Comprehensive Guide to Atoms, Nuclei, and Radioactivity in Physics

The study of atomic nuclei and radioactive phenomena represents one of the most significant breakthroughs in modern physics. Since Henri Becquerel's groundbreaking discovery of radioactivity in 1896, our understanding of nuclear processes has revolutionized both theoretical physics and practical applications, from medical imaging to nuclear energy production.

What is Radioactivity and How Was It Discovered?

Radioactivity is the spontaneous emission of radiation from unstable atomic nuclei. Becquerel discovered this phenomenon when studying minerals like pitchblende, observing that they could blacken photographic plates even when wrapped in light-proof paper. This intrinsic property of certain atoms occurs independently of external conditions like temperature, pressure, or chemical combinations, indicating that radioactivity originates from within the atomic nucleus itself.

The radiation emitted from radioactive substances consists of three distinct types: alpha (α) rays, beta (β) rays, and gamma (γ) rays. Each type possesses unique characteristics that determine their behavior and applications in various fields.

Types of Radioactive Emissions and Their Properties

Alpha Particles (α)

Alpha particles are helium nuclei (2He4) carrying a positive charge of +2e and having approximately four times the mass of a hydrogen atom. These particles travel at 5-7% of light speed, possess high ionizing power but limited penetrating ability, being stopped by just a few centimeters of air or thin aluminum foil.

Beta Particles (β)

Beta particles are high-speed electrons with greater penetrating power than alpha particles but lower ionizing capability. Unlike alpha particles, beta particles exhibit a continuous energy spectrum, with energies ranging from a minimum to maximum value. Their velocities approach the speed of light.

Gamma Rays (γ)

Gamma rays are electromagnetic waves with wavelengths around 10-12 meters, providing maximum penetrating power while having minimal ionizing effect. These rays result from nuclear transitions between excited energy states and can penetrate several meters of air or significant thicknesses of lead.

The Nuclear Structure and Its Components

The atomic nucleus contains the entire positive charge and nearly all the atomic mass, with electrons orbiting this dense central core. Nuclei consist of protons (positively charged particles) and neutrons (electrically neutral particles), collectively called nucleons.

The atomic number (Z) represents the number of protons in a nucleus, while the mass number (A) equals the total number of nucleons. Isotopes are nuclides with identical proton numbers but different neutron counts, whereas isobars have the same mass number but different atomic numbers.

Radioactive Decay Law and Mathematical Framework

Radioactive decay follows a fundamental statistical law: the number of atoms disintegrating per second is directly proportional to the number of atoms present at that instant. This relationship is expressed mathematically as:

where λ represents the decay constant. The solution to this differential equation yields the exponential decay formula:

The activity of a radioactive substance is defined as:

Half-life and Mean Life

The half-life (t₁/₂) is the time required for half the radioactive nuclei to decay:

The mean life (τ) represents the average lifetime of radioactive nuclei:

Nuclear Binding Energy and Mass Defect

One of the most profound concepts in nuclear physics is mass defect - the difference between the mass of a nucleus and the sum of its constituent nucleons when free. This "missing" mass converts to binding energy according to Einstein's mass-energy equivalence principle.

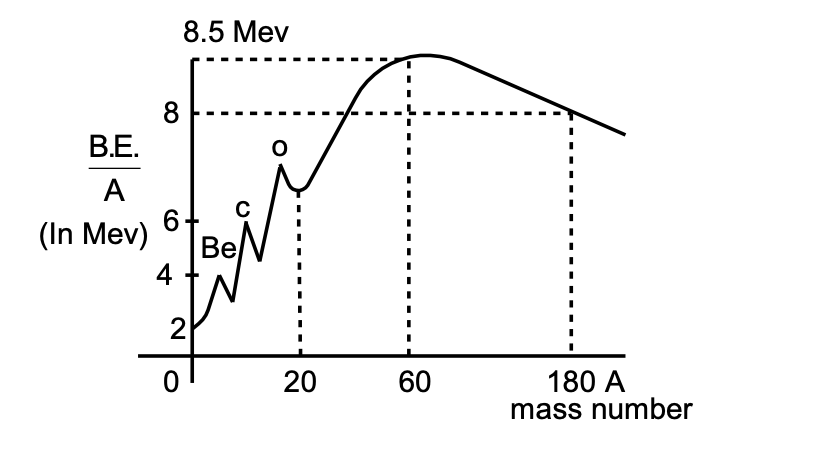

The binding energy per nucleon varies with mass number, reaching maximum values around A = 50-80, explaining why nuclei in this range exhibit maximum stability. This relationship underlies both nuclear fission and fusion processes.

Nuclear Forces: The Strongest Force in Nature

Nuclear forces represent the strongest known forces in nature, binding protons and neutrons within the nucleus despite electromagnetic repulsion between positively charged protons. These forces operate over extremely short ranges (approximately 10-15 meters) and exhibit charge independence - the nuclear force between any two nucleons remains essentially identical regardless of their charge state.

Nuclear Reactions: Fission and Fusion

Nuclear Fission

Nuclear fission involves the splitting of heavy nuclei into lighter fragments, releasing tremendous energy. The most common fission reaction occurs when slow neutrons strike uranium-235:

Nuclear Fusion

Nuclear fusion combines light nuclei into heavier ones, releasing even more energy per unit mass than fission. A typical fusion reaction is:

Essential Nuclear Physics Formulas

| Formula Name | Mathematical Expression | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Radioactive Decay | N(t) = N₀e-λt | Number of nuclei remaining after time t |

| Activity | A(t) = λN(t) = A₀e-λt | Rate of radioactive decay |

| Half-life | t₁/₂ = ln(2)/λ ≈ 0.693/λ | Time for half the nuclei to decay |

| Mean Life | τ = 1/λ | Average lifetime of radioactive nuclei |

| Mass Defect | Δm = Z·mp + (A-Z)·mn - M(Z,A) | Mass difference in nuclear binding |

| Binding Energy | BE = Δm·c² | Energy equivalent of mass defect |

| Q-value | Q = Δm × 931 MeV | Energy released in nuclear reactions |

| Nuclear Radius | R = r₀A1/3 | Nuclear radius (r₀ ≈ 1.2 fm) |

| Alpha Decay | ZXA → Z-2YA-4 + 2He4 | Alpha particle emission |

| Beta Decay | ZXA → Z+1YA + e- + ν̄e | Beta-minus decay with antineutrino |

Displacement Laws of Radioactivity

The Rutherford-Soddy displacement laws describe the changes occurring during radioactive decay:

Alpha Decay Rule

During α decay, the daughter element is two positions below the parent in the periodic table, with mass number reduced by 4 units.

Beta Decay Rule

During β⁻ decay, the daughter nucleus has the same mass number but atomic number increased by 1.

Gamma Decay Rule

γ emission results in no change of atomic number or mass number, only energy state transitions.

Units of Radioactivity

Becquerel (Bq): 1 disintegration per second

Curie (Ci): 3.7 × 10¹⁰ disintegrations per second

Rutherford: 10⁶ disintegrations per second

Applications and Modern Relevance

Understanding nuclear physics principles enables numerous technological applications, from medical radioisotopes and imaging techniques to nuclear power generation and research tools. The concepts of radioactive decay underpin carbon dating methods, while nuclear binding energy calculations inform reactor design and safety protocols.

Modern applications include:

- Medical Physics: PET scans, cancer treatment, radiopharmaceuticals

- Nuclear Energy: Power generation, reactor design, waste management

- Archaeological Dating: Carbon-14 dating, potassium-argon dating

- Industrial Applications: Non-destructive testing, sterilization

- Research: Particle accelerators, nuclear structure studies

This comprehensive foundation in atomic and nuclear physics provides essential knowledge for advanced studies in modern physics, engineering applications, and emerging technologies in nuclear medicine and energy production.

Improtant Note: Nuclear physics combines fundamental particle interactions with practical applications that benefit society. From the discovery of radioactivity to modern nuclear medicine and clean energy research, understanding these principles continues to drive technological advancement and scientific discovery.

Radioactivity

It was observed by Henri Becquerel in i896 that some minerals like pitchblende emit radiation spontaneously, and this radiation can blacken photographic plates if photographic plate is wrapped in light proof paper. He called this phenomenon radioactivity. It was observed that radioactivity was not affected by temperature, pressure or chemical combination, it could therefore be a property that was intrinsic to the atom-more specifically to its nucleus. Detailed studies of radioactivity resulted in the discovery that radiation emerging from radioactive substances were of three types : -rays, -rays and -rays.

-rays were found to be positively charged, -rays (mostly) negatively charged, and - rays uncharged. Some of the properties of and – rays, are explain below:

(i) Alpha Particles: An a-particle is a helium nucleus, i.e. a helium atom which has lost two electrons. It has a mass about four times that of a hydrogen atom and carries a charge +2e. The velocity of a-particles ranges from 5 to 7 percent of the velocity of light. These have very little penetrating power into a material medium but have a very high ionising power.

(ii) Beta Particles: b-particles are electrons moving at high speeds. These have greater (compared to a-particles) penetrating power but less ionising power. Their emission velocity is almost the velocity of light. Unlike a-particles, they have a spectrum of energy, i.e., beta particles possess energy from a certain minimum to a certain maximum value.

(iii) Gamma Rays: g-rays are electromagnetic waves of wavelength of the order of ~ 10–12 m. These have the maximum penetrating power (even more than X–ray) and the least ionising power. These are emitted due to transition of excited nucleus from higher energy state to lower energy state.

Property

α

- Nature: Positively charged particles, ₂He⁴ nucleus

- Charge: +2e

- Mass: 6.6466 × 10⁻²⁷ kg

- Range: ~10 cm in air, can be stopped by 1 mm of Al

- Natural sources: By natural radioisotopes e.g. ₉₂U²³⁶

β

- Nature: Negatively charged particles (electrons)

- Charge: –e

- Mass: 9.109 × 10⁻³¹ kg

- Range: Up to a few m in air, can be stopped by ~cm of Al

- Natural sources: By radioisotopes e.g. ₂₉Co⁶⁸

γ

- Nature: Uncharged, λ ~ 0.01 Å, electromagnetic radiation

- Charge: 0

- Mass: 0

- Range: Several m in air, stopped by ~ cm of Pb

- Natural sources: Excited nuclei formed as a result of α, β decay

Rutherford-Soddy displacement laws

-

During an α decay, the daughter element was always two positions below the parent in the periodic table; the mass number of the daughter nucleus was 4 units smaller than that of the parent nucleus.

Xba→Yb-4a-2+α

- During β-decay, the daughter nucleus had the same mass number as the parent while its atomic number was greater than that of the parent by 1 (smaller by 1 unit in β⁺ decay).

Xba→Yba+1+β - γ emission did not result in change of atomic number or mass number.

Note: Radioactivity is observed to be a random process; it cannot be predicted when a particular nucleus will decay. One can only discuss the probability of its decay.

2. RADIOACTIVE DECAY LAW

The number of atoms disintegrating per second dN dt is directly proportional to the number of atoms (N) present at that instant. For most radioisotopes, λ is very small in the SI system. It takes a large number N (~ Avogadro number, 1023) to get any significant activity.

dNdt = -λN ....(i)

Where λ is the radioactivity decay constant.

If N0 is the number of radioactive atoms present at a time t = 0, and N is the number at the end of time t, then:

N = N0 e-λt

The term dN dt is called the activity of a radioactive substance and is denoted by 'A'.

Units:

- 1 Becquerel (Bq) = 1 disintegration per second (dps)

- 1 curie (Ci) = 3.7 × 1010 dps

- 1 Rutherford = 106 dps

The changes in N, due to radioactivity, are very small in 1 s compared with the value of N itself. Therefore, N may be approximated by means of a continuous function N(t).

For the case considered in equation (i), we can write:

A = rate of decrease of N = λN

or

-dNdt = λN ....(ii)

Note: the equation (ii) is valid only for large value of N, typically ~1018 or so.

If the number of atoms at time t = 0 (initial) is N = N0, then one can solve equation (ii):

∫N0NdNN = - ∫0t λ dt

or

ln(N/N0) = -λt

or

N(t) = N0 e-λt ....(iii)

The activity A(t) = λN(t) and is given by

A(t) = λN0 e-λt

= A0 e-λt taking (A0 = λN0) ....(iv)

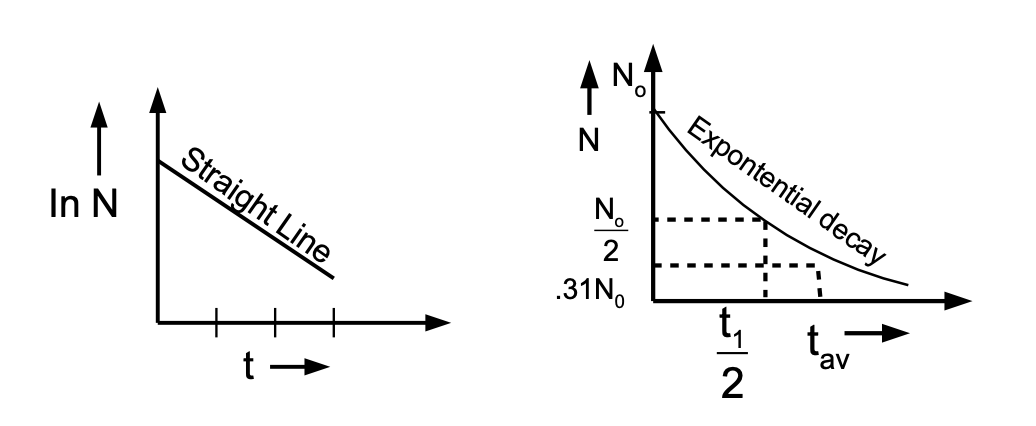

The variation of N is represented below:

Graphs of A vs t or In A vs t are similar to the above graphs

HALF-LIFE

A significant feature of the above graph is the time in which the number of active nuclei (N) is halved. This is independent of the starting value, N = N0. Let us compute this time:

N02=N0e-λt'

∴e-λt'=12

or,

λt' = ln 2 = 0.693 (approx)

or,

t' = T12 = 0.693λ

This half-life represents the time in which the number of radioactive nuclei falls to 1⁄2 of its starting value. Activity, being proportional to the number of active nuclei, also has the same half-life.

MEAN-LIFE

A very significant quantity that can be measured directly for small numbers of atoms is the mean lifetime. If there are n active nuclei, (atoms) (of the same type, of course), the mean life is:

τ¯=τ1 + τ2 + … + τnn

Where τ1, τ2, …, τn represent the observed lifetime of the individual nuclei and n is a very large number. It can also be calculated as a weighted average:

τ¯=τ1N1 + τ2N2 + … + τnNn N1 + … + Nn

Where:

N1 nuclei live for time τ1,

N2 nuclei live for time τ2, … and so on.

This quantity may be related with λ. Using calculus (vi) may be rewritten as:

τ¯=∫t |dN| ∫ |dN|

Where |dN| is the number of nuclei decaying between t, t+dt; the modulus sign is required to ensure that it is positive.

Where |dN| is the number of nuclei decaying between t, t + dt; the modulus sign is required to ensure that it is positive.

dN = −λN0 e−λt dt

|dN| = λN0 e−λt dt

∴ τ̄ = ∫0∞ tλN0 e−λt dt / ∫0∞ λN0 e−λt dt

= ∫0∞ t e−λt dt / ∫0∞ e−λt dt = 1/λ2 / 1/λ (integrating the numerator by parts)

or τ̄ = 1/λ

The Nucleus

It exists at the centre of an atom, containing entire positive charge and almost whole of mass. The electron revolve around the nucleus to form an atom. The nucleus consists of protons (+ve charge) and neutrons.

(i) A proton has positive charge equal in magnitude to that of an electron

(+1.6 x 10–19 C) and a mass equal to 1840 times that of an electron.

(ii) A neutron has no charge and mass is approximately equal to that of proton.

(iii) The number of protons in a nucleus of an atom is called as the atomic number (Z) of that atom. The number of protons plus neutrons (called as Nucleons) in a nucleus of an atom is called as mass number (A) of that atom.

(iv) A particular set of nucleons forming an atom is called as nuclide. It is represented as ZXA.

(v) The nuclides having same number of protons (Z), but different number of nucleons (A) are called as isotopes.

(vi) The nuclide having same number of nucleons (A), but different number of protons (Z) are called as isobars.

(vii) The nuclide having same number of neutrons (A - Z) are called as isotones.

MASS DEFECT & BINDING ENERGY

The nucleons are bound together in a nucleus and the energy has to be supplied in order to break apart the constituents into free nucleons. The energy with which nucleons are bounded together in a nucleus is called as Binding Energy (B.E.). In order to free nucleons from a bounded nucleus this much of energy (= B.E.) is to be supplied.

It is observed that the mass of a nucleus is always less than the mass of constituent (free) nucleons. This difference in mass is called as mass defect and is denoted as Dm.

If mn : mass of a neutron ; mp : mass of a proton

M (Z, A) : mass of bounded nucleus

Then, Dm = Z . mp + (A – Z). mn – M (Z, A)

This mass-defect is in form of energy and is responsible for binding the nucleons together. From Einstein's law of inter-conversion of mass into energy:

E = mc2 (c : speed of light; m : mass)

binding energy = Dm . c2

Generally, Dm is measured in amu units. So let us calculate the energy equivalent to 1 amu. It is calculated in eV (electron volts; 1 eV = 1.6 x 10–19 J)

Binding Energy Notes

1 amu = 1.67 × 10-27 (3×108) )2 1.6 × 10-19 eV ≈ 931 × 10⁶ eV = 931 MeV

∴ B.E. = Δm(931) MeV

There is another quantity which is very useful in predicting the stability of a nucleus called as Binding energy per nucleons.

B.E. per nucleons = Δm(931) A MeV

8.5 MeV

From the plot of B.E./nucleons Vs mass number (A), we observe that:

(i) B.E./nucleons increases on an average and reaches a maximum of about 8.7 MeV for A º 50 – 80.

(ii) For more heavy nuclei, B.E./nucleons decreases slowly as A increases. For the heaviest natural element U238 it drops to about 7.5 MeV.

(iii) From above observation, it follows that nuclei in the region of atomic masses 50-80 are most stable.

NUCLEAR FORCES

The protons and neutrons are held together by the strong attractive forces inside the nucleus. These forces are called as nuclear forces.

(i) Nuclear forces are short-ranged. They exist in small region (of diameter 10–15 m = 1 fm). The nuclear force between two nucleons decrease rapidly as the separation between them increases and becomes negligible at separation more than 10 fm.

(ii) Nuclear force are much stronger than electromagnetic force or gravitational attractive forces.

(iii) Nuclear force are independent of charge. The nuclear force between two proton is same as that between two neutrons or between a neutron and proton. This is known as charge independent character of nuclear forces.

In a typical nuclear reaction

(i) In nuclear reactions, sum of masses before reaction is greater than the sum of masses after the reaction. The difference in masses appears in form of energy following the Law of inter-conversion of mass & energy. The energy released in a nuclear reaction is called as Q Value of a reaction and is given as follows.

If difference in mass before and after the reaction is Dm amu

(Dm = mass of reactants minus mass of products)

then Q value = Dm (931) MeV

(ii) Law of conservation of momentum is also followed.

(iii) Total number of protons and neutrons should also remain same on both sides of a nuclear reaction.

NUCLEAR FISSION

The breaking of a heavy nucleus into two or more fragments of comparable masses, with the release of tremendous energy is called as nuclear fission. The most typical fission reaction occurs when slow moving neutrons strike 92U235. The following nuclear reaction takes place.

23592U + 10n → 14156Ba + 9236Kr + 3 10n + 200 MeV

If more than one of the neutrons produced in the above fission reaction are capable of inducing a fission reaction (provided U235 is available), then the number of fissions taking place at successive stages goes increasing at a very brisk rate and this generates a series of fissions. This is known as chain reaction. The chain reaction takes place only if the size of the fissionable material (U235) is greater than a certain size called the critical size.

If the number of fission in a given interval of time goes on increasing continuously, then a condition of explosion is created. In such cases, the chain reaction is known as uncontrolled chain reaction. This forms the basis of atomic bomb.

In a chain reaction, the fast moving neutrons are absorbed by certain substances known as moderators (like heavy water), then the number of fissions can be controlled and the chain reaction is such cases is known as controlled chain reaction. This forms the basis of a nuclear reactor.

NUCLEAR FUSION

The process in which two or more light nuclei are combined into a single nucleus with the release of tremendous amount of energy is called as nuclear fusion. Like a fission reaction, the sum of masses before the fusion (i.e. of light nuclei) is more than the sum of masses after the fusion (i.e. of bigger nucleus) and this difference appears as the fusion energy. The most typical fusion reaction is the fusion of two deuterium nuclei into helium.

11H + 21H → 42He + 21.6 MeV

For the fusion reaction to occur, the light nuclei are brought closer to each other (with a distance of 10–14 m). This is possible only at very high temperature to counter the repulsive force between nuclei. Due to this reason, the fusion reaction is very difficult to perform. The inner core of sun is at very high temperature, and is suitable for fusion, in fact the source of sun's and other star's energy is the nuclear fusion reaction