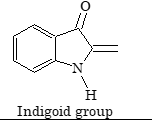

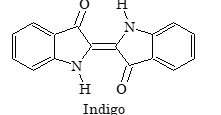

| Indigoid dyes |

Indigoid group |

Indigo |

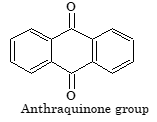

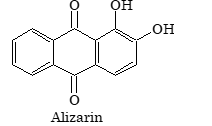

| Anthraquinone dyes |

Anthraquinone group |

Alizarin |

Illustration 2:

Question: Alizarin gives red colour by mordanting it with the sulphate of a metal. The metal ion is

(A) Ba²⁺ (B) Al³⁺ (C) Cr³⁺ (D) Fe³⁺

Solution: (B). With Al³⁺ ions, alizarin gives red colour.

Classification of Dyes on the Basis of Application

(i) Acid dyes: These are generally salts of sulphonic acids and may also contain carboxylic or phenolic group. These don't have affinity for cotton but are applied to wool, silk and nylon.

Examples: Orange–I and Orange–II, which can be obtained by coupling of diazotized sulphanilic acid with α and β–naphthol.

(ii) Basic dyes: These contain amino group or dialkyl amino group as chromophore or auxochrome. In acidic solution they form water–soluble cations and react with anionic sites present on the fabrics to fix themselves.

Examples: aniline yellow, butter yellow, malachite green. They are used to dye nylons, polyesters, wool etc.

(iii) Direct dyes: These are directly applied to the fabrics from an aqueous solution. These are attached to the fabric through hydrogen bonding and used to dye cotton, rayon, wool, silk etc.

Examples: martius yellow and congo red.

(iv) Disperse dyes: These dyes, as the name implies consists of minute particles which are dispersed or spread from a suspension into the fabric. These are used for polyesters, nylon and polyacrylonitrile.

Examples: celliton fast blue B and celliton fast pink B.

(v) Vat dyes: These are water insoluble dyes, which are reduced to colourless soluble form by alkaline reducing agents like NaHSO₃ and applied to the fabrics and then oxidized to the insoluble dye when exposed to air or an oxidizing agent.

Example: Indigo is common example of vat dyes.

(vi) Mordant dyes: These are the dyes which are applied to the fabric after treating it with a metal ion. The metal ion binds to the fabric and the dye in turn is co–ordinated to the metal ion known as mordant. The colour of the same dye varies with the different metal ions used, e.g. alizarin with aluminium ion is rose red while with barium ion it is blue in colour. These dyes are usually applied for dyeing wool.

Chemicals in Medicines

The branch of science that deals with the treatment of diseases by using suitable chemicals is called chemotherapy.

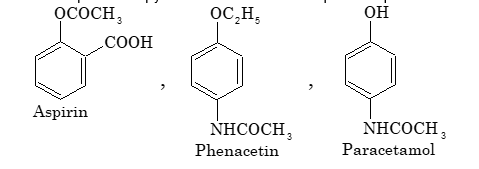

(i) Antipyretics: These are the chemicals which are used to bring down the body temperature in high fever, but their use often leads to perspiration.

Aspirin is a common example of antipyretic. Some other examples are phenacetin and paracetamol.

(ii) Analgesics: These are chemicals, which are used for relieving pain. Aspirin and certain other antipyretics also act as analgesics. Some narcotics which produce sleep and unconsciousness like morphine, marijuana, heroin, codeine also act as analgesics.

(iii) Antiseptics: These are the chemicals, which are used to kill or prevent the growth of micro organism. These are not harmful to living tissues and can be applied to wounds, cuts or diseased skin surface. Iodine is a powerful antiseptic. It is used as tincture of iodine (2–3% I₂ solution in alcohol–water mixture). Organic dyes like gentian violet and methylene blue are also used as effective antiseptics.

(iv) Tranquillizers: These are chemicals, which are used for treatment of mental diseases. These are also called psychotherapeutic drugs. These are the constituents of sleeping pills and act on higher centres of central nervous system. Barbituric acid and its derivatives are used as tranquilizers for a long time. Equanil is another tranquilizer which is used in depression and hypertension.

(v) Antibiotics: These are chemical substances produced by micro organism, which prevent the growth or even destroy other micro organisms, e.g. penicillin is very effective drug in case of pneumonia, bronchitis, sore throat and abscesses. Streptomycin is used for tuberculosis and chloramphenicol for typhoid.

(vi) Sulpha drugs: They also act against micro organisms just like antibiotics, e.g. sulphanilamide, Sulphadiazine and sulphaguanidine etc.

Sulphadiazine: H₂N-SO₂NH-N-N (pyrimidine ring)

Illustration 3:

Question: Which of the following set of reactants is used for preparation of paracetamol from phenol?

(A) HNO₃, H₂/Pd, (CH₃CO)₂O

(B) H₂SO₄, H₂/Pd, (CH₃CO)₂O

(C) C₆H₅N₂Cl, SnCl₂/HCl, (CH₃CO)₂O

(D) Br₂/H₂O, Zn/HCl, (CH₃CO)₂O

Solution: (A)

OH → [HNO₃] → OH-NO₂ → [H₂/Pd] → OH-NH₂ → [(CH₃CO)₂O] → OH-NHCOCH₃ (Paracetamol)

Chemistry of Rocket Propellants

The chemical substances (fuel) used to propel a rocket are known as rocket propellants. The constituents of a propellant may be a solid, a liquid or a gas. Depending upon the physical state, the propellants are classified into following types:

(i) Solid propellants:

The most common solid propellant is composite propellant, which is a mixture of polymeric binder like polyurethane or polybutadiene as fuel and ammonium perchlorate as an oxidizing agent along with an additive like finely divided Al or Mg to modify the working of the propellant.

Another widely used solid propellant is double–base propellant, which is made up of nitro glycerine and nitrocellulose. Solid propellants once ignited will burn with a predetermined rate and their ignition cannot be stopped.

(ii) Liquid propellants:

These consists of a mixture of kerosene oil (alcohol hydrazine or liquid H₂) as fuel and liquid O₂ (liquid N₂O₄ or nitric acid) as an oxidizing agent. These bi–liquid propellants give higher thrusts than solid propellants and their ignition can be controlled by controlling the flow of the liquid propellant.

In some cases, a single chemical compound, known as monopropellants acts both as oxidizer and fuel, e.g. methyl nitrate, nitromethane and H₂O₂.

(iii) Hybrid propellants:

These propellants consist of a solid fuel like acrylic rubber and a liquid oxidizer like liquid N₂O₄.

Exercise 1: The propellants used in SLV–3 is

(A) solid

(B) liquid

(C) solid–liquid

(D) biliquid

Relation Between the Specific Impulse and Critical Temperature

The relation between the specific impulse of a propellant and the critical temperature attained in a rocket blast is as follows:

Specific impulse (Iₛ) = √(Tc/M̄)

where, Tc is the critical temperature inside the rocket motor and M̄ is the average molecular mass of the gases coming out of the rocket nozzle.

The energy of propellant is measured in terms of its specific impulse. Higher the value of Iₛ, the better is the propellant (from energy point of view).

Polymers

Polymers (in Greek, poly = many and meros = parts) are very high molecular mass substances each molecule of which consists of a very large number of simple structural units joined together by covalent bonds in regular fashion.

The simple molecules, which on repetition form the polymers are called monomers and the process by which these simple molecules join to convert monomers into polymers is called polymerization.

A polymer may be made by polymerization of a large number of one or more compounds, e.g. polyethylene is made from ethylene (ethene) but nylon–66 is made from H₂N–(CH₂)₆–NH₂ (hexamethylene diamine) and HOOC–(CH₂)₄–COOH (adipic acid).

Polymers and Macromolecules

The terms polymers and macromolecules are often used without any distinction. But strictly speaking, a polymer always consists of hundreds to thousands of repeating structural units but a macromolecule may or may not contain repeating structural units.

For example, proteins and nucleic acids should be regarded as macromolecule but not polymer since their molecules do not contain repeating structural units. In contrast, polythene may be regarded both as a macromolecule as well as a polymer since it contains a large number of repeating structural units.

Thus, all polymers are macromolecules but all macromolecules are not polymers.

Homopolymers and Copolymers

Depending upon the nature of the repeating structural units, polymers are divided broadly into two categories:

1. Homopolymers:

Polymers whose repeating structural units are derived from only one type of monomer units are called homopolymers. For example, polyethylene, polyvinyl chloride (PVC), neoprene etc.

nCH₂=CH₂ → [Polymerization] → (CH₂–CH₂)ₙ

Ethylene (Monomer) Polyethylene (Polymer)

2. Copolymers:

Polymers which are synthesized by polymerization of two or more types of monomer units are called copolymers. For example, nylon–66, styrene butadiene rubber, bakelite etc.

nH₂N–(CH₂)₆–NH₂ + nHOOC–(CH₂)₄–COOH

Hexamethylene diamine(monomer) Adipic acid(monomer)

↓ [Polymerization] + nH₂O

[NH–(CH₂)₆–NH–CO–(CH₂)₄–CO]ₙ

Nylon 66

Classification of Polymers

Classification based on Source of Availability

(i) Natural polymers: Polymers which are found in nature, i.e. animals and plants are called natural polymers. For example, proteins, nucleic acid, cellulose, rubber etc.

(ii) Semisynthetic polymers: These are mostly derived from naturally occurring polymers by chemical modification. For example, cellulose on acetylation with acetic anhydride forms cellulose diacetate, which is used in making threads and materials like films, glasses etc.

Vulcanized rubber which is superior to natural rubber is used for making tyres. Gun cotton, which is cellulose trinitrate is used in making explosives.

(iii) Synthetic fibres: A large number of man–made polymers are now available. These includes fibres, plastics and synthetic rubbers etc. and find diverse uses as in clothing, electric fitting, eye lenses, substitute for wood and metals.

Illustration 4:

Question: Which of the following is a natural polymer?

(A) Polyester (B) Glyptal (C) Starch (D) Nylon–6

Solution: (C)

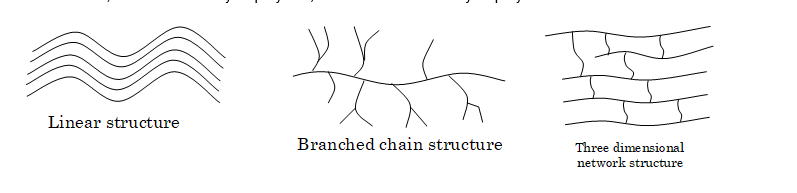

Classification Based on Structures

(i) Linear polymers: In these polymers, the monomers are joined together to form long straight chains of polymer molecules. The various polymeric chains are then stacked over one another to give a well packed structure. Because of the close packing of polymer chains, linear polymers have high melting points, high densities and high tensile (pulling) strength, e.g. polythene, nylon, polyesters etc.

(ii) Branched chain polymers: In these polymers, the monomer units not only combine to produce the linear chain (called the main chain) but also form branches of different lengths along the main chain. As a result of branch chain, the molecules do not pack well and therefore have lower melting points, densities and tensile strength, e.g. amylopectin, glycogen etc.

(iii) Three dimensional network polymers: In these polymers, the initially formed linear polymer chains are joined together by cross links to form a three dimensional network structure. Because of the cross links, these polymers are also called cross linked polymers. These polymers are hard, rigid and brittle, e.g. bakelite, urea–formaldehyde polymer, melamine–formaldehyde polymer etc.

Classification Based on Mode of Polymerization

(i) Addition polymers: Addition polymers are formed by reactions between monomer molecules possessing multiple bonds. Here, the molecular formula of the repeating structural unit is same as that of the starting monomer. For example, polythene by addition of ethylene molecules, styrene butadiene rubber by addition of butadiene and styrene molecules.

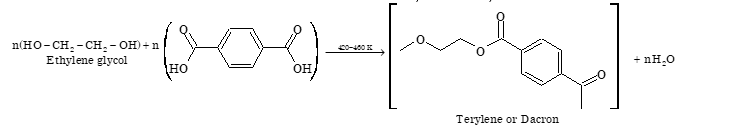

(ii) Condensation polymers: The condensation polymers are formed by condensations between monomeric units with the elimination of small molecules such as water, ammonia, alcohol etc.

Classification Based on Molecular Forces

Polymers have been classified into the following four categories on the basis of the magnitude of intermolecular forces such as (van der Waal's forces, hydrogen bonds and dipole–dipole interactions) present in them.

1. Elastomers: Polymers in which the intermolecular forces of attraction between the polymer chains are the weakest are called elastomers. Examples are vulcanized rubber, Buna–S etc.

2. Fibres: Polymers in which the intermolecular forces of attraction are the strongest are called fibres. Examples are nylon, terylene etc.

3. Thermoplastics: Polymers in which the intermolecular forces of attraction are in between those of elastomers and fibres are called thermoplastics. Examples are polythene, polypropylene, polystyrene, PVC etc.

4. Thermosetting polymers: These are semi–fluid substances with low molecular weights which when heated in a mould, undergo change in chemical composition to give a hard, infusible and insoluble mass. Examples are phenol–formaldehyde (bakelite), urea–formaldehyde etc.

Exercise 2

A polymer which is used for making ropes and carpet fibres is

(A) polyacetylene (B) polypropylene (C) polyacrylonitrile (D) PVC

Illustration 5:

Question: Polymeric molecules are held by

(A) interatomic forces (B) coulombic forces (C) intermolecular forces (D) gravitational forces

Solution: (C)

Exercise 2: A polymer which is used for making ropes and carped fibres is

(A) polyacetylene

(B) polypropylene

(C) polyacrylonitide

(D) PVC

General Methods of Preparation

The two general methods used for preparing polymers are addition and condensation polymerization.

Addition Polymerization

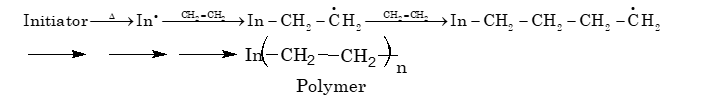

When the molecules of same monomer or different monomers simply add together to form a polymer, this process is called additional polymerization. The monomers used here are unsaturated compounds such as alkenes, alkadienes and their derivatives. This process is also called chain growth polymerization because it takes place through stages leading to increase of chain length and each stage produces reactive intermediate for use in the next stage of the growth of the chain.

(i) Free radical addition polymerization:

A variety of unsaturated compounds, alkenes or dienes and their derivatives are polymerized by this process. For example, polymerization of ethylene takes place through radicals, which are generated by an initiator. These initiators are molecules which decompose easily to provide radicals. Tert–butyl peroxide and benzyl peroxides are commonly used as initiators.

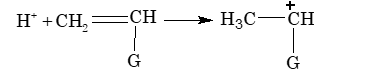

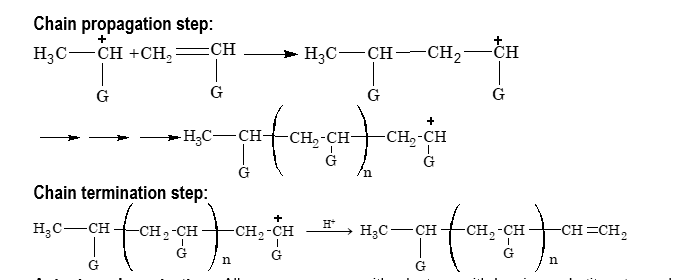

(ii) Cationic polymerization:

Certain alkene monomers can be polymerized by a cationic mechanism as well as by a free radical mechanism. Cationic polymerization, like free radical polymerization, occurs by a chain reaction pathway in presence of strong protic acids such as H₂SO₄ or Lewis acids such as AlCl₃, BF₃ etc. in presence of trace of water as initiator.

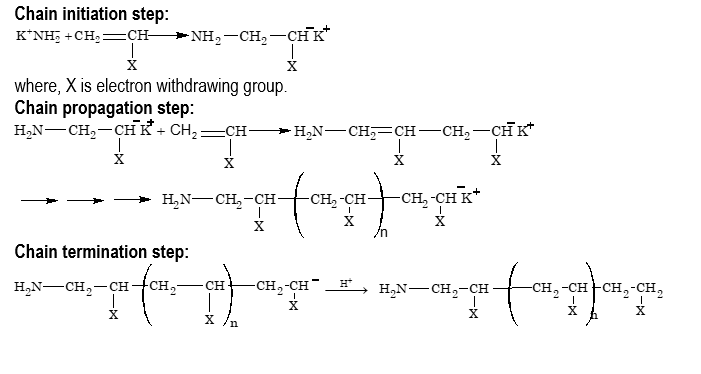

Chain initiation step:

where, G is an electron donating group.

(iii) Anionic polymerization:

Alkene monomers with electron withdrawing substituents such as C₆H₅, CN, COOR etc. can be polymerized by an anionic mechanism as well as by a free radical mechanism. Anionic polymerization, like free radical polymerization, occurs by a chain reaction pathway in presence of strong bases such as Na, K, K⁺NH₂⁻, Li⁺NH₂⁻ etc., or organometallic compounds such as n–butyl lithium as initiators.

Condensation Polymerization

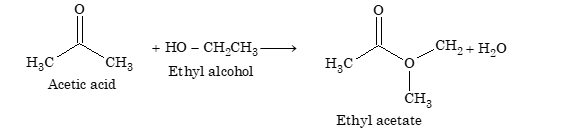

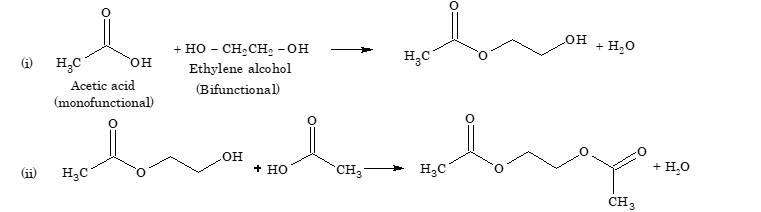

If two reacting molecules have one functional group each, the reaction stops after one step. For example, acetic acid reacts with ethyl alcohol to form ethyl acetate in one step.

If, however, one of the reacting molecule has two functional groups and the other has one functional group, i.e. acetic acid and ethylene glycol, the reaction stops after two steps.

However, when both the reactants have two functional groups each, they undergo a series of condensation reactions in a controlled stepwise manner with elimination of water molecules to form polymers.

Illustration 6:

Question: Nylon–66 is a polyamide of

(A) vinylchloride and formaldehyde (B) adipic acid and methylamine

(C) adipic acid and hexamethylene diamine (D) formaldehyde and melamine

Solution: (C)

HO–CO–(CH₂)₄–CO–OH + H₂N–(CH₂)₆–NH₂

→ [–CO–(CH₂)₄–CO–NH–(CH₂)₆–NH–]ₙ

Nylon-66

Exercise 3

Bakelite is obtained from phenol by reacting it with

(A) acetaldehyde (B) acetal (C) formaldehyde (D) chlorobenzene

SOME POLYMERS AND THEIR USES

Some important polymers and their uses along with their monomeric units are given in the following table:

| S. No. | Polymers | Monomer | Uses |

| 1. | Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) | Vinyl chloride (CH2 = CH – Cl) | Food wrapping fibres, also used for making shower curtains, shoe soles etc. |

| 2. | Polytetrafluoro ethylene (Teflon) | Tetrafluoro ethylene (CF2 = CF2) | For making non–stick utensil, gaskets, pump packing etc. |

| 3. | Polystyrene | Styrene (Ph – CH = CH2) | In the manufacture of lenses, light covers, light shades etc. |

| 4. | Nylon–66 | Adipic acid and hexamethylenediamine | For making fibres, carpets etc., as a substitute for metals in bearings and gears. |

| 5. | Terylene or Dacron | Ethylene glycol and terephthalic acid | Fibres of terylene are used for the manufacture of wash and wear fabrics, tyre cords, seat belts etc. |

| 6. | Bakelite | Phenol and formaldehyde | As binding glue for laminated wooden planks and in varnishes and lacquers. |

Illustration 7: Which of the following is not a biopolymer?

(A) Proteins

(B) Nucleic acids

(C) Cellulose

(D) Neoprene

Solution: (D).

Exercise 4: Suppose group (A) in the compound CH2 = CH – A, is say –Cl or –CN or –COOC2H5, then corresponding polymer would be respectively

(A) PAN, PVA, PMMA

(B) PVC, PAN, poly ethyl acrylate

(C) PAN, PVA, PVE

(D) None of the above

ANSWER TO EXERCISE

Exercise 1: A

Exercise 2: B

Exercise 3: C

Exercise 4: B

Solved Examples

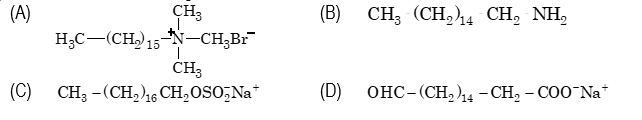

- Which one of the following is not a surfactant?

Sol. (B). A surfactant has both acidic as well as basic groups.

- Which of the following does not behave as a surfactant?

(A) Soap

(B) Detergent

(C) Phospholipid

(D) Triglycerides

Sol. (D). Triglycerides do not have polar heads and non–polar tails and hence do not behave as surfactants.

- Which of the following are monoliquid propellants?

(A) H2O2

(B) CH3ONO2

(C) CH3NO2

(D) All of the above

Sol. (D).

- A hybrid propellant uses

(A) a solid fuel and a liquid oxidizer

(B) a composite solid propellant

(C) a biliquid propellant

(D) a monoliquid propellant

Sol. (A).

A solid fuel and a liquid oxidizer.

- Which of the following is an azo dye?

(A) Orange–1

(B) Malachite green

(C) Indigo

(D) Martius yellow

Sol. (A). Orange–1 is an azo dye.

- Which of the following group is not an auxochrome?

Sol. (D).

- The base of talcum powder is

(A) chalk

(B) magnesium hydrosilicate

(C) sodium aluminium silicate

(D) zinc stearate

Sol. (B).

- Which of the following is not an auxochrome?

(A) OH

(B) NH2

(C) OCH3

(D) SO3H

Sol. (D).

- Which of the following is a synthetic polymer?

(A) Cellulose

(B) PVC

(C) Proteins

(D) Nucleic acids

Sol. (B).

- Which of the following is not a condensation polymer?

(A) Glyptal

(B) Nylon–66

(C) Dacron

(D) PTFE

Sol. (C).